Edge-tool maker

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Le taillandier | The Edge-Tool Maker

The edge-tool maker (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, June 2025)

The taillandier specialized in making and repairing cutting tools, formerly known as taillants. In New France, this trade played an essential role in daily life. In a colonial society still heavily engaged in clearing land, the demand for axes, picks, ploughshares, and other iron tools was vital to agriculture, construction, and domestic life. The edge-tool maker, sometimes referred to as a forgeron-outilleur (toolsmith), was one of the most indispensable craftsmen in the colony.

Skilled ironworkers were few and far between in New France, which made the edge-tool maker’s role all the more crucial. Without him, settlers couldn’t effectively clear land or bring in abundant harvests. He supplied them with the agricultural tools needed for ploughing, sowing, and harvesting, as well as the iron fittings essential for building homes and forts. Because the colony was still sparsely populated, one craftsman often had to perform several trades. It wasn’t uncommon for a village blacksmith to also act as an edge-tool maker, locksmith, or gunsmith, depending on local demand. This kind of versatility—less common in metropolitan France, where trades were more specialized—reflected the economic realities of colonial life. As one historian observed, “in the Montréal area, before the mid-18th century, ironworkers practised all the metal trades at once.” In other words, the edge-tool maker in New France was part toolmaker, part farrier, and sometimes even a nailmaker or locksmith, especially in remote communities.

The edge-tool maker belonged to the category of free artisans—there was no strict guild system in the colony. His status was that of a skilled but modest tradesman, essential to the community but not part of the colonial elite. Many edge-tool makers were also habitants, farming the land alongside their craft to support themselves and their families.

Edge-tool making was one of the seven principal metalworking trades in New France, along with locksmithing, blacksmithing, tinsmithing, gunsmithing, coppersmithing, and the work of the arquebusier.

Tools Produced

At the heart of the edge-tool maker’s craft was the production and repair of any sharp-edged metal tool useful to settlers. His priority was agricultural implements for ploughing and maintaining the land—ploughshares, spades, shovels, hoes, axes, saws, and more. The list below outlines some of the key tools made by the edge-tool maker, along with their uses:

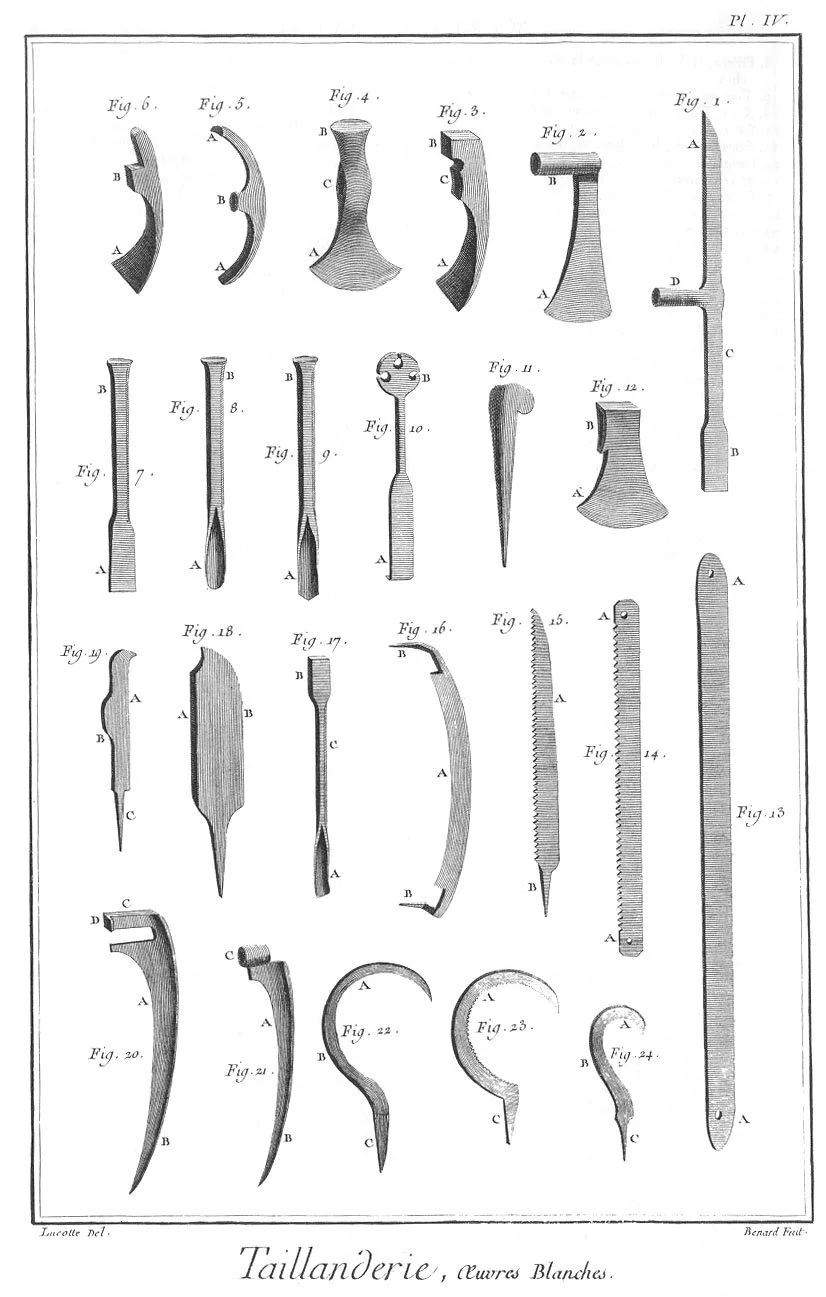

Axes and broadaxes – felling trees, cutting timber for construction

Scythes and sickles – harvesting grain and hay

Hoes and mattocks – breaking and clearing soil

Spades and shovels – light tilling, digging earth

Ploughshares and coulters – deep ploughing with animal-drawn ploughs

Knives, cleavers, and billhooks – for butchering, cooking, and general cutting tasks

