Nicolas Perrot & Marie Madeleine Raclos

A famous explorer, negotiator and interpreter, Nicolas Perrot is well-entrenched in Canada’s history books. But the story of his life, and that of his wife Madeleine Raclos, was also one of hardship. Nicolas spent most of his life in poverty, unable to complete his memoirs because he could not afford to buy more paper. Madeleine struggled with mental illness. This is the story of celebrated accomplishments, their struggles, and the important legacy they left behind.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Nicolas Perrot & Marie Madeleine Raclos

A famous explorer, negotiator and interpreter, Nicolas Perrot is well-entrenched in Canada’s history books. But the story of his life, and that of his wife Madeleine Raclos, was also one of hardship. Nicolas spent most of his life in poverty, unable to complete his memoirs because he could not afford to buy more paper. Madeleine struggled with mental illness. This is the story of celebrated accomplishments, their struggles, and the important legacy they left behind.

Nicolas Perrot, son of François Perrot and Marie Sirot (or Sivot), was born around 1644 in Darcey, Bourgogne, France (in the present-day department of Côte-d'Or). Located about 50 kilometres northwest of Dijon, today Darcey is a small rural commune of less than 350 residents.

Nicolas' father worked as a "lieutenant of justice" in Darcey.

Location of Darcey (map data ©2022 Google)

The 12th-century Church of St-Bénigne (Wikimedia author Pethrus)

“Donné” of the Jesuits

By 1660, Nicolas was in New France, employed as a donné by the Jesuits. (A donné was a lay person who would assist the Jesuits in converting the natives to Roman Catholicism.) As he visited various indigenous peoples with the priests, Nicolas learned to speak multiple languages. Within three years, he was living among the Indigenous peoples of Wisconsin, still working for the Jesuits. By 1665, Nicolas had reportedly left the employ of the Jesuits, his initial engagement contract likely over. That year, he visited the Potowatami and Fox tribes, before making his way to Montréal.

In 1666, Nicolas was recorded in the New France census living in Montréal. He was enumerated as the 22-year-old domestic servant of Marie Pournin, the widow of Jacques Tetard.

1666 census for the household of Marie Pournin (Library and Archives Canada)

A year later, 26-year-old Nicolas was still living in Montréal, but working as a servant of the Sulpician priests. In their employ, he also worked as a donné. (Ages reported on census records are notoriously unreliable, as evidenced here.)

1667 census entry for Nicolas Perrot (Library and Archives Canada)

The Fur Trade

1718 map of the Michigan region and the Baie des Puants in the era of New France by Guillaume Delisle (Library of Congress)

The opportunities presented by the fur trade soon became apparent to Nicolas. In 1667, he formed a company with three other men who were interested in trade and exploration in the Wisconsin area. A year later, Nicolas travelled through the villages of Winnebago, Potowatami, Fox and Sauk near the Baie des puants (present-day Green Bay), trading for furs. He was often the first Frenchman to come into contact with these first nations. This was the beginning of Nicolas' celebrated career as an explorer, fur trader and interpreter.

In June of 1670, Nicolas was back in Montréal. He was immediately summoned to Québec by Governor Daniel Rémy de Courcelles and Intendant Jean Talon. Nicolas, along with Daumont de Saint-Lusson, agreed to travel to Wisconsin. Their objective was to assemble representatives of western indigenous nations and formalize an alliance with the King of France, with Nicolas acting as the guide and interpreter. Before leaving, Nicolas formed another commercial company with five men on September 2, 1670. About a month later, Nicolas and Saint-Lusson were paddling down the Ottawa River with a view toward Wisconsin. They reached the northern shore of Lake Huron and the Amikoués people, where they remained for the winter. Once the ice had thawed, the pair set off again, reaching Sault Sainte-Marie in May of 1671. There, on June 14, 1671, a ceremony took place to officialize the possession of western lands by the King of France, with the approval of 14 indigenous nations. Nicolas signed the agreement in his capacity as official interpreter.

