Jean Poisson and Angélique Franche dite Laframboise

Explore the life story of Jean Poisson, a French soldier who took part in several historic Canadian battles, before settling down with a Canadienne near Montreal and becoming a farmer.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jean Poisson (1728-1805)

A Journey from La Sarre Soldier to Montréal-Area Settler

Researched and written by Donald Clark White and Kim Kujawski

Civilization usually progresses like the tides, with a certain ebb and flow. However, like geologic evolution, tectonic scale and catastrophic events also play a role. To live through such leaps of civilization is one thing; to contribute to them is another. Jean Poisson, a mid-eighteenth-century French soldier from the Franco-German contested province of Lorraine, emerged as a significant player in several great leaps of our society. First, he was shipped to New France to fight the English-allied Iroquois, and then against the English themselves. This was a clash of great powers. Poisson fought in a number of the most pivotal New York and Québec engagements, culminating in the capture of Québec by the English in 1759. Upon settling near Montréal and establishing a family on land he diligently cleared and cultivated, Poisson became the quintessential frontiersman of Québec. From his European origins to his new life in North America, from a French soldier to adapting to English rule, and from the rugged wilderness to a settled existence, he indelibly contributed to the formation of Canada as an emigrant, soldier, father, and farmer.

From Repaix to New France

Jean Poisson’s birthplace was the parish of Saint-Paul in Repaix, in the old province of Lorraine. Located in the far northeast of France, the village now resides within the department of Meurthe-et-Moselle. With a minuscule population of fewer than 100 residents, called Respaliens, Repaix retains its character as a tranquil farming community.

Location of Repaix in France (Google Maps)

Church of Saint-Paul in Repaix (2022 photo by Rauenstein, Wikimedia Commons)

Jean’s parents were Christophe Poirson and Marie Octave. His baptism record in Repaix has not been found, as the parish records from 1692 to 1752 have been lost. Jean was likely born around 1728. His surname has been spelled Poisson and Poirson on Canadian documents. His given name has also been recorded as “Jean Baptiste.”

On March 31, 1751, at the age of about 23, Jean enlisted as a soldier in the Compagnies franches de la Marine. He became a part of the La Sarre Regiment, serving in the company of Laferté de Mung within the Second Battalion.

Defending New France

The La Sarre Regiment primarily recruited soldiers from the Lorraine region. Jean’s Second Battalion was sent to New France during the Seven Years’ War, and due to various factors like deaths, desertions, and discharges, only a few of its initial members ever returned to France.

Ordonnance flag of La Sarre regiment (Wikimedia Commons)

During the 1750s, tensions were rising in Canada, leading to Jean’s Second Battalion receiving orders from Louis XV to reinforce the troops in New France. The battalion set sail from Brest on April 3, 1756, aboard the ship Héros. It arrived in Québec on May 12, with the final ships of the regiment landing on May 31.

The Second Battalion was then under the command of Étienne-Guillaume de Senezergues, serving under the new overall army commander for New France, Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm. This marked the beginning of a significant chapter in Jean’s military service, closely tied to the events unfolding in a continent embroiled in conflict.

The regiment departed Québec on June 6 and 7, travelling via smaller vessels along the St. Lawrence River to reach Fort Frontenac on Lake Ontario’s northern shore. There, they joined forces with the Béarn and Guyenne infantry regiments. Montcalm, the commanding officer, arrived at Fort Frontenac on July 29 to lead an attack on Forts Ontario and Oswego (also known as Fort Chouaguen). Leading a combined force of approximately 2,000 regular troops, 1,000 militia, and 200 indigenous fighters, they headed to Niaouré (modern-day Sackets Harbor, southwest of Watertown, New York). On August 10, the contingent left their camp in the direction of Fort Oswego, 20 leagues away. After capturing Fort Ontario on August 12, Montcalm seized their captured cannon, adding to his own artillery and headed further inland.

The French troops, armed with 51 cannon, mortars, and howitzers, then laid siege to Fort Oswego, situated at the mouth of the Oswego River (northwest of Syracuse, New York). On August 14, the British commander at Fort Oswego was killed, forcing his second-in-command to surrender both forts. The 2,000-strong garrison was taken prisoner. This victory marked a significant gain for the French in their efforts to control key strategic positions in the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley during the early stages of the French and Indian War. On August 17, half the prisoners were sent to Montréal, escorted by a picket; on the 18th, the other half was sent by Méritens, lieutenant of the Sarre grenadiers, with thirty grenadiers and 20 soldiers drawn from all the regiments. They arrived in Montréal on the 24th. The rest of the La Sarre regiment arrived on the 27th and set up camp the following day in Laprairie. In November, the La Sarre regiment received orders to take up winter quarters near Montréal.

