Mathurin Palin (or Pallain) dit D’Abonville & Louise Renaud

Discover the life of Mathurin Palin (or Pallain) dit D’Abonville and his wife Louise Renaud, pioneers of early Québec. A sailor turned river captain, Mathurin built his life and family along the St. Lawrence River, shaping generations of descendants in New France.

Mathurin Palin (or Pallain) dit D’Abonville & Louise Renaud

From Sailor to River Captain: A Life on the St. Lawrence

Mathurin Palin (or Pallain) dit D’Abonville, son of Pierre Pallain and Florence Maxias (or Matias), was born around 1663 in the parish of Sainte-Radegonde in Poitiers, Poitou, France. Located in central western France, Poitiers is the capital (prefecture) of the Vienne department today. It has approximately 90,000 residents, called Poitevins and Poitevines.

Ascendance in France

Several more generations of Mathurin’s family in France are documented. His parents signed their marriage contract before notary Touton on July 4, 1655. He had at least seven siblings, all baptized in the parish of Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Poitiers: Catherine, Denise, Charles, Madeleine, Catherine, Françoise, and Joseph.

Mathurin’s mother, Florence, was baptized on February 1, 1626, in the parish of Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Poitiers. Her parents were François Maxias (or Matias), a merchant and bootmaker, and Françoise Jousselin.

1626 baptism of Florence Matias (Archives départementales des Deux-Sèvres et de la Vienne)

Mathurin’s paternal grandparents were Jehan Pallain, a pewterer and merchant in the faubourg of Montbernage in Poitiers, and Jacquette Fergeault, who signed their marriage contract on January 21, 1629, before notary Pommeraye in Poitiers. Jehan’s parents were Mathurin Pallain, a fuller and cloth merchant, and Perrine Delanouzière. Jacquette’s parents were Daniel Fergeault and Anne Muraille.

