Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau) & Marie Thibault

Discover the remarkable journey of Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau) of Marsilly, Aunis, and Marie Thibault from the Angers region of France. Married in Québec in 1680, they built new lives at Saint-Thomas in Montmagny—founding a French-Canadian lineage that endures through generations of descendants.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau) & Marie Thibault

Founders of the Laurendeau Family in Canada

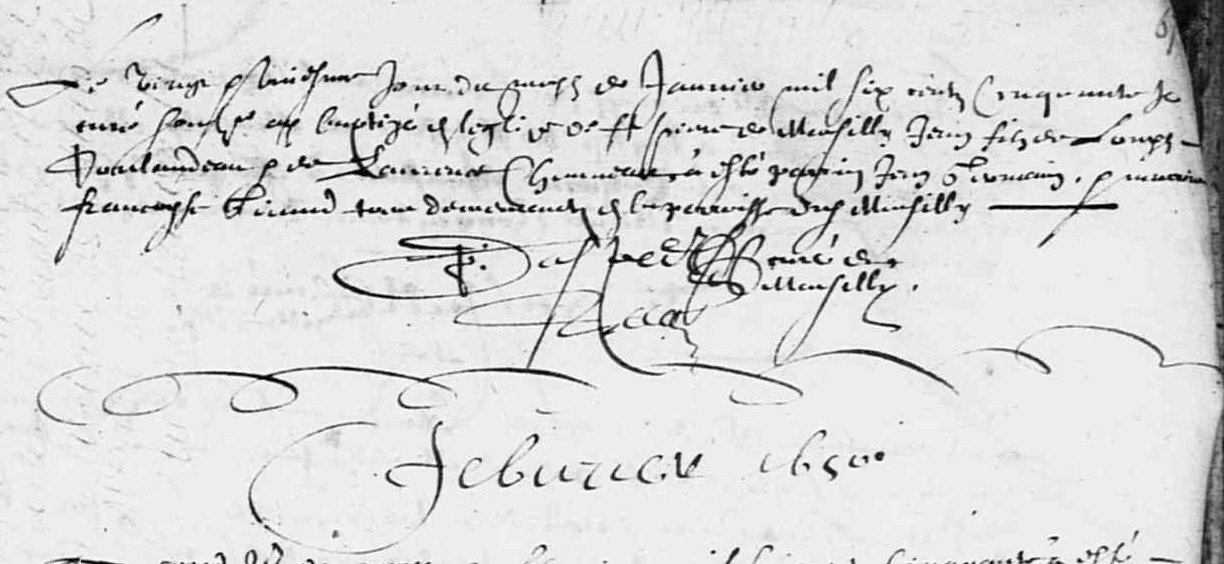

Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau), son of Louys Rolandeau and Laurence Chauveau, was baptized on January 21, 1650, in the parish of Saint-Pierre in Marsilly, Aunis, France. His godparents were Jean Germain and Françoise Giraud. Jean grew up alongside five siblings: Marie, Laurence, Jeanne, Marguerite and Hilaire.

1650 baptism of Jean Laurendeau (or Rolandeau) (Archives départementales de la Charente-Maritime)

The Church of Saint-Pierre in Marsilly—where Jean was baptized—was first mentioned in 1223. It originally formed part of a priory under the Abbey of Saint-Michel-en-l’Herm. Badly damaged during the early stages of the Hundred Years’ War, it was rebuilt and fortified between about 1360 and 1420, including the construction of a massive defensive clocher-porche (tower-porch) that still dominates the village. The church again suffered destruction in 1568 during the Wars of Religion, after which only the central nave was rebuilt (1608–1610). Later additions included the installation of the baptismal fonts in 1635, a sacristy in 1730 (enlarged in 1873), and major renovations to the nave and furnishings around 1849–1850. The surviving tower, classified as a historic monument in 1907, rises about 23 metres and offers sweeping views over La Rochelle and the Île de Ré—one of the finest surviving examples of a fortified coastal parish church in Aunis.

Church of Saint-Pierre in Marsilly (photo by Patrick Despoix, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Church of Saint-Pierre in Marsilly (photo by Patrick Despoix, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Located just four kilometres north of La Rochelle and facing Île-de-Ré, Marsilly lies in today’s department of Charente-Maritime and is considered a suburb of La Rochelle. The town has a population of about 3,000 residents, known as Marsellois and Marselloises.