"Capitulation of Fort Oswego, August 1756," 1877 engraving by John Henry Walker (Wikimedia Commons)

“Montcalm receiving on August 9, 1757, the English captain Mr. Fesch (…) on behalf of Lieutenant-Colonel Young and George Monro to negotiate the surrender of Fort William Henry” (Wikimedia Commons)

During the summer of 1757, Jean Poisson and his regiment joined a sizable French force that advanced southward via the Richelieu River and Lake Champlain with the objective of capturing Fort William Henry at the southern tip of Lake George. The French, numbering around 8,000 soldiers, encircled the fort and blocked its supply routes. During the five-day siege, the British garrison inside the fort, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Monro, faced dire circumstances, including depleting supplies and increasing casualties. Following days of bombardment and negotiations, Monro surrendered the fort to Montcalm on August 9. The terms of surrender permitted the British garrison to depart with their weapons and honours.

By August 16, French forces were en route to Carillon (the French name for Fort Ticonderoga, situated on the portage between Lake George and Lake Ticonderoga). Smaller French units remained to control the former English fortifications, but Jean returned to his battalion’s winter quarters at Île-Jesus (an island just north of the Island of Montréal) in October 1757.

Establishing Roots

Although Jean had the option to return to France at the conclusion of his military service, it seems he had already decided, within a year and a half of his arrival, to remain in New France. On November 9, 1757, he received a land concession on the southern coast of Île-Jésus from the Séminaire de Québec [the present-day city of Laval encompasses the entirety of the island]. He was recorded as “Jean Poirson, soldat du regiment de Lasarre, compagnie de Meune." The land measured three arpents frontage (facing the Rivière des Prairies) by twenty arpents deep. Jean’s land was on the seigneurie of Île-Jésus, where the Seminary was its seigneur. The notarial act was drawn up by notary Charles François Coron, in which Jean declared not knowing how to sign.

Extract of Jean’s 1757 land concession (FamilySearch)

Jean further cemented his intentions to stay in Canada just nine days after receiving his land concession. Now that he had a property on which to build a house, he was ready to marry and start a family. On November 18, 1757, Jean and Angélique Franche dite Laframboise appeared in notary Gervais Hodiesne’s office in Montréal to have a marriage contract drawn up. Jean was recorded as a soldier residing in Pointe-Claire. At 24 years of age, Angélique was legally a minor, and her father was deceased. Her brothers Joseph and Vincent were present and consented on her behalf. The contract followed the standard agreements of the Coutume de Paris. The couple was married in the parish church of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire three days later. As he was still in active military service, Mr. de Senezergues had given Jean permission to marry, and M. Deman had certified that Jean was not already married in France.

Marriage Contracts and the Coutume de Paris

In the 18th century, marriage contracts were signed before a notary in over 60% of marriages. If a contract was signed, it was normally done several days or weeks before the wedding. The average was three weeks, which corresponded with the time it took to publish three marriage bans on three consecutive Sundays. The signing was normally attended by many family members and friends, and often, high-ranking members of society. In order not to ruffle any feathers, the notary had to ensure that the order of the signatures (or marks if they were unable to sign) matched the order of their rank. Legally speaking, marriage created a new family unit with regulations dictated by the Coutume de Paris (the Custom of Paris). This meant that in most cases, the couple married according to the “communauté des biens” regime (community of property). Upon marriage, all movable and immovable property of the spouses, whether purchased or acquired, entered the community and was administered exclusively by the husband.

Extract of Jean and Angélique’s 1757 marriage contract (FamilySearch)

Angélique was the 24-year-old daughter of André Frye dit Laframboise and Marie Louise Bigras. She was the youngest child of their nine children. On documents, she was sometimes called “Marie Angélique.” The great irony here is that her father André was born Joseph Frye, an English Quaker likely from Kittery, Maine. In 1695, he was abducted by French-allied Abenaki from his home and family in Kittery. He endured over a decade in captivity with the Abenaki until he was freed around 1706. Afterward, he converted to Catholicism and was naturalized in 1710, adopting the name André. In 1713, he married Marie Louise Bigras, who was the granddaughter of a Fille du roi and a voyageur. This union brought together the daughter of an English Quaker and a French infantryman who was fighting the English.

As was customary in New France, “dit” names were involved. Joseph Fry became André Frye (sometimes Franche) dit Laframboise and daughter Angélique used dite Laframboise as well. According to some sources, Jean Poisson was dubbed “dit Vadeboncoeur” (“goes with a merry heart”) but he doesn’t appear to have used this name after his military days were over.