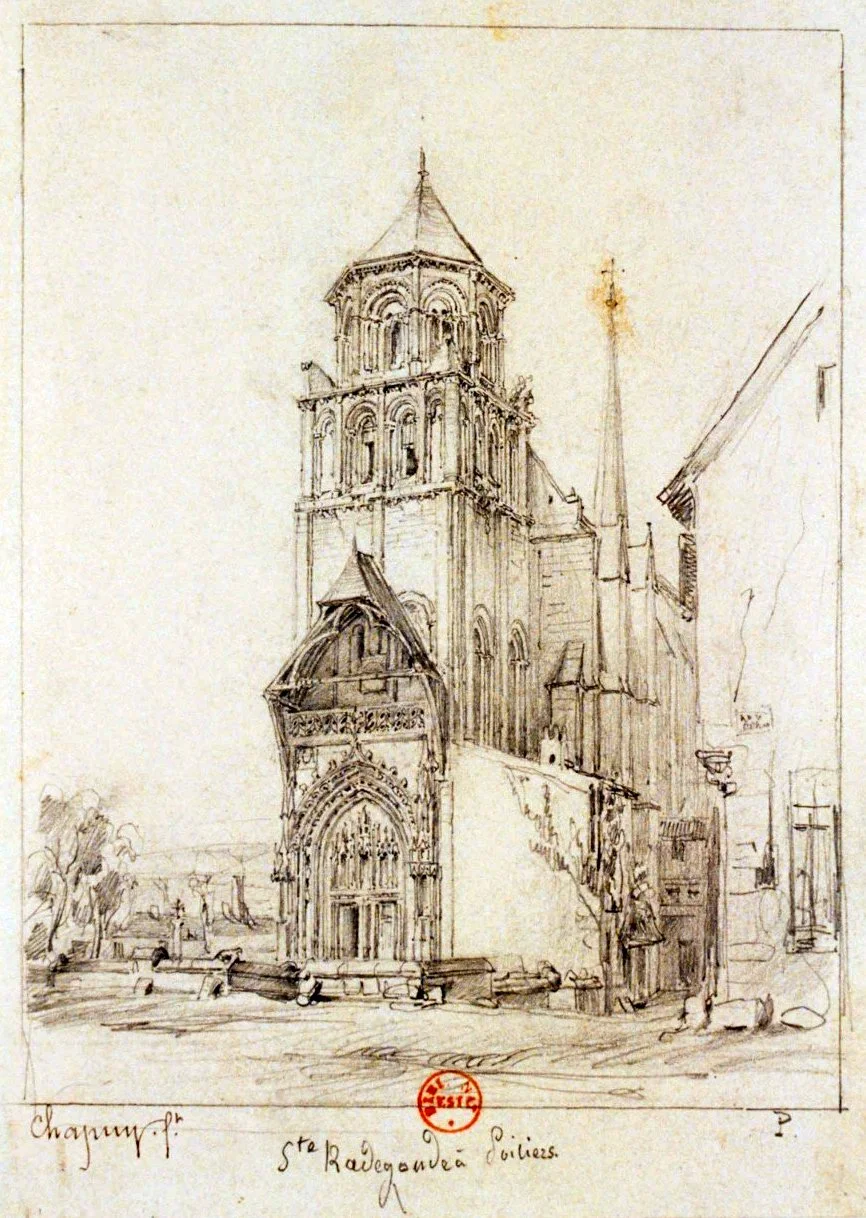

The Church of Sainte-Radegonde in Poitiers, where Mathurin was likely baptized, originated in the 6th century as Sainte-Marie-hors-les-Murs, a funerary chapel built outside the city walls by Queen Radegonde for the nuns of her monastery. After her burial there in 587, it became a major pilgrimage site and was renamed in her honour. Rebuilt after a fire in the late 11th century, the church retains a Romanesque choir with an ambulatory and radiating chapels, while its nave was later reconstructed in the Angevin Gothic style. A Flamboyant Gothic portal and bell-tower were added in the 15th century. The crypt, which holds Radegonde’s sarcophagus, remains a focus of devotion and contains numerous votive offerings. Classified as a Monument historique in 1862, the church continues to reflect more than a thousand years of architectural and religious history.

Sainte-Radegonde in Poitiers, 19th-century drawing by Nicolas Marie Joseph Chapuy (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The church façade today, photo by Ovoid (Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Life in 17th-Century Poitiers and Emigration to New France

Location of Poitiers in France (Mapcarta)

During the second half of the seventeenth century, Poitiers was a provincial capital marked by religious tension and royal centralization. Louis XIV’s reforms placed greater authority in the hands of royal officials (intendants), reducing the power of local magistrates and guilds and tightening control over trade and taxation. Daily life for townspeople became more regulated: municipal privileges were curtailed, and new taxes financed the Crown’s military campaigns. The city’s university and church institutions remained influential, yet economic opportunities were limited outside the legal, clerical, and artisan trades. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 brought repression of Poitiers’ remaining Protestants—conversions, confiscations, and the departure of many skilled workers—which disrupted families and local commerce.

Later historic documents confirm that Mathurin worked as a matelot (a sailor or crewman). In this historic context in Poitiers, he might have looked to New France for better prospects. Maritime networks linked Poitiers with the Atlantic ports of La Rochelle and Rochefort, where shipyards, supply convoys, and colonial trade were expanding. For a man in his mid-twenties with seafaring or river-transport experience, emigration could offer steady employment moving goods and settlers along the St. Lawrence River, freedom from mounting royal controls and guild restrictions at home, and the chance to establish himself in a growing colony that valued such skills.

Mathurin made the fateful decision to leave France, arriving in New France by the summer of 1689. He settled in Québec, where he continued his trade as a sailor and began to establish roots in the colony.

On January 8, 1690, notary Gilles Rageot drafted a marriage contract between Mathurin and Marie Anne Ferré (or Feret), daughter of maître de barque (a small-boat owner and navigator) Pierre Ferré and Marie Lannon, residents of the parish of Notre-Dame in Québec. Mathurin was about 27 years old and was described as a matelot (a sailor or crewman); Marie Anne was 14 years old.

Legal Age to Marry and Age of Majority

In New France, the legal minimum age for marriage was 14 for boys and 12 for girls. These requirements remained unchanged during the eras of Lower Canada and Canada-East. In 1917, the Catholic Church revised its code of canon law, setting the minimum marriage age at 16 for men and 14 for women. The Code civil du Québec later raised this age to 18 for both sexes in 1980. Throughout these periods, minors required parental consent to marry.

The age of majority has also evolved over time. In New France, the age of legal majority was 25, following the Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris). This was reduced to 21 under the British Regime. Since 1972, the age of majority in Canada has been set at 18 years old, although this age can vary slightly between provinces.

Six months later, Mathurin’s occupation was again mentioned in two agreements dated June 12, 1690, between himself and the man who would have been his father-in-law, Pierre Ferré, on behalf of his daughter Marie Anne. Mathurin was qualified as a matelot (a sailor or crewman) on a boat named La Sainte-Anne.

For reasons unknown, Mathurin and Marie Anne later annulled their contract and never married.