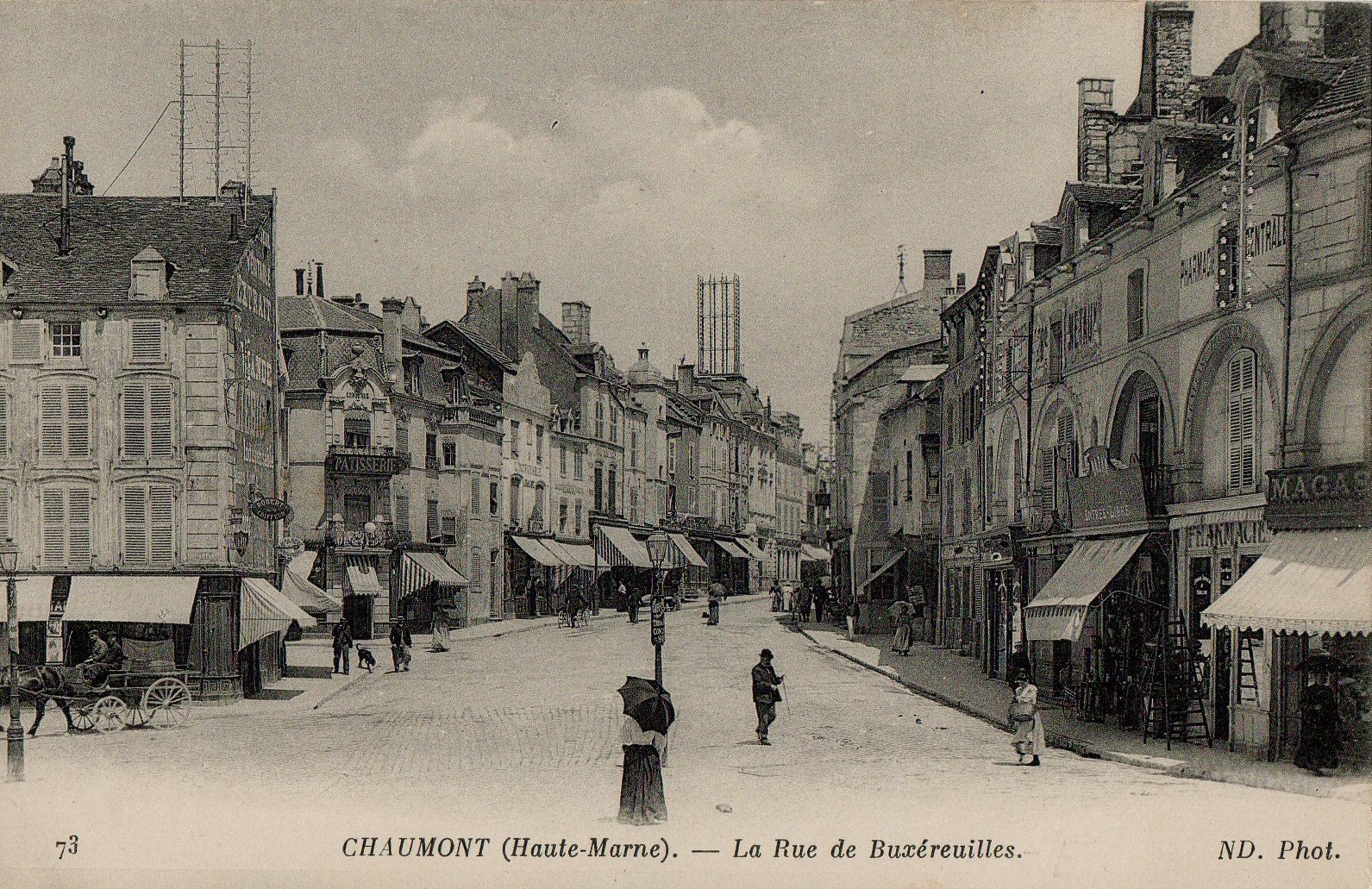

Marie Madeleine Raclos, daughter of Bon Raclos (or Raclot) and Marie Vienot, was baptized on January 8, 1656, in the parish of St-Jean-Baptiste in Chaumont-en-Bassigny, Champagne, France (present-day Chaumont in the department of Haute-Marne).