Military Battles: Carillon, the Plains of Abraham and Sainte-Foy

Despite being a newly married man and soon-to-be father, Jean was still a soldier under active military duty. In June of 1758, Montcalm’s forces from Montréal were mobilized to the southern end of Lake Champlain. Tactical moves between Lake Champlain and Lake George culminated in the July 8 battle of Carillon, where French forces successfully recaptured the English-held Fort Ticonderoga. Montcalm had led a French army of nearly 4,000 men to victory against an English force numbering 16,000. Following the battle, the troops dedicated many months to fortifying Fort Ticonderoga. On November 6th, they began their journey to winter quarters, leaving detachments from various regiments, including 30 men from the La Sarre regiment, stationed at Carillon.

“The Victory of Montcalm’s Troops at Carillon” by Henry Alexander Ogden (Wikimedia Commons)

We don’t know for certain whether Jean Poisson fought in the Battle of Carillon. This uncertainty arises from the fact that the battalion departed for winter quarters on November 6th, while Jean was present at his son’s baptism on November 3rd in Pointe-Claire. During this baptism, he was listed as a soldier of the Béarn Regiment, in contrast to his previous affiliation with La Sarre from his enlistment through his 1757 wedding. It’s worth noting that the Béarn Regiment was actively involved in the same campaigns as La Sarre and took part in the Battle of Carillon. Consequently, three potential scenarios exist: Jean may have obtained leave, possibly after the battle phase of the campaign; he might have deserted, a risky and improbable choice; or he could have been absent at the time of the baptism, although this is unlikely as a father named on a baptism record is typically present, with any absence noted by the priest as "le père absent" on the record.

The lead-up to the pivotal French-English Battle of Québec took centre stage in 1759. Sensing the imminent arrival of the English invasion fleet, the French strategically shifted a substantial number of troops from Montréal to Québec in May, among them the regiments of Béarn and La Sarre. The English started their bombardment of Québec on June 12, unleashing a barrage from 60 artillery pieces. Jean likely played a role in the July 31 Battle of Beauport, also referred to as the Battle of Montmorency, which ended in a French victory and prompted the English to withdraw.

“A view of the fall of Montmorenci and the attack made by General Wolfe, on the French intrenchments near Beauport, with the Grenadiers of the army, July 31 1759,” engraving by William Elliott, after a drawing by Captain Hervey Smith, Wolfe’s aide-de-camp (Wikimedia Commons)

During the fateful Battle of the Plains of Abraham on September 13, 1759, the La Sarre Regiment played a prominent role as part of the French forces under the command of General Montcalm. Stationed on the right flank of Montcalm’s army, the regiment, along with others, stood against the formidable English troops led by General Wolfe. That day, Jean would have stood with his mates, all “5 pieds, 1 pouce” (“five feet, one inch”) of him, bearing his heavy flint lock muzzle-loader. The battle resulted in heavy casualties for both sides and ultimately ended in a French defeat. Tragically, Jean’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel M. de Sonnezergues, and many of his fellow regiment members were among the casualties. About 50 men from the La Sarre regiment were either killed or wounded. The battle marked a critical turning point in the conflict for control of Québec during the French and Indian War. The French army retreated overland to Jacques Cartier, a dozen leagues west of Québec. On September 18, the French officially surrendered Québec. The La Sarre regiment took refuge for its fourth winter at Île-Jesus.

Map depicting the troop arrangements at the 1759 Siege of Québec (Boston Public Library)

“A view of the taking of Quebec, 13th September 1759,” 1797 engraving based on a sketch made by Hervey Smyth, General Wolfe’s aide-de-camp (Library of the Canadian Department of National Defence)

Following the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759 and the subsequent British capture of Québec, the La Sarre Regiment, like many other French units, faced a challenging period. The defeat prompted a strategic retreat of French forces, and they sought refuge in their winter quarters in and around Montréal. During this time, the La Sarre Regiment, severely depleted in numbers due to the battle and the hardships of war, regrouped and attempted to recover.

In the months that followed, the regiment faced difficult siege conditions and had limited provisions. By March of 1760, the Second Battalion of the La Sarre Regiment had dwindled to only 430 men, with a significant portion deemed unfit for duty, and 51 soldiers were detached for service at Saint-Jean, a French fort southeast of Montréal.

Under the leadership of General Chevalier de Lévis, the remaining 345 soldiers of the La Sarre Regiment merged with 261 militiamen. They set sail from April 21 to April 25, followed by a march along the northern bank of the St. Lawrence River to Sainte-Foy, back where Wolfe’s forces ascended the Québec escarpment to victory the prior September. On April 28, the Battle of Sainte-Foy took place, where French forces, including the La Sarre Regiment, made a powerful stand against the English. Although the French emerged victorious at Sainte-Foy, they ultimately failed to capitalize on this success. The British received reinforcements and supplies, sealing the fate of the French forces in Canada. While the La Sarre Regiment and most other French troops retreated safely to Montréal, they could not stave off the inevitable. On September 9, 1760, New France capitulated to the British, marking the end of French rule in Canada.

