François Prud’homme dit Failly & Marie Geneviève Daniel

Discover the story of François Prud’homme dit Failly and Marie Geneviève Daniel, a French-Canadian couple whose lives span from exile and settlement in 18th-century New France to the growth of their family in Québec. Learn about their journey from salt smuggling in France to farming in Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures, and their enduring legacy in French-Canadian genealogy.

François Prud’homme dit Failly & Marie Geneviève Daniel

From Salt Smuggler to Settler

François Prud’homme dit Failly, son of Louis Prud’homme and Marguerite Guédon (or Gaytanne), was born around 1717 in the parish of Saint-Julien in La Bazouge-des-Alleux, Maine, France. [The only two records that provide his mother’s name differ: Guaytanes [Gaytanne] on his marriage contract and Guesdon [Guédon] on his marriage record.]

Located approximately 250 kilometres southwest of Paris, the rural commune of La Bazouge-des-Alleux lies in the present-day department of Mayenne in the region of Pays de la Loire. Today, it has a population of 550 residents.

Location of La Bazouge-des-Alleux in France (Mapcarta)

The church of Saint-Julien in La Bazouge-des-Alleux (photo by GO69, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

The church of Saint-Julien, where François was likely baptized, dates to the Romanesque period, making it several centuries old by the time of his birth. Though altered over time, its origins lie in the Middle Ages, when it first served the small farming community of La Bazouge-des-Alleux. Later chapels and furnishings were added in the 16th and 17th centuries, but the church's medieval core remains the historic heart of the parish.

Life in 18th-century La Bazouge-des-Alleux revolved around subsistence farming. Families typically cultivated rye, oats, buckwheat, and small vegetable plots, kept a few animals, and relied on communal rights to woods and pastures. Harvests were uncertain, and peasants remained vulnerable to shortages and debt. Economic opportunities were limited: some men hired out as day labourers or seasonal workers, while others took up trades such as weaving or carpentry, but few could expect to rise beyond subsistence. The burden of royal taxes—including the hated gabelle—weighed heavily, leaving little room for advancement. In such a context, young men sought other means to supplement their income.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (September 2025)

The Crime That Changed Everything

In 1740, François was convicted of “faux saunage” (salt smuggling) and incarcerated at Mayenne Prison. His conviction as a faux-saunier places François in a broader story of men exiled from France to Canada under the Ancien Régime. The faux-sauniers were salt smugglers caught in the web of the gabelle—France’s deeply unpopular salt tax that varied dramatically from region to region, with Maine being in a high-tax salt zone. In the 18th century, poverty and rising costs pushed many to risk the lucrative contraband trade, buying cheap salt in low-tax zones and reselling it where it was heavily taxed. Caught offenders faced fines, prison, the galleys, or exile.

Beginning in the 1720s, Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, Comte de Maurepas, turned to these salt smugglers as a cheap source of forced colonists for New France. Between 1730 and 1749, more than 600 faux-sauniers were deported, nearly half of all French arrivals in Canada during those years. Once in the colony, they were typically bound to contracts as farm labourers or hired as soldiers, with many eventually settling, marrying, and raising families. Their story illustrates both the crushing weight of the gabelle in rural France and the surprising ways in which criminal punishment shaped Canada’s demographic history.

Originally a Carolingian palace, Mayenne Castle was remodelled several times during the Middle Ages. It lost its role as a feudal residence and became a garrison castle in the 14th century, before being converted into a prison in the 18th century. The castle was purchased by the town of Mayenne in 1936, declared an archaeological site of national interest, and extensively excavated before being turned into a museum.

The Château and prison of Mayenne, where François was incarcerated (1908 postcard, Geneanet)

In the spring of 1740, François was ordered to be taken to the port city of Rochefort, approximately 260 kilometres south of Mayenne. There, on June 10, he boarded the ship Le Rubis to begin his punishment—exile to Canada. After a transatlantic crossing of nearly two months, he arrived at Québec on August 7, 1740.

First Steps in Canada

Shortly after his arrival in Québec, François was hospitalized at the Hôtel-Dieu on July 17, 1740. The patient register states that he was 25 years old, from the province of Maine, and a “fauxssonier.” He was released from hospital ten days later. This is the first Canadian document that confirms François was a faux-saunier.

