Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy & Jeanne Denault

Discover the story of Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy— a soldier of the Carignan-Salières Regiment from Saint-Martin-des-Pézerits (Orne, Perche)—and Jeanne Denault/Denot, a Fille du roi from Paris. Married in 1678 at La Prairie near Montréal, they settled in Saint-Lambert, founding the Surprenant family line in New France whose descendants spread across Québec and North America.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy & Jeanne Denault

From Soldier and Fille du roi to Settlers in New France

Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy, son of Jacques Surprenant and Louise Roquet, was born around 1645 in Saint-Martin, Perche, France. According to the PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique), this location corresponds to the present-day rural commune of Saint-Martin-des-Pézerits, located within the département of Orne. Its current population is around 120 inhabitants.

On Canadian documents, Jacques’s name appears as Supernan, Supernant and Supernon.

Location of Saint-Martin-des-Pézerits in France (Mapcarta)

The church of Saint-Martin, where Jacques was likely baptized, probably dates to the early 12th century: its Romanesque fabric includes flint and grison/roussard stone around the west portal and a band at mid-apse. In the 17th century the nave was widened to the south, paired (geminated) windows were added, and a timber octagonal bell-tower with a slate spire was built. A south sacristy and a brick relieving arch at the portal were later 19th-century additions. After structural issues—especially in the bell-tower base—fundraising began in 2019. Restoration work started in 2021, and the church was inaugurated at the end of that year.

The church of Saint-Martin-des-Pézerits (photo by Brunodumaine, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Growing up in Saint-Martin-des-Pézerits meant living in a small, scattered parish where mixed farming prevailed. Rye, oats, and garden plots were cultivated, with a cow or two, pigs, and poultry providing subsistence. Very typically for the area, hemp patches were processed at home into cordage and coarse textiles, providing a vital side income during winter months. Parish life centred on the church—already old by the seventeenth century and periodically altered as the community’s needs and means allowed.

Households were subject to overlapping dues: tithes to the church and seigneurial obligations, along with the crown’s indirect taxes—notably the salt tax (gabelle), which weighed unevenly across provinces and fuelled petty smuggling and resentment. These pressures intensified during the political turbulence of the Fronde (1648–1653), when fiscal exactions and insecurity affected much of France. For a younger son facing limited land and modest prospects, military service may have seemed both a duty and an opportunity.

A Soldier's Path to New France

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (October 2025)

Likely in his late teens, Jacques enlisted to serve in the Carignan-Salières Regiment. Service offered steady pay, clothing, and food; critically, the Crown and colonial officials encouraged soldiers to remain as settlers with land grants and marriage incentives once the campaigns ended (roughly 400 remained). For someone from a tiny parish in Orne, the prospect of land and advancement after discharge was a powerful reason to enlist and sail.

Jacques served in the Contrecœur Company. He arrived with his fellow soldiers in New France in August of 1665.

Military Activities of the Compagnie de Contrecœur

Almost immediately after arriving at Québec, Contrecœur’s soldiers were sent up the Richelieu River to join the regiment’s fortification efforts on the Iroquois frontier. Over the late summer and fall of 1665, the Carignan-Salières troops rapidly constructed a chain of forts along the Richelieu. This work included rebuilding Fort Richelieu (at Sorel) on the old 1642 site to guard the river’s mouth, under the direction of Captain Pierre de Saurel. Further upriver, they built Fort Saint-Louis at Chambly and Fort Sainte-Thérèse. Contrecœur’s company assisted in this fort-building campaign – some of its men likely helped garrison or supply the new posts. After initial construction duties, the Contrecœur Company travelled upriver to camp at Montréal for the winter of 1665–66.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (October 2025)

In early 1666, Contrecœur’s company likely participated in Governor Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles’s ill-fated winter expedition against the Mohawk (Agniers) nation. Courcelles commanded approximately 500 French regulars and Canadian militia southward in deep winter, aiming for a surprise attack on Mohawk villages. The march was disastrous: a combination of blizzards, unfamiliarity with snowshoes, and the absence of expected Indigenous guides led the French off-course in metre-deep snow. Many soldiers suffered severe frostbite; “dozens of ill-prepared men” died from cold and hunger. Near Schenectady (then an English/Dutch outpost), Mohawk warriors ambushed a French detachment, killing one officer and six of his men. Courcelles’s starving, exhausted troops never reached the Mohawk towns – the governor ordered a retreat in February after realizing they were trespassing on English territory. Harassed by Mohawk parties on the retreat, over 60 French soldiers perished before the survivors straggled home to Québec in March. Although this mid-winter campaign failed to engage the enemy, it marked the first time French forces had advanced so far into Iroquois country. The heavy losses also taught New France’s leaders a hard lesson: “not [to] launch military campaigns in the middle of winter” in the future.

Map by R. A. Nonenmacher (Wikimedia Commons)

In September 1666, the full Carignan-Salières Regiment, including the Contrecœur Company, advanced into Mohawk territory under Lieutenant-General Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy. The expedition comprised roughly 1,300 men—regulars, Canadian militia, and Indigenous allies. After extensive preparations and supply movements along the Richelieu River, the army assembled at Fort Sainte-Anne on Isle La Motte before marching south into present-day New York.