An Edge-Tool Maker’s Workshop ("Le taillandier = Der Zeugschmied," 1847 drawing or painting by Jean Frédéric Wentzel, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

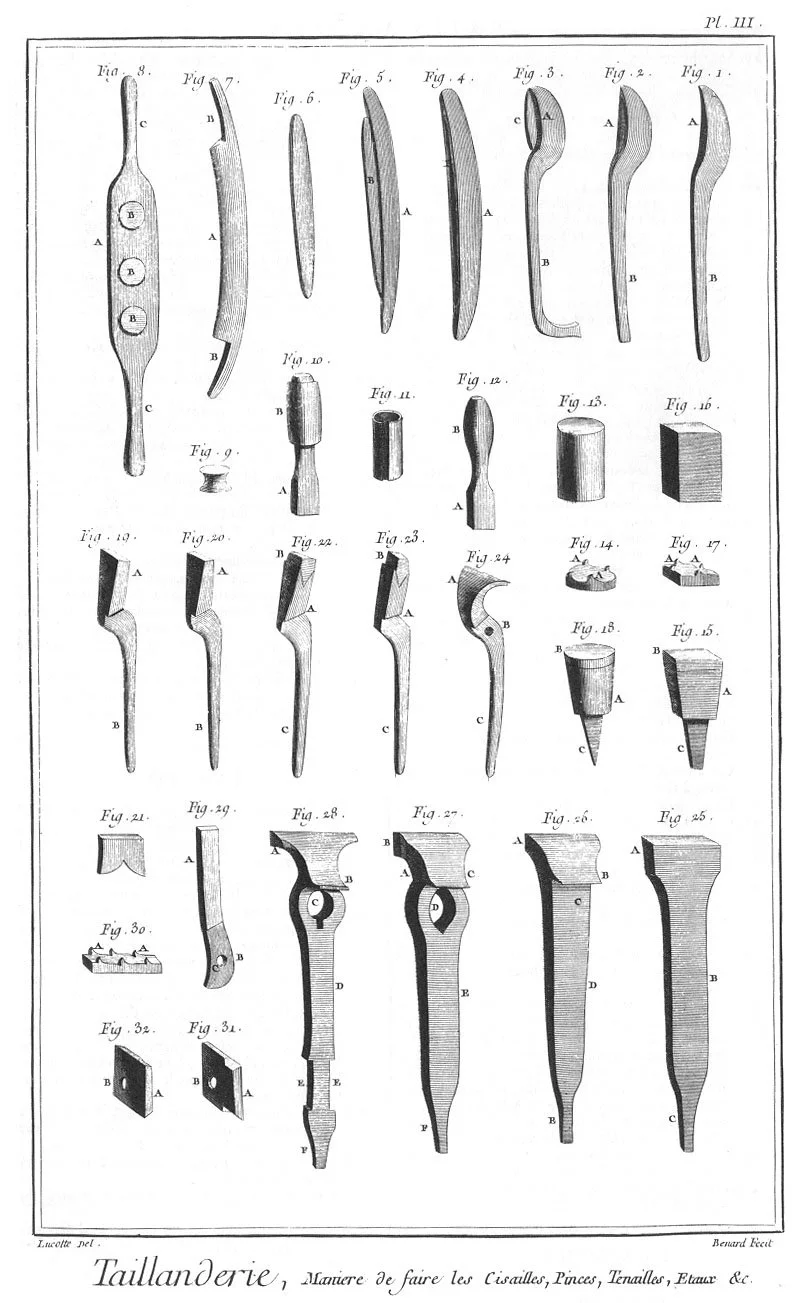

In addition to sharp-edged tools, many edge-tool makers had a broader skill set and produced other practical iron goods. These might include tinplate lanterns, moulds, files, and metal kitchen utensils such as fire tongs (pincettes) or roasting spits.

Some edge-tool makers were also capable of repairing or crafting larger items like hammers, weights (pesons), or iron fittings for carts and wagons.

“Ruling ordering Sieur Damours to pay Antoine Gaillou, edge-tool maker, the sum of 8 livres for a shovel and fire tongs he supplied to the Council,” January 21, 1665 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

“Ruling ordering Sieur de la Mothe to pay the sum of 250 livres to Pierre Sommandre, edge-tool maker, for the ironwork on the royal galley,” May 29, 1665 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Workshop and Craft Process

Advertisement in Le Spectateur canadien, January 14, 1829 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