1740 Hôtel-Dieu patient register for François Prud’homme (Ancestry)

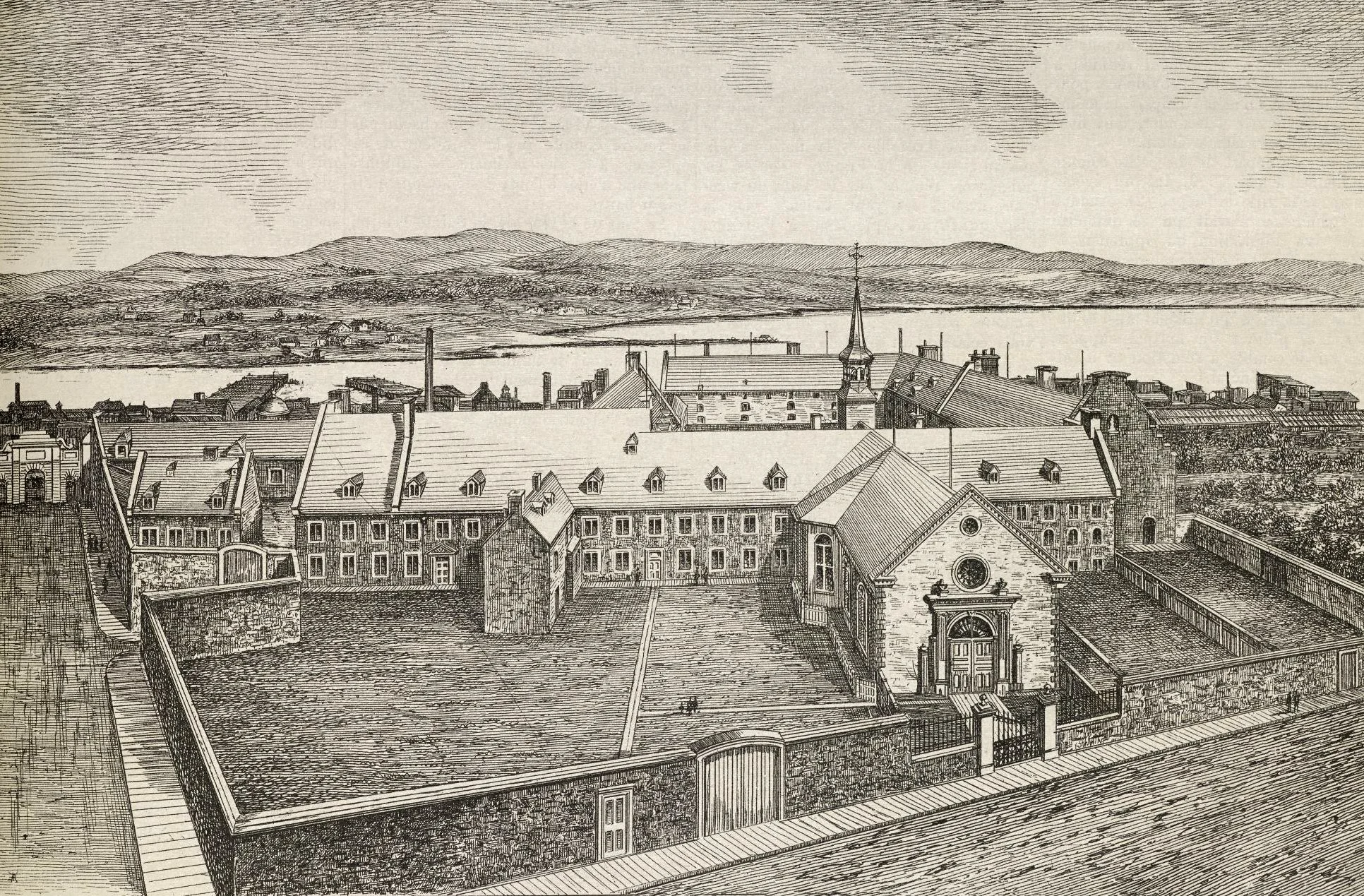

Drawing of the Hôtel-Dieu in Québec (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

François was hospitalized several more times at the Hôtel-Dieu over the years. The entries include the following information:

July 1, 1743: François Prud’homme, from Mayenne.