1656 Baptism of Marie Madeleine Raclos (Archives départementales de la Haute Marne)

Location of Chaumont-en-Bassigny, France (map data ©2022 Google)

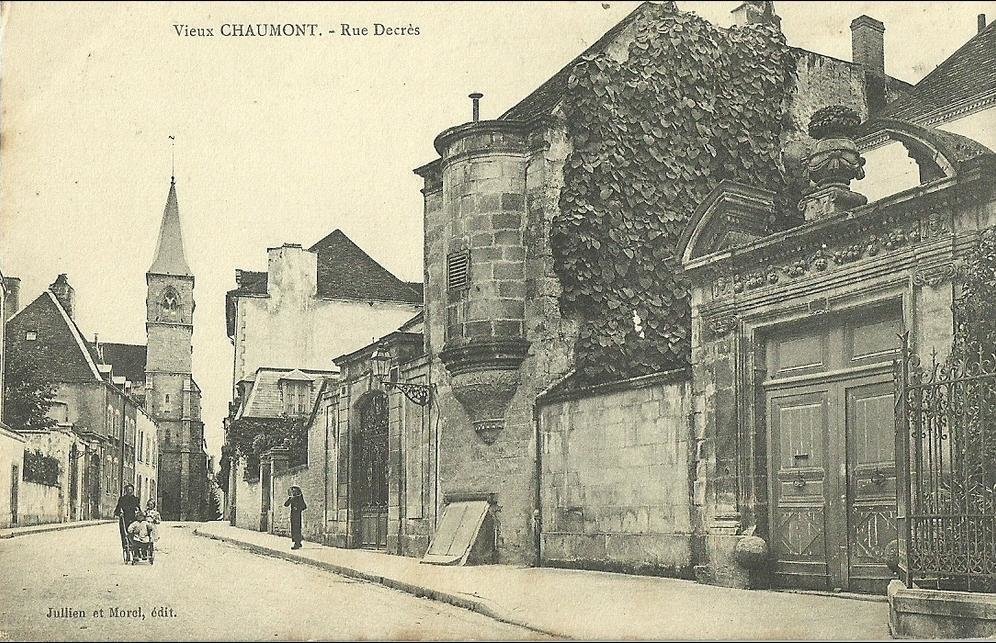

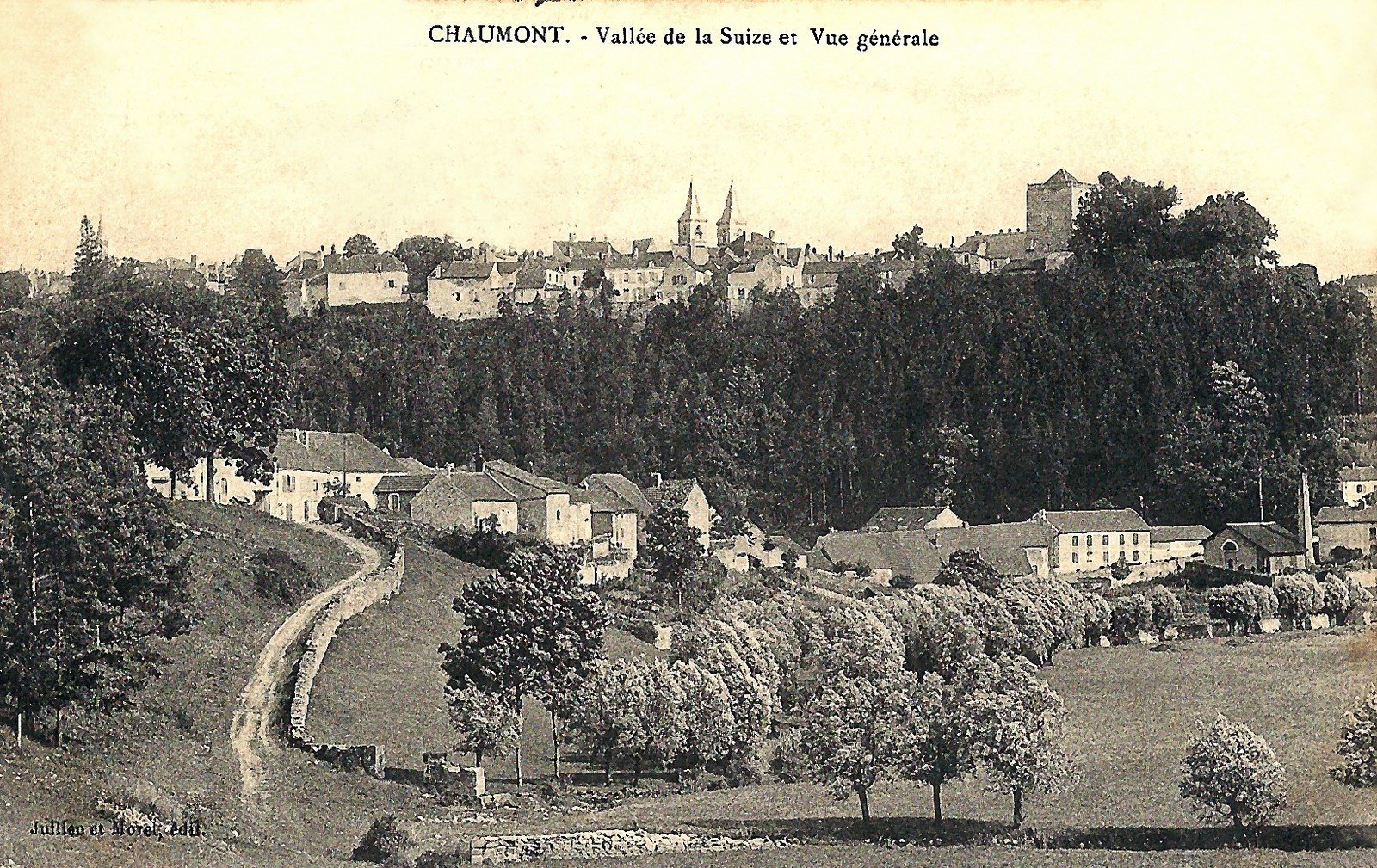

Undated postcards of Chaumont-en-Bassigny (Geneanet)

Marie Madeleine arrived in Québec aboard the St-Jean Baptiste on August 15, 1671, with her father and two sisters, Marie and Françoise. Bon Raclos returned to France sometime after October 17, 1672. All three daughters had a 1,000-livre dowry, an amount considerably higher than the average dowry at the time. Their father was a successful merchant in the tanning industry.

Fille du roi?

An overly romanticized portrait of les Filles du roi arriving at Québec ("Women coming to Québec in 1667, in order to be married to the French Canadian farmers", watercolour by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale)

The Filles du roi were a group of some 700 unmarried women who were sent to New France between 1663 and 1673 by King Louis XIV to solve a gender imbalance problem, and ultimately help to populate the new colony. They were called “daughters of the king” because Louis XIV paid for their recruitment, clothing and passage to the new world and offered dowries to the women when they married. The filles du roi represent half of the women who immigrated to New France early in the colony's history.

The Raclos daughters were initially qualified as filles du roi because some accounts had mistakenly stated that their father had simply accompanied them to Québec and returned to France a few months later. This has been proven false through notarial records placing Bon