Life in 17th-Century Marsilly

Location of Marsilly in France (Mapcarta)

Jean grew up in a coastal parish shaped by mixed farming, fishing, and salt production along the bays and islands of Aunis, notably around Île de Ré and the Baie de l’Aiguillon. Daily life revolved around cereal cultivation, livestock rearing, and coastal trades such as fishing and salt handling, all sustained by the bustling market of La Rochelle—then a regional hub for wine, salt, and Atlantic commerce.

The generation before Jean’s birth had endured the 1627–28 siege of La Rochelle and its aftermath. Although the city eventually fell and Huguenot political power was curtailed, Protestant communities survived under close royal control. Mid-century unrest during the Fronde (1648–53) brought further hardship, as civil strife and heavy taxation disrupted the region.

By the early 1670s, emigration to New France had become a familiar path for young men from Aunis. Hundreds signed contrats d’engagement in La Rochelle to work overseas for three-year terms as sailors, craftsmen, or farm labourers. Royal policy under Intendant Jean Talon encouraged settlement through land grants, employment in fisheries and river transport, and marriage incentives, making New France an attractive prospect for single men with rural or maritime skills. For many from Aunis, the promise of land ownership and social mobility offered opportunities unavailable at home.

Emigration to New France

Jean’s exact arrival date in New France is unknown. However, thanks to research by André Thibault, we know he was present in New France earlier than previously believed. A 1721 court case (Alarie vs. Letartre) concerning land in the seigneury of Dombourg (Neuville) mentions “a concession in the seigneury of Dombourg granted by Jean-François Bourdon, seigneur of Dombourg, to Jean Laurendeau, dated March 20, 1667.”

Seigneurie de Saint-Luc

In 1653, wheelwright Noël Morin was granted the arrière-fief of Saint-Luc—part of the seigneurie of Rivière-du-Sud (Montmagny)—by Jean de Lauson. Beginning in 1672, Morin divided the land and distributed it to his children and other settlers. [The modern Chemin Saint-Luc in Montmagny “crosses the southern part of the former arrière-fief Saint-Luc,” locating the fief roughly south of the Rivière du Sud within the present city limits.]

On April 7, 1676, Jean received a land concession in the seigneurie of Saint-Luc from seigneur Noël Morin de St-Luc. The land measured three arpents of frontage, facing the St. Lawrence, by forty arpents deep, adjoining the concessions of Jean Prou [Proulx] and Pierre Blanchet. Jean also received hunting and fishing rights on his concession. He agreed to pay six livres in seigneurial rente and twelve deniers in cens annually on the feast day of Saint Rémy and to maintain any roads crossing the land. The deed was drafted by notary Pierre Duquet de la Chesnaye in his office. Jean declared that he did not know how to sign.

Location of Montmagny in Québec (Mapcarta)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, November 2025

Marie Thibault

Marie Thibault, daughter of Michel Thibault and Jeanne Soyer, was born around 1661 in the Angers area of France, today part of the Maine-et-Loire department. Her baptism record has not been located. [Marie’s surname was spelled in a variety of phonetic ways in Canada: Thibaut, Thibaud, Thibot, etc.]

Marie emigrated from France with her parents, arriving in the mid-1660s. The Thibault family first settled in Sillery and later in Québec. Michel and Jeanne had five additional children born in Canada, four of whom married, and three of whom established families with descendants.

Marriage

On April 2, 1680, notary Gilles Rageot drafted a marriage contract between Jean “Rollandeau” and Marie “Thibaud.” Jean was described as an habitant residing in the seigneurie of Saint-Luc. Marie’s father, Michel, acted on her behalf. The witnesses were Nicolas Sarazin, Catherine Normand, Jeanne Delestre, Marie Magdeleine Morin, and Etiennette Normand. The contract followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. The prefix dower was set at 300 livres, and Marie’s father promised her a cow on the eve of her wedding day. Several witnesses signed the contract, but Jean and Marie could not.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children. The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him.

Jean and Marie married on April 24, 1680, in the church of Notre-Dame in Québec. He was 30 years old, originally from “the bourg and parish of Marsilley,” and a resident of the seigneurie of Saint-Luc. She was about 19 years old, living in the seigneurie de Maure with her parents. Their witnesses were Marie’s father, Jean Delastre [Delestre], Pierre Girard, and Pierre Jonqua [Joncas]. Neither the couple nor their witnesses could sign the marriage record.