October 1, 1743: François Prud’homme, gardener of the hospital.

January 1, 1744: François Prud’homme, gardener of the hospital.

March 1, 1744: François Prud’homme, gardener of the hospital.

October 1, 1745: François Prud’homme, 30, from Mans, faux-saunier.

December 1, 1746 : François Prud’homme, gardener of the hospital.

As a hospital gardener, François would have tended the kitchen gardens or grounds of the convent-hospital, growing vegetables and medicinal herbs. This position was likely arranged by the religious order that effectively owned him as an indentured labourer upon arrival, as many exiled convicts were assigned to work for religious communities or merchants for a term. The position provided him with food, lodging, and a small wage – and perhaps gave him useful agricultural experience and contacts in the colony.

Land Acquisition

On March 28, 1745, François purchased land located in the “fourth range of the fief, land and seigneurie of Saint-Augustin” from François Robineau et Marie-Anne Huot for 360 livres. The plot and habitation measured two arpents “or thereabouts” of frontage by 30 arpents deep and was located between the lands of Charles Goulet and Laurent Amyot [Amiot] dit Villeneuve. The sale included “a log cabin approximately twenty-six feet long by twenty feet wide, with a shed made of stakes.”

The seigneurs of the land were the Hospitalières de l’Hôtel-Dieu (nuns), for whom François was working at the time. He agreed to pay the nuns one sol per arpent in area and one live capon (or 15 sols, at the discretion of the sisters) in seigneurial rentes, plus two sols and six deniers in cens, due annually on the feast day of Saint Martin.

Marie Geneviève Daniel, daughter of Thomas Daniel and Suzanne Lefebvre dite Boulanger, was born on May 26, 1722. She was baptized the same day in the parish of Saint-Jean on Île-d’Orléans. Her godmother was Marguerite Laverdière; no godfather was named.

1722 Baptism of Marie Geneviève Daniel (Généalogie Québec)

Geneviève grew up on Île-d’Orléans, alongside several full siblings and step-siblings, as both her parents had previous marriages. Her father was a sailor from Brittany, France.

Marriage and Children

On the afternoon of March 19, 1747, notary Claude Louet drafted a marriage contract between François Prud’homme and Marie Geneviève Daniel, at the home of Jean Coutant in Québec. François was recorded as a 30-year-old from “Bazouche” [Bazouge], “without a profession,” while Geneviève was a 26-year-old resident of the parish of Saint-Jean on Île-d’Orléans. His witnesses were his friends Jean Coutant, Jean [Hemond?], and Bonnet Giraudé [Giradet] (also a faux-saunier). Her witnesses were her uncle Charles Lefebvre, as well as her friends François Leclair and Philippe Noël. The contract followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. The prefix dower was set at 600 livres, and the preciput at 600 livres.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children. Inventories were drawn up after death in order to list all the community's assets.

The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him. The preciput was a benefit conferred by the marriage contract, usually on the surviving spouse, granting them the right to claim a specified sum of money or property from the community before the rest was divided.

François and Geneviève married on April 10, 1747, in the parish church of Saint-Pierre on Île-d’Orléans. He was recorded as a resident of Québec, while she lived in the parish of Saint-Jean on Île-d’Orléans. Their witnesses were François Roger [also a faux-saunier], Joseph Tessier, Jean Coutant, and François Daniel. The bride and groom declared they did not know how to sign.

The Church of Saint-Pierre on Île-d’Orléans

The church of Saint-Pierre on Île-d’Orléans—where François and Geneviève married in 1747— is the same stone parish church built between 1717 and 1719 on the site of an earlier wooden chapel from 1673. The parish itself was organised in 1678 and opened its registers in 1679. By the time of their wedding, generations of island families had already worshipped there. Its interior was repaired after damage during the 1759 Conquest and reworked in the early 1800s by artisans associated with the Baillairgé workshop. The historic church was deconsecrated in 1955 when a new church was built beside it; the old building was then acquired by the Québec government and classified in 1958 as a protected heritage site, one of the rare parish churches from the French Regime to survive on the island.

