François Bigras & Marie Brunet

Discover the remarkable story of François Bigras (1665-1731) and Marie Brunet (1677-1756), French pioneers who left La Rochelle for New France. Follow their journey from voyageur contracts to land settlements in Lachine, and learn how three generations of the Bigras family shaped the Great Lakes fur trade through Detroit and Michilimackinac.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

François Bigras & Marie Brunet

From La Rochelle to the Fur Trade of New France

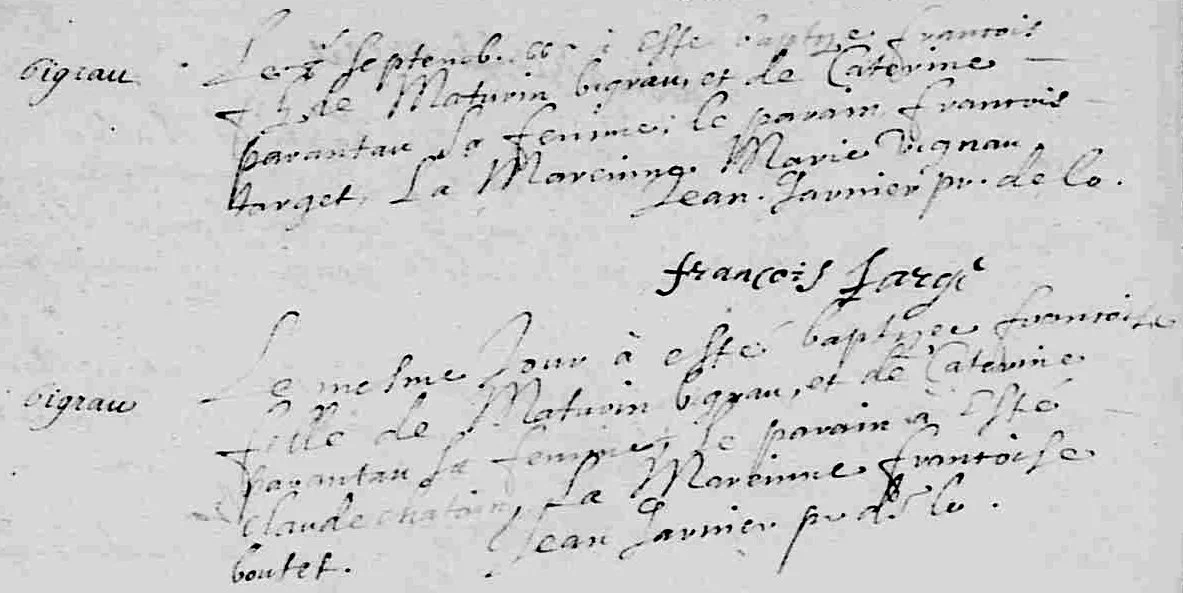

François Bigras, son of Mathurin Bigras (or Bigreau), a portefaix (porter), and Catherine Parenteau, was baptized with his twin sister Françoise on September 8, 1665, in the parish of Saint-Nicolas in La Rochelle. His godparents were François Target and Marie Vignau.

1665 baptism of François and Françoise Bigras (Archives départementales de la Charente-Maritime)

François and Françoise’s known siblings were Catherine (1661–1661), Catherine (born 1662), Marguerite (born 1663), Pierre (1667–1671), Mathurin (1669–1676), Marie (born 1671), and Anne (born 1673). All the Bigras children were baptized in the parish of Saint-Nicolas.

Family Origins

François’s mother, Catherine Parenteau, was baptized on December 18, 1633, in the parish of Sainte-Marguerite in La Rochelle. She married Mathurin Bigras on September 19, 1660, in the parish of Saint-Nicolas in La Rochelle.

Mathurin’s parents were François Bigras, a saunier (salt worker or merchant) and laboureur (ploughman), and Jacquette Cholet. Catherine’s parents were Antoine Parenteau, a farinier (miller), scieur de long (long sawyer), and charpentier (carpenter), and Anne Brisson. They married on January 23, 1633, in La Rochelle. Catherine’s grandparents were Antoine Parenteau and Jeanne Pérodin, and Jacques Brisson and Jacquette Peau.

Mathurin Bigras died at age 45 on March 3, 1679, and was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Nicolas. François was only 13 years old when he lost his father.

The Church of Saint-Nicolas

Église Saint-Nicolas was founded in 1145 as a small chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas on a small island. Over time, it became a parish church. During the Wars of Religion in the 16th century, La Rochelle, a major Protestant stronghold, saw many Catholic churches, including Saint-Nicolas, damaged or destroyed. The church suffered significant destruction during this period, as did many other religious sites in the city. After the French Revolution, the church fell into disuse and was repurposed for other functions. By 1887, a new parish church was built elsewhere in the city, and the original Église Saint-Nicolas was converted into a customs warehouse. It was later used for commercial purposes and, in 1978, became a hotel.

The Church of Saint-Nicolas, 1830 (Wikimedia Commons)

The former church of Saint-Nicolas, 1914 (Geneanet)

The Allure of New France

François had two aunts named Marie Parenteau, both born in the 1640s, who left La Rochelle for New France. The elder, born around 1641, likely arrived at the port of Québec in 1657 as a fille à marier. She married Robert Gagnon, and their family eventually settled on Île-d’Orléans. By 1662, both sisters had lost their parents. The younger Marie, born circa 1643, followed her older sister to New France, likely in 1671, as a fille du roi. Soon after, she married Antoine Pierre Fauvel, a tonnelier (cooper) and marchand (merchant), and settled in Québec City.