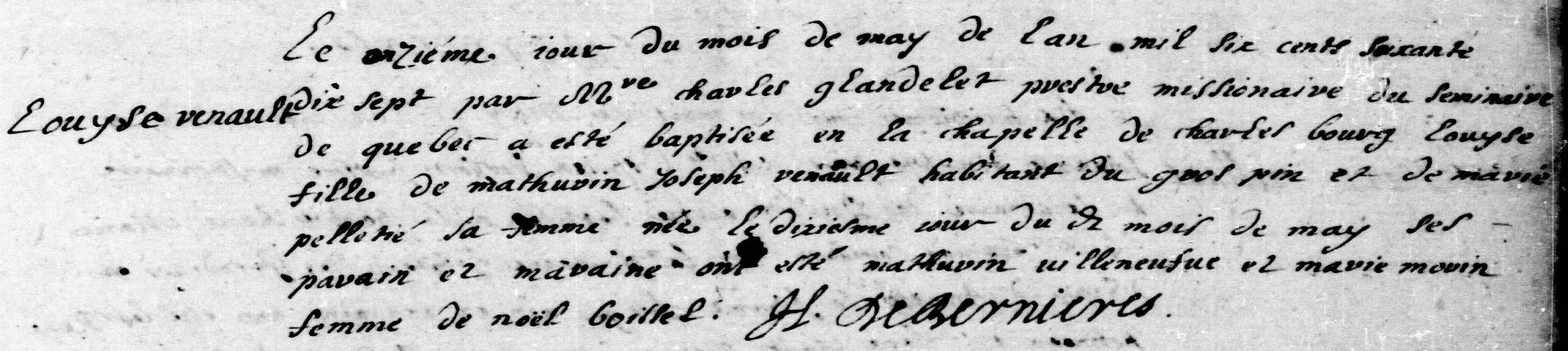

Louise Renaud, daughter of Mathurin Renaud and Marie Marguerite Pelletier, was born on May 10, 1677. She was baptized the following day in the chapel of Charlesbourg. Her parents were recorded as residents of Gros-Pin. Her godparents were Mathurin Villeneuve and Marie Morin. [Louise’s surname appeared under various phonetic spellings: Renault, Regnault, Renaut, etc.]

1677 baptism of “Louyse Renault” (Généalogie Québec)

Gros-Pin began as a small hamlet within the Jesuit seigneurie of Notre-Dame-des-Anges on the corridor between Québec (Saint-Roch district) and Charlesbourg. By 1668, Intendant Jean Talon had ordered the opening of the road linking these new villages to Québec, and by the 1672 census Gros-Pin held about seven families (alongside the nearby Petite-Auvergne and the main village at Charlesbourg).

Marriage and Children

On July 19, 1691, notary Gilles Rageot drew up a marriage contract between Mathurin and Louise in Québec. He was 28 years old, a resident of Québec, originally from the parish of Sainte-Radegonde in Poitiers. She was 14 years old, living with her mother and stepfather, Pierre Canard, in the parish of Saint-Jérôme in Petite-Auvergne. Louise’s witnesses were her mother and stepfather, her brother Pierre, her sister Anne, her godparents, and several other friends and family members. Mathurin’s witnesses were Pierre Normand de Labrière, Charles Normand, Pierre Lereau, Catherine Normand, Marguerite Chalifou, and several others.

The contract followed the Coutume de Paris. Louise received 200 livres from her mother and stepfather as an advance on her inheritance. Her dower was set at 500 livres, and the préciput at 150 livres.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children. Inventories were drawn up after death in order to list all the community's assets.

The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him. The preciput was a benefit conferred by the marriage contract, usually on the surviving spouse, granting them the right to claim a specified sum of money or property from the community before the rest was divided.

The marriage contract (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, November 2025)

Though several witnesses could sign the marriage contract, the future bride and groom were unable to do so.

Mathurin and Louise married on July 23, 1691, in the parish of Saint-Charles in Charlesbourg. The couple’s witnesses were Pierre Canard (Louise’s stepfather), Charles Normand, Pierre Normand de Labrière, Jean Bado [Badeau], Samuel Vignier, André Spénard, Pierre Bourleton (Louise’s brother-in-law), and Pierre Renaud (her brother).

Mathurin and Louise had at least 18 children:

[anonymous] (1693–1693)

Marie Charlotte (1694–1771)

Jean Baptiste (1696–?)

Marie Louise (1697–1717)

Marguerite (1698–1718)

Louis (1700–1774)

Marie Thérèse (1701–1701)

Radegonde (1702–1703)

Marie Angélique (1703–1772)

Pierre (1706–?)

Josèphe Madeleine (1707–1710)

Louis Charles (1709–?)

Marie Louise (1710–1793)

Marie Madeleine (1712–1746)

Marie Catherine (1714–1714)

Louis (1715–1722)

Antoine (1717–1781)

Jean Marie (1720–?)

On February 20, 1692, Mathurin was recorded as a 29-year-old patient in the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. He was noted there again on January 7, 1698, when he remained hospitalized for 18 days. On both occasions, the reason for his admission is unknown.

Land Transactions

Mathurin and Louise were involved in several land transactions over their lifetimes. They initially settled in the Charlesbourg area before eventually living in Québec City:

March 24, 1694: Mathurin purchased a plot of land and habitation located on “the great road that goes from Québec to Charlesbourg on the left-hand side” in the seigneurie of Notre-Dame-des-Anges for 45 livres from cooper Pierre Leroy. The land measured two arpents and nine perches of frontage (facing the St. Lawrence) by about 26 arpents in depth. Mathurin agreed to take on the future payments to the seigneurs: one sol per arpent in area, plus two live capons in seigneurial rente, plus [three?] deniers in cens on the feast day of Saint Étienne, the day following Christmas. Mathurin was described as an habitant of Gros-Pin in the parish of Charlesbourg.

May 25, 1694: Mathurin and Louise sold half a plot of land and habitation measuring 40 arpents located in the village of L’Auvergne (Charlesbourg) to Québec merchant Pierre Duroy for 50 livres. Louise had received the land as part of her deceased father’s succession.

March 30, 1701: Mathurin purchased an habitation in Saint-Romain, located in the seigneurie of Saint-Ignace, from François Duclos and Jeanne Bruneau for 50 livres. The land measured three arpents of frontage by twenty arpents in depth, of which three or four arpents had been cleared and the rest remained wooded. Mathurin promised to pay three livres and three live capons in seigneurial rente annually, plus three sols in cens. He also agreed to inhabit the land, keep the roads maintained, and grind his grain at the closest mill to the seigneurie.