Raclos in the colony over a year later. Two of the daughters also received "the king's gift" at their marriage, but this money wasn't uniquely provided to the filles du roi. Though Bon Raclos did return to France, this does appear to be a case of family migration. The Raclos daughters are not included in the Filles du roi list from the Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) of the Université de Montréal.

Marriage

On November 11, 1671, Nicolas and Marie Madeleine appeared before notary Guillaume de Larue in Champlain to have their marriage contract drawn up. Nicolas was about 27 years old; Marie Madeleine was 15. Both were able to sign the contract, as was Madeleine's father. Both her sisters were also present. (The actual marriage record no longer exists, but the ceremony normally took place within 3 weeks of the marriage contract being signed).

Extract of the marriage contract of Nicolas Perrot and Marie Madeleine Raclos in 1671 (kept at the Séminaire de Québec; the original no longer exists)

Legal Age to Marry

In order to marry in the time of New France, a groom had to be at least 14 years old, while a bride had to be at least 12. In the era of Lower Canada and Canada-East, the same requirements were in place. The Catholic church revised its code of canon law in 1917, making the minimum age of marriage 16 for men and 14 for women. In 1980, the Code civil du Québec raised the minimum age to 18 for both sexes. Furthermore, minors needed parental consent in order to marry. In New France, the age of legal majority was 25. Under the British Regime, it was changed to 21. Since 1972, the age of majority in Canada has been set at 18 years old.