As a young man in La Rochelle, François would have been aware of his aunts’ migration to the colony. Their accounts of opportunity, combined with promises of free land for settlers, likely stirred his sense of adventure. He was able to read and write, suggesting he had received some formal education, a useful skill in the colony. The constant sight of ships departing La Rochelle for New France may have deepened his resolve. With both aunts established across the Atlantic, their example offered a powerful incentive.

By 1682, François had made the journey himself. He first appeared in the records of New France that year, living with his aunt Marie and her husband in Québec City. His connection to Antoine Pierre Fauvel led François at times to use the dit name Fauvel, later adopted by some of his children and still found in Québec today.

The Harbour of La Rochelle (1851 oil painting by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Wikimedia Commons)

Work Contracts and a First Land Concession

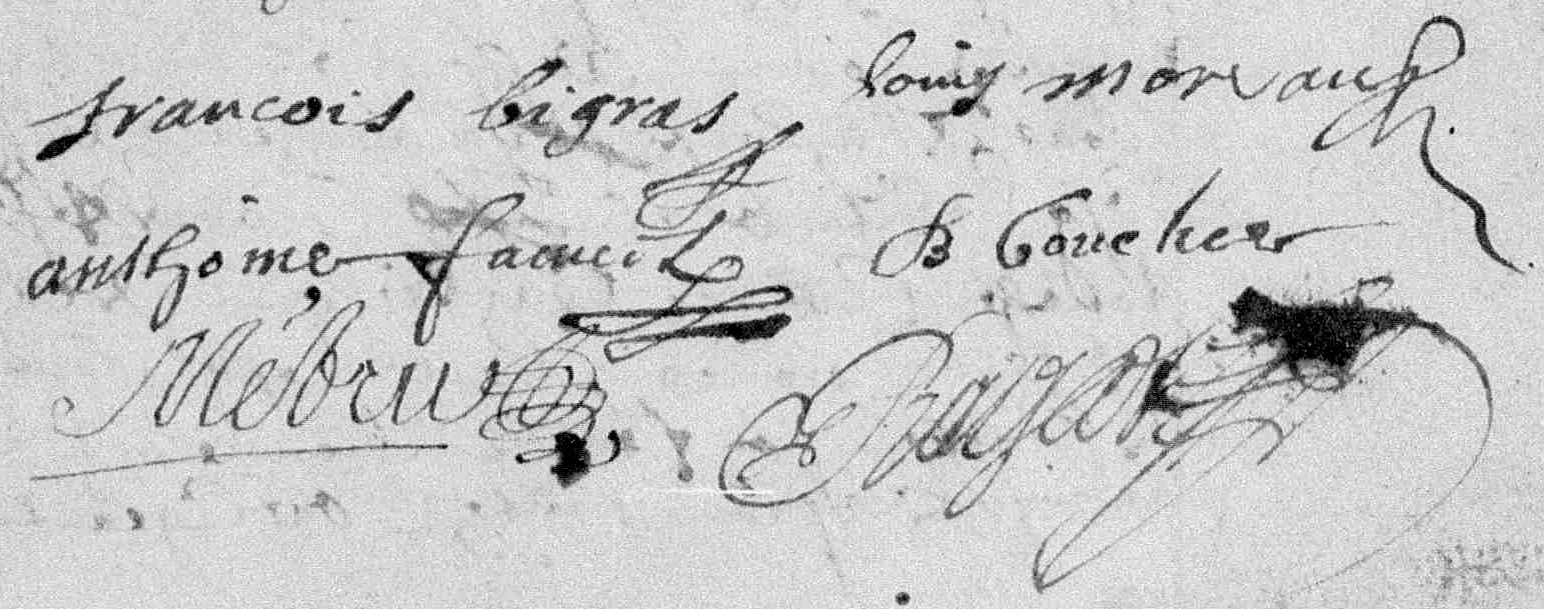

On July 14, 1682, at age 16, François signed a three-year contract with Louis Moreau, a surgeon of Château-Richer, to perform “whatever will be ordered of him.” His uncle, Antoine Pierre Fauvel, was present and gave consent. Moreau agreed to pay François 40 livres for the first year and 50 livres for each of the next two, in addition to room, board, and care. The contract, drawn up in Québec, also stipulated that François would be treated humanely. François, his uncle, and his new employer all signed the agreement.

Signature portion of the 1682 contract (FamilySearch)

The arrangement ended prematurely when Moreau died suddenly at home on January 12, 1683.

On October 2, 1684, François, then 19, received his first land concession in the seigneurie of Lachesnaye from Pierre Duquet de la Chesnaye. François was described as a resident of Île-d’Orléans, possibly living with his other aunt Marie. The concession measured six arpents of frontage on the St. Lawrence River by forty arpents deep. François was granted hunting and fishing rights and, in return, promised to clear and work the land, keep the roads on his property in good condition, and grind his grain at the seigneurial mill. The annual rente was set at six livres per arpent of frontage, six capons (or twenty sols each), and twenty sols in cens for the concession as a whole.

Barely a month later, on November 6, 1684, François entered into a second three-year contract, this time with notary Séverin Ameau and his wife Madeleine Beaudoin in Trois-Rivières. The terms, recorded by Pierre Duquet de la Chesnaye, promised François 60 livres the first year, 80 livres the second, and 110 livres the third, along with lodging, board, and humane treatment. His literacy suggests he may have worked as a secretary.

This contract seemingly conflicted with the obligations of his land grant, which required him to remain and improve the property. Such contradictions were not unusual, however. Land concessions were often granted with the expectation of eventual settlement, while in practice young men sometimes left to pursue waged employment, relying on informal arrangements, postponement of obligations, or the tolerance of the seigneur.

An Unusual Marriage Contract

In the summer of 1685, 19-year-old François was in Montréal, possibly on business for his employer. There he met Mathieu Brunet dit Létang, who offered him the hand of his daughter Marie. The complication was Marie’s age—only seven years old, far below the legal minimum of 12. One of ten children, she had been born on October 25, 1677, and baptized the following day at Cap-de-la-Madeleine.