“The Battle of Sainte-Foy,” watercolour by George B. Campion (Wikimedia Commons)

We don’t know whether Jean was at Saint-Jean or the Battle of Sainte-Foy, but he certainly wasn’t with the relicts of his battalion, the 243 men repatriated to France aboard British ships. Those vessels arrived with the La Sarre survivors in La Rochelle on December 3 and the depleted ranks of 130 men marched to Poitiers, arriving on December 11.

Several French troops remained in Canada or took up civilian lives, as was the case for Jean Poisson, who chose to stay in Canada and establish a family.

Family Life

With his military service over, Jean and Angélique initially settled in Pointe-Claire. The couple had seven children, two of whom were baptized in Sault-au-Récollet and the remainder in Pointe-Claire. Sadly, only one daughter lived to adulthood.

Children of Jean Poisson and Angélique Franche dite Laframboise:

The parish church of Sault-au-Récollet in 1749, drawing by Jean-Baptiste Lagacé (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Jean Baptiste was born on November 3, 1758, and was baptized the same day in Pointe-Claire. His godparents were Jean Marie Deforges and Marie Louise Bigras, his grandmother. Jean Baptiste died at the age of 6 on May 28, 1765. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire.

François Amable was born on March 15, 1762, and was baptized the next day in Sault-au-Récollet. His godparents were François Amable Leblanc and Ursule Laplante. François Amable was less than a year old when he died on January 25, 1763. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of La-Visitation-de-la-Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie in Sault-au-Récollet.

Marie Marguerite was born on October 16, 1763, and was baptized the same day in Sault-au-Récollet. Her godparents were Amable Robidou and Marie Guilbaut. Marie Marguerite was about 15 months old when she died on January 11, 1765. She was buried two days later in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire.

Angélique was born on June 23, 1765, and was baptized the same day in Pointe-Claire. Her godparents were Joachim Ladouceur and Marie Josèphe Mallet. Angélique is the only child of Jean and Angélique to live to adulthood and start a family of her own.

Marie Charlotte was born on February 1, 1767, and was baptized the next day in Pointe-Claire. Her godparents were Joachim Laframboise and Marie Charlotte Ladouceur. Marie Charlotte died at the age of 3 on October 27, 1770. She was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire.

Michel was born on November 13, 1768, and was baptized the next day in Pointe-Claire. His godparents were Michel [Létan?] and Catherine Lebeau. Michel was about 8 months old when he died on August 11, 1769. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire.

François was born on the morning of June 18, 1770, and was baptized the same day in Pointe-Claire. His godparents were François Pépin and Marie Josèphe Chénier..François was about 2 months old when he died on August 22, 1770. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire.

Baptism of Angélique Poisson in 1765 (Généalogie Québec)

As was customary at the time, causes of death were not specified in the burial records. The period in which Jean and Angélique had children was a treacherous one in regard to public health. In 1763, smallpox devastated Québec. In 1765, a non-identified epidemic also hit the colony.

Property

In the early 1760s, Jean and Angélique were involved in several land transactions. On May 18, 1761, the couple sold a plot of land in the parish of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul on Île-Jésus to ploughman Jean Étienne Wadens for 325 livres. The document indicates that Jean and Angélique were residents of the “côte Saint-Rémy dite des Sources” (on the island of Montréal). The land sold measured 3 arpents frontage by 40 arpents deep and included a house made of cedar posts. The land faced Rivière des Prairies at the Sault-au-Récollet and bordered the côte Saint-Ferréol.

On September 11, 1761, two agreements were drawn up by notary Gervais Hodiesne in Montréal. In the first, Jean and Angélique purchased half a plot of land in Sault-au-Récollet from Marie Josèphe Franche dite Laframboise (Angélique’s sister) and her husband François Poitevin dit Lafleur. This document indicates that Jean and Angélique were residents of côte Saint-Remy (on the island of Montréal). The land sold measured two perches and two feet frontage (facing the Rivière des Prairies) by thirty arpents deep. The sale also included any buildings constructed upon the land. In the second document, François and Marie Josèphe donated a sum of 1,000 livres to Jean and Angélique, in return for a lifetime annuity consisting of 12 minots of wheat and 15 cords of wood annually.