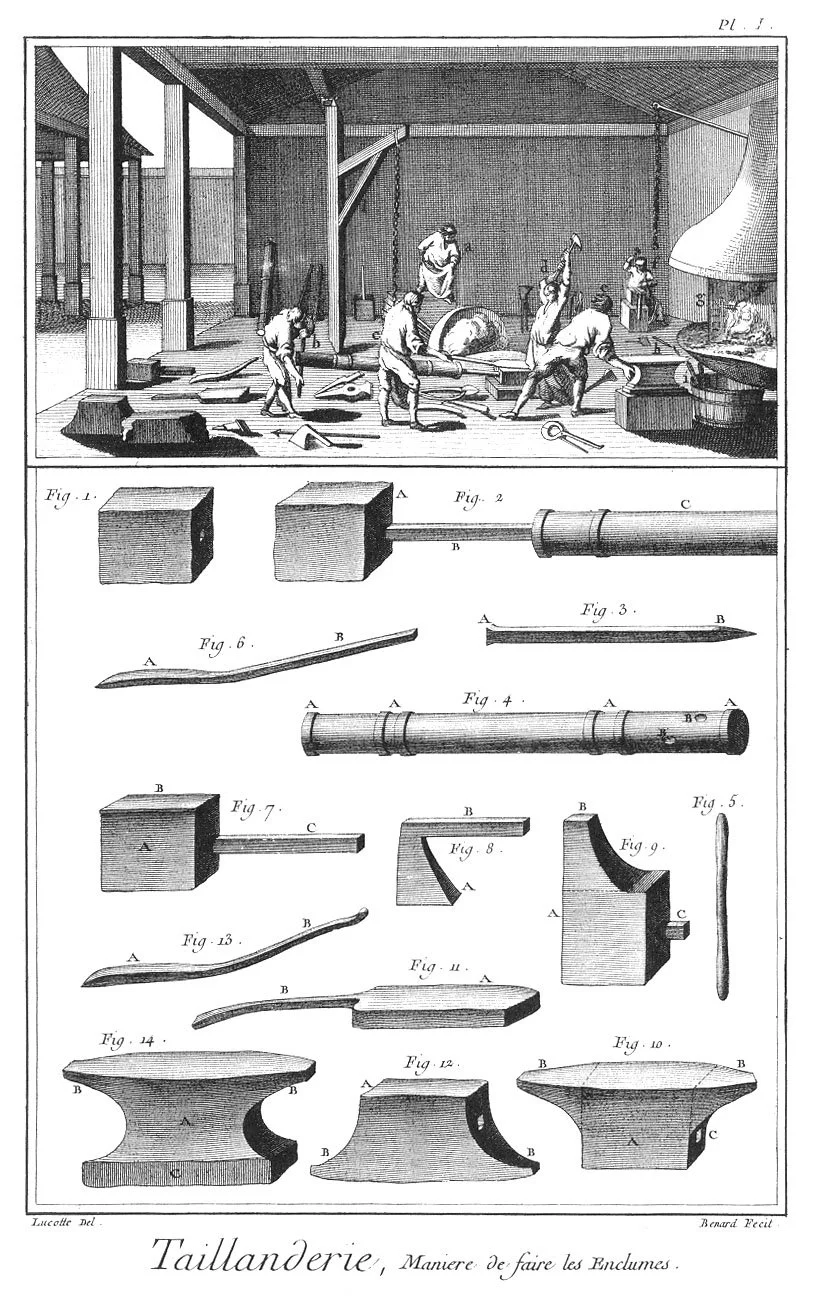

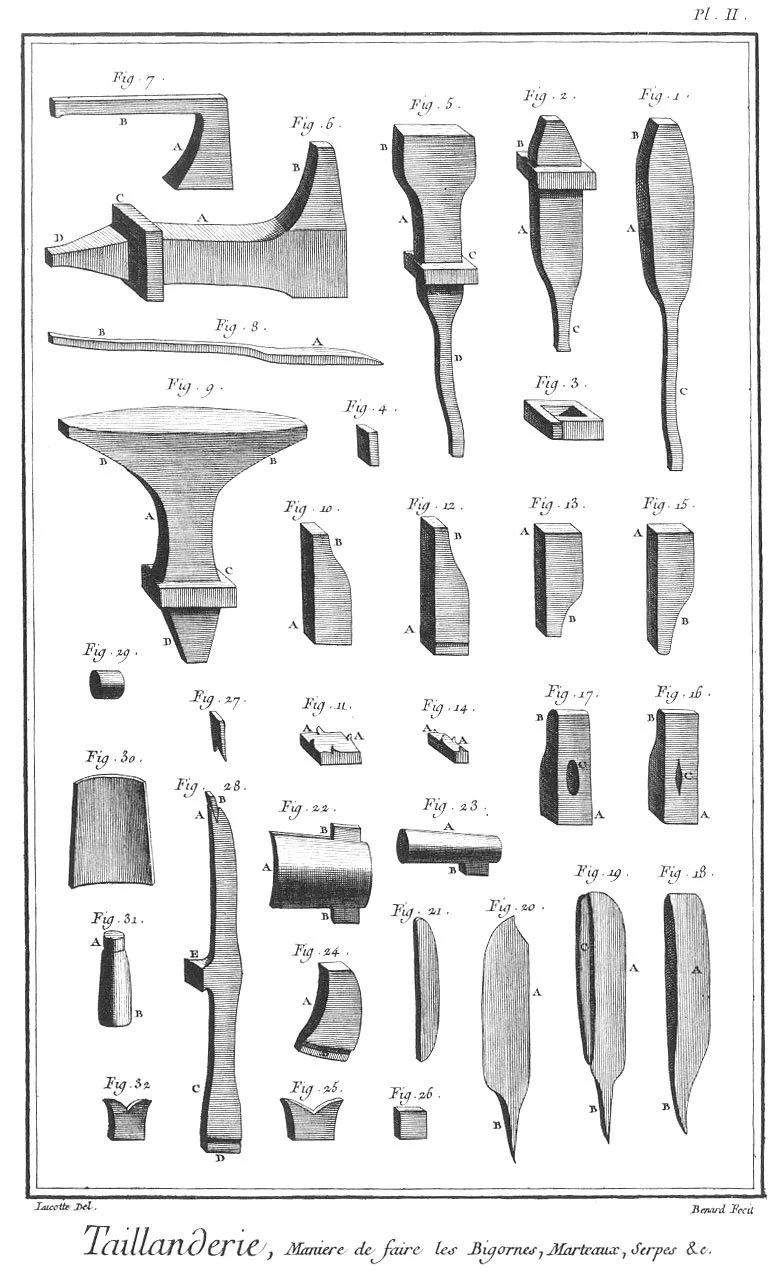

The edge-tool maker worked in a traditional forge much like that of other blacksmiths. His workshop featured a charcoal-fired hearth, kept hot by a bellows, and an anvil secured to a sturdy wooden block. Surrounding him were his tools: large forging hammers and tongs for handling red-hot iron, smaller hammers, chisels, and punches for detail work, and often one or more grindstones for sharpening.