Mathieu Brunet dit Létang and Marie Blanchard

Marie Brunet’s mother, Marie Blanchard, was a Fille du roi who arrived at Québec on September 25, 1667, and married six weeks later. Her French-born husband, Mathieu Brunet dit Létang, appears early and often in the courts—disputes over a seized rifle, an unauthorized canoe, and payment of a minot of wheat, illustrating the rough edges of settler life. In the 1680s he pushed west as a voyageur with Nicolas Perrot to Baie des Puants and the Mississippi, helping establish Fort-Saint-Antoine near Lake Pepin. This explorer’s path foreshadowed that of their future son-in-law, François Bigras and of several Bigras-Brunet grandsons who carried the trade deep into the Pays d’en haut.

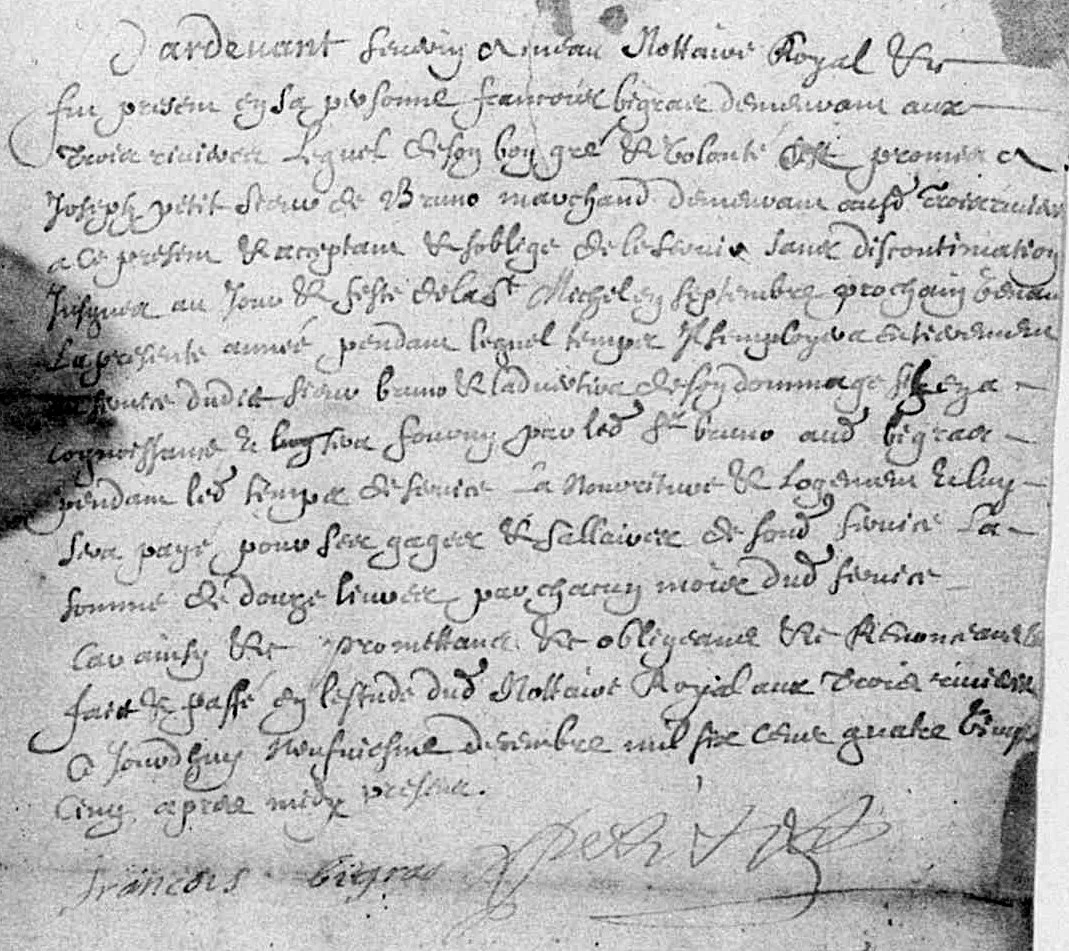

Although the contract followed the Coutume de Paris, it was brief and made no mention of postponing the marriage until Marie reached legal age. Instead, her parents promised to house and feed her for one year after the wedding. François did not provide a dower but agreed to deliver twelve minots of wheat to the Brunets in its place.

Legal Age to Marry

In New France, the legal minimum age for marriage was 14 for boys and 12 for girls. These requirements remained in effect through the eras of Lower Canada and Canada-East. In 1917, the Catholic Church revised its code of canon law, setting the minimum age at 16 for men and 14 for women. The Code civil du Québec later raised the age to 18 for both sexes in 1980. At all times, minors required parental consent to marry.

Portion of the 1685 marriage contract between François Bigras and Marie Brunet (FamilySearch)

Though François was bound by contract to notary Séverin Ameau until 1687, he signed another agreement on December 9, 1685, to work for Joseph Petit de Bruneau, a merchant in Trois-Rivières, until the feast of Saint-Michel (September 29) in 1686. He was described as a resident of Trois-Rivières and was to receive twelve livres per month, along with food and lodging. The document was drawn up by Ameau himself, suggesting that he either released François from his earlier contract or permitted him to serve both men simultaneously.

1685 work contract between François and Joseph Petit de Bruneau (FamilySearch)

In early 1686, at just twenty, François was back in Québec. On February 22, notary Gilles Rageot recorded an obligation in which François acknowledged owing 71 livres and 7 sols to Québec merchant Simon Jarent, an associate of Petit. He was described as a laboureur volontaire (a farmer working on his own account) of Québec. François promised to repay the debt from wages earned on an upcoming voyage to the north. This is the first record linking him to the fur trade, although no surviving contracts detail the expedition itself.