Voyageur

Nicolas seemingly wasn't willing to stay put for very long. In September of 1672, he received a "congé de traite" from Governor Frontenac, allowing him to travel up the Ottawa River in a canoe loaded with merchandise to trade for furs. He worked as a "coureur des bois" until 1683, travelling to the Great Lakes every summer, always expanding his network of indigenous connections. After the trade of the coureur des bois was deemed illegal by French authorities, Nicolas became a licensed "voyageur".

“Canoe Manned by Voyageurs Passing a Waterfall,” 1869 oil painting by Frances Ann Hopkins (Library and Archives Canada)

In 1677, Nicolas obtained a land concession from Charles Pierre Legardeur de Villiers at the Rivière Saint-Michel-de-Bécancour.

The Perrot family was enumerated in the 1681 New France census living in the seigneurie de Lintot (also called Linctot), on the south shore of the Saint-Lawrence River. Nicolas owned two guns, five heads of cattle and 18 arpents of land. The seigneurie was located in present-day Bécancour.

1681 census entry for the Perrot family (Library and Archives Canada)

Western Travels & Exploration

In 1685, Nicolas was named commander in chief of the Baie des puants and surrounding area, commonly called the Pays d'en Haut. Before leaving, he signed a procuration in favour of his wife Madeleine, so she could act as a proxy in his absence. Nicolas was tasked with yet another mission in Wisconsin, this time to convince the western indigenous nations to fight the Iroquois (today called the Haudenosaunee people) alongside the French. Accompanied by about 20 men, Nicolas paddled up the Ottawa River yet again on route to Baie des puants. Once there, he learned that the Sioux and Chippewas were in conflict with the Fox nation. Peace was required if Nicolas was going to rally all of these tribes to the French cause. The conflict had escalated when the Fox kidnapped the daughter of a Sauk chief. Nicolas and his men managed to free the girl and return her to her father, obtaining a promise from him that he would not retaliate. While in Wisconsin, Nicolas also gifted the St-François-Xavier Catholic mission chapel with a silver ostensorium.

With peace re-established, Nicolas sent the Puants to travel the western shore of the Mississippi River. He followed them up the river, passed Prairie-du-Chien and La Crosse (both in Wisconsin), then camped near Lake Pepin (between Wisconsin and Minnesota). There he and his team constructed Fort-Saint-Antoine.

1688 map by Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin, showing Fort Saint-Antoine (Library of Congress). This map drawn by Franquelin was largely based on the information Nicolas provided him.

In 1687, new orders came from Québec—Nicolas was to abandon the fort and travel to Niagara to fight the Onandaga, with as many indigenous allies as possible. At the Jesuits' mission of St-François-Xavier, he left behind all the wealth he had amassed in pelts, believing they would be safe in the Jesuits' barn until his return. Nicolas and his men made their way to Detroit, destroying five Onandaga villages.

Financial Ruin

While Nicolas was away, conflict erupted again in Baie des puants. Relations between the French and indigenous nations there weren't as peaceful as he had hoped. Upset with the French, a group of indigenous men burned down the Jesuits' home, church and barn. The fire completely gutted the mission of St-François-Xavier, burning with it all of Nicolas' belongings and furs. He was financially ruined, the burnt furs reportedly worth 40,000 livres.

Nicolas returned to Bécancour, having been away from his wife and family for over two years. His work as an interpreter soon called him back to Montréal, where he participated in treaty negotiations with the Onandagas, Cayugas and Oneidas in 1688.

Despite his troubled financial situation, Nicolas purchased the seigneurie of Rivière-du-Loup (present-day Louiseville) from Jean Le Chasseur, lieutenant general of Trois-Rivières and counsellor to the king, for 4,000 livres in beaver pelts in May of 1688. This made him a "seigneur", at least for a few years. Several court documents show that Nicolas was unable to make the payments he had agreed to. On November 24, 1698, he was ordered to pay Le Chasseur 1,400 livres in beaver pelts, interest in the amount of 4,000 livres in pelts, plus 385 livres for labour. The sale of the seigneurie was declared null and void, and Le Chasseur was allowed to take possession of the land.