The parish church of Saint-Pierre on Île-d’Orléans (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

François and Geneviève settled on his land in Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures, where they had at least ten children:

François (1748–1792)

Marie Geneviève (1749–1814)

Joseph (1751–aft. 1762)

Françoise (1753–1783)

Marie Josèphe (1755–1834)

Marie Anne (1756–1833)

Marie Thérèse (1759–1824)

Jean Baptiste (ca. 1761–1789)

Augustin (1763–1837)

Louis (1767–1817)

By the mid-1740s, after marrying Geneviève, François transitioned to being a full-time habitant farmer on his land in Saint-Augustin. The daily life of a habitant was labor-intensive: François would have spent long days clearing forest, plowing his fields, sowing and harvesting crops (likely wheat, oats, peas, and hay for the animals), and maintaining their home and outbuildings.

Land Transactions

On March 24, 1750, François and Geneviève sold a plot of land located in the parish of Saint-Jean on Île-d’Orléans to Louis Cochon dit Laverdière for 400 livres. François and Geneviève were recorded as residents of côte des Mines, in the seigneurie and parish of Saint-Augustin. The land measured approximately three-quarters of an arpent of frontage facing the St. Lawrence, by a depth reaching the line that crosses the island from point to point. It bordered the lands of François Daniel (Geneviève’s brother) on one side and the buyer’s land on the other. Geneviève had received this land as part of her inheritance following her parents’ deaths, her father having died five days prior to the transaction.

On May 9, 1753, François and André Arnoux dit Villeneuve leased farmland in the seigneurie of Saint-Augustin from Marie Antoinette Denis, the widow of Laurent Amiot and François’s neighbour. François and André leased the land for one year at the cost of 50 livres. The land measured two and a half arpents of frontage by 30 arpents deep. The men promised to maintain the fences that were erected on the land, as well as the roads that crossed it.

In 1762, a census was conducted for the Government [district] of Québec, taken shortly after the British conquest. François was listed with two and a half arpents of land cleared and cultivated, though he indicated that he had planted no minots of seed that year. He owned one ox, two cows, two young bulls, one sheep, one horse and no pigs. This modest profile – a small area of cleared land and a few head of cattle – confirms that François was a typical habitant with a small subsistence farm.