For the next several years, François likely worked and travelled on fur trade ventures, though records of his activities in the late 1680s and early 1690s are scarce. He may have operated as a coureur des bois rather than as a licensed voyageur.

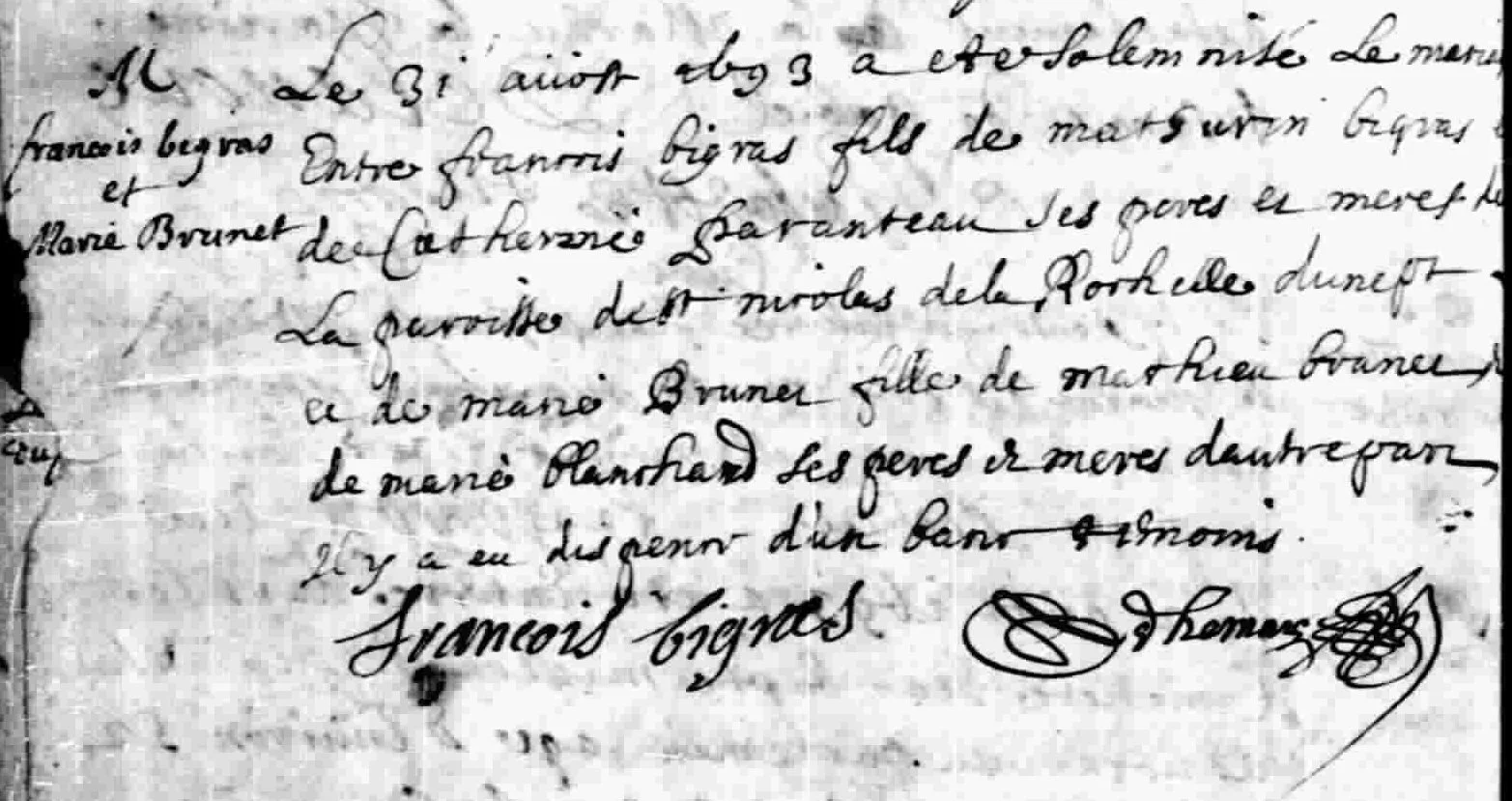

Marriage in Montréal

On August 31, 1693, eight years after their marriage contract was signed, François Bigras and Marie Brunet were married in the parish of Notre-Dame in Montréal. François was 27 years old, and Marie was 15. He was able to sign the marriage record, but she was not. The entry does not list any witnesses.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

1693 marriage of François Bigras and Marie Brunet (Généalogie Québec)

A Home in Lachine

François and Marie settled in Lachine, a strategic location near Montréal that served as a departure point for western fur routes. They had 13 children, 12 of whom survived to adulthood and married:

Marie Louise (1694–1772)

Jacques (1696–1751)

Marie Françoise (1698–1778)

François (1700–1781)

Marguerite (1701–1778)

Marie Angélique (1703–1791)

Alexis (1705–1791)

Joseph (1707–1781)

Judith (1709–1755)

Marie Anne (1711–1793)

Geneviève (1714–1766)

Antoine (ca. 1716–aft. 1734)

Marie Madeleine (1719–1722)

On his children’s baptism records, François was described as an habitant (1696) and as a ploughman (1700).

Voyageur in the Fur Trade

On September 19, 1694, François reportedly agreed to work as a voyageur for Laforest and Tonty, though the original contract has not been located.

