Compagnies franches de la marine

Many groups of immigrants that landed on Canadian soil in the 17th century are well-known and well-studied: the Filles du roi, the Filles à marier and the soldiers of the Carignan-Salières regiment, to name a few. Most of us with French-Canadian roots will often come across another group of soldiers that was stationed in New France for much longer: the Compagnies franches de la Marine. Given their 77-year history, it is surprising that they remain relatively unknown. This is their story.

The Compagnies franches de la Marine

1683-1760

Many groups of immigrants that landed on Canadian soil in the 17th century are well-known and well-studied: the Filles du roi (1663-1673), the Filles à marier (1634-1662) and the soldiers of the Carignan-Salières regiment (1665-1668), to name a few. Most of us with French-Canadian roots will often come across another group of soldiers that was stationed in New France for much longer: the Compagnies franches de la Marine. Given their 77-year history, it is surprising that they remain relatively unknown. One possible reason is the anonymity of the soldiers. While the lives of the officers are well-documented, there exists no list or roll naming the soldiers under their command.

The Evolution of a Name

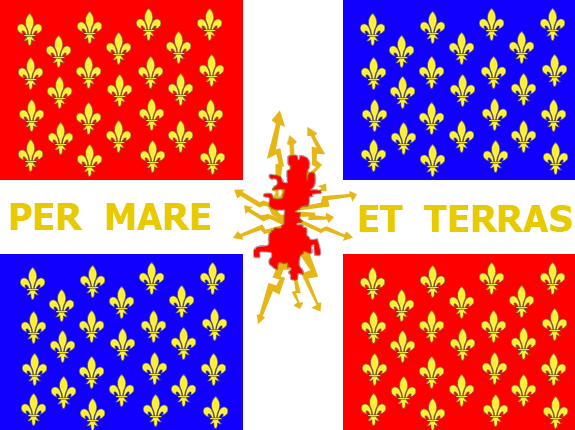

Flag of the Compagnies franches de la Marine, Wikimedia Commons

Tracing their history back to 1622, the predecessors of the Compagnies franches de la Marine were groups of soldiers stationed on the ships of the French navy, called "compagnies ordinaires de la mer." In 1674, Secretary of State of the Navy Jean-Baptiste Colbert renamed them "Troupes de la Marine." In 1690, they were called "Compagnies franches de la Marine." Despite their name and association with the Ministry of the Navy, the companies sent overseas were not navy troops, but colonial army troops. The term "franches" (independent) refers to the fact that the troops were not organized in regiments.