July 14, 1702: Mathurin and Louise sold a quarter of a plot of land in Gros-Pin to her brother Michel Renaud for 200 livres, payable over five years. The land measured two arpents and nine perches in frontage by about seventeen arpents in depth. Louise had received the land after the death of her stepfather, Pierre Canard.

September 30, 1710: Mathurin and Louise sold their land purchased nine years earlier in the village of Saint-Romain to Jean Baptiste Fournier for 55 livres. Mathurin was described as a navigateur (boat navigator) from Québec City. In a shaky hand, he signed the sale contract with his initials: MPD.

Mathurin’s signature in 1710

Half-timbered house in Québec’s lower town (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, November 2025)

October 13, 1712: Mathurin rented a lot and house on rue Champlain in Québec from Pierre de Niort de La Minotière. [The details are unknown, as the original document was not located.]

January 21, 1713: Mathurin and Louise sold their land on “the great road that goes from Québec to Charlesbourg,” purchased in 1694, to the Ursulines of Québec. Mathurin was described as an habitant and maître de barque (river boat captain) of Québec.

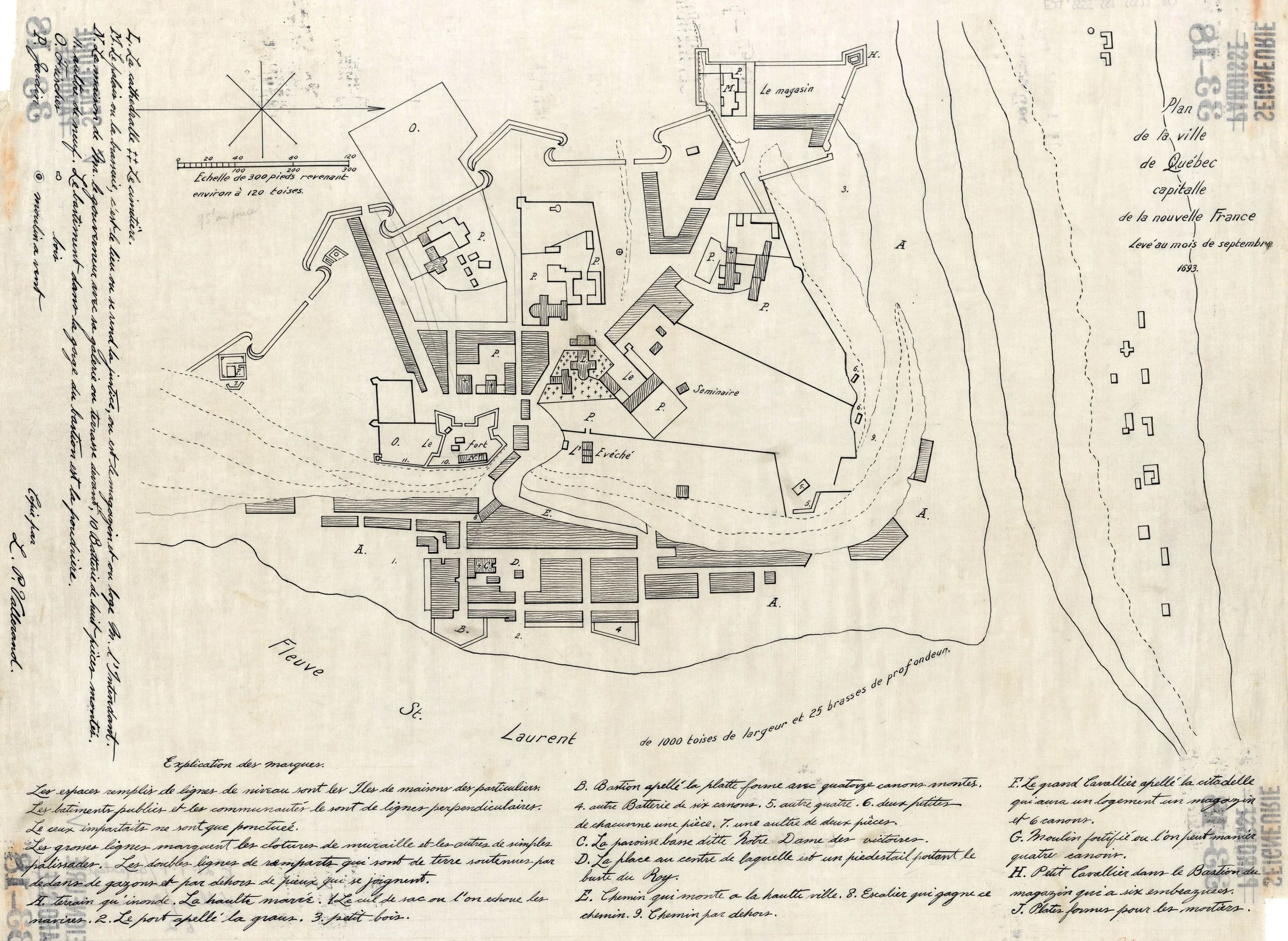

January 23, 1713: Mathurin purchased a lot and half-timbered house with a stone foundation located on rue sur le Quai du Cul-de-Sac in Québec City from Antoine Carpentier and Thérèse Mailloux for 1,170 livres. The lot measured about 19 feet of frontage facing the St. Lawrence River, with the depth extending from the river to the street commonly called Demeule or Champlain. Mathurin was described as a navigateur (boat navigator) from Québec City.