On July 16, 1695, he signed a voyageur contract with Antoine Trottier dit Desruisseaux, a Batiscan merchant. He agreed to travel by canoe to Katarakouy to trade merchandise for furs. Katarakouy (or Cataracoui) was the French name for the fort and settlement at present-day Kingston, Ontario—originally Fort Frontenac—built at the mouth of the Cataraqui River on Lake Ontario. A canoe voyage, typically crewed by four to six men, took about ten days to reach Katarakouy.

In August 1696, François sued merchant Jacques Aubuchon dit Desalliers over a fur trade expedition. The surviving judicial file records an order to summon witnesses; the outcome is unknown.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

Land Purchase & Exchange

On the afternoon of May 5, 1697, François purchased land from Jean Danis and Anne Badel for 60 livres. The property, located on coteau Saint-Pierre, measured three arpents wide by 20 deep. It bordered the lands of Antoine Pilon and Pierre Sabourin, the Saint-Pierre River, and non-ceded land. François agreed to pay six deniers in cens annually and one and a half minot of wheat in rente, payable on the feast day of Saint-Martin.

On the same day, François and Marie entered into a constitution de rente annuelle et perpétuelle with Pierre Rémy, Sulpician priest of the parish of Saints-Anges in Lachine. In exchange for 63 livres—provided as 15 cards worth four livres each, one two-livres card, and one one-livre card—they agreed to pay him a perpetual annuity of three livres and three sols, secured on their property.

On June 22, 1701, François and Marie exchanged their land in côte Saint-Pierre for one in Grande Ance belonging to Jean Boisson dit Saintonge and Marie Legros. The parcels were equal in area (60 arpents). Their new land bordered Lac Saint-Louis, non-ceded land, and the properties of Mathurin Chartier dit Lamarche and Mr. Pomainville. The annual cens was 30 sols, and the rente one and a half minot of wheat.

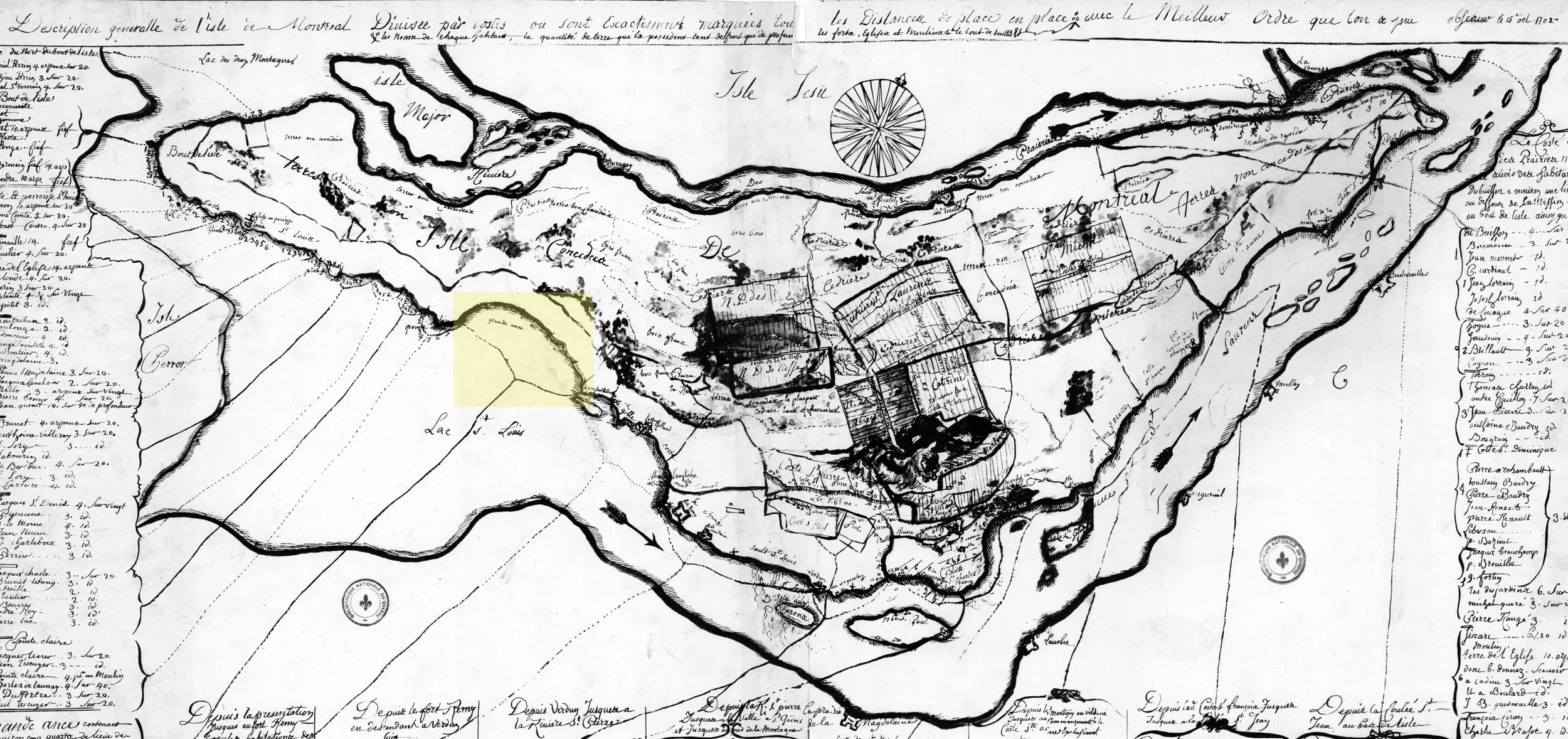

“General description of the island of Montreal divided into sections,” 1702 map by François Vachon de Belmont, with Grande Ance in yellow (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

On October 17, 1710, François and Marie signed a work contract for their 12-year-old daughter, Marie Françoise, to work as a general servant for Claude Maurice dit Lafantaisie and Marie Madeleine Dumouchel in Montréal. A few months later, on December 3, François and Marie sold her inheritance rights to movable and immovable property to Honoré Danis, likely in exchange for a sum of money. [The notary’s handwriting is extremely difficult to read.]