Nicolas was soon on his way to Wisconsin again, tasked with building Fort Saint-Nicolas (near Prairie-du-Chien) and taking possession of la Baie des puants, as well as the Outaganis and Mascouten's lakes and rivers in the name of Louis XIV. As of May 8, 1689, the Upper Mississippi was under French rule thanks to Nicolas, seemingly with the consent of the Fox, Potowatami, Chippewa, Sauk, Winnebago and Menominee nations. Click here to see a map of Nicolas' travels.

Nicolas made multiple trips to the west, always seeking to further France's interests and his own personal interests in the fur trade. Dozens and dozens of notarial records provide evidence of his involvement in the trade, many of them engagement contracts for the men working for him.

The Great Peace of Montréal

"La paix de Montréal" (The peace of Montréal), painting by Jean-Baptiste Lagacé (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In 1696, Nicolas returned to his home in Bécancour, leaving his voyageur days behind. His skills as an interpreter, however, were still sought out by the colony's administrators. During the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701, Nicolas served as an interpreter for Governor de Callières and the western nations.

Excerpt from the copy of the Treaty of the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701 (Wikimedia Commons)

Memoir

During the following decade, Nicolas wrote a memoir of his time among indigenous peoples. Entitled Mémoire sur les mœurs, coustumes et religion des Sauvages de l'Amérique Septentrionale, it was published in Paris in 1864. It was a rushed biography, however. In its last pages, Nicolas wrote that he was unable to write a more complete history, as he had run out of paper. (The memoir is available at Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec and Bibliothèque nationale de France.)

In 1708, Nicolas accepted the role of militia captain in the côte of Bécancour.

For the last two decades of his life, Nicolas was brought before the courts on a regular basis by creditors. He was never able to recuperate from the financial tragedy that befell him in Wisconsin. His financial situation became more complicated when his wife Madeleine learned of a 2,000-livre inheritance she was to receive from her aunt Colette Raclos in Paris. After seeking legal advice, Marie Madeleine petitioned the court in 1702 for a separation of property between her and her husband, which would have allowed her to collect her inheritance without the fear of creditors coming after her. Champlain’s priest, Pierre Hazeur Delorme, offered to sail to Paris and collect the amount for Madeleine. On his return, he demanded a 50% commission of the amount. This incident led to even more appearances before the courts. In 1715, the Sovereign Council ordered Delorme to pay Madeleine and Nicolas 5,411 livres for the amounts he owed them.

Seven Sons and Four Daughters

Though he was absent from his wife for long periods of time, Nicolas had a large family. He and Marie Madeleine had eleven children:

Marie Madeleine Perrault (or Perrot) (1683-1683)

Claude Perrault (or Perrot) (1684-1741)

Pierre Perrault (or Perrot) (ca. 1686-1725)

Jean Baptiste Perrault (or Perrot) (1688-1705)

Jean Perrault (or Perrot) (1690-1773)

François Perrault (or Perrot) (ca. 1672-?)

Nicolas Perrault (or Perrot) dit Turbal (ca. 1674-?)

Marie Clémence Perrault (or Perrot) (ca. 1676-1756)

Michel Perrault (or Perrot) (1677-1723)

Marie Françoise Perrault (or Perrot) (1678-1744)

Marie Anne Perrault (or Perrot) (1680-1745)

Death of Nicolas Perrot

Nicolas Perrot died at the age of about 73 on August 13, 1717. He was buried the following day inside the church of Bécancour.

1717 burial record for Nicolas Perrot (Ancestry)

Buried inside the church?

Intramural church burials are an ancient Christian tradition that early colonists brought from France. French tradition dictated that the privilege was mainly reserved for clergy and nobles. In New France, however, we find that burials within church walls were not restricted to this group of elites. They were performed for those belonging to the most powerful social groups (which could even include farmers), those who were most successful in their trade and those who were committed to their church and community. Bodies were placed in the crypt (or cellar) located under the floor of the church, or in a grave dug after raising the floor or a church bench. The funeral rites that accompanied such a burial were generally more elaborate and expensive than those performed for a cemetery burial. The practice of intramural church burials disappeared from most parishes by the mid-nineteenth century, mainly due to public hygiene concerns and a lack of space.

