Charles Flagéole dit Latulippe & Marie Josèphe Henry

Explore the life of Charles Flagéole dit Latulippe, a French soldier who arrived in New France in the mid-1700s, and his wife Marie Josèphe Henry. Learn how this couple built a life along the Batiscan River during a time of war, land concessions, and political change in colonial Québec.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Charles Flagéole dit Latulippe & Marie Josèphe Henry

From Dole to Batiscan: A Soldier’s Journey to New France