The French advanced in three divisions. Governor Courcelles led the vanguard, Tracy commanded the main force, and Captains Chambly and Berthier brought up the rear. On October 3, the troops set out through the Mohawk Valley, meeting little resistance. The Mohawk warriors withdrew into the forests, abandoning their fortified towns. Tracy ordered the destruction of all four Mohawk villages and their food supplies. At Tionnontoguen, the army raised a cross and the royal arms of France, symbolically claiming the territory for King Louis XIV.

After this campaign of devastation, the regiment marched north in worsening weather. Several soldiers drowned or died of exhaustion, but most reached Québec safely in November 1666. Jesuit observers recorded that the French had burned the Mohawk villages “with all the corn,” reducing the population to famine conditions. Intendant Jean Talon reported that the destruction of food and shelter would break their resistance. Facing starvation, the Mohawks sought peace, and by the summer of 1667, envoys from all Five Nations met at Québec to conclude a treaty that brought an end to the long Franco-Iroquois conflict.

Aftermath

Following the campaign, the Contrecœur Company was stationed around Montréal and the Richelieu valley, maintaining peace and security along the frontier. Their presence deterred renewed Iroquois attacks. French authorities upheld strict discipline: when three French soldiers murdered a Seneca chief in 1669, Governor Courcelles had them publicly executed before Iroquois witnesses to preserve trust between the two nations.

By 1668, the regiment’s mission was complete. The majority of the regiment was recalled to France, but roughly 400 soldiers and officers remained in New France. Captain Antoine Pécaudy de Contrecœur settled permanently, receiving a seigneurie along the St. Lawrence in 1672. Most of his men also stayed, establishing themselves as settlers near Montréal.

A New Home in New France

Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy was one of the soldiers who chose to stay in New France. He first settled in Longueuil, east of Montréal.