Death of François

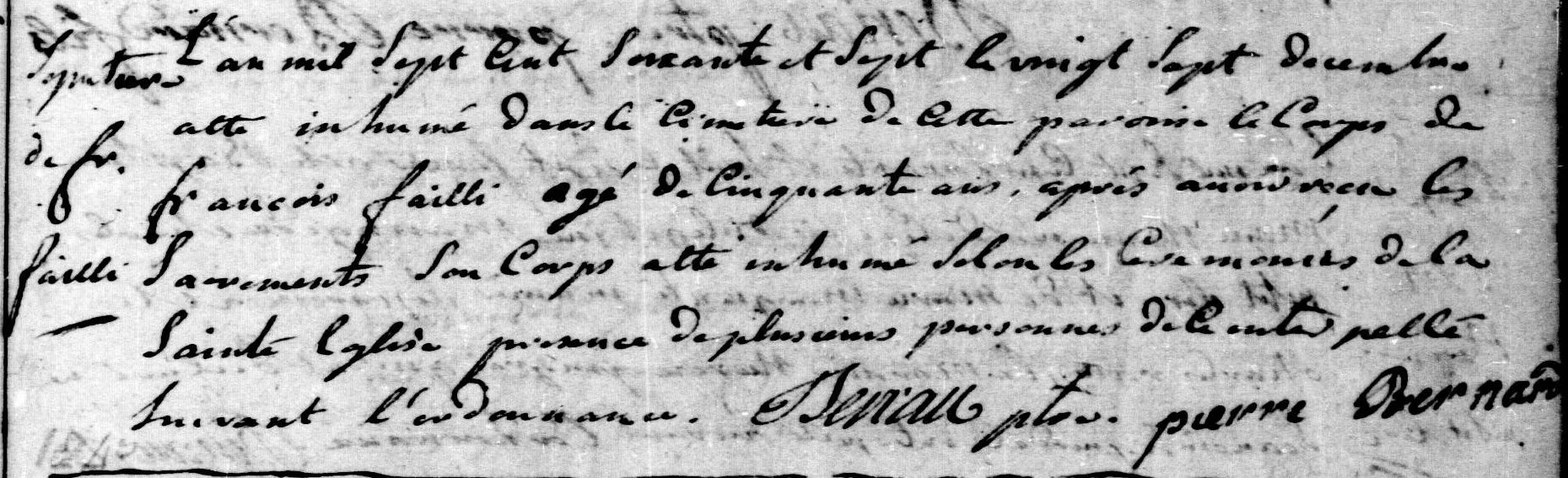

François Prud’homme dit Failly died at approximately 50 years of age “after having received the sacraments.” He was buried on December 27, 1767, in the parish cemetery of Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures, “in the presence of many people.” [The burial record does not include the date of death.]

1767 burial of François Prud’homme dit Failly (Généalogie Québec)

As was customary after the death of a parent, an assembly of friends and family members was held to elect a guardian and substitute guardian for the nine minor children of François and Geneviève in July 1769. Since her husband’s death, Geneviève had been living in dire conditions and had additional motivation to have the guardians elected. A translated portion reads:

“Humbly begs Marie Geneviève Daniel, widow of François Prudom of Faÿ, habitant of the seigneurie and parish of Saint-Augustin, stating that due to the death of the said deceased her husband, she finds herself liable for the sum of two hundred and six livres and two sols owed to several individuals on her community [with her husband], which sum she is unable to pay, being unable even to support her family, which consists of eight [sic] minor children, unless she is authorized to consent to the sale of part of the land belonging to her community [...]."

Marie Geneviève was elected the guardian of her minor children, and Charles Bussières the substitute guardian. She was given permission to sell the land.

Guardianship

Under the Coutume de Paris (the law in force in Canada), a tuteur (guardian) had to be appointed whenever a minor stood to receive property. Because the Custom required equal partition among children, a tutelle (guardianship) was opened at a parent’s death to manage a minor’s share until majority or emancipation by marriage or court order. With early parental deaths common, guardianships were routine.

Appointment generally favoured the surviving spouse as guardian, chosen with the advice of a family council—often seven close relatives and family friends convened under a judge’s supervision. The judge intervened mainly in cases of dispute or refusal to serve. The Custom also provided for a subrogé tuteur (substitute guardian) selected from family or close friends to safeguard the minors’ interests and verify the inventory of community property.

Inventory

On July 22, 1769, notary André Genest drew up an inventory of Marie Geneviève’s goods from her community with her deceased husband. Though not all items are legible, the inventory contained the following:

In the kitchen: a pot hook (for the chimney rack); a cooking pot; a small iron cauldron; a frying pan; an earthenware dish; three plates; a small terrine; a coffee pot with two cups; seven old iron forks; eleven pewter spoons; a pewter plate; a tumbler; a drinking cup; an iron-hooped barrel; a medium tub; a small basin; three jugs (one stoneware) and a small stoneware jug; two axes; a hammer and a trowel; a pickaxe; a sandstone grindstone; sixteen bottles; a billhook and a small saw; three spinning wheels; a chest and a sideboard, “very old”; two horse harnesses and two old collars; wool-carding combs.

In the bedroom: a lamp, a chest, an old axe, one of the deceased's garments, an old armchair.

In the yard: some old carts; a plough complete with its fittings; an old sleigh.

Animals: a seven-year-old horse, chestnut (red-coated); a four-year-old cow; three ewes and a lamb.

The inventory also included debts totalling over 180 livres, as well as the couple’s lands, including the home property in Saint-Augustin and the buildings on it: an old wooden house measuring twenty-five feet long by twenty feet wide, comprising a bedroom and kitchen, covered with planks as well as doors, and a stone fireplace. A barn or shed and stable in a state of disrepair. Also listed in the inventory were important documents belonging to Marie Geneviève.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (September 2025)

A few days later, on July 28, 1769, Marie Geneviève was finally able to sell a portion of her land in the seigneurie of Saint-Augustin to settle her debts. She sold a portion measuring one and a half arpents by thirty arpents deep to Ignace Cliche for 400 livres.