April 27, 1714: Mathurin leased the house on rue Demeule (or rue de Champlain) in Québec City to master butcher Louis Bardet. Mathurin was described as a maître de barque (river boat captain) of Québec. [The details are unknown, as the notarial record is damaged.]

July 12, 1715: Mathurin sold a portion of the lot on rue Demeule in Québec City to Pierre Corriveau for 600 livres. Mathurin was described as a navigateur (boat navigator).

April 30, 1717: Mathurin and Louise sold a quarter of the house on rue Demeule in Québec City to navigator Jacques Coquet and Anne Frappier for 240 livres. The record indicates that the ground floor was covered with planks and included a chimney. Mathurin was described as a maître de barque (river boat captain).

1720 map of Québec City (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Before the Courts

Between 1692 and 1734, Mathurin appeared in more than a dozen court actions. Early in life, while settled at Gros-Pin (Charlesbourg), he was involved in disputes typical of rural habitants—land boundaries, debts, livestock, and ferry tolls. Later, established at Québec as a maître de barque, he engaged in minor commercial litigation and one notable assault case. The frequency and range of his appearances show him as an active, assertive participant in local commerce and community life, reflecting both the rough edges and opportunities of colonial society.

Early criminal case (1692)

In August–September 1692, Mathurin and Jean-Baptiste Duquet were convicted of assaulting Jean Thierry, an officer responsible for enforcing the King’s rights. The court ordered them each to pay 30 livres in damages and expenses. Two Dussault brothers were fined smaller amounts, and others were cited for serving the men liquor at prohibited hours.

Property and civil disputes (1693–1698)

1693 – in Petite Auvergne: After a bidder withdrew from the sale of land formerly held by architect Jean Lerouge, Mathurin’s offer was declared valid, and the property was re-auctioned.

1696 – vs. Pierre Renaud: A case between Mathurin and his neighbour at Gros-Pin, concerning a verbal agreement or contract witnessed by several men; both were summoned before the seigneurial court of Notre-Dame-des-Anges.

1698 – vs. Anne Jousselot, widow Dubeau: She accused Mathurin of cutting wood on her property; a surveyor, Louis-Marin Boucher, was appointed to re-establish the boundary.

1698 – vs. Pierre Duroy: Duroy, a butcher and resident of nearby Saint-Jérôme, complained that Mathurin and his wife Louise had encroached on his land and opened a road through it. The Jesuit seigneurs were asked to arbitrate, since the route crossed their domain.

Local debts and minor claims (1699–1705)

Mathurin frequently appeared before Judge Guillaume Roger of the prévôté of Québec for small civil cases typical of habitants:

1699 – Tolls on the Saint-Charles River: Two men, Jean Lallemand and Jean Sigouin, were condemned to pay Mathurin small sums—25 and 27 sols—for ferry passage he had operated five years earlier.

1699 – vs. Pierre Jean dit Godon: A mixed ruling ordered Mathurin to deliver a dog-hair blanket and fabric, while Godon was to complete unfinished work at Mathurin’s habitation.

1699 – vs. Pierre Renaud (second case): Mathurin was authorized to produce witnesses in another debt dispute.

1699 – vs. Jean Courtois: Mathurin sought payment of a debt owed by Courtois’s late brother; the court required proof of inheritance before enforcing the claim.

1699 – vs. François Dubois: A series of quarrels at Gros-Pin concerned mistreated pigs, alleged insults about Mathurin’s wife, and mutual accusations of threats. After repeated hearings and witness testimony (including Jeanne Bourret and Anne Jousselot), the judge dismissed the parties from court.

1700 – vs. Marie Pelletier (his mother-in-law), the widow Canard: Mathurin was condemned to pay her 34 livres 16 sols in exchange for a cow.

1704 – vs. Marin Courtois: Mathurin won judgment for 4 livres 15 sols for eels supplied to Courtois’s late brother.

1705 – vs. Jesuits: He was ordered to pay 18 livres 5 sols in overdue rent on his land in the Jesuit seigneurie.

1705 – vs. Michel Renaud: Mathurin won 51 livres for land he had sold to Renaud.

Later court cases (1720–1729)

1720 – vs. Pierre Glinel: He sued for payment of 50 livres’ worth of hay.

1721–1722 – vs. Jean-Baptiste Grenet: Grenet accused Mathurin, his wife Louise, and their son of assaulting Grenet’s wife and daughter on rue Champlain in Québec. After interrogations and witness statements, Mathurin was fined 40 livres in damages and costs. On appeal, the Conseil supérieur first upheld the verdict (January 1722) but later dismissed both sides and forbade further quarrels (March 1722).

1723 – vs. Louis Dugal: Mathurin won a debt case, though 100 sols were deducted for an earlier partial payment.

Final record (1734)

Still living on rue Demeule (or Champlain), Mathurin filed a complaint against Marie-Françoise Rinfret, demanding repayment of 11 livres 15 sols for a stolen silver snuffbox belonging to his wife.