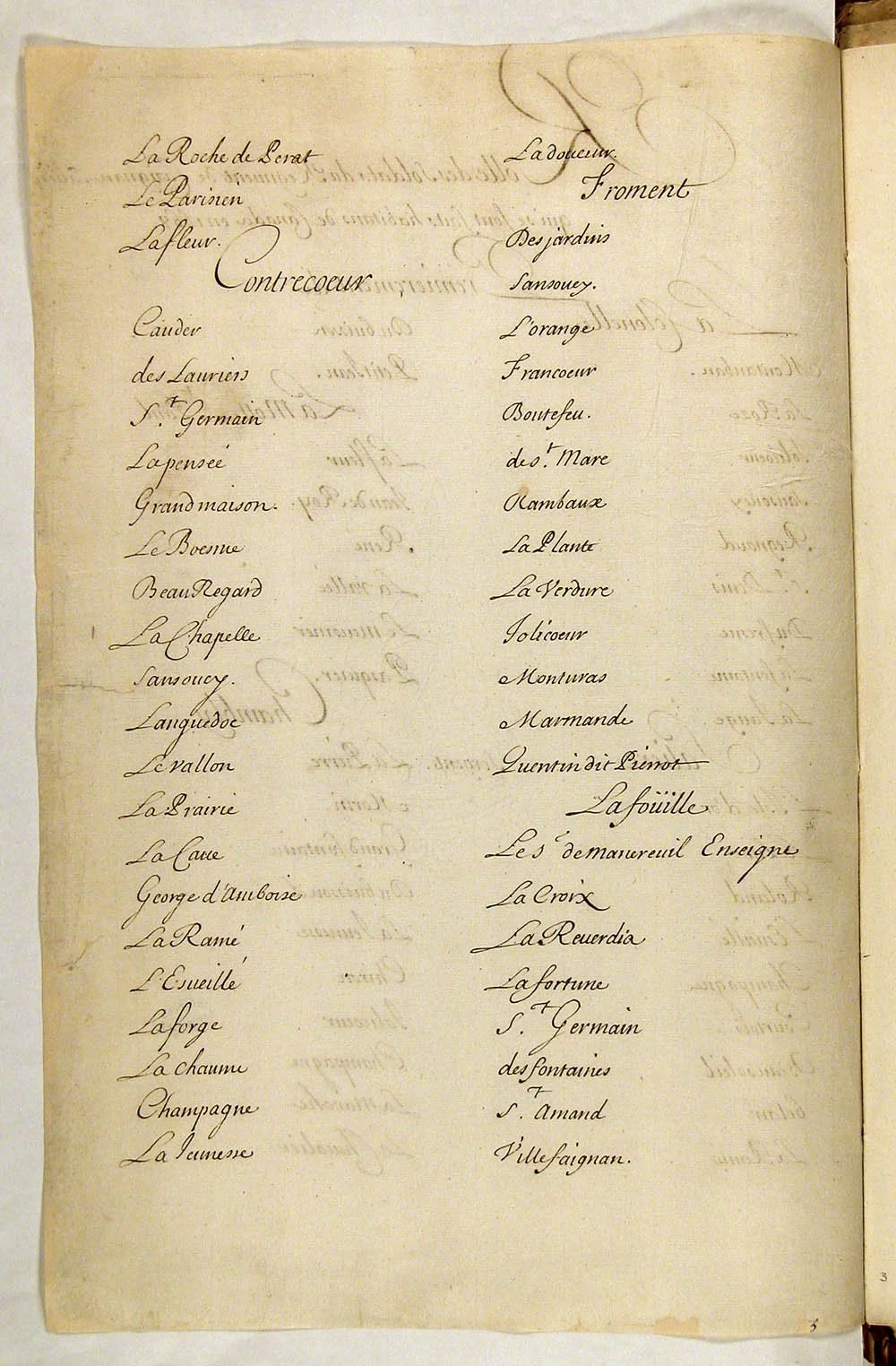

Jacques’s dit name appears on the “Rolle des Soldats du Regiment de Carignan Salière qui se sont faits habitans de Canada en 1668" (List of the Soldiers of the Carignan-Salières Regiment who became inhabitants of New France in 1668) (Library and Archives Canada)

On April 29, 1674, Jacques and fellow Longueuil resident Pierre Rebours established a company in order to trade goods with Indigenous nations. The agreement, penned by notary Bénigne Basset, confirms that Jacques was unable to sign his name.

On October 9, 1674, Jacques received a land concession in the seigneurie of La Prairie-de-la-Madeleine at Côte Saint-Lambert. Saint-Lambert is located just east of the Island of Montréal, across the St. Lawrence. Jacques’s associate, Pierre Rebours, received a similar plot of land on the same day. Two years later, on March 19, 1676, Rebours sold his land to Jacques.

Jeanne Denault

Jeanne Denault, daughter of Antoine Denault and Catherine Leduc, was born around 1647 in the parish of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois in Paris, France. [The spelling of Jeanne's surname varies greatly on documents: Denault, Denot, Denote, Denotte, etc.]

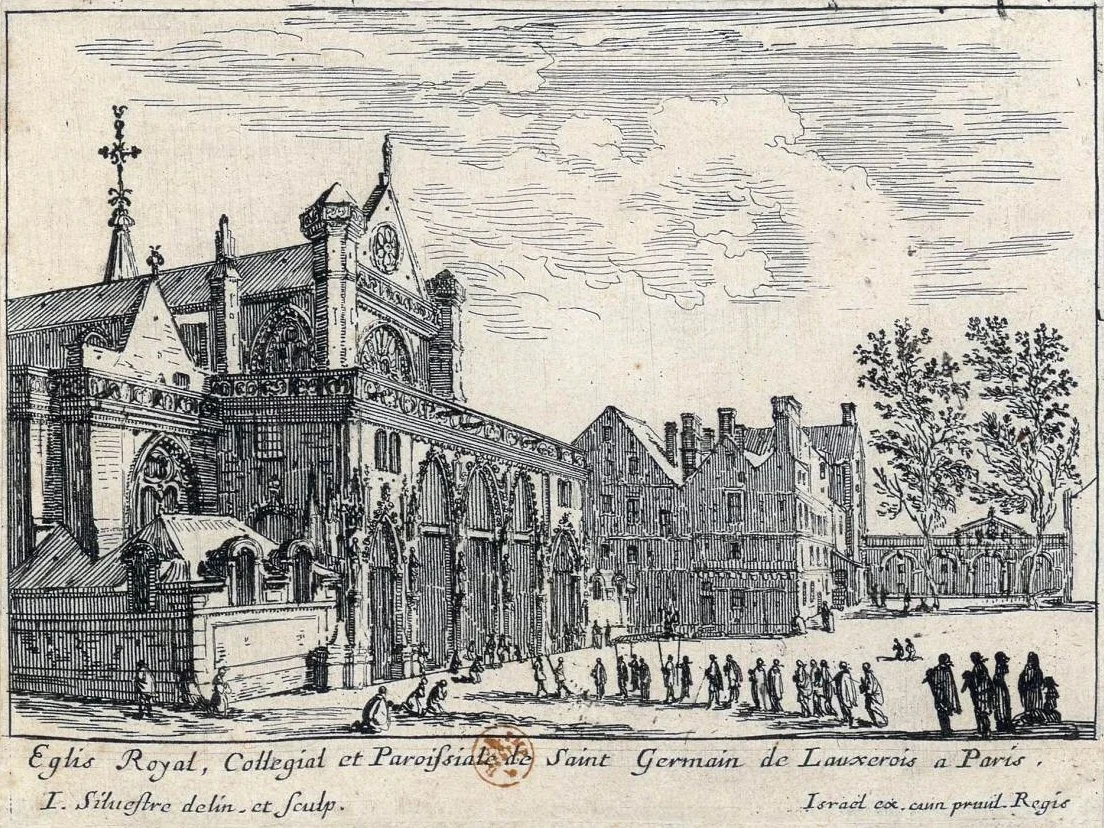

Located on the right bank in Paris’s first arrondissement, Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois is one of the city’s older parishes, with roots in the early medieval period, though the current church was constructed and expanded mainly between the 12th and 16th centuries. It stands opposite the Louvre and served as the Louvre’s parish church during the Ancien Régime. From 1608 to 1806 it functioned as the parish for residents of the Louvre palace complex, which explains the many ties to court artists and officials who were buried or commemorated there.