1680 marriage of Jean "Rollandeau" and Marie Thibault (Généalogie Québec)

Life as an Habitant

In 1681, Jean and Marie appeared in the census of New France as residents of the seigneurie of Bellechasse, near Saint-François-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud. [There was no separate heading for the seigneurie of Saint-Luc in the census; the couple likely still lived there.] They owned two guns, one cow, and six arpents of “valuable” land—that is, land cleared or under cultivation.

1681 census of New France for the “Rollandeau” household (Library and Archives Canada)

Jean continued to clear and work his land. On July 17, 1684, he leased a five-year-old black-haired milk cow from Catherine Normand (who had witnessed his marriage contract), wife of master edge-tool maker Pierre Normand dit Labrière, for sixteen livres. [The duration of the lease is unclear.] Jean was described as a resident of the seigneurie of rivière Saint-Luc.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, November 2025

Jean and Marie later settled in the parish of Saint-Thomas in Montmagny. For reasons unknown, they did not have any children until sixteen years after their 1680 wedding:

Marie Anne (1696–1778)

Catherine (1698–1770) (twin)

Marie Louise Geneviève (1698–1781) (twin)

Marie Louise (1699–1772)

Louis Joseph (1701–1764)

Possible Explanations

The sixteen-year gap between the couple’s marriage and the birth of their first recorded child most likely reflects a period of subfertility or repeated pregnancy loss. Marie may have experienced miscarriages or stillbirths that went unrecorded, or difficulty conceiving during her twenties, with fertility returning later in life. The fact that she gave birth to twins near the end of her childbearing years aligns with the observed increase in dizygotic twinning among women in their mid- to late thirties.

It is also possible, though less likely, that earlier births simply went unrecorded or were lost from parish registers. Infant mortality was high in New France, and gaps in documentation occurred—especially for children who died before baptism or in remote settlements. However, the absence of any record of earlier children—no burials, marriages, or later references—makes this explanation less convincing than biological or health-related causes.

Available evidence suggests that Jean remained in the seigneurie during these years. There are no records of military service, fur-trade expeditions, or long absences from home, and the couple appear to have lived together continuously. He was likely occupied with clearing and farming his land, which makes a prolonged separation an improbable explanation for the delay in births.

On June 30, 1696, Jean sold a plot of land and habitation located at Rivière du Sud to Denis Prou [Proulx] for 275 livres. Jean was described as an habitant of Pointe à la Caille and parishioner of Saint-Thomas (Montmagny). The property measured five arpents of frontage on the St. Lawrence River by forty arpents deep. [It is unclear when Jean obtained this land, as the ownership details are left blank in this document—only that he received the concession from seigneur Couillard.] Prou agreed to assume the seigneurial cens et rente payments going forward.

Marie’s mother died in April 1699. On August 21, 1700, three of the Thibault daughters (Marie, Louise, and Marguerite) and their husbands agreed to sell their share in half a plot of land at Rivière des Roches, as well as their moveable property inherited from their mother, to their father Michel. He agreed to pay each couple 150 livres and 10 minots of wheat. [A minot was a measure once used for dry matter (seeds and flour) and which contained half of a mine. A mine corresponded to approximately 78.73 litres.]