François’s signature in 1710 (FamilySearch)

From Voyageur to Trader

By the 1710s, François was past the age to work as a voyageur himself. Instead, three notarial records show him organizing and financing trading expeditions—acting, in effect, as a small-scale merchant.

On September 19, 1713, he and his associate Paul Chevalier hired Charles Parent as a voyageur for one paddling season. Parent agreed to travel to “the Detroit of Lake Erie” with a canoe filled with merchandise and return with one filled with furs. He was promised 150 livres in wages upon his return, plus food.

On May 25, 1714, François and two partners, Paul Bouchard and Jean Cotton dit Fleurdespé, hired Pierre Sabourin for a similar venture to Michilimackinac. Sabourin agreed to take a canoe loaded with merchandise to the post and return with one filled with furs. He was promised food, a gun, and 200 livres upon his return. Such partnerships were common for long expeditions: investors shared costs (trade goods, canoe, provisions, advance pay) and divided returns in furs.

Michilimackinac referred to the remote French fort and mission at the Straits of Mackinac (today Mackinaw City, Michigan), the meeting point of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. Founded in the 1670s by the Jesuits and later fortified, it was a major hub of the western fur trade by 1715 — linking Montréal to the Great Lakes and the Pays d’en haut.

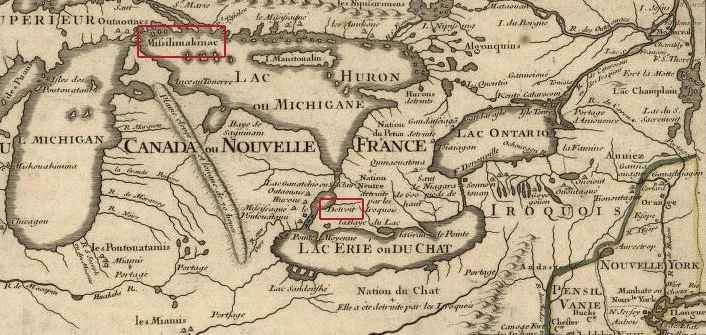

“Map of Louisiana and the course of the Mississippi River: drawn up based on a large number of memoirs, including those of Mr. le Maire,” 1718 map by Guillaume de L’Isle, with Detroit and Michilimackinac in red (Library of Congress)

On October 16, 1715, notary Jean Baptiste Adhémar de Saint-Martin recorded that François paid a debt of 97 livres and 18 sols to Françoise Nafrechou, wife of Jacques Pommereau, and received a quittance (receipt).

The Next Generation

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

Four of François’s sons also became voyageurs: Jacques, François, Alexis, and Joseph.

Jacques made at least two trips to Michilimackinac (1727, 1736) and at least five trips to Detroit (1717–1742). He later settled in Detroit, where he died on February 4, 1751.

François travelled three times to Michilimackinac (1732–1739), once to Detroit, and once to the Pays d’en haut, a vast territory encompassing most of the Great Lakes.

Alexis made one trip to Michilimackinac in 1744.

Joseph travelled to the Pays d’en haut in 1728 and to Michilimackinac in 1738.

On April 12, 1718, François received a land concession from the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Montréal, seigneur of the island of Montréal. The property, located on côte Saint-Rémy behind Grande Ance, measured three arpents of frontage by 20 deep. François agreed to have his grain ground at the seigneurial mill, to build a dwelling and live on the land within one year, and to keep the main common road of côte Saint-Rémy clear and passable. The annual rente was set at ten sols and half a minot of wheat for each 20 arpents, plus seven sols and six deniers in cens, all payable on the feast of Saint-Martin. The seigneurs also reserved the right to take wood for construction and heating from the land as needed.

On June 8, 1725, François received another concession at côte Saint-Rémy from the Sulpicians. This “remaining piece of land” measured about 40 arpents. As before, the annual rente was fixed at ten sols and half a minot of wheat for each 20 arpents.

The final mention of François in notarial records before his death dates to February 5, 1729. He was then recorded as an habitant of côte Saint-Rémy aux Sources. On that day, he acknowledged owing 100 livres to merchant Pierre Courraud de Lacoste for merchandise already delivered for his household’s needs and subsistence. He promised repayment by August 1729 without guarantors, pledging all present and future property as security. Payment could be made, at Lacoste’s choice, in beaver pelts at the official bureau price, other good furs at the outfitter’s price, or cash. Should he default, François accepted liability for legal costs, damages, and interest, and allowed for the seizure of both movable and immovable property. Curiously, the record states that François declared he did not know how to read or write, despite the many signatures he had placed on earlier documents.

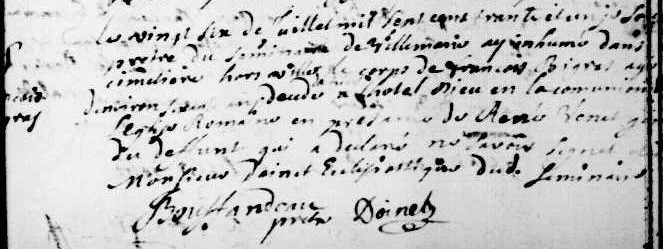

Death of François Bigras

François Bigras died at age 65 at the Hôtel-Dieu in Montréal. He was buried in the “cemetery outside the town,” with his son-in-law René Venet present at the burial.

1731 burial of François Bigras (Généalogie Québec)

Following his death, a meeting of relatives and friends was convened to elect a guardian and substitute guardian for François and Marie’s minor children. On March 29, 1732, their eldest son Jacques was chosen as guardian. [Although the court record refers only to the meeting and not the final decision, Jacques is named guardian in subsequent documents. The same record also mentions that an inventory was drawn up after François’s death, but it could not be located.]