Working on the River

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, November 2025

Mathurin’s working life illustrates the fluid nature of trades in colonial Québec. Beginning as a matelot (sailor) in 1690 aboard the Sainte-Anne, he soon operated a ferry for the Jesuits on the Petite Rivière Saint-Charles. By 1694, he had settled as an habitant at Gros-Pin, combining farming with seasonal river work. Around 1708, he shifted decisively toward navigation. From 1710 onward, notarial acts describe him as a navigateur and maître de barque—the owner and captain of a commercial riverboat based in Québec City.

The following notarial records pertain to Mathurin’s work:

April 3, 1693: Mathurin hired Pierre Renaud, his brother-in-law, as a general labourer for 60 livres. Mathurin was described as a passager fermier (ferry operator) for the Compagnie de Jésus (the Jesuits) on the Petite Rivière Saint-Charles. Pierre was to assist him on the river and help with domestic tasks until the fall.

September 15, 1708: Mathurin acquired a vessel or rowboat by auction from navigator Michel Derome dit Descarreaux for 1,120 livres. Derome had been unable to pay his debts to Joseph Amiot, sieur de Vincelotte.

September 22, 1708: Michel Derome dit Descarreaux accepted half ownership in the rowboat, including all its rigging and equipment, in partnership with Mathurin for 578 livres. This confirms that the two men were joint owners and operators of the vessel following the court-ordered adjudication a week earlier.

March 6, 1710: Mathurin leased his 20-ton capacity boat, named La Marie Magdeleine, to Joseph Amiot, the seigneur of Vincelotte, for use during the upcoming navigation season starting in the spring and lasting until the end of the same year. Mathurin would undertake boat trips on Amiot’s behalf and receive payment of 180 livres per month during the navigation season. [This is presumably the same rowboat Mathurin had acquired two years earlier.]

November 20, 1714: Mathurin hired Guillaume Corriveau, a ship carpenter, to repair his boat. Mathurin was described as a navigateur (boat navigator). [The details are unknown, as the notarial record is damaged.]

April 4, 1717: Mathurin sold his boat to Thomas de Laforest and Jean Forton, master ship carpenter, for 400 livres. Mathurin was described as a navigateur (boat navigator).

In 1721, Mathurin agreed to work contracts for two of his sons:

April 25, 1721: Louis Palin was hired as a maître de chaloupe (rowboat captain) by Ignace Juchereau de St-Denis. [The details are unknown as the original document was not located.]

May 7, 1721: Pierre Palin was hired by merchant Nicholas Mayeux to assist him on his boat for 10 livres per month.

Mathurin and Louise’s Final Years

On December 15, 1736, in declining health and advancing age, Mathurin and Louise dictated their last wills and testaments to notary Jacques Nicolas Pinguet de Vaucour at their home on rue Champlain in Québec. Mathurin was described as infirme de corps (physically infirm) and Louise as saine de corps (physically healthy). Both were sains d’esprit (of sound mind).

Their joint testament requested the following:

That all their debts be paid.

That after their deaths, they be buried in the parish cemetery of this city if they died there, and that the burials be done at the lowest possible cost.

That in the year of their death, 25 livres be spent on Requiem masses for the repose of their souls.

That 100 livres be given to the poor of the parish.

That anything remaining after this be shared equally among their children and heirs.

The couple named Jacques Gagon [Gagnon] as their executor.

Death of Louise

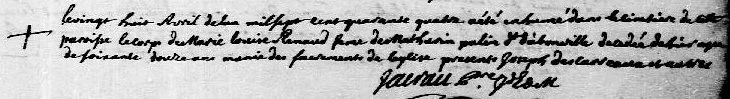

Louise Renaud died at the age of 66 on April 27, 1744. She was buried the following day in the Notre-Dame parish cemetery in Québec. [The burial record mistakenly states that she was 72 years old.]

1744 burial of Louise Renaud (Généalogie Québec)

After his wife’s death, Mathurin began to settle his financial affairs.

On August 14, 1747, Mathurin donated 620 livres 17 sols and 6 deniers to his daughter Angélique, the widow of Jean Robert Demitre. He declared that he was “of an advanced age, unable to work to earn a living,” and that of all his children, only Angélique "was willing to take care of him, which she had done for three years without him providing her with much of anything.” Angélique agreed to take in her approximately 84-year-old father, feed him, and care for him in sickness and in health, and “to show him the same consideration and attention that she had shown him before,” but she would not be able to use the sum given “except with the consent of her said father, who would remain her master.” Angélique also agreed to have her father buried after his death and to have low masses said for him.

The following month, on September 8, 1747, Mathurin and his children sold the lot and house located on rue Demeule (or Champlain) to Gilles Hocquart, the Intendant of New France, for 1,241 livres 5 sols. The lot was part of “those His Majesty judged appropriate for the establishment of a new construction site at the place commonly called the Cul-de-Sac of the Lower Town.” The house had already been torn down when the notarial document was drawn up.

Mathurin eventually went to live with his son Antoine and his family. On January 14, 1756, Antoine and his wife agreed to house, feed, and care for his father in sickness and in health for the remainder of his life.