The church is also linked to the start of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre: its bell, “Marie,” is said to have tolled on the night of August 23–24, 1572, after which the killings of Huguenots spread across Paris and then the provinces. Regardless of the precise signal, contemporary Catholic and Protestant sources agree that the massacre began in the Louvre quarter and quickly engulfed the city. The church was damaged during the Revolution—closed and used for non-religious purposes—before being restored to worship in the early 19th century. The building is now listed as a protected Monument historique.

The church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, 17th-century engraving by Israël Silvestre (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Fille du roi

Jeanne lost her father when she was still a teenager. Perhaps faced with bleak prospects for her future, she was recruited to emigrate to New France as a “Fille du roi” in 1666. After her arrival in Québec City, Jeanne is believed to have lived with the Ursuline nuns for about a year.

The Filles du roi mural painted by Annie Hamel on a wall of the Saint-Gabriel school in Pointe-Saint-Charles, Montréal (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

Jeanne’s First Marriage

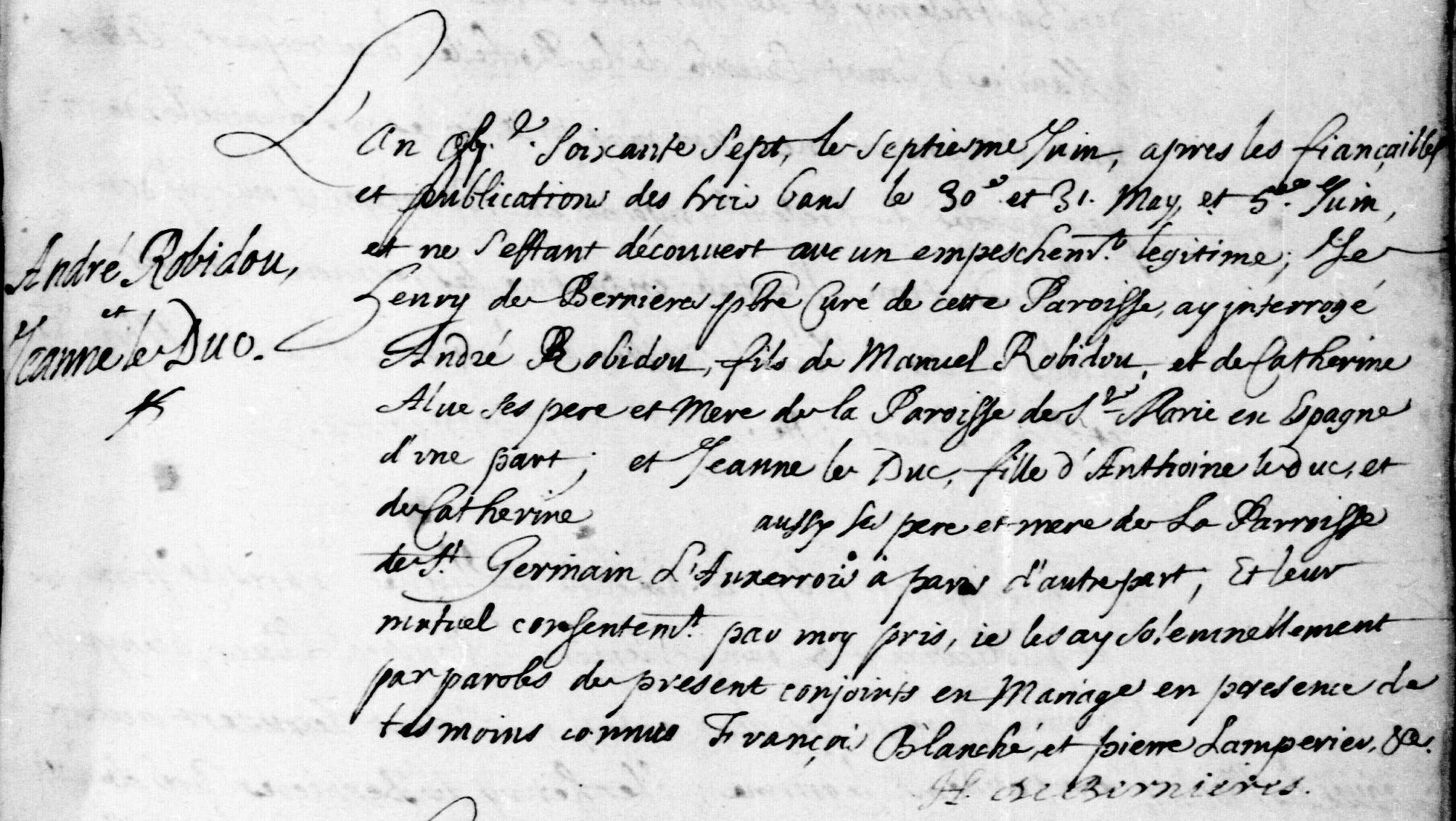

On the afternoon of May 16, 1667, notary Pierre Duquet de la Chesnaye drew up a marriage contract between Jeanne and André Robidou dit l’Espagnol in Québec. Robidou was a matelot (mariner) born in Spain, who likely arrived at Québec in the summer of 1661.