A Plea for Help

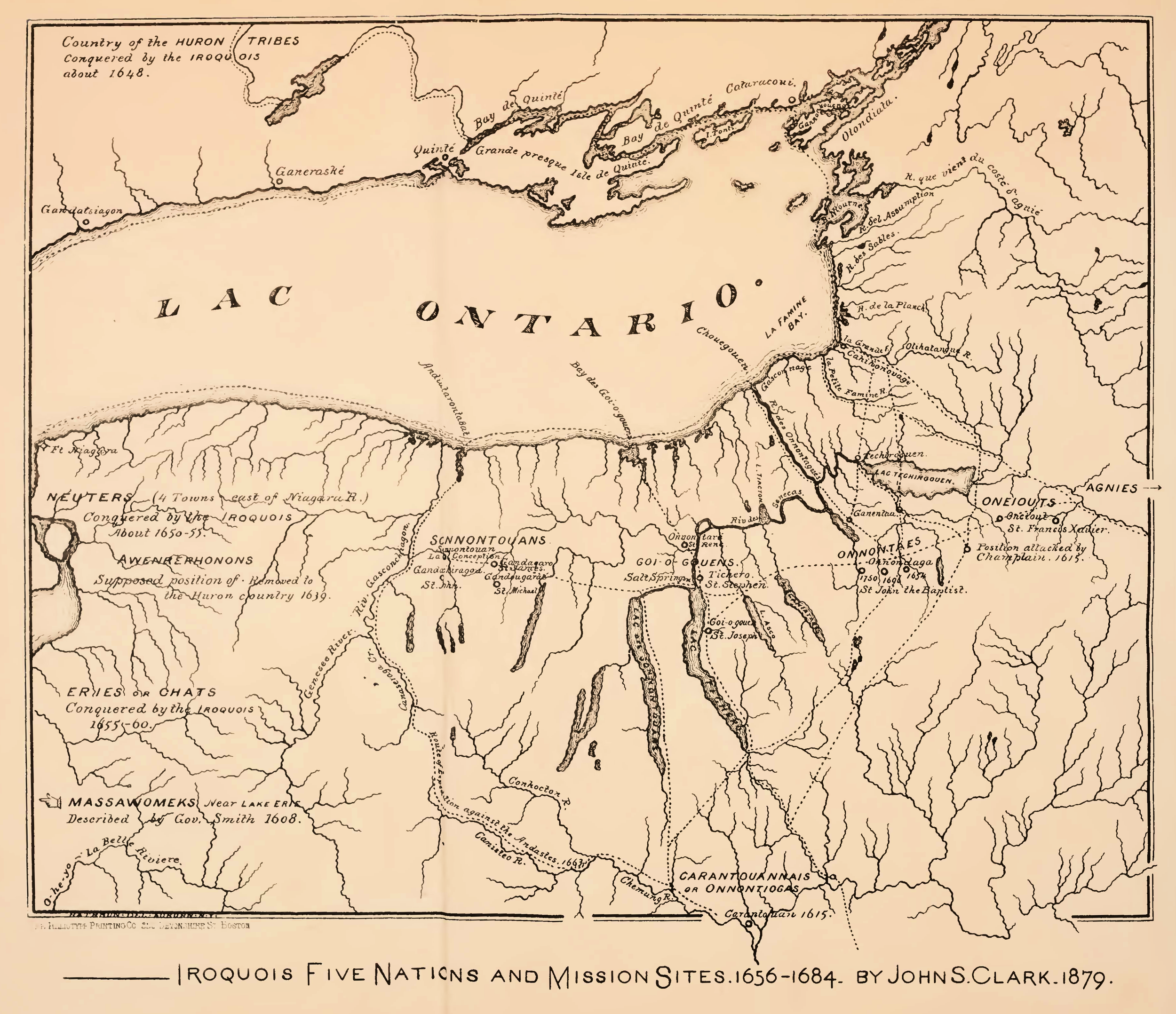

The French Navy was responsible for the defense of France's colonies, including New France. In the latter half of the 17th century, New France faced constant threats from its enemies, especially the Iroquois, who were allied with the English. In order to defend the young colony, King Louis XIV ordered the construction of garrisons and the recruitment of local militia soldiers. Despite these efforts, Iroquois attacks continued. In 1665, about 1,200 men from the Carignan-Salières regiment were sent to New France to neutralize the Iroquois threat. The soldiers remained until 1668, as a fragile peace returned to the colony.

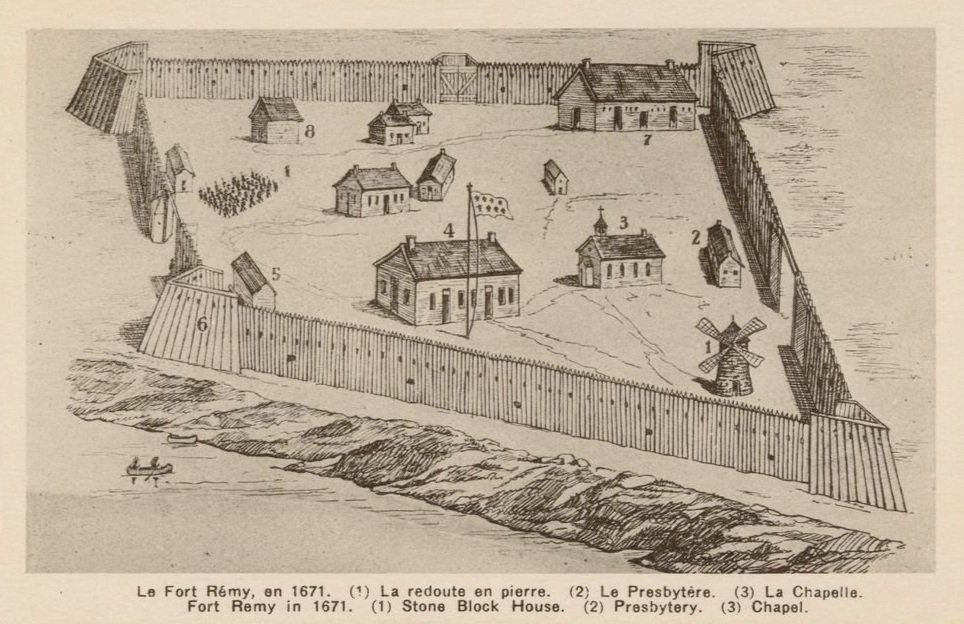

“Fort Remy in 1671" (Lachine), Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

The 1670s and early 1680s saw a resurgence in Iroquois hostilities and attacks on French colonists. Governor General Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre sent an urgent message to France, asking for reinforcements. In November of 1683, the ship La Tempête arrived in New France carrying 130 soldiers from three companies of the Compagnies franches de la Marine. (Of the 150 men who departed France, only 130 arrived in Canada, the rest succumbing to scurvy during the voyage.) Their primary objectives were defending the colony from the Iroquois and protecting her interests in the lucrative fur trade.