Marie Geneviève’s Final Years

On March 23, 1781, 58-year-old Marie Geneviève donated all her movable and immovable property, as well as her animals, to her 20-year-old son Jean Baptiste. In turn, he agreed to pay the land’s rentes and cens going forward. He also promised to provide lodging, heating, lighting, food, and care for his mother in both health and sickness, and to have her buried and masses said for the repose of her soul after her death.

This kind of arrangement, known as a subsistence contract or donation rentière, was common and underscores that in widowhood Geneviève’s well-being depended on living with her adult children. In practical terms, after 1781 her daily tasks would have lessened as her son took over the heavy work, although she likely still contributed by doing lighter chores as long as she was able.

Death of Marie Geneviève

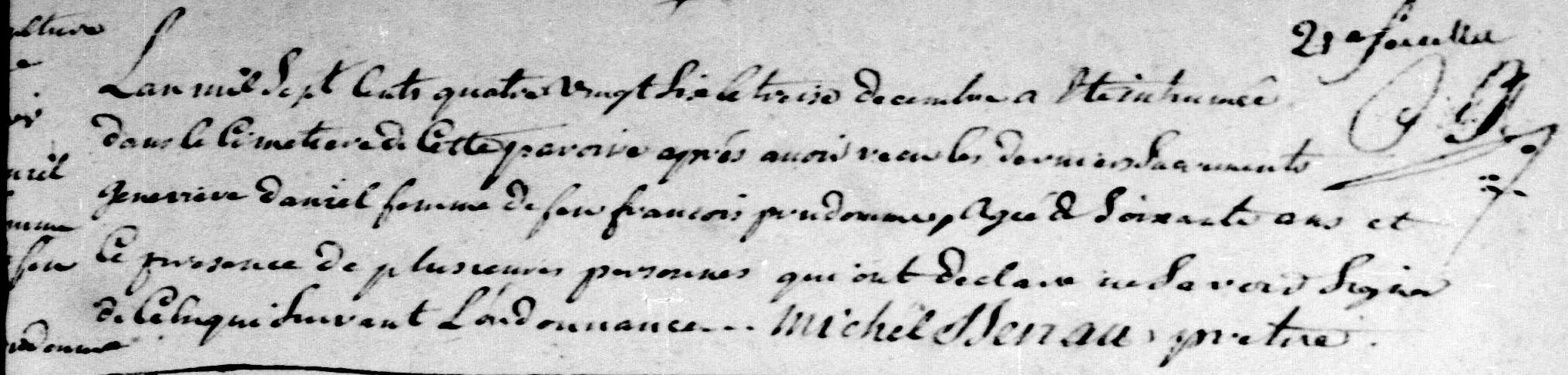

Marie Geneviève Daniel died at age 64. She was buried on December 13, 1786, in the parish cemetery of Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures, “in the presence of many people.” [The burial record does not include the date of death and erroneously states she was 60.]

1786 burial of Marie Geneviève Daniel (Généalogie Québec)

A Legacy of Resilience

François Prud'homme dit Failly and Marie Geneviève Daniel represent the human story behind New France's colonial experiment. François arrived in 1740 as a convicted salt smuggler, yet within seven years had acquired land, married, and begun the transformation from criminal exile to respected habitant. His marriage to Geneviève, daughter of an established Island family, marked his full integration into colonial society. Together they raised ten children on their farm in Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures, navigating the economic challenges of subsistence agriculture while fulfilling their obligations to the seigneurial system. After François's death in 1767, Geneviève's struggle to maintain the family property and provide for her minor children illustrates both the vulnerabilities of widowhood in colonial society and the legal protections offered by the Coutume de Paris. Their story demonstrates how New France's colonial policies could transform unwilling immigrants into founding families, and how ordinary people built enduring communities through marriage, land ownership, and mutual obligation.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"L’église St-Julien," La Bazouge-des-Alleux (https://labazougedesalleux.fr/l-eglise-st-julien : accessed 24 Sep 2025).

Henri Sée, “Economic and Social Conditions in France During the Eighteenth Century,” 1927, digitized by McMaster University (https://historyofeconomicthought.mcmaster.ca/see/18thCentury.pdf : accessed 24 Sep 2025).

Marcel Fournier, Faux-sauniers et contrebandiers de France déportés au Canada : 1730-1743 (Québec, Les Éditions GID, 2023), 254.