Two more agreements were penned by notaries in 1762, relating to real estate succession rights. On April 2, Jean and Angélique, residents of Sault-au-Récollet, sold their succession rights to land located on côte Saint-Rémy to Vincent Franche dit Laframboise, Angélique’s brother, for 300 livres. The sale involved half a piece of land measuring four arpents frontage, obtained from Angélique’s father’s estate. For the first time, we see Jean’s signature, albeit a little rudimentary, on a document.

Jean’s signature in 1762

On May 23, 1762, shoemaker Laurent Poitevin dit Lafleur sold his succession rights to a plot of land located in Sault-au-Récollet to Jean Poisson, residing in Sault-au-Récollet, for 100 livres. The sale involved a fourth of a plot of land measuring one and a half arpents frontage, adjoining Jean’s existing land.

In 1764, Jean and Angélique donated a portion of land in Sault-au-Récollet to Louis Boisme and his wife Françoise Joly. The donated land measured 18 perches and 4½ feet frontage (facing Rivière-des-Prairies) by about 40 arpents deep. It included a house made of “poteaux-en-terre” measuring 18 by 15 feet, covered in straw, with an earthen chimney and wood floors. The document specifies that this land comprised the lots that Jean and Angélique acquired on September 11, 1761, and on May 23, 1762. It appears that the couple donated this land because they were indebted to their landlords, owing them a total of 963 livres for the entirety of their 3-arpent land at Sault-au-Récollet. In exchange for the land donation, Boisme and Joly agree to pay the seigneurs of the Island of Montréal the sum of 601 livres, 7 sols and 6 deniers.

Money in New France

In New France, the main unit of currency was the livre. The livre was divided into 20 sols (called “sous” after 1715). Each sol was divided into 12 deniers. Livres were referenced by the symbol ₶.

Coin of Louis XIV for Canada, 5 sols, 1670 (photo by Jennifer McNair, Museums Victoria)

On July 18, 1765, Marie Louise Bigras, widow of André Frye dit Laframboise and Angélique’s mother, sold a plot of land located on the côte Saint-Rémy to her son-in-law Jean Poisson, a resident of côte Saint-Rémy. The land measured two arpents frontage by 28 arpents deep and was bordered by the Chemin du Roi (the King’s Road), the côte Saint-François, the land of Jean Sabourin and that of Charles Deslauriers. The sale included a small house and “half a barn,” which appeared to be located between the land sold and that of Deslauriers.

1765 Land Sale from Marie Louise Bigras to Jean Poisson (FamilySearch)

Fast forward to 1779, and we find Jean, Angélique and their 14-year-old daughter Angélique living in Pointe-Claire on the Island of Montréal. On July 27, a marriage contract was drawn up in Montréal between Angélique and Ignace Poiriau (or Perriault) dit Bellefeuille, a 22-year-old resident of Lachine. Jean was present to speak on his minor daughter’s behalf and to consent to the marriage. The groom gave his bride the sum of 300 old chelins as a dower. The preciput was established at 150 old chelins. [The preciput, under the regime of community of property between spouses, was an advantage conferred by the marriage contract on one of the spouses, generally on the survivor, and consisting in the right to levy, upon dissolution of the community, on the common mass and before any partition thereof, some of which specified property or a sum of money.]

Legal Age to Marry & Age of Majority

In order to marry in the time of New France, a groom had to be at least 14 years old, while a bride had to be at least 12. In the era of Lower Canada and Canada-East, the same requirements were in place. The Catholic church revised its code of canon law in 1917, making the minimum age of marriage 16 for men and 14 for women. In 1980, the Code civil du Québec raised the minimum age to 18 for both sexes. Furthermore, minors needed parental consent in order to marry. In New France, the age of legal majority was 25. Under the British Regime, it was changed to 21. Since 1972, the age of majority in Canada has been set at 18 years old.

On the very same day, Jean and Angélique donated two plots of land to the future married couple. One was located on côte Saint-Rémy, in the parish of Pointe-Claire. It measured three arpents frontage by 29 arpents deep and faced the Chemin du Roi (the King’s Road). The land included a wooden house, a barn and a stable. The other plot was located in the parish of Saint-Eustache on the banks of the du Chêne River. Jean and Angélique also donated two oxen, two bulls, three cows, two horses, five sheep, four pigs, a dozen chickens, one rooster, as well as farming tools and equipment. In exchange, the newly married couple would be responsible for the land’s rent (“cens et rentes”) and any outstanding debts. They would also provide Jean and Angélique a lifetime pension, paid annually until their deaths, including:

30 minots of wheat

150 pounds of “good fatty lard” (to be delivered each Christmas)

150 pounds of beef (to be delivered each Christmas)

8 jugs of “eau de vie” (brandy) (to be delivered each Christmas)

20 cords of “good” wood (half to be delivered at Christmas and half in March)

12 pounds of soap

12 pounds of candles

The pension would be halved if either Jean or Angélique died. Portions of the 12-page document are difficult to read because of bleeding ink, but these agreements normally also include provisions for the parents to be housed, fed and otherwise taken care of until their deaths, and their burials paid for.