The contract mistakenly refers to Jeanne's surname as Leduc, her mother's name. Curiously, her parents are called [blank] Leduc and Catherine [blank]. André’s witnesses were [Élie?] Voisin, François Blanchet, and Joachim [Bourmicq?]. Jeanne’s witnesses were Noël Jérémie, sieur de la Montagne, Jeanne Pelletier (Jérémie’s wife), Catherine Houart, Guillaume Feniou, and Anne Gauthier (Feniou’s wife). The contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. Neither spouse was able to sign the document.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children. Inventories were drafted after death in order to list all the community's assets.

The couple married on June 7, 1667, in the parish church of Notre-Dame in Québec. Jeanne was about 20 years old; André about 27. Their witnesses were François Blanchet and Pierre Lamperier. Once again, the marriage record mistakenly refers to Jeanne's surname as Leduc. Her parents were listed as Antoine Leduc and Catherine [blank].

1667 marriage of Jeanne Denault and André Robidou dit l’Espagnol (Généalogie Québec)

The couple eventually settled in La Prairie. They had at least five children: Marie Romaine, Marguerite, Marie Jeanne, Guillaume, and Joseph.

André Robidou dit l'Espagnol died suddenly in the home of surgeon Fomblanche. He was buried in the parish cemetery of Notre-Dame on April 1, 1678, in Montréal. The burial record indicates that he was 35 years old and a resident of La Prairie.

Marriage of Jacques and Jeanne

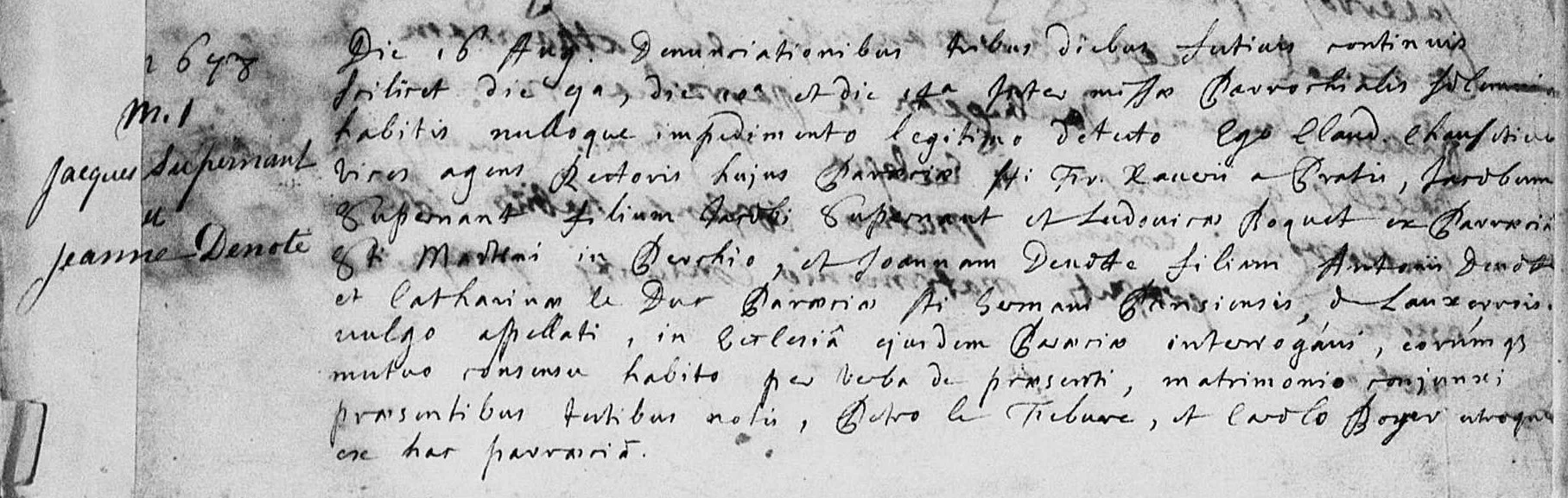

Finding herself a widow with four young children to care for, Jeanne remarried soon after the death of her husband. She and Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy married on August 16, 1678, in La Prairie. This time, Jeanne’s parents were listed as Antoine Denotte and Catherine Leduc. Their witnesses were Pierre Lefebvre and Charles Boyer, both residents of La Prairie.

1678 marriage of Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy and Jeanne Denault (Généalogie Québec)

Jacques and Jeanne settled in La Prairie, where they had at least eight children:

Jean (1679–1680)

Marie Marguerite (1681–1684)

Pierre (1683–1739)

Laurent (ca. 1685–1752)

Marie Catherine (1686–1762)

Claude (1688–1689)

Marie (ca. 1690–1717)

Anne (1692–1692)

In the years that followed his marriage, Jacques sold two plots of land located in Saint-Lambert:

February 6, 1679: sale to François Couturier

June 1, 1681: sale to Jean Bouthiller

Unfortunately, the details are not known, as the documents have not been digitized.

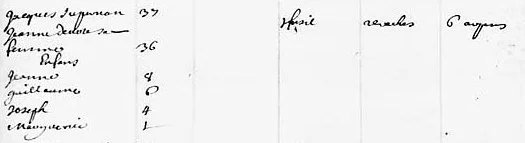

1681 census for the “Supernon” household (Library and Archives Canada)

In 1681, Jeanne and Jacques were recorded in the census of New France living in La Prairie with their children: Jeanne, Guillaume, Joseph (the three Robidou children) and Marguerite (Surprenant). They owned six arpents of “valuable” land (cleared and under cultivation), two cows and one gun.