Kim Kujawski, "Off to Canada for the rest of your life! The story of the ‘faux-sauniers’ exiled to New France,” The French-Canadian Genealogist (https://www.tfcg.ca/faux-sauniers-in-canada : accessed 25 Sep 2025).

“Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968,” digital images, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_31480857?usePUB=true&_phsrc=jbw42634&pId=1655033898 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), Hôtel-Dieu Registry (1740-1751), entry for François Prud’homme, 17 Jul 1740; citing original data: Drouin Collection, Institut Généalogique Drouin.

Marcel Fournier and Gisèle Monarque, Registre journalier des malades de l'Hôtel-Dieu de Québec (Montréal : Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo, 2005), entries for François Prud’homme.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/38682 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), baptism of Genevieve Daniel, 26 May 1722, St-Jean (Île d'Orléans).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/142992 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), marriage of Francois Prudome and Marie Genevieve Daniel, 10 Apr 1747, St-Pierre (Île d'Orléans).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/375033 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), burial of Francois Failli, 27 Dec 1767, St-Augustin-de-Desmaures (St-Augustin).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/391603 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), burial of Genevieve Daniel, 13 Dec 1786, St-Augustin-de-Desmaures (St-Augustin).

"Actes de notaire, 1736-1756 // Gilbert Boucault de Godefus," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LM-Z9F5-3?cat=koha%3A647493&i=459&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), sale of land by François Robineau and Marie-Anne Huot to François Prudhomme, 28 Mar 1745 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1739-1767 // Claude Louet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L8-G2Z2?cat=koha%3A730529&i=1187&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), marriage contract of François Prud’homme and Marie Genevieve Daniel, 19 Mar 1747 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1734-1759 // Christophe-Hilarion Dulaurent," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L8-G2Z2?cat=koha%3A730529&i=1187&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), sale of land by François Prud'homme and Geneviève Daniel to Louis Cochon dit Laverdiere, 24 Mar 1750 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1748-1756 // Prisque Marois," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L8-PR8S?cat=koha%3A729893&i=2778&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), farm lease by Marie-Antoinette Denis to André Arnoux dit Vilneuve and François Prudhomme, 9 May 1753 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1738-1783 // André Genest," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYX-4SZM-4?cat=koha%3A775848&i=873&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), inventory of the property of Geneviève Daniel, widow of François Prudom, 22 Jul 1769 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1738-1783 // André Genest," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYX-4S8T-J?cat=koha%3A775848&i=896&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), sale of land by Marie-Geneviève Daniel to Ignace Cliche, 28 Jul 1769 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1738-1783 // André Genest," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3NX-CQ18?cat=koha%3A775848&i=265&lang=en : accessed 24 Sep 2025), transfer of movable and immovable property by Marie-Geneviève Daniel to Jean-Baptiste Prudom, 23 Mar 1781 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Fonds Cour supérieure. District judiciaire de Québec. Tutelles et curatelles - Archives nationales à Québec," Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/71420 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), "Succession et tutelle aux mineurs de feu François Prudom dit Fay (Prudhomme dit Failly), habitant de la seigneurie et paroisse de Saint-Augustin, et de Geneviève Daniel," 10 Jul 1769-27 Jul 1769, reference CC301,S1,D4331, Id 71420.

"Rapport de l’archiviste de la province de Québec pour 1925-1926," digital images, Archive.org (https://ia801302.us.archive.org/17/items/rapport03queb_0/rapport03queb_0.pdf : accessed 24 Sep 2025), transcription of the census of the government of Quebec in 1762, page 99.

"Historique : Saint-Pierre," Patrimoine religieux de l’île d’Orléans (https://www.patrimoinereligieuxio.leem.ulaval.ca/municipalite/saint-pierre : accessed 24 Sep 2025).

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/25479 : accessed 24 Sep 2025), dictionary entry for Francois PRUDHOMME FAILLY and Marie Genevieve DANIEL, union 25479.

Jean-Philippe Garneau, "La tutelle des enfants mineurs au Bas-Canada : autorité domestique, traditions juridiques et masculinités," Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, volume 74, number 4, spring 2021, p. 11–35, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/1081966ar).