"Map of Iroquois Five Nations and Mission Sites 1656-1684" by John S. Clark, 1879. Wikimedia Commons.

A New Canadian Force

From 1683 to 1688, 35 companies were sent to Canada. For a young colony with a population of about 10,300, there were 1,418 soldiers stationed there to protect them. As the soldiers' numbers decreased due to death and permanent settlement in New France, the number of companies was reduced to 28 in 1689. This number remained in place until the Seven Years War. These troops essentially became the colony's permanent "Canadian" forces. At first, they were composed almost entirely of French soldiers. Between 1683 and 1715, between 3,000 and 3,500 soldiers were serving in New France. About 98% were born in France and about 42% came from a 150 km radius from Rochefort.

This wasn't the case for officers, however. In 1683, all officers in New France were French. By 1690, a quarter were Canadian born. By the 1720s, this number rose to about half and finally reached three quarters by the 1750s. This became known as the "canadianization" of the troops. These Canadian officers were appointed from upper-class or noble families.

Fort de la montagne, built in 1685. "Fort 'de la Montagne' was just a few hundred metres outside of Montreal on the flanks of Mount Royal as it appeared in about 1690. It featured, A: chapel of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges; B: mission priests house; C: turrets also used as a school by the sisters of the Congrégation; D: barn also to be used as a shelter by women and children during attacks; E: turrets; F: Indian village. The turrets indicated in ‘C’ can still be seen today." (Historical information from Canadian Military History Gateway; image from Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec).

"Compagnies franches de la Marine – 1695," painting by A. d' Auriac, 1932, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Troop Composition

The Companies took their orders from the Governor General, who was in charge of the colony's military affairs. Each company was composed of up to 50 soldiers and headed by a captain, who gave the company its name (for example, the Compagnie de Duplessis, or the Compagnie de Contrecoeur). The company included a lieutenant, as well as an ensign (a post created in 1687; another was added in 1722). Under their command were two sergeants, three corporals, two drummers and up to 39 soldiers (though this was supposed to be the composition of each company, in reality many were rarely complete). Cadets were officially added to the ranks in 1731 and paid 10 sols per day. Soldiers were paid 9 livres per month, while corporals made 14 livres, sergeants 20, ensigns 30 to 40, lieutenants 60 and the captain was paid 90 livres per month.

"Soldier of the Compagnies franches de la Marine in New France, circa 1740. This man of the Compagnies franches de la Marine wears the grey-white coat of France with the blue facings of the Troupes de la Marine. He is armed with a musket, sword and bayonet. This is how the men of the Compagnies franches would appear on parade or in garrison in one of the larger forts. Reconstruction by Michel Pétard". Canadian Military History Gateway.

“Drummer of the Compagnies franches de la Marine in New France, 1716-1730. This drummer in the livery of the King of France belongs to the Compagnies franches de la Marine in New France. The soldier's clothing style dates him between 1716 and 1730. Reconstruction by Michel Pétard. Canadian Military History Gateway.

"Sergeant of the Compagnies franches de la Marine of Canada, 1701-1716. This man wears a grey-white uniform with a red lining and red stockings (particular to sergeants of the Compagnies franches de la Marine at this time). The silver lace on his cuffs is also a distinguishing mark of a sergeant. He carries a halbard, the distinctive weapon of sergeants in European armies. Reconstruction by Michel Pétard". Canadian Military History Gateway.

In New France, the Compagnies franches de la Marine were spread out between the governments of Québec, Montréal and Trois-Rivières, as well as the Pays d'en Haut (the territories to the west of Montréal, the Great Lakes and Ohio). The soldiers didn't live in military barracks (these weren't established until 1749); they lived with local families. Unless they were called for military duty, soldiers lived a normal civilian life and worked to earn extra money.

Most of the French soldiers that were recruited for service in New France came from modest backgrounds. Most were farmers, although some were skilled tradesmen. The French authorities wanted recruits who could continue their previous occupations in New France after their military service, helping to grow the colony.

Iroquois Warrior, from Encyclopedie Des Voyages, engraved by J. Laroque, 1796. Wikimedia Commons.