A Sad End for Madeleine

After her husband's death, Marie Madeleine's mental health started to decline. Her multiple appearances before the courts to secure her inheritance had caused her severe stress.

On October 18, 1717, she purchased a plot of land in St-Sulpice from Pierre Gour and Catherine Richome, where many of her children were living. Her son Pierre acted as her proxy. Perhaps due to declining health, Marie Madeleine never moved to St-Sulpice. On August 12, 1719, she gathered her children in Trois-Rivières and gave them all of her property: the land in Bécancour, measuring seven arpents by 20 arpents deep, with a house, barn and stable, a land concession in the seigneurie of Dutort and the land in St-Sulpice she had purchased just two years before. In November of the same year, another notarial document was drawn up in which Madeleine accepts a pension from her children to support her for the remainder of her life. She moved in with her daughter Françoise and her husband François Dufaux.

1724 burial record for Marie Madeleine Raclos (Ancestry)

Madeleine deteriorated rapidly. She no longer wanted to live with her daughter, nor go to the Ursuline hospital. Notary Poulin wrote in 1720 that she "had a very troubled mind and had become a child." Her children met again to decide what to do. Françoise was asked to continue caring for her mother and was given additional monies for her troubles. Françoise and her husband continued to care for Madeleine for an additional four years, during which "she plunged into a most complete state of dementia."

Marie Madeleine Raclos died at the age of 68. She was buried on July 8, 1724, in the parish cemetery of Trois-Rivières.

Legacy

Nicolas Perrot's many western adventures earned him a nickname among some indigenous people: "Metamiens", a word meaning "man with the iron legs," possibly referring to the fact that white explorers and traders introduced first nations to useful metallic objects.

Benjamin Sulte wrote that Nicolas Perrot "was one of four or five prominent figures of the 17th century to travel to the West." He is inextricably linked to Trois-Rivières, where most residents know of his legacy. He also added that "Before 1671, Perrot was just a coureur des bois trading on his own account, perhaps with a few associates, and without fanfare, but having acquired an extraordinary personal prestige in the minds of the Indigenous and regarded as a first-rate interpreter and orator. Evidently more educated than most men who led such wandering lives, gifted with superior talents, brave and cunning as possible, he dominated in both his French entourage and with the people who came into contact with him. Perrot had beautiful handwriting and a skill for describing what he saw during his many voyages".

Nicolas Perrot's signature

Many plaques and sites commemorate the life and travels of Nicolas Perrot. For a complete list, visit the Association of Descendants of Nicolas Perrot website.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/recherche?numero=243236), entry for Nicolas Perrault / Perrot (person #243236), updated on 20 Feb 2019.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/recherche?numero=016074), entry for Madeleine Raclot (person #016074), updated on 14 Sep 2017.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) online database (https://www.prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/3781), entry for Nicolas Perrault and Marie Madeleine Raclos, union #3781.

Jacques Saintonge, Nos Ancêtres volume 4 (Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, Éditions Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, 1983), 141-154

Peter Gagné, King’s Daughters & Founding Mothers: Les Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, Volume Two (Orange Park, Florida : Quintin Publications, 2001), 478.

Mona Andrée Rainville, "Les RACLOT de Chaumont en Bassigny à la Nouvelle-France," Academia.edu (https://www.academia.edu/30487254/Les_RACLOT_de_Chaumont_en_Bassigny_a_la_Nouvelle_France)

"Recensement du Canada, 1666", Library and Archives Canada (https://collectionscanada.gc.ca/), entry for Nicolas Pero, household of Marie Pournin, Montréal, page 118, 1666, Québec, Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667", Library and Archives Canada (https://collectionscanada.gc.ca/), entry for Nicolas Perrot, 1667, Montréal, page 174, Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau", Library and Archives Canada (https://collectionscanada.gc.ca/), entry for Nicolas Perrot, seigneurie de Lintot, 14 Nov 1681, Québec, Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (www.Archiv-Histo.com), " Société entre Nicolas Perrot, Jean Dupuis, Denis Masse, Pierre Poupart, Jean Guytard et Jacques Benoist," 2 Sep 1670, notary R. Becquet.