The manufacturing process had changed little since the Middle Ages. The edge-tool maker heated a bar of iron or steel in the fire until it glowed red and became malleable, then shaped it with hammer blows on the anvil. For cutting tools, he would refine the blade edge and then apply heat treatment: quenching—plunging the heated piece into water or oil to harden the metal—followed by tempering, a gentler reheating that reduced brittleness by slightly softening the steel. This forge–quench–sharpen cycle was essential to create tools that were hard, sharp, and durable.

The colonial edge-tool maker relied primarily on iron and steel imported from France. It wasn’t until the 1730s, with the establishment of the Forges du Saint-Maurice near Trois-Rivières, that the colony gained a local source of iron and cast metal. These forges produced bar iron and moulded parts, supplying edge-tool makers and blacksmiths in Canada with essential raw materials. Wood was also indispensable—not only as fuel for the forge but also for crafting tool handles, typically made from ash, walnut, or elm.

Forges du Saint-Maurice (artist unknown, Wikimedia Commons)

A portion of a map of the Forges du Saint-Maurice (created by Joseph-Pierre Bureau in 1845, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Known Edge-Tool Makers: Louis Badayac dit Laplante, Urbain Beaudry dit Lamarche, François Bibeau, Jean Bizet, Charles Bonnier, René Bouchard dit Lavallée, Pierre Bouvier, Laurent Bransard dit Langevin, Charles Brousseau, Jean Buisson dit le Provençal, Étienne Campeau, Jacques Campeau, Jean Charon/Charron dit Laferrière, Jacques Chauvin, Jean Coitou dit St-Jean, André Corbin, Henri Crête, Jean Baptiste Demers, Denis Derome dit Descarreaux, Jean Drapeau dit Laforge, Jean Dubois, Guillaume Dupont, Jean Baptiste Dupré, Daniel Feys, Jean Filion, Pierre Foureur dit Champagne, Nicolas François, Antoine Gaillou, Augustin Gaulin, François Gauthier dit Larouche, Jean Gauthier dit Larouche, Jacques Genest dit Labarre, Pierre Genest, Nicolas Geoffroy, Augustin Gilbert, Antoine Girard, Jacques Girard dit Girardin, Jean Grès, Jacques Hédouin, Étienne Houde/Houle, Louis Jean dit Denis, Vital Joly, Pierre Juneau, Noël Lebrun/Brun dit Carrière, César Léger, Charles Legris, Joseph Lemire, Claude Martin, Michel Massé, Jean Milot dit le Bourguignon, Michel Morin, Jean Baptiste Normand, Louis Normand dit Brière/Labrière, Pierre Normand dit Brière/Labrière, Guillaume Pagé, Joseph Parent, Nicolas Périllard dit Bourguignon, Michel Pierre dit Desforges, Pierre Pivin, Michel Poirier dit Langevin, Jean Pothier dit Laverdure, Toussaint Pothier dit Laverdure, Henri Rémi Picoron dit Descoteaux, Claude Rancourt, François Robin, Charles Robitaille, Pierre Roussel, Abel Sagot dit Laforge, Pierre Sommandre [Soumande], Jean Baptiste Toupin, Pierre Toupin, Barthélémy Verreau dit le Bourguignon, François Vildary.

Known Master Edge-Tool Makers: Urbain Beaudry dit Lamarche, Jean Boucher, Antoine Bouton, Pierre Bouvet, Charles Brousseau, Étienne Campeau, Jean Baptiste Chamard, Jean Coitou dit St-Jean, André Corbin, Henri Crête, Louis Cureux dit St-Germain, Jean Baptiste Demers, Denis Derome dit Descarreaux, Pierre Dubreuil, Jean Baptiste Dupras, Jean Filion, François Gauthier, Nicolas Geoffroy, Augustin Gilbert, Antoine Girard, Jacques Girard, Mathurin Guillemet, Louis Jean dit Denis, François Jobin, Pierre Juneau, Jean Baptiste Langevin dit Bronsard, Pierre Mailloux, Gabriel Maranda, Claude Martin, Michel Morin, Guillaume Pagé, Joseph Parent, Louis Parent, Michel Poirier dit Langevin, Claude Rancourt, Abel Sagot dit Laforge, Pierre Sommandre [Soumande], René Toupin, Jean Baptiste Trudeau.