In January 1733, Jacques—acting both on his own behalf and as guardian of the minor children—initiated proceedings before the royal jurisdiction of Montréal. The case concerned the licitation, or court-ordered sale, of land belonging to François and Marie, with the goal of liquidating assets to settle debts and distribute the estate among heirs and creditors.

The court first issued a sentence authorizing the sale, with a short delay for adjudication. Almost immediately, several creditors filed oppositions concerning the division of the estate. Among them were Jacques Gadois dit Mauger, who contested how the proceeds should be distributed; Paul Bouchard, acting on behalf of the religious sisters of the Hôtel-Dieu; and Gabriel Lenoir dit Roland, who also sought payment. To manage these claims, Jacques’s attorney, René Aubin, petitioned the court to assemble the opposing creditors. Aubin later submitted his own account of legal services rendered and confirmed that the parish priest of Pointe-Claire, Father Breul, had been paid through the intermediary Jean Létang.

As the case proceeded, the court examined a statement of debts that François Bigras had made to Father Breul before his death, including obligations such as unpaid tithe, and also considered claims from other creditors, such as Volant, sieur de Radisson. The process culminated in a sentence d’ordre, a formal ruling that organized the payment of creditors out of the proceeds from the land sale. Additional sentences were rendered: one dealt specifically with Jacques Gadois’s demand that he be reimbursed by the deceased’s son, François; another ordered the heirs to provide their widowed mother, Marie, with a regular pension for her maintenance.

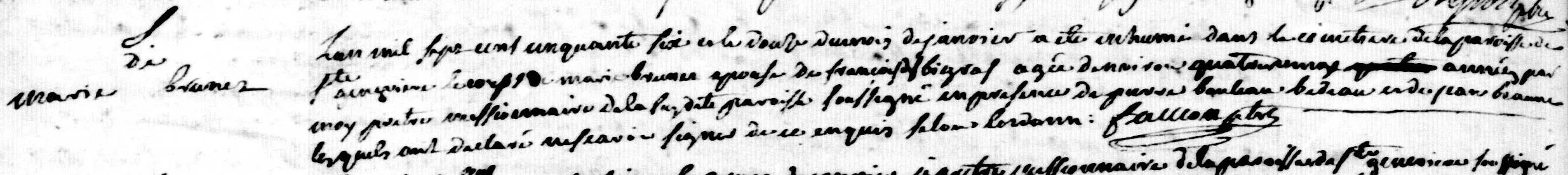

Death of Marie Brunet

Marie outlived her husband by 25 years. She died at age 78 and was buried on January 12, 1756, in the parish cemetery of Sainte-Geneviève in Pierrefonds.

1756 burial of Marie Brunet (Généalogie Québec)

A Family Shaped by the Fur Trade

François Bigras arrived in New France as a teenager, drawn by the same spirit of adventure that had brought his aunts across the Atlantic a generation earlier. Literate and ambitious, he embraced the opportunities of the colony—signing work contracts, taking on land concessions, and venturing into the fur trade as both voyageur and trader. His journeys carried him along the major waterways of the colony, from Québec to Michilimackinac and Detroit, where furs and goods flowed between Indigenous nations and French merchants.

Yet his adventurous life came with risks. The debts he incurred over the years ultimately weighed heavily on his estate and forced his widow and sons to answer for obligations he left behind. Court proceedings after his death revealed the extent of these financial burdens, underscoring the precarious balance between enterprise and hardship in colonial New France.

Despite these challenges, François left a lasting legacy. Four of his sons followed in his footsteps as voyageurs, carrying the Bigras name deep into the Great Lakes and the Pays d’en haut. Through them, the spirit of adventure that had inspired a young boy from La Rochelle continued to shape the family’s story for generations.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"G G 378 La Rochelle > Baptêmes > Paroisse Saint-Nicolas > 1654 -1667," digital images, Archives départementales de la Charente-Maritime (http://www.archinoe.net/v2/ark:/18812/2454f0cae617c3b25ade200191456844 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), baptism of François Bigras, 8 Sep 1665, La Rochelle (St-Nicolas).

"G G 379 La Rochelle > Mariages > Paroisse Saint-Nicolas > 1654 -1667," digital images, Archives départementales de la Charente-Maritime (http://www.archinoe.net/v2/ark:/18812/81e1b5f4fef337e8ef2e48004e8e3970 : accessed 8 Aug 2025), marriage of Mathurin Bigras and Catherine Parenteau, 19 Sep 1660, La Rochelle (St-Nicolas).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/69435 : accessed 8 Aug 2025), burial of Louis Moreau, 15 Jan 1683, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec); citing original data: Collection Drouin, Institut Généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/5914 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), baptism of Marie Brunet, 26 Oct 1677, Cap-de-la-Madeleine (Ste-Marie-Madeleine).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/47597 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), marriage of François Bigras and Marie Brunet, 31 Aug 1693, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/150760 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), burial of François Bigras, 26 Jul 1731, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/281436 : accessed 18 Aug 2025), burial of Marie Brunet, 12 Jan 1756, Pierrefonds (Ste-Geneviève).

“Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-J3DQ-JC2Q?cat=1171570&i=3199&lang=en : accessed 8 Aug 2025), work contract between Louis Moreau and François Bigras, 14 Jul 1682, image 3,200 of 3,381; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NF-49H3-H?cat=1171570&i=574&lang=en : accessed 8 Aug 2025), land concession to François Bigras, 2 Oct 1684, images 575-576 of 1,327.

“Actes de notaire, Pierre Duquet de la Chesnaye (1663-1687), digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/5044560?docref=wj2AKUDr1nAXbhK--LvY_A : accessed 8 Aug 2025), work contract between Madeleine Boudouin and Séverin Ameau de St Séverin, and François Bigras, 6 Nov 1684, image 122 of 653.

“Actes de notaire, 1677-1696 // Claude Maugue,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-93W6-5?cat=427707&i=1181&lang=en : accessed 8 Aug 2025), marriage contract of François Bigras and Marie Brunet, 25 Aug 1685, images 1,182-1,183 of 3,150; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1651-1702 // Ameau Séverin,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-73JY-9?cat=615650&i=1928&lang=en : accessed 14 Aug 2025), work contract between François Bigras and Joseph Petit de Bruno, 9 Dec 1685, image 1,929 of 2,436; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NF-498H-Y?cat=1171570&i=1125&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), obligation of François Bigras to Simon Jarent, 22 Feb 1686, image 1,126 of 1,327; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-MWNV-Q?cat=541271&i=209&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), work contract between François Bigras and Antoine Trotier-Desruisseaux, 16 Jul 1695, image 210 of 2,856; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1686-1701 // Jean-Baptiste Pottier,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3VW-V93S-D?cat=529326&i=1403&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), land sale by Jean Dany and Anne Badel to François Bigras, 5 May 1697, images 1,404-1,405 of 3,207; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1686-1701 // Jean-Baptiste Pottier,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3VW-V93W-N?cat=529326&i=1406&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), establishment of an annual and perpetual annuity by François Bigras and Marie Brunet, to Pierre Remy, 5 May 1697, images 1,407-1,408 of 3,207.

“Actes de notaire, 1697-1727 // Pierre Raimbault,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5V-SSP8?cat=675517&i=1914&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), land exchange between François Bigras and Marie Brunet and Jean Boisson dit Xaintonge and Marie Legros, 22 Jun 1701, images 1,915-1,917 of 3,137; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-2B34?cat=541271&i=2330&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), work contract of Françoise Bigras, 17 Oct 1710, image 2,331 of 3,055.

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-2B47?cat=541271&i=2437&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), sale of inheritance rights by François Bigras and Marie Brunet to Honoré Danis Bigras, 3 Dec 1710, images 2,438-2,439 of 3,055.

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-B9NV-K?cat=541271&i=1094&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), hiring of Charles Parent as a voyageur by Paul Chevalier and François Bigras, 19 Sep 1713, image 1,095 of 3,080.

“Actes de notaire, 1714-1754 // Jean-Baptiste Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-FS5Q-V?cat=679139&i=2560&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), hiring of Paul Sabourin as a voyageur by Paul Bouchard, François Bigras and Jean Cotton dit Fleurdespé, 25 May 1714, images 2,561-2,562 of 3,158; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1714-1754 // Jean-Baptiste Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-FSLY-8?cat=679139&i=3072&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), receipt from Françoise Nafrechou to François Bigras, 16 Oct 1715, image 3,073 of 3,158.

“Actes de notaire, 1697-1727 // Pierre Raimbault,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5V-4SR6-9?cat=675517&i=2551&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), land concession to François Bigras, 12 Apr 1718, images 2,552-2,554 of 3,060.

“Actes de notaire, 1697-1727 // Pierre Raimbault,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5V-W7NS-F?cat=675517&i=3027&lang=en : accessed 15 Aug 2025), land concession to François Bigras, 8 Jun 1725, images 3,028-3,030 of 3,089.

"Actes de notaire, 1727-1752 // Nicolas-Augustin Guillet de Chaumont," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-G3VH-L?cat=481199&i=1233&lang=en : accessed 18 Aug 2025), debt owed by François Bigras to Pierre Courraud de Lacoste, 5 Feb 1729, images 1,234-1,235 of 3,195.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 15 Aug 2025), "Engagement de François Bigras, voyageur, à de Laforest et de Tonty," notary A. Adhémar de Saint-Martin, 19 Sep 1694.

“Fonds Cour supérieure. District judiciaire de Montréal. Tutelles et curatelles - Archives nationales à Montréal," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/473801 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), "Tutelle des enfants mineurs de feu François Bigras et de Marie Brunet [Létang]," 29 Mar 1732, reference C601,S1,SS1,D767, Id 473801.

“Fonds Juridiction royale de Montréal - Archives nationales à Montréal," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/702050 : accessed 18 Aug 2025), "Licitation d'une terre appartenant au défunt François Bigras et à son épouse Marie Brunet, de Pointe-Claire, à la requête de Jacques Bigras, en son nom et comme tuteur des enfants mineurs de son défunt père," 13 Jan 1733-25 Feb 1734, reference TL4,S1,D3994, Id 702050.

"Fonds Juridiction royale de Montréal - Archives nationales à Montréal," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/697207 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), "Procès entre François Bigras, demandeur, et Jacques Aubuchon dit Desalliers, défendeur, concernant un voyage de traite," 29 Aug 1696, reference TL4,S1,D172, Id 697207.

Centre du patrimoine, Voyageur contract database (https://shsb.mb.ca/contrats-des-voyageurs/ : accessed 15 Aug 2025).

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/bigras/-bigreau/-fauvel accessed 8 Aug 2025), entry for François BIGRAS / BIGREAU / FAUVEL (person #240379), updated on 4 Oct 2010.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/7073 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Francois BIGRAS and Marie BRUNET LETANG, union 7073.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/4869 : accessed 15 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques BIGRAS FAUVEL, person 4869.

Jacqueline Sylvestre, "L’âge de la majorité au Québec de 1608 à nos jours," Le Patrimoine, Feb 2006, volume 1, number 2, page 3, Société d’histoire et de généalogie de Saint-Sébastien-de-Frontenac.