Death of Mathurin

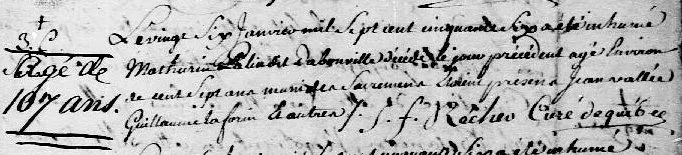

Mathurin Palin dit D’Abonville lived only eleven days after the agreement with his son was drafted. He died at approximately 93 years of age on January 25, 1756, and was buried the following day in the Notre-Dame parish cemetery in Québec. [The burial record mistakenly states that he was 107 years old.]

1756 burial of Mathurin Palin dit D’Abonville (Généalogie Québec)

Legacy on the St. Lawrence

Mathurin Palin dit D’Abonville and Louise Renaud embodied the determination of early settlers who built their lives along the St. Lawrence River. From his beginnings as a sailor in the service of others, Mathurin became a maître de barque operating his own vessel from Québec City—an achievement that reflected both skill and perseverance in a demanding trade. Through decades of work, landholding, and family life, Mathurin and Louise adapted to the challenges of colonial society while raising a large family whose descendants would remain in the region for generations. Their story mirrors that of many families who shaped New France through labour, resilience, and an enduring connection to the river that sustained them.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Poitiers > Baptêmes> 1626-1628 > collection communale 3380 > Saint-Jean-Baptiste," digital images, Archives départementales des Deux-Sèvres et de la Vienne (https://archives-deux-sevres-vienne.fr/ark:/28387/vta9ebd1cce2fbc931e/daogrp/0/2 : accessed 3 Nov 2025), baptism of Françoise Matias, 1 Feb 1626, Poitiers (St-Jean-Baptiste), image 2 of 83.

"Focus : L’Église Sainte-Radegonde Poitiers," Grand Poitiers (https://www.poitiers.fr/sites/default/files/2022-05/FOCUS_EGLISE_SAINTE-RADEGONDE_POITIERS.pdf : accessed 3 Nov 2025).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/59522 : accessed 3 Nov 2025), baptism of Louise Renault, 11 May 1677, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/67439 : accessed 3 Nov 2025), marriage of Mathurin Palin and Louise Renauld, 23 Jul 1691, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/167771 : accessed 4 Nov 2025), burial of Marie Louise Renaud, 28 Apr 1744, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/251840 : accessed 4 Nov 2025), burial of Mathurin Palin Dabonville, 26 Jan 1756, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

“Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968,” digital images, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_31480064 : accessed 3 Nov 2025), hospital entry for Mathurin Palin dit Donbonville, citing original data: Drouin Collection, Institut Généalogique Drouin.

“Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968,” digital images, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_31480168 : accessed 3 Nov 2025), hospital entry for Mathurin Pallin, citing original data: Drouin Collection, Institut Généalogique Drouin.