In the 1680s and 1690s, Jacques and Jeanne were named in several notarial documents:

July 23, 1680: daughter Romaine Robidou, age 11, was hired as a domestic servant by alderman Pierre Nolan and his wife Catherine Houart, innkeepers in Québec. [Houart was a witness at Jeanne’s first marriage contract signing.] The couple promised to feed, house, care for, and educate Romaine in exchange for her service, as well as “treat her humanely.”

October 11, 1689: Jacques and Jeanne entered into an agreement with master butcher Jean Roy and his wife Françoise Saulnier. The couples agreed to cooperate on the upcoming harvest on their respective farms in Saint-Lambert, each supplying one working ox.

November 28, 1693: Jacques, a resident of Saint-Lambert, contracted out his son Jacques (7 or 8 years old) as a servant to merchant Nicolas Janvrin dit Dufresne in Montréal, admitting that he could not “raise him as he knows he should.” Laurent’s age was erroneously recorded as 10 in the contract, which stated that he would work for Dufresne until he was 25 years of age. Dufresne promised to feed, house, care for, and educate Laurent in exchange for his service, as well as treat him humanely. In a sense, this was akin to an adoption.

April 24, 1696: Jacques purchased a land concession in Saint-Lambert from Jacques Denault dit Detailly [no known relation to Jeanne] and Marie Rivet, his wife, for 250 livres. The land measured two arpents of frontage facing the St. Lawrence by 20 arpents deep. Jacques was described as a resident of Saint-Lambert.

June 11, 1696: an agreement was concluded between Jacques and Jeanne and the four surviving Robidou children and their spouses. Two arpents of land from the community of Jeanne and her first husband were divided equally between the four children. The house on the property was to be appraised, and the profits distributed equally among the four children, as were the farm animals still part of the community of goods.

March 3, 1697: Jacques, still a resident of Saint-Lambert, sold land in Saint-Lambert at a place called Mouillepied to Étienne Truteau for 135 livres. It measured one arpent of frontage facing the St. Lawrence by 20 arpents deep. This was part of the land previously sold to Jacques by Pierre Rebours.

Deaths of Jeanne and Jacques

Jeanne Denault died sometime between June 11, 1697 (marriage of son Guillaume), and June 16, 1697 (a notarial record in which her husband Jacques was described as a widower). Her burial record has not been located. She would have been about 50 years old.