Battles & Raids

For the first French soldiers engaged in conflict against the Iroquois, it became apparent that European-style war tactics weren't going to be effective in New France, largely due to a lack of infrastructure, a vast territory and harsh Canadian winters. The Canadian-born soldiers were familiar with indigenous methods of warfare, and alongside European discipline, these soon became the only viable tactics to fight the Iroquois. Gone were the days of marching side by side to the sounds of a drum. Soldiers in Canada had to catch their enemies by surprise and retreat quickly, most often in forest settings. Captains also believed in diversifying their troops: they fought alongside the Canadian militia, voyageurs who knew the terrain, and their indigenous allies. Supplies were kept to a strict minimum: only food, weapons (guns, hatchets and knives) and tools were taken. They travelled on foot and by canoe or sled, storing food caches along the way for the return journey.

Soldiers were given rations to eat, with food being sourced by their officers. A sample inventory from 1748 records that officers received wine, brandy, olive oil, vinegar, butter, pepper, spices, peas, ham, beef, bread and molasses.

The troops travelled as far as Fort Frontenac (present-day Kingston, Ontario), Hudson's Bay and Michilimackinac (between Lakes Superior and Michigan) in an effort to control the fur trade. They also guarded forts and went on regular patrols. Soldiers from the Compagnies franches de la Marine were also involved in raids in New England, in response to the "Lachine Massacre" of 1689. They burned and destroyed Schenectady (New York), Salmon River (near Portsmouth, Massachusetts) and Casco (Maine). They conducted raids on Deerfield and Haverhill, Massachusetts, taking men, women and children as prisoners back to Canada.

Copy of the 1701 Peace Treaty including pictograms of 32 of the signatory nations. Wikimedia Commons.

The Iroquois threat came to an end with the 1701 Grande Paix de Montréal (the Great Peace of Montreal). Near the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713, eight new companies were created to defend l'Île-Royale (present-day Cape Breton and Prince Edward Island). Even more companies were sent to Louisiana, a district of New France: 14 companies in 1718 and 24 companies in 1743. Other companies were sent to the French Caribbean.

Fortifying the French Presence

During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), troops were tasked with repairing existing forts, and the garrisons of Fort Saint-Frédéric (on Lake Champlain), Fort Niagara (on the Niagara River, present-day New York) and Fort Frontenac (on the St. Lawrence River, present-day Kingston) were expanded. Patrols were established along the shores of Lake Champlain and artillery platforms were raised at Québec City, facing the St. Lawrence. A system of signals was established along the river to raise an alarm as needed. The governor also ordered more raids against the English on border towns in Nova Scotia (Grand-Pré) and New England (Saratoga, Fort Massachusetts and Charlestown).

"Fort Niagara, 1728," painting by Charny. Wikimedia Commons.

Fort Saint-Jean on Richelieu River in Canada during the 1750s. Wikimedia Commons.

In the years following the end of the war, the French consolidated their presence in the Lake Champlain region, as well as the Great Lakes region and along the St. Lawrence west of Montreal. More forts were constructed: Fort St-Jean (on the Richelieu River), Fort de la Présentation (Ogdensburg), Fort de Rouillé (Toronto) and Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh). Settlement was encouraged in all of these areas.

Seven Years War (The French and Indian War)

In the lead-up to the Seven Years War (1756-1763), both France and England rushed to arm themselves and bolster their troop numbers. At the start of the war, France had over 8,000 overseas marine infantrymen. In New France, the number of companies from the Compagnies franches de la Marine went from 28 to 40. In the fall of 1757, approximately 2,300 of these military men were in Canada.

Alongside militia soldiers and indigenous allies, the troops defended New France from the British, and also organized its own attacks on British forts. They participated in the Battle of Fort Necessity, the defeat of General Braddock and the defense of Fort Beauséjour, the Battle of Lake George, the Battle of Fort Oswego, the siege and capture of Fort William-Henry, the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the siege of Québec. Among the deadliest battles for the Compagnies franches de la Marine were the Battle of Sainte-Foy and the Battle of Belle-Famille.

« The Battle of Sainte-Foy », oil painting by Joseph Légaré, circa 1854. National Gallery of Canada.