"Archives de notaires : Gilles Rageot (1666-1691)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4083923?docref=py5YSUAuhD5zQWUoRj2x-A : accessed 3 Nov 2025), marriage contract between Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville and Louise Renaud, 19 Jul 1691, images 1119-1120 of 1348.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-LWNT?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=1461&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), land sale by Pierre Leroy to Mathurin Pallin dit Dembonville, 24 Mar 1694, images 1462-1463 of 3409; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-LWJK?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=1559&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), land sale by Mathurin Palin dit Dembonville and Louise Regnault, 25 May 1694, images 1560-1561 of 3409; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1682-1709 // François Genaple," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-VQ9J-V?cat=koha%3A1168969&i=3206&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), land sale by François Duclas et Jeanne Bruneau to Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville, 30 Mar 1701, images 3207-3209 of 3410; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1700-1714 // Michel-Laferté Lepailleur," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LZ-G939-4?cat=koha%3A730550&i=2285&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), sale of a portion of land by Mathurin Palin and Louise Regnaud to Michel Renaud, 14 Jul 1702, image 2286 of 2467; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-W98M-1?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=648&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), land sale by Mathurin Palain dit Dabonville and Louise Regnault to Jean Baptiste Fournier, 30 Sep 1710, images 649-650 of 2820; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1708-1739 // Jean-Etienne Dubreuil," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-R3LC-HKYH?cat=koha%3A746806&i=985&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), land sale by Mathurin Palin dit Dembonville and Louise Regnaut to the Ursulines of Québec, 21 Jan 1713, images 986-988 of 2988; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-W9VW-3?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=2289&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), land sale by Antoine Carpantier and Thérèse Maillou to Mathurin Palain dit Dabonville, 23 Jan 1713, images 2290-2291 of 2820; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1753 // François Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NX-W9KS-D?cat=koha%3A963363&i=3310&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), lease of a house by Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville to Bardet, 27 Apr 1714, images 3311-3312 of 3357; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1753 // François Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-GSH4-2?cat=koha%3A963363&i=65&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), sale of a lot portion by Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville to Pierre Cauriveau, 12 Jul 1715, images 66-67 of 3387; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1753 // François Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-GSHG-L?cat=koha%3A963363&i=144&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), sale of a house portion by Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville and Louise Renaud to Jacques Coquet and Anne Frapier, 30 Apr 1717, images 145-147 of 3387; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1682-1709 // François Genaple," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-V31F-7?cat=koha%3A1168969&i=262&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), work contract between Mathurin Palin dit Dambonville and Pierre Regnault, 3 Apr 1693, images 263-264 of 3410; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5X-74JX?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=952&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), acquisition of a boat by Mathurin Palin dit Dambonville following an auction, 15 Sep 1708, images 953-954 of 1715; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5X-74JR?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=962&lang=en : accessed 3 Nov 2025), partnership between Mathurin Palin dit Dembonville and Michel Derome dit Descarreaux, 22 Sep 1708, images 963-966 of 1715; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1692-1716 // Louis Chambalon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-W9D3-5?cat=koha%3A1170051&i=262&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), boat lease by Mathurin Palain dit Danbonville to Joseph Amiot seigneur de Vincelotte, 6 Mar 1710, images 263-265 of 2820; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1753 // François Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3NX-W9KW-R?cat=koha%3A963363&i=3316&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), boat repair agreement between Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville and Guillaume Cauriveau, 20 Nov 1714, images 3317-3319 of 3357; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1709-1753 // François Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-GS8Q-1?cat=koha%3A963363&i=129&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), sale of a boat by Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville to Thomas de Lafaurest and Jean Forton, 4 Apr 1717, images 130-131 of 3387; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1702-1728 // Florent de La Cetière," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NX-XSQM?cat=koha%3A963722&i=953&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), work contract between Pierre Palin and Nicolas Mayeux, 7 May 1721, images 954-955 of 3371; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1726-1748 // Jacques-Nicolas Pinguet de Vaucour," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-2SX6-Y?cat=koha%3A963358&i=636&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), testament of Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville and Louise Renaud, 15 Dec 1736, images 637-639 of 3360; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1745-1775 // Jean-Claude Panet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-R3LF-89YX?cat=koha%3A964090&i=348&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), donation by Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville to Angélique Palin, 14 Aug 1747, images 349-351 of 3357; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1734-1759 // Christophe-Hilarion Dulaurent," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L7-P9NT-F?cat=koha%3A746918&i=2509&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), sale of a lot by Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville and his children to Gilles Hocquart, 8 Sep 1747, images 2510-2512 of 2836; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1756-1759 // Jean-Baptiste Decharnay," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L3-L9D9-V?cat=koha%3A704840&i=469&lang=en : accessed 4 Nov 2025), agreement between Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville and Antoine Palin, 14 Jan 1756, image 470 of 2891; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 4 Nov 2025), "Contrat de mariage entre Mathurin Palin dit Dabonville, fils de Pierre Palin et de feue Florence Matial, de la paroisse de Sainte Radegonde de la ville et évêché de Poitiers; et Marie-Anne Ferré, fille de Pierre Ferré, maître de barque et de Marie Lasnon, de la rue Cul de Sac en la paroisse Notre Dame de la ville de Québec," notary Gilles Rageot, 8 Jan 1690.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 4 Nov 2025), " Traité entre Pierre Ferré, maître de barque, de la ville de Québec, et Mathurin Palin, matelot dans le navire nommé La Ste Anne," notary Gilles Rageot, 12 Jun 1690.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 4 Nov 2025), "Bail d'une maison et emplacement situés rue Champlain; par Pierre de Niort de Laminotière, à Mathurin Palin dit Dambonville," notary F. de Lacetière, 13 Oct 1712.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 4 Nov 2025), "Engagement en qualité de maître de chaloupe de Louis Palin, par Mathurin Palin, son père, à Ignace Juchereau de St Denis, écuyer," notary F. de Lacetière, 25 Apr 1721.

Results of Advitam research regarding Mathurin Palin, online database and digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/resultats?state=eyJzZWFyY2hTdGF0ZSI6eyJwYWdlIjoxLCJzZWFyY2hUeXBlIjoiU0lNUExFIiwic2VhcmNoUGFyYW1zIjp7ImNyaXRlcmlhIjpbeyJuYW1lIjoidGV4dE5ldHRveWUiLCJzb2xyU2VhcmNoVHlwZSI6IkNPTlRJRU5UX1RPVVNfTEVTX01PVFMiLCJ2YWx1ZSI6Ik1hdGh1cmluIFBhbGluIiwib3BlcmF0b3IiOiJldCJ9LHsibmFtZSI6ImNvdGVDb21wbGV0ZSIsInNvbHJTZWFyY2hUeXBlIjoiQ09URV9JTkZFUklFVVIiLCJ2YWx1ZSI6Ik1hdGh1cmluIFBhbGluIiwib3BlcmF0b3IiOiJvdSJ9XSwiY29kZXNDZW50cmVBcmNoaXZlIjpbXX19fQ : accessed 3 Nov 2025), 44 results.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/palin/-pallain/-dabonville : accessed 2 Nov 2025), entry for PALIN / PALLAIN / D'ABONVILLE, Mathurin (person #243131), updated on 7 Dec 2021.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/6764 : accessed 3 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Mathurin Jean PALIN DABONVILLE and Marie Louise Renaud, union 6764.

Jacqueline Sylvestre, "L’âge de la majorité au Québec de 1608 à nos jours," Le Patrimoine, Feb 2006, volume 1, number 2, page 3, Société d’histoire et de généalogie de Saint-Sébastien-de-Frontenac.