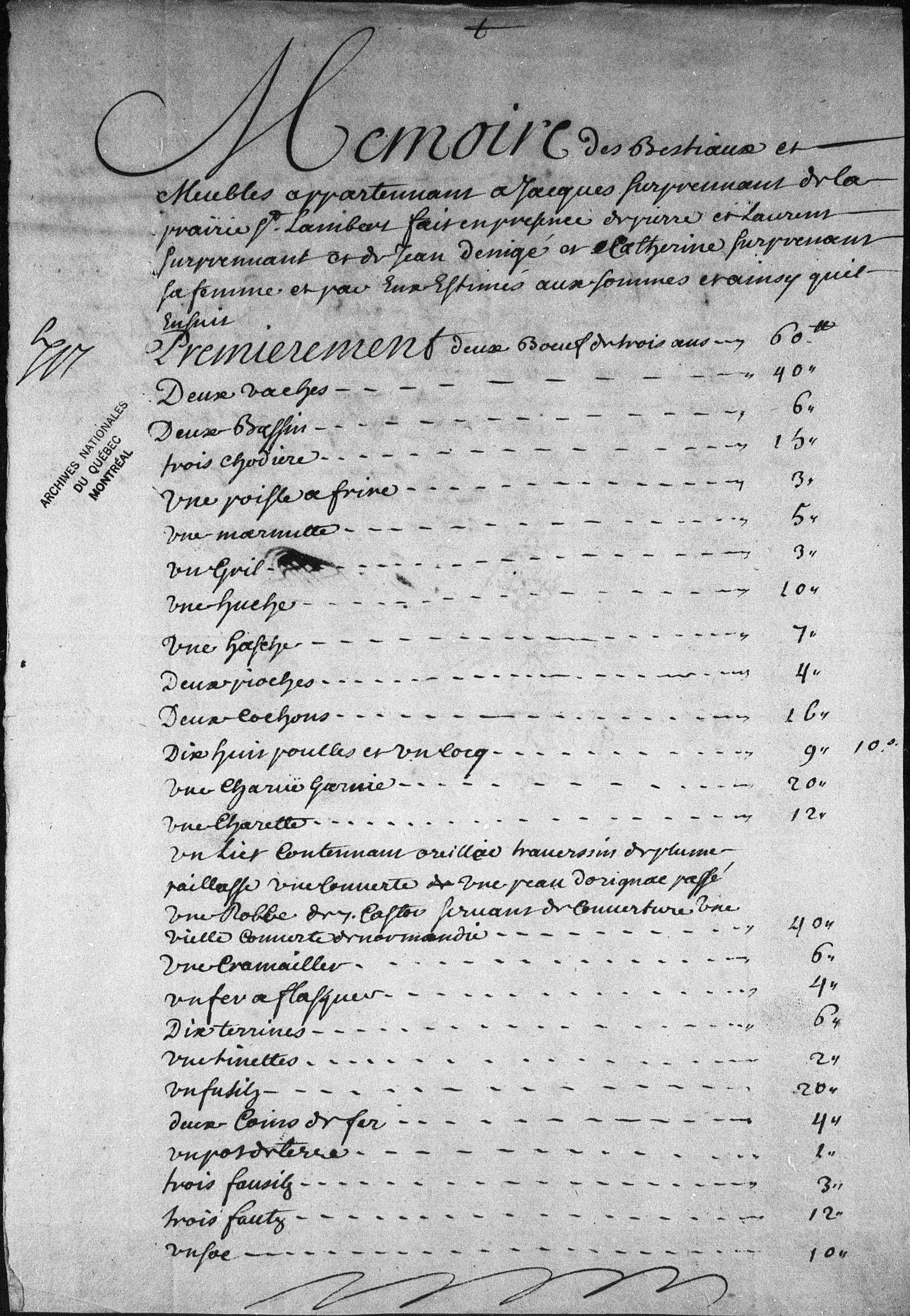

Jacques’s name appears for the last time in a notarial record on March 22, 1708. Perhaps in declining health, he donated his land to his son Laurent, with the agreement of his other children Pierre, Catherine, and Marie. The land, located in Saint-Lambert, measured two arpents of frontage by 20 arpents deep. The seigneurial rente was six deniers for each of the 40 arpents, plus two capons, which Laurent became responsible for going forward. Jacques also gave Laurent his furniture and farm animals, which were itemized in a mémoire attached to the donation document. In exchange, Laurent promised to feed, house and care for his father until his death, and to ensure his burial after he passed.

Extract of the mémoire enumerating Jacques’s possessions (FamilySearch)

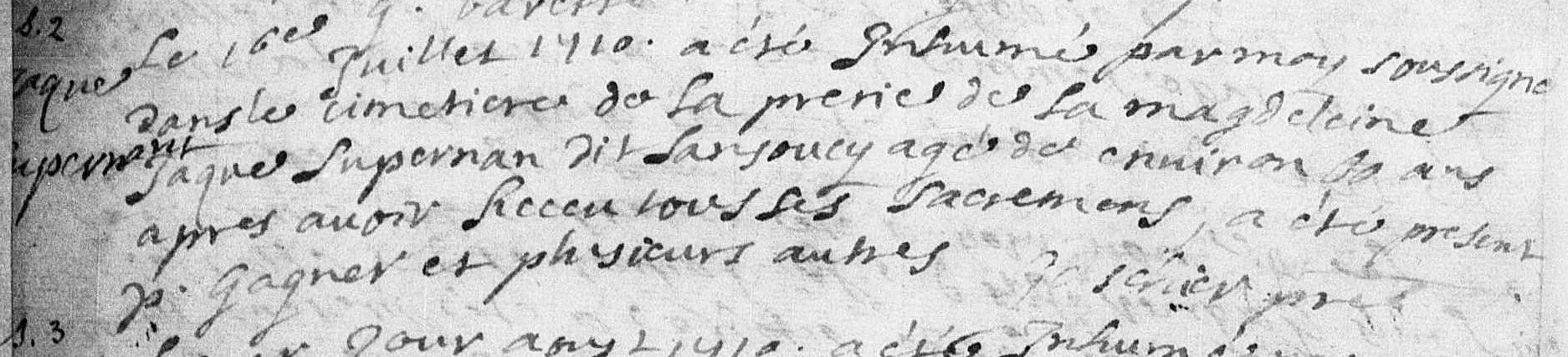

Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy died at about 66 years of age. He was buried on July 16, 1710, in the parish cemetery of La Prairie. [The date of death was omitted from the burial record, which also states that he was “about 60.”]

1710 burial of Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy (FamilySearch)

From French Roots to a North American Lineage

Jacques Surprenant dit Sansoucy's transformation from French soldier to Canadian settler exemplifies the founding generation of New France. Arriving in 1665 as a teenage recruit from tiny Saint-Martin-des-Pézerits, he participated in the Carignan-Salières Regiment's campaigns that secured peace with the Iroquois nations and established French control over the St. Lawrence Valley. His 1678 marriage to Jeanne Denault—herself a Fille du roi who had already established a family with her first husband—created a blended household that would produce eight more children.