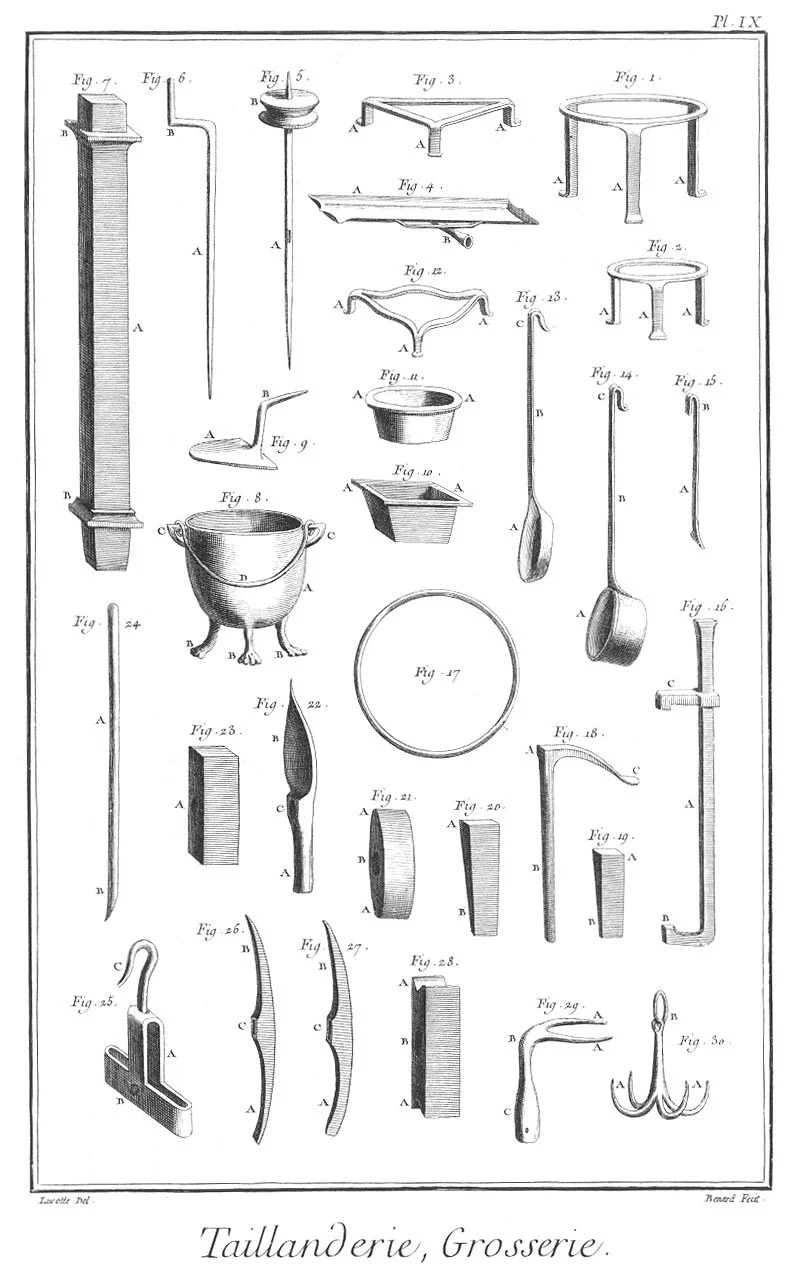

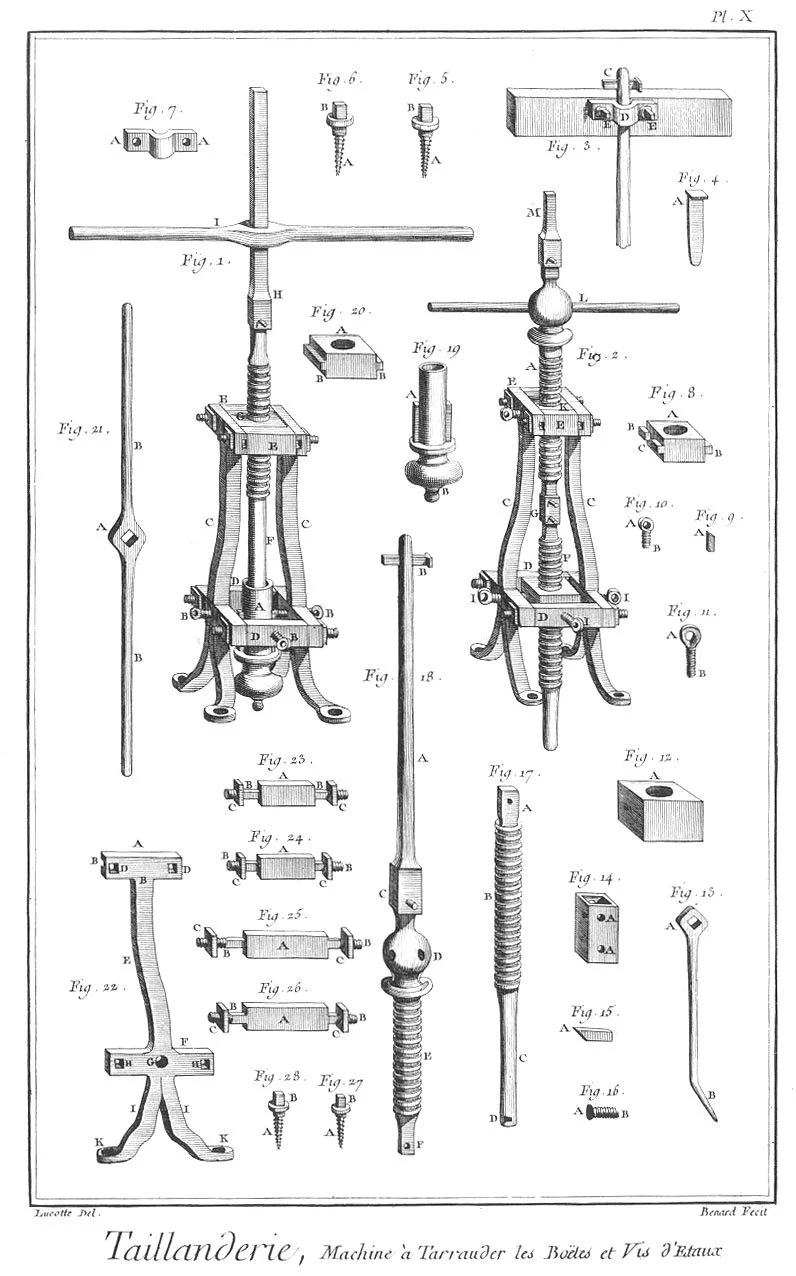

The French Edge-Tool Maker

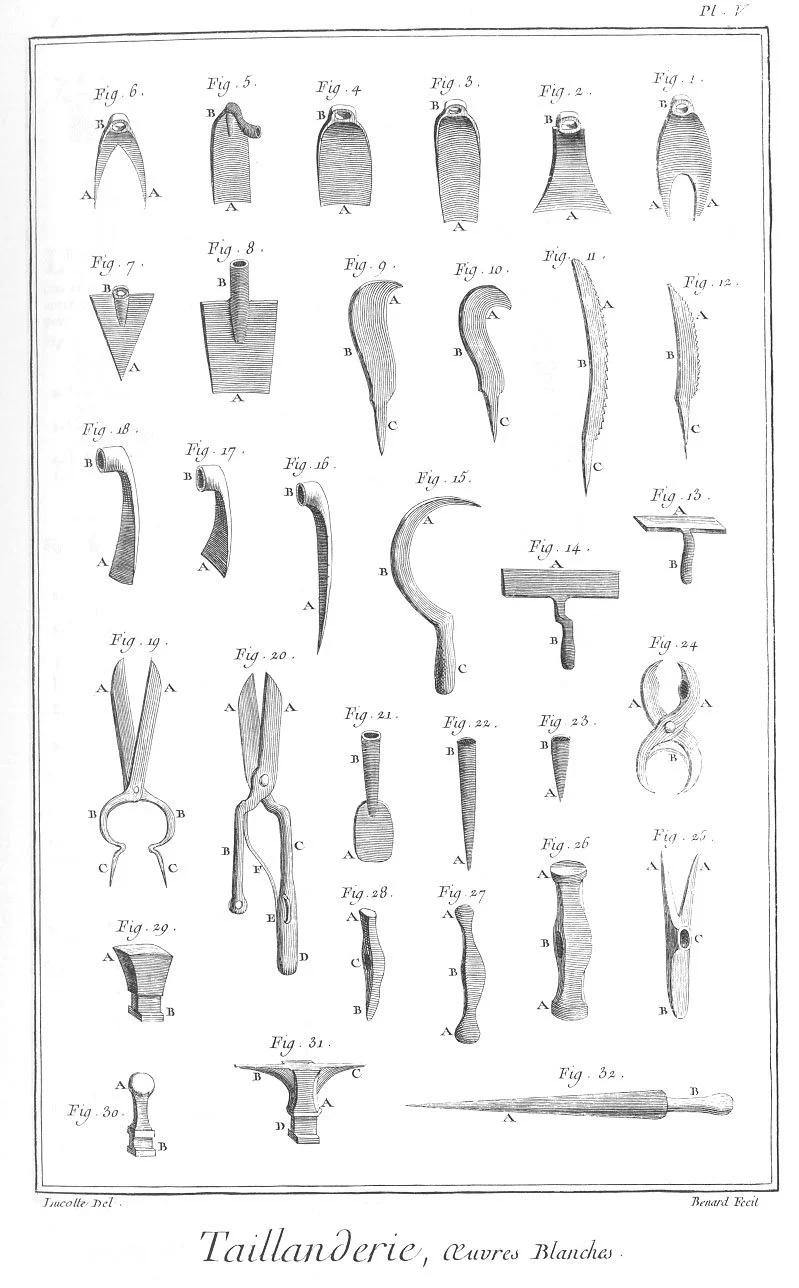

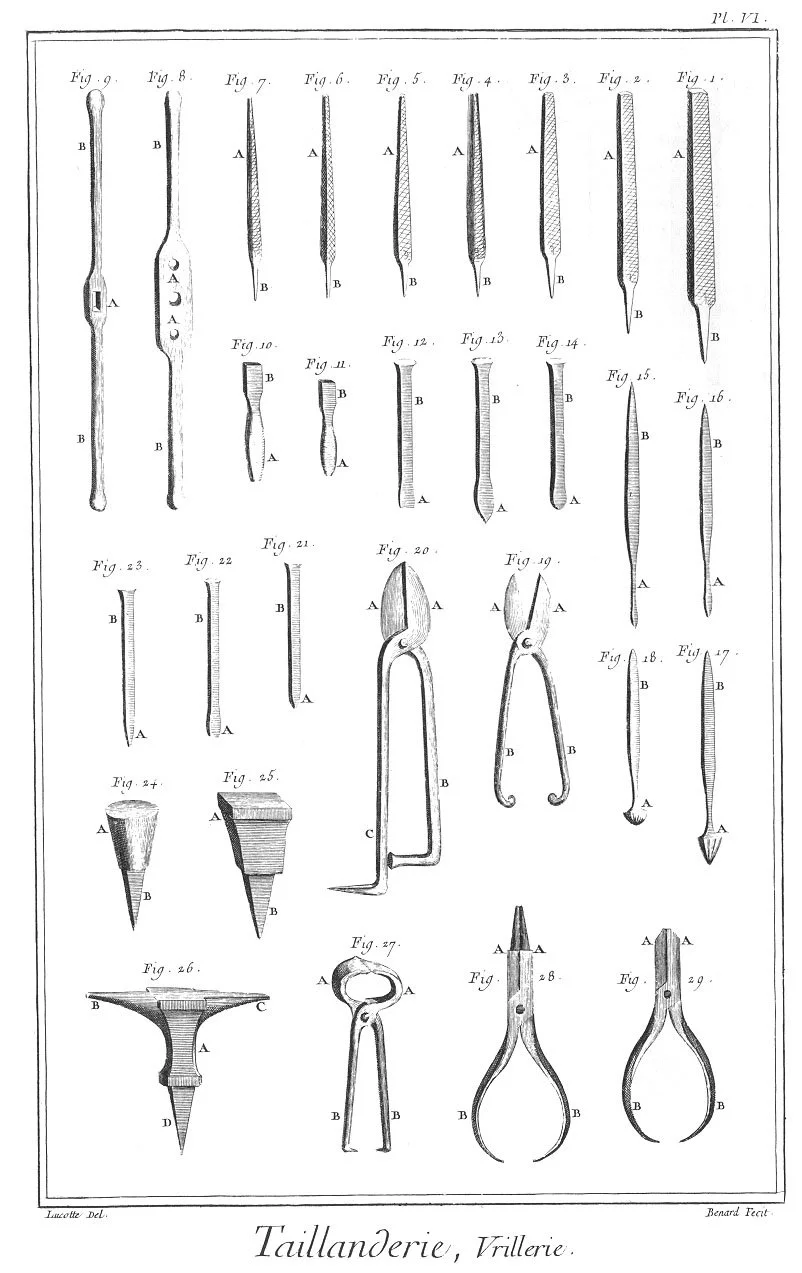

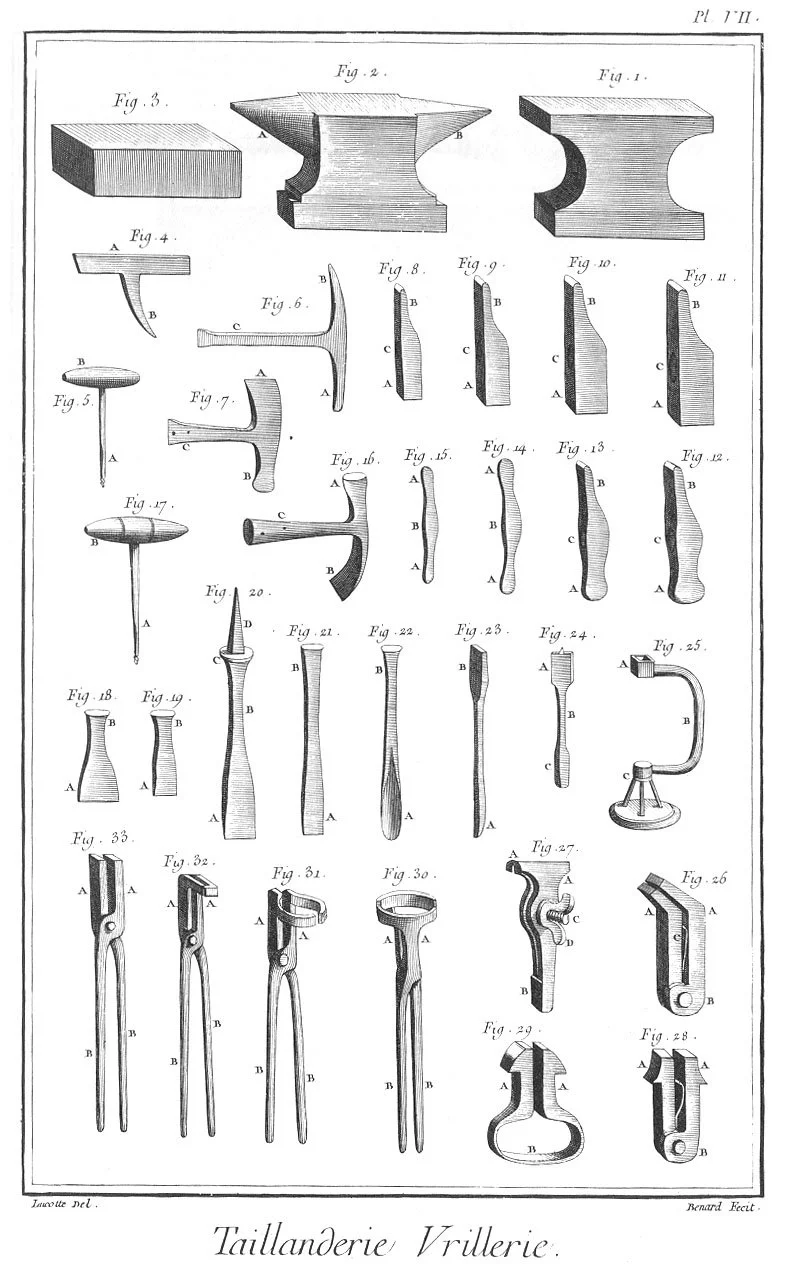

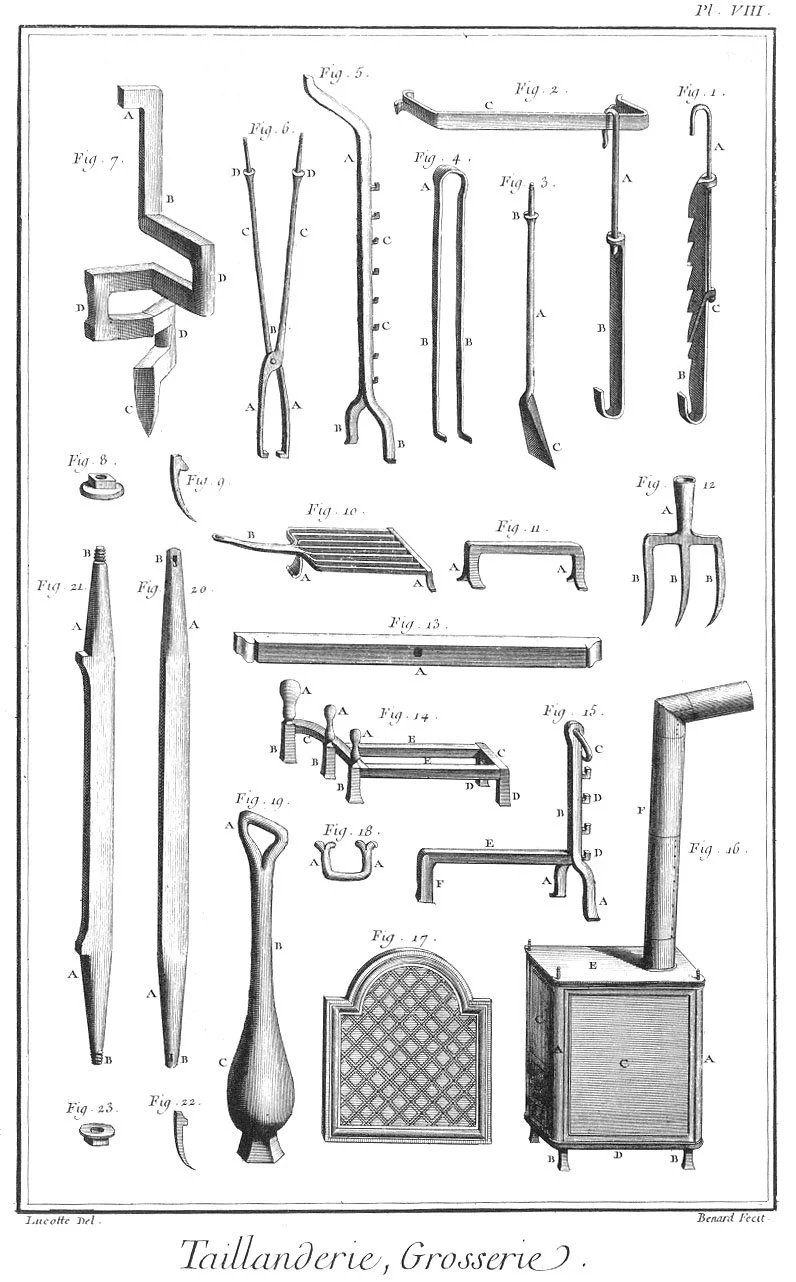

In France, the trade of edge-tool maker took shape in the Middle Ages through craft guilds. Specializing in the production of cutting tools, the taillandier was a highly respected artisan, trained through a lengthy apprenticeship and bound by strict regulations to earn his title. The trade thrived until the 18th century, as evidenced by Diderot’s Encyclopédie, which includes several illustrated plates dedicated to the profession. At the time, French workshops were often larger and better equipped than those in New France, though the forging techniques remained fundamentally manual.

"Taillanderie," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (University of Michigan Library)

Starting in the 19th century, the trade went into rapid decline with the rise of industrial edge-tool manufacturing. Traditional workshops gradually gave way to mechanized factories, particularly