Parchemin, "Contrat de mariage entre Nicolas Perrot, fils de François Perrot et de Marie Sivot, de Davray, évêché d'Autun; et Madeleine Raclos, fille de Bon Raclot et de Marie Viennot," 11 Nov 1671, notary G. de Larue.

Parchemin, "Procuration de Nicolas Perrot, à Marie-Madeleine Raclos, son épouse, de la rivière Sainct Michel," 17 May 1685, notary A. Adhémar de Saint-Martin.

Parchemin, "Vente d'une terre située à St Sulpice; par Pierre Gour et Catherine Richome, son épouse, de St Sulpice, à Marie-Madeleine Raclaux, veuve de Nicolas Perot, capitaine, de la côte de Bécancour, absente, ce acceptant pour elle Pierre Perot, de St Sulpice, son fils," 18 Oct 1717, notary N. Senet dit Laliberté.

In collaboration with Claude Perrault, “PERROT, NICOLAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/perrot_nicolas_2E.html.

"Fonds Juridiction royale des Trois-Rivières - BAnQ Trois-Rivières," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/436217), "Requête de maître Jean le Chasseur (Lechasseur), conseiller du Roi, lieutenant-général de la Juridiction ordinaire des Trois-Rivières, comparant en personne, demandeur d’une part, à l’encontre de Nicolas Perot, (Perrault ou Perrot), demeurant aussi en cette ville, défendeur d’autre part. Après que le demandeur ait terminé sa requête, le défendeur a répondu qu’il n’a pas été mis en possession de la seigneurie de Rivière-du-Loup, (Louiseville) vendue par ledit Lechasseur. Lecture faite du contrat de vente passé devant Adhémar, notaire, 19 mai 1688, des titres et originaux passés devant Ameau, notaire, le 23 février 1690, il est ordonné que le défendeur soit condamné à payer au demandeur la somme de 1400 livres en castor, et les intérêts de la somme de 4000 livres aussi en castor, pendant les sept années où le défendeur a jouit de ladite seigneurie sans préjudice, la somme de 385 livres, 10 sols et 3 deniers pour les labours, et faute de paiement de 4000 livres, il est ordonné que la vente de la seigneurie soit déclarée nulle. Le demandeur peut entrer en possession de la seigneurie comme auparavant alors que le défendeur est condamné aux dépens.", 24 Nov 1698, reference TL3,S11,P2552, ID 436217.

"Collection Pièces judiciaires et notariales - BAnQ Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/387389), "Enquête par Jean Lechasseur, conseiller du Roi et lieutenant général de la Juridiction des Trois-Rivières, sur la séparation de biens demandée par Marguerite Raclos (Raclot) d'avec son mari Nicolas Perrot (Perrault)," 29 Aug 1702, reference TL5,D313, ID 387389.

"Fonds Juridiction royale des Trois-Rivières - BAnQ Trois-Rivières," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/436666), "Requête de Pierre Hazeur, sieur de Lherme (Delorme), prêtre curé de Champlain, demandeur, contre Madeleine Raclos, défenderesse, comparant par Nicolas Perrot (Perrault), son mari, pour que cette dernière accepte la somme de 3586 livres et 4 sols en monnaie de cartes en cours de ce pays qu’il lui doit selon un billet du 2 novembre 1713; le défendeur répond qu’il est prêt de recevoir le montant en espèce sonnante; il est ordonné que le défendeur recevra les 3586 livres et 4 sols en monnaie de cartes et que s’il refuse, elle sera consignée au greffe à ses risques et périls et il est condamné aux dépens taxé à 4 livres et 10 sols, monnaie de France," 26 Nov 1714, reference TL3,S11,P3001, ID 436666.

"Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968", Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/), burial of Nicolas Perrot, 14 Aug 1717, Bécancour.

"Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968", Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/), burial of Marie Magdelaine Perot, 8 Jul 1724, Trois-Rivières (Immaculée-Conception, cathédrale l'Assomption).

Thuot, Jean-René, "La pratique de l’inhumation dans l’église dans Lanaudière entre 1810 et 1860 : entre privilège, reconnaissance et concours de circonstances", 2006, Études d'histoire religieuse, 72, 75–96, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/1006589ar)