Together they navigated the challenges of colonial life in Saint-Lambert, acquiring and managing land, raising children from both marriages, and participating in the complex network of notarial agreements that structured New France society. When Jacques died in 1710, he had spent forty-five years as a habitant, leaving behind descendants who would carry the Surprenant name through Québec and eventually into the United States, where it would evolve into Supernois and Supernaugh. His decision to remain in New France after military service—one shared by over 400 fellow soldiers—helped establish the demographic foundation that allowed French culture to persist in North America for centuries to come.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66720 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), marriage of Andre Robidou and Jeanne Leduc, 7 Jun 1667, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/49029 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), burial of Andre Lespagnol, 1 Apr 1678, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/18850 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), marriage of Jacques Supernant and Jeanne Denotte, 16 Aug 1678, La Prairie (La-Nativité-de-la-Ste-Vierge); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/19213 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), burial of Jacques Supernan Sansoucy, 16 Jul 1710, La Prairie (La-Nativité-de-la-Ste-Vierge); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

"Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NNY6?cat=koha%3A426906&i=1960&lang=en : accessed 15 Oct 2025), establishment of a company between Pierre Rebours and Jacques Supernan dit Sansoucy, 29 Apr 1674, images 1961-1962 of 3072; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1663-1687 // Pierre Duquet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-Y19H?cat=koha%3A1175224&i=564&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), marriage contract of André Robidou and Jeanne Leduc, 16 May 1667, images 565-567 of 2541; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1677-1696 // Claude Maugue," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-GS62-F?cat=koha%3A427707&i=1178&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), work contract between Romaine Robidou and Catherine Houar et Nollan, 23 Jul 1680, images 1179-1180 of 2531; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1677-1696 // Claude Maugue," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-93ZX-C?cat=koha%3A427707&i=2503&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), agreement between Jean Roy and Françoise Saulnier, and Jacques Surprenant and Jeanne Denot, 11 Oct 1689, images 2504-2505 of 3150; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1677-1696 // Claude Maugue," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-SJFQ?cat=koha%3A427707&i=1002&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), work contract between Laurent Surprenant and Nicolas Janvrain dit Dufresne, 28 Nov 1693, images 1003-1005 of 3080; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-MWJ6-7?cat=koha%3A541271&i=893&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), sale of land by Jacques Deneau dit Detaillis and Marie Rivé, to Jacques Surprennant, 24 Apr 1696, images 894-895 of 2856; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-MWNN-X?cat=koha%3A541271&i=1962&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), Agreement Between Jacques Surprenant, widower of Jeanne Devote, and Jean Patenoste and Romaine Robidou, and Gabriel Lemieux and Jeanne Robidou, 16 Jun 1697, images 1963-1972 of 2856; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-MWJR-1?cat=koha%3A541271&i=1618&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), sale of land by Jacques Surprennant dit Sansoucy to Etienne Trutau, 3 Mar 1697, images 1619-1620 of 2856; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-2BYS?cat=koha%3A541271&i=189&lang=en : accessed 16 Oct 2025), agreement and land donation between Jacques Surprennant to Laurent Surprenant, 22 Mar 1708, images 190-195 of 3055; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Fonds Ministère des Terres et Forêts - Archives nationales à Québec," document abstract, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/276927 : accessed 15 Oct 2025), "Concession dans la seigneurie de La Prairie-de-la-Madeleine (Laprairie) accordée à Jacques Surprenant à la Côte Saint-Lambert," 9 Oct 1674, reference E21,S64,SS5,SSS15,D1,P86, Id 276927.

"Fonds Ministère des Terres et Forêts - Archives nationales à Québec," document abstract, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/276937 : accessed 15 Oct 2025), "Concession dans la seigneurie de La Prairie-de-la-Madeleine (Laprairie) accordée à Pierre Rebours à la Côte Saint-Lambert," 9 Oct 1674, reference E21,S64,SS5,SSS15,D1,P87, Id 276937.

"Fonds Ministère des Terres et Forêts - Archives nationales à Québec," document abstract, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/277197 : accessed 15 Oct 2025), "Vente par Pierre Rebours à Jacques Surprenant à la Côte Saint-Lambert," 19 Mar 1676, reference E21,S64,SS5,SSS15,D1,P113, Id 277197.

"Fonds Ministère des Terres et Forêts - Archives nationales à Québec," document abstract, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/277547 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), "Vente par Jacques Surprenant à François Couturier à la Côte Saint-Lambert," 6 Feb 1679, reference E21,S64,SS5,SSS15,D1,P148, Id 277547.

"Fonds Ministère des Terres et Forêts - Archives nationales à Québec," document abstract, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/277717 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), "Vente par Jacques Surprenant à Jean Bouthiller (Terre Saint-Lambert)," 1 Jun 1681, reference E21,S64,SS5,SSS15,D1,P165, Id 277717.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau", Library and Archives Canada (https://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ : accessed 16 Oct 2025)), entry for Jacques Surprenant, 14 Nov 1681, La Prairie, Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/69204 : accessed 15 Oct 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques SURPRENANT SANSOUCY, person 69204.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/4744 : accessed 16 Oct 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques SURPRENANT SANSOUCY and Jeanne DENAULT, union 4744.

Jack Verney, The Good Regiment: The Carignan-Salières Regiment in Canada, 1665–1668 (Montréal : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991), 155 Appendix B.

Peter Gagné, Kings Daughters & Founding Mothers: the Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, Volume One (Orange Park, Florida : Quintin Publications, 2001), 204.

"L’église de Saint-Martin-des-Pezerits," Fondation du patrimoine https://www.fondation-patrimoine.org/les-projets/eglise-de-saint-martin-des-pezerits-projet-de-restauration/59358 : accessed 15 Oct 2025).

"Historique de l’église," Église Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois de Paris (https://saintgermainlauxerrois.fr/historique/ : accessed 16 Oct 2025).