in eastern France (Franche-Comté, Jura). The mechanization of agriculture further hastened the disappearance of the traditional craft. Today, only a handful of artisan blacksmiths preserve this knowledge, mainly for heritage or artistic purposes.

Edge-Tool Making and the Restoration of Notre‑Dame de Paris

One such initiative is La Maison Luquet, which aims to safeguard the future of edge-tool making by reimagining the role of the forge in the 21st-century economy—reconnecting it with other manual trades and traditional crafts. The company played a key role in the restoration of Notre‑Dame de Paris: it was selected by the carpentry firms charged with manually shaping the medieval roof trusses of the nave and choir. Working in collaboration with partner edge-tool makers, they forged around sixty traditional axes used by the carpenters to hand‑hewn the 1,200 oak beams required to rebuild the cathedral’s roof structure.

In Montreal, Les Forges de Montréal—a non‑profit organization dedicated to preserving traditional edge‑tool blacksmithing—also played a vital role in the restoration of Notre‑Dame de Paris. Under the leadership of master blacksmith and edge-tool maker Mathieu Collette, the workshop forged sixty historically accurate axes over four months, providing carpenters with the precise tools needed to recreate the original 13th‑century wood‑marks on the cathedral’s oak roof frame.

As Collette explains: “We know what the tools looked like at that time and in that region… but if you don’t have a blacksmith capable of making those tools, the carpenter won’t be able to leave the right marks.” His work ensures that both the techniques and the tool marks left on the wood remain historically authentic.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Dominique Bouchard, “Structure et effectifs des métiers du fer à Montréal avant 1765 ,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, 1995, 49(1), pp. 73–85, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/305400ar : accessed 31 Jul 2025).

Isabelle Lazier and Nicole Barthélémy, “Les taillandiers de la Fure,” Terrain, no. 6, 1986, posted online 24 July 2007, digitized by OpenEdition Journals (http://journals.openedition.org/terrain/2895 : accessed 9 Jul 2025).

Claude Lemay, “Fonctions et métiers délaissés,” L’Ancêtre, no. 281, vol. 34, Winter 2008, and no. 280, vol. 34, Winter 2007.

Robert Pistre, “Un métier perdu de vue : Les taillandiers ,” La gazette des amoureux des Monts de Lacaune (https://gazettelacaune.fr/2024/05/21/un-metier-perdu-de-vue-les-taillandiers/ : accessed 31 Jul 2025).

“Edge-Tool Maker,” digitized plates, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 9 (plates) (Paris, 1765), digitized by the University of Michigan Library (http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0001.611 : accessed 9 Jul 2025).

“Arrêt qui ordonne au sieur Damours de payer à Antoine Gaillou, taillandier, la somme de 8 livres pour une pelle et pincette à feu qu'il a fournies au Conseil ,” digitized images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/399592 : accessed 9 Jul 2025, 21 Jan 1665, reference TP1,S28,P296, ID 399592.

“Arrêt qui ordonne au sieur de la Mothe de payer à la somme de 250 livres à Pierre Sommandre, taillandier pour les ferrures de la galiote royale (galère),” digitized images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/399925 : accessed 9 Jul 2025), 29 May 1665, reference TP1,S28,P403, ID 399925.