Angélique and Ignace settled in Pointe-Claire, then moved to Oka, and eventually to Saint-André-d’Argenteuil, across the river from Rigaud (where they were parishioners). They had 14 children, six of whom were married and had their own families. Per their donation agreement, Angélique’s parents likely moved with them (or at least nearby).

In 1803, Jean and Angélique, residents of the bay of Argenteuil, exchanged plots of land with Joachim Poiriau and Marie Anne Beaupré, his wife (Joachim was Ignace’s brother). The lands were located in the “bay of Carillon, seigneurie of Argenteuil.”

The End of an Era

Burial of Jean Poisson in 1805 (Généalogie Québec)

Jean Poisson died at the age of about 77 on October 17, 1805. He was buried two days later in the parish of Sainte-Madeleine in Rigaud. He was recorded as a “former farmer in the seigneurie of Argenteuil.” His son-in-law Ignace and nephew Jacques Franche attended the burial. And so passed the Lorraine soldier, who fifty years earlier cut a fine figure in his La Sarre uniform. Picture his white justaucorps with blue turnback cuffs and three buttons, red jacket, pale grey stockings and breeches, black metal-buckle shoes, white gaiters, and black felt tricorn hat. At five feet one inch, he was almost as tall as his rifle was long.

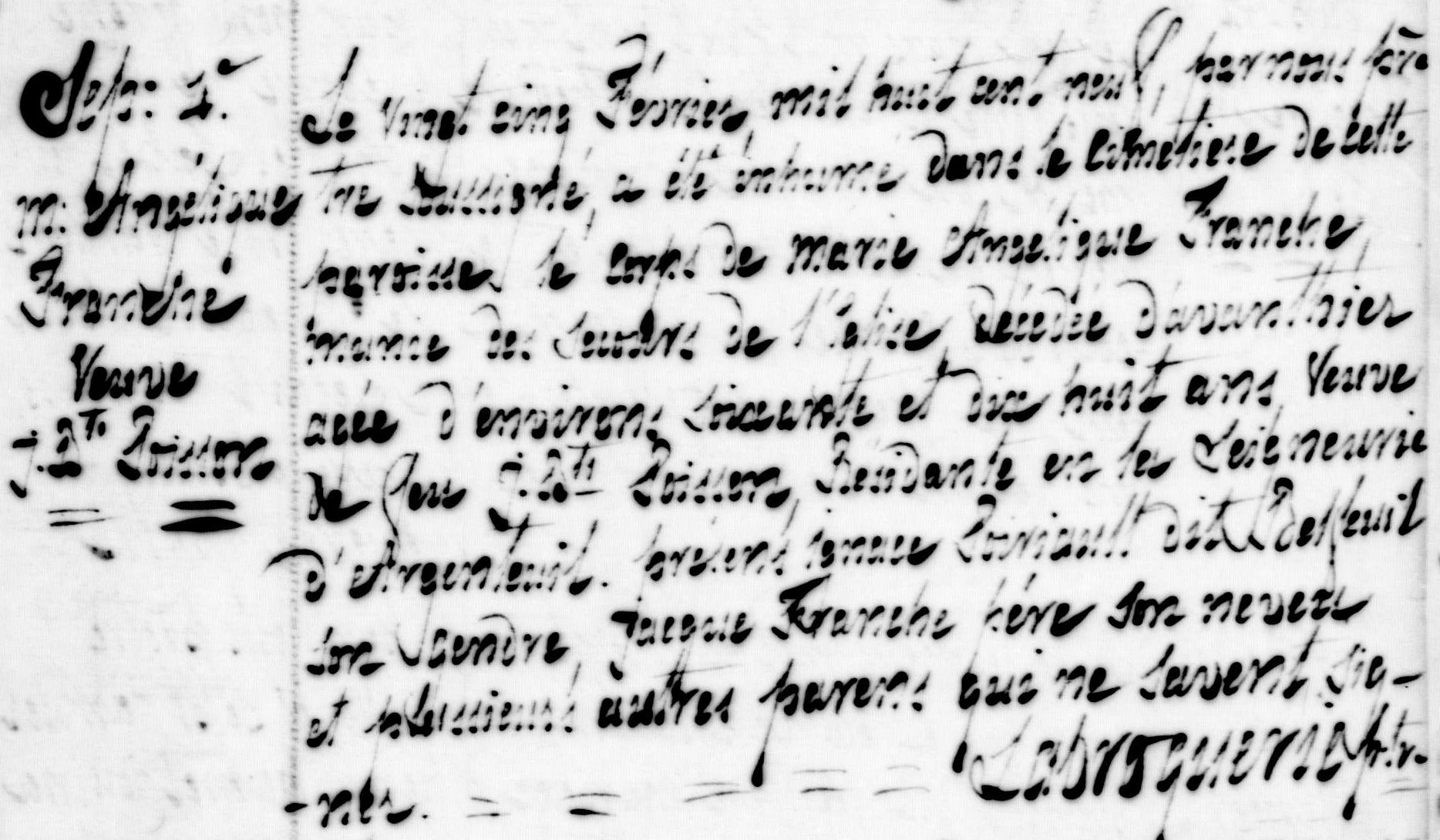

Burial of Angélique Franche dite Laframboise in 1809 (Généalogie Québec)

Angélique Franche dite Laframboise died at the age of 75 on February 23, 1809. She was buried two days later, also in the parish of Sainte-Madeleine in Rigaud. She was recorded as the “widow of Jean Baptiste Poisson, resident in the seigneurie of Argenteuil.” The same witnesses were present at her burial: son-in-law Ignace and nephew Jacques Franche “and many other relatives.”

Saint-André-d’Argenteuil in 1850 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec). Saint-André was called St. Andrews by its anglophone residents.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources & further reading:

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/recherche?numero=243352), entry for Jean-Baptiste POISSON/POIRSON (person #243352), updated on 22 Aug 2015.

"Jean Poirson," database of the 1759-1760 soldiers, Plaines d’Abraham, Government of Canada, The National Battlefields Commission (https://www.ccbn-nbc.gc.ca/fr/histoire-patrimoine/batailles-1759-1760/details-soldat/?id=14302&page=1&qs=%26termes%3Djean%2Bpoisson%26type%3Dsimple).