Deaths of Marie and Jean

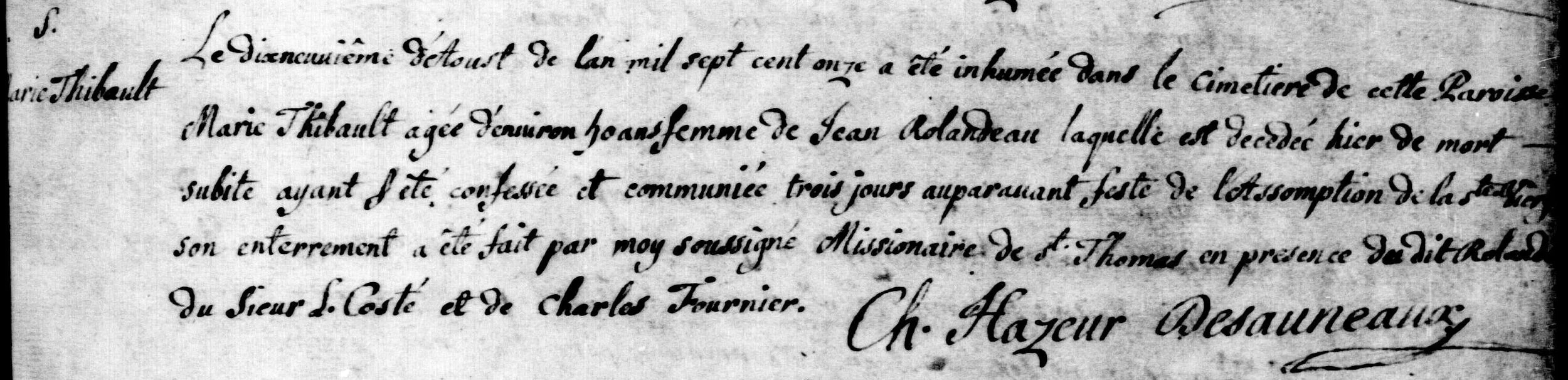

Marie Thibault “died suddenly” at about 50 years of age on August 18, 1711, “having confessed and received communion three days earlier on the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.” She was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Thomas in Montmagny. Her husband attended the burial.

1711 burial of Marie Thibault (Généalogie Québec)

Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau) died at the age of 65, “after receiving the sacraments of Viaticum and Extreme Unction.” He was buried on February 2, 1715, in the parish cemetery of Saint-Thomas in Montmagny. [The date of death was omitted from the burial record.]

1715 burial of Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau) (Généalogie Québec)

Succession

On the morning of October 2, 1717, the Rolandeau/Laurendeau children met with notary Abel Michel to determine guardianship arrangements and finalize their inheritance.

As was customary, a legal guardian was elected for the minor Rolandeau/Laurendeau children, Marie Louise and Louis Joseph. Charles and Pierre Fournier were chosen as tuteur (guardian) and subrogé tuteur (substitute guardian).

Once Jean and Marie’s inventory of goods was drawn up, the children divided the household furnishings, livestock, and land concession into five equal parts.

Guardianship in New France

Under the Coutume de Paris (the law in force in Canada), a tuteur (guardian) had to be appointed whenever a minor stood to receive or protect property. Because the Custom required equal partition among children, a tutelle (guardianship) was opened upon a parent’s death to manage a minor’s share until majority (usually age 25) or emancipation by marriage or court order. With early parental deaths common, guardianships were routine.

The appointment generally favoured the surviving spouse as guardian, chosen with the advice of a family council—often seven close relatives and family friends convened under a judge’s supervision. The judge intervened only in cases of dispute or refusal to serve. The Custom also provided for a subrogé tuteur (substitute guardian) selected from family or close friends to safeguard the minors’ interests and verify the inventory of community property.

Household Inventory

The six-page inventory itemized all of Jean and Marie’s possessions. Though some items are illegible, the list includes the following:

Page 3 of the 1717 inventory (FamilySearch)

Page 5 of the 1717 inventory (FamilySearch)

Kitchen utensils and tableware:

Four hooks serving as a trammel

One ladle

Two cooking pots

One red copper kettle

Three fireplace irons, two of them old

One grill

One pan

One pewter basin

One pewter plate

One earthenware dish

Nine pewter spoons

One dozen earthenware bowls

One earthenware oil jug

Another jug

One earthenware jug

Tools and weapons:

Two axes

One broken axe

Three pickaxes, one of them old

Seven sickles

One chisel

Two hammers and a pair of pliers

One bucket

One musket with its powder horn

Two razors with a sharpening stone

One clothes iron

One drag chain

One sledge

One pair of horseshoes

Bedding, furniture, and household items:

One feather bed with bolster

One feather bed covered in leather

Another larger bed covered in leather with bolster

Two old wool blankets

Two other blankets, one of them old

One candlestick

Two equipped spinning wheels

Two chests

Provisions and foodstuffs:

58 pounds of butter

One small butter tub containing 28 pounds of butter

Livestock and farm equipment:

Five red and black cows

Seven sheep

Four large pigs

Two small pigs

One mare

Two horses with collar, back strap, and bridle

Two foals

One rooster

One dozen poultry

Old scrap iron

Two flax brakes

Ten pounds of thread

Harvest and items in the barn:

600 sheaves of wheat

40 bundles of flax

One sledgehammer kept at the blacksmith’s

The inventory also recorded a total of 428 livres in debt, of which 300 livres was owed to Jean and Marie’s son-in-law, Jean Marotte.