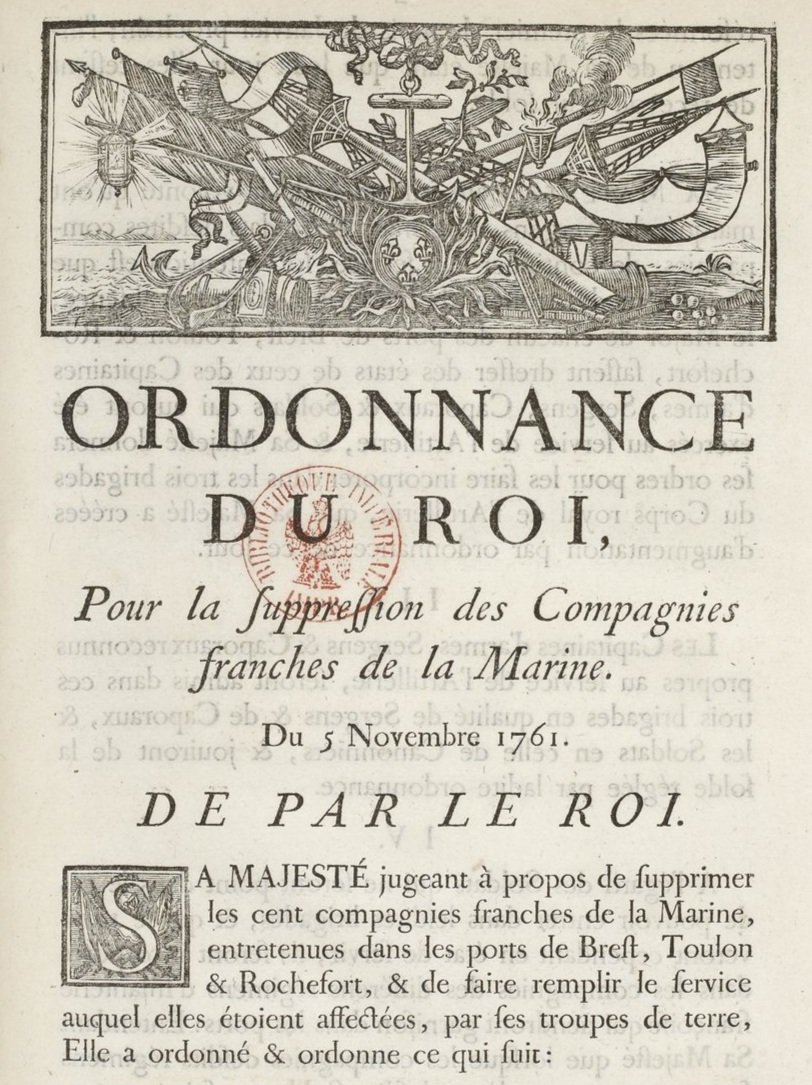

The surrender of Montreal on 8 Sep of 1760 marked the end of the Compagnies franches de la Marine in Canada. After the defeat of New France by the British, approximately 2,600 soldiers from the Compagnies franches de la Marine were in Canada and Acadia (Louisbourg). At least 600 soldiers chose to stay permanently, while the remainder returned home to France. The majority of officers left Canada. By 1761, 177 had gone, while only about 15 officers remained.

The Compagnies franches de la Marine themselves were officially abolished in 1761.

Order of King Louis XIV for the abolishment of the Compagnies franches de la Marine, 5 Nov 1761. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Historical re-enactors of the Compagnie Franche de la Marine during the celebrations of the 400th anniversary of Quebec City, photo by Harfang, Wikimedia Commons.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Arnaud Balvay, "Les hommes des troupes de la marine en Nouvelle-France (1683-1763)", La Commission franco-québécoise sur les lieux de mémoire communs (CFQLMC) (https://www.cfqlmc.org/bulletin-memoires-vives/bulletins-anterieurs/bulletin-n-22-octobre-2007/les-hommes-des-troupes-de-la-marine-en-nouvelle-france-1683-1763).

Government of Canada, "The Compagnies Franches de la Marine of Canada," Canadian Military History Gateway (http://www.cmhg.gc.ca/cmh-pmc/page-64-eng.aspx.

Marcel Fournier (dir.), Les Officiers des troupes de la marine au Canada, 1683-1760 (Québec, Septentrion, 2017).

André Sévigny, "Le soldat des troupes de la marine (1683-1715) : premiers jalons sur la route d'une histoire inédite," Les Cahiers des dix, (44), 39–74, 1989 (https://doi.org/10.7202/1015556ar).

Stuart R.J. Sutherland, "Troupes de la Marine," Historica Canada (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/fr/article/troupes-de-la-marine), published 7 Feb 2006; updated 14 Jan 2021.

Claude Villeneuve, "Historique des Compagnies Franches de la Marines," Manuel de la Garnison de Québec (http://www.lagarnisondequebec.com/historique.html).