Pierre Héliot, "La Campagne du régiment de la Sarre au Canada (1756-1760)," Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 1950, 3(4), 518–536, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/801595ar).

“Siege of Québec: Opposing Forces,” Plaines d’Abraham, Government of Canada, The National Battlefields Commission (http://bataille.ccbn-nbc.gc.ca/en/siege-de-quebec/forces-en-presence/armee-francaise-canadiens-amerindiens/troupes-de-terre-troupes-regulieres.php), citing original data: Jack L. Summers and René Chartrand, Military Uniforms in Canada 1665-1970 (National Museum of Man, Ottawa, 1981), p. 36, and René Chartrand, Quebec 1759: The Battle that Won Canada (Bloomsbury USA, 1999), p. 23.

André Lachance, Vivre, aimer et mourir en Nouvelle-France; Juger et punir en Nouvelle-France: la vie quotidienne aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Montréal, Québec: Éditions Libre Expression, 2004), 91, 124-128.

"Contrat de mariage et questions de préséance en Nouvelle-France", Histoire du Québec (https://histoire-du-quebec.ca/contrats-de-mariage/); citing original information from Pierre-Georges Roy, Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, 1929.

“Actes de notaire, 1734-1767: Charles-François Coron," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C375-6SQJ-9?i=921&cat=481208), land concession to Jean Poirson, 9 Nov 1757, images 922 to 925 of 3200, film 1420431, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1740-1764: Gervais Hodiesne," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5X-V9TV?i=559&cat=481473), marriage contract of Jean Poirson and Angélique Franche dite Laframboise, 18 Nov 1757, images 560 to 563 of 3153, film 1432362, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1737-1778 : François Simonet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-W7C9-Z?i=2005&cat=529340), land sale by Jean Poireson and Angélique Franche dit Laframboise to Jean-Étienne Wadens, 18 May 1761, images 2006 to 2008 of 3120, film 1464535, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1740-1764: Gervais Hodiesne," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5X-N9XX-2?i=2594&cat=481473), sale of a portion of land between François Poitevin dit Lafleur and Marie Josèphe Franche dite Laframboise, and Jean Poirson and Angélique Franche dite Laframboise, 11 Sep 1761, images 2595 and 2696 of 2965, film 1432363.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5X-N9XF-B?i=2596&cat=481473), donation from François Poitevin dit Lafleur and Marie Josèphe Franche dite Laframboise to Jean Poirson and Angélique Franche dite Laframboise, 11 Sep 1761, images 2597 to 2699 of 2965, film 1432363.

“Actes de notaire, 1737-1778 : François Simonet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-W7XN-M?i=3044&cat=529340), sale of real estate succession rights by Jean Poirson and Angélique Franche dit Lafranboise to Vincent France dit Lafranboise, 2 Apr 1762, images 3045 to 3047 of 3120, film 1464535.

“Actes de notaire, 1740-1764: Gervais Hodiesne," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTS-C31P-Q?i=521&cat=481473), sale of real estate succession rights by Laurent Poitevin dit Lafleur to Jean Baptiste Poirson, 23 May 1762, images 522 to 523 of 3117, film 1432364.

“Actes de notaire, 1740-1764: Gervais Hodiesne," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTS-CQMC-R?i=2664&cat=481473), donation of land from Jean Baptiste Poirson and Angélique Frenche to Louis Boimier and Françoise Jolie, 17 Jan 1764, images 2665 to 2667 of 3117, film 1432364.

“Actes de notaire, 1737-1778 : François Simonet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-4SVG-Y?i=3006&cat=529340), sale land by Marie-Louise Bigras, widow of André Franche dit Lafranboise, to her son-in-law Jean-Baptiste Poirson, 18 Jul 1765, image 3007 of 3212, film 1464536.

“Actes de notaire, 1764-1786: Simon Sanguinet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-4SVD-1?i=2750&cat=672701), marriage contract of Ignace Poiriau dit Bellefeuille and Angélique Poirson, 27 Sep 1779, images 2751 to 2754 of 3202, film 1487600, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-4S82-N?i=2754&cat=672701), land donation from Jean-Baptiste Poirson and Angélique France dit Laframboize, to Ignace Poireau dit Bellefeuille and Angélique Poirson, 27 Sep 1779, images 2755 to 2766 of 3202, film 1487600.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (www.Archiv-Histo.com), "Echange de terres situées en la baie de Carillon, seigneurie d'Argenteuil entre Joachim Poiriaux, cultivateur, et Marie-Anne Beaupré, son épouse, de la paroisse de Lachine, île et comté de Montreal, et Jean-Baptiste Poisson, cultivateur, et Angélique Franche dit Laframboise, son épouse, de la baie d'Argenteuil," 25 Jul 1803, notary L. Thibodeau.

"Québec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968,” digital image, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_11040989?pId=14617437), marriage of Jean Poisson and Angélique Frey, 20 Nov 1757, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim); citing original data: Drouin Collection, Institut Généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

"Fonds Ministère des Terres et Forêts - Archives nationales à Québec," digital image, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/258504), “Plan de la province de Québec," between 1765 and 1770, reference E21,S555,SS1,SSS8,P11, ID 258504.

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1750/1758/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/277513), baptism of Jean Baptiste Poisson, 3 Nov 1758, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/278516), burial of Jean Baptiste Poisson, 29 May 1765, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/Mtl/Catholique/Montréal, Sault-au-Récollet) (La Visitation-de-la-Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie)/1760/1763," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/273882), baptism of François Amable Poisson, 16 Mar 1762, Sault-au-Récollet (La Visitation-de-la-Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

[1] Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/274581), burial of François Amable Poirson, 26 Jan 1763, Sault-au-Récollet (La Visitation-de-la-Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie).

[1] Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/273961), baptism of Marie Marguerite Poisson, 16 Oct 1763, Sault-au-Récollet (La Visitation-de-la-Bienheureuse-Vierge-Marie).

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1760/1765/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/278485), burial of Marie Poisson, 13 Jan 1765, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/277859), baptism of Angelique Poisson, 23 Jun 1765, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim).

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1760/1767/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/652587), baptism of Marie Charlotte Poisson, 2 Feb 1767, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1770/1770/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/500187), burial of Marie Charlotte Poisson, 28 Oct 1770, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1760/1768/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/652716), baptism of Michel Poisson, 14 Nov 1768, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1760/1769/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/500122), burial of Michel Poirson, 12 Aug 1769, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

"Québec/Fonds Drouin/P/Pointe-Claire/Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim)/1770/1770/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/652855), baptism of François Poisson, 18 Jun 1770, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/500174), burial of François Poisson, 23 Aug 1770, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim).

“Québec/Fonds Drouin/R/Rigaud/Rigaud (Ste-Madeleine)/1800/1805/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/2681558), burial of Jean Baptiste Poisson, 19 Oct 1805, Rigaud (Ste-Madeline), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.

“Québec/Fonds Drouin/R/Rigaud/Rigaud (Ste-Madeleine)/1800/1809/," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/img/acte/2681662), burial of Marie Angélique Franche, 25 Feb 1809, Rigaud (Ste-Madeline), citing original data: Fonds Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin, Montréal.