The Lasting Heritage of the Laurendeau Family

Jean Rolandeau (or Laurendeau) and Marie Thibault stand at the foundation of the Laurendeau family in Canada. From their marriage in Québec in 1680 to their establishment in Montmagny, their lives reflect the experience of the first settlers who shaped New France through perseverance and hard work. The records they left—land concessions, contracts, censuses, and inventories—preserve the outline of a family whose legacy endures through generations of descendants rooted in Québec and beyond.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Marsilly > Collection communale > Baptêmes Mariages Sépultures > 1631 – 1676," database and digital images, Archives départementales de la Charente-Maritime (http://www.archinoe.net/v2/ark:/18812/781f08074ff121b345c6e8296368ea71 : accessed 7 Nov 2025), baptism of Jean Raulendeau, 21 Jan 1650, Marsilly (St-Pierre), image 62 of 236.

"L’Église Saint-Pierre," Mairie de Marsilly (https://www.marsilly.fr/notre-village/patrimoine/leglise-saint-pierre/ : accessed 7 Nov 2025).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/67219 : accessed 7 Nov 2025), marriage of Jean Rollandeau and Marie Thibaud, 24 Apr 1680, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/26411 : accessed 7 Nov 2025), burial of Marie Thibault, 19 Aug 1711, Montmagny (St-Thomas).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/26459 : accessed 7 Nov 2025), burial of Jean Rolandeau, 2 Feb 1715, Montmagny (St-Thomas).

"Actes de notaire, 1663-1687 // Pierre Duquet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-Y9HZ-G?cat=koha%3A1175224&i=2394&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), land concession to Jean Rollandeau from Noël Morin de St-Luc, 7 Apr 1676, images 2395-2396 of 2541 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-J3DQ-JW65?cat=koha%3A1171570&i=2323&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), marriage contract between Jean Rollandeau and Marie Thibaud, 2 Apr 1680, images 2324-2325 of 3381; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NF-494Z-2?cat=koha%3A1171570&i=542&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), lease of a cow by Jean Rollandeau from Catherine Normand, 17 Jul 1684, images 543-544 of 1327; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1695-1702 // Charles Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NX-43WF?cat=koha%3A963362&i=1285&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), land sale by Jean Rollandeau to Denis Prou, 30 Jun 1696, images 1286-1288 of 3357; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3NF-4SQ7-J?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=2078&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), agreement and sale of rights to movable property and half of a plot of land by Jean Rollandeau and Marie Tibault (and two of her sisters) to Michel Thibault., 21 Aug 1700, images 2079-2081 of 3419; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1749 // Abel Michon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LD-V99Z-R?cat=koha%3A979090&i=550&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), guardianship of the minor of Jean Rollandeau and Marie Tibault, 2 Oct 1717, image 551 of 2196; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1749 // Abel Michon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LD-V99C-G?cat=koha%3A979090&i=551&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), succession of Jean Rollandeau and Marie Tibault, 2 Oct 1717, images 552-553 of 2196; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1749 // Abel Michon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-R3LD-V9QN-L?cat=koha%3A979090&i=554&lang=en : accessed 7 Nov 2025), inventory of the community of goods of Jean Laurendeau and Marie Thibault, 2 Oct 1717, images 555-560 of 2196; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 7 Nov 2025), household of Jean Rollandeau, 14 Nov 1681, seigneurie de Bellechasse, page 232 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/laurendeau/-rolandeau : accessed 7 Nov 2025), entry for Jean Laurendeau/Rolandeau (person #242332), updated on 1 Sep 2019.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/4969 : accessed 7 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Jean LAURENDEAU and Marie THIBAULT, union 4969.

Louise Authier and Jean Laurendeau, Histoire et généalogie des Laurendeau d'Amérique et de leurs familles alliées sous le Régime français (https://www.jean-laurendeau.com/010_01_0150_pasameric.html : accessed 9 Nov 2025).

"Noël Morin," Répertoire du patrimoine du Québec, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, Gouvernement du Québec (https://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/rpcq/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=24732&type=pge : accessed 7 Nov 2025).

"Chemin Saint-Luc," Commission de toponymie, Gouvernement du Québec (https://toponymie.gouv.qc.ca/ct/ToposWeb/Fiche.aspx?no_seq=168317 : accessed 7 Nov 2025).

Jean-Philippe Garneau, "La tutelle des enfants mineurs au Bas-Canada : autorité domestique, traditions juridiques et masculinités," Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, volume 74, number 4, spring 2021, p. 11–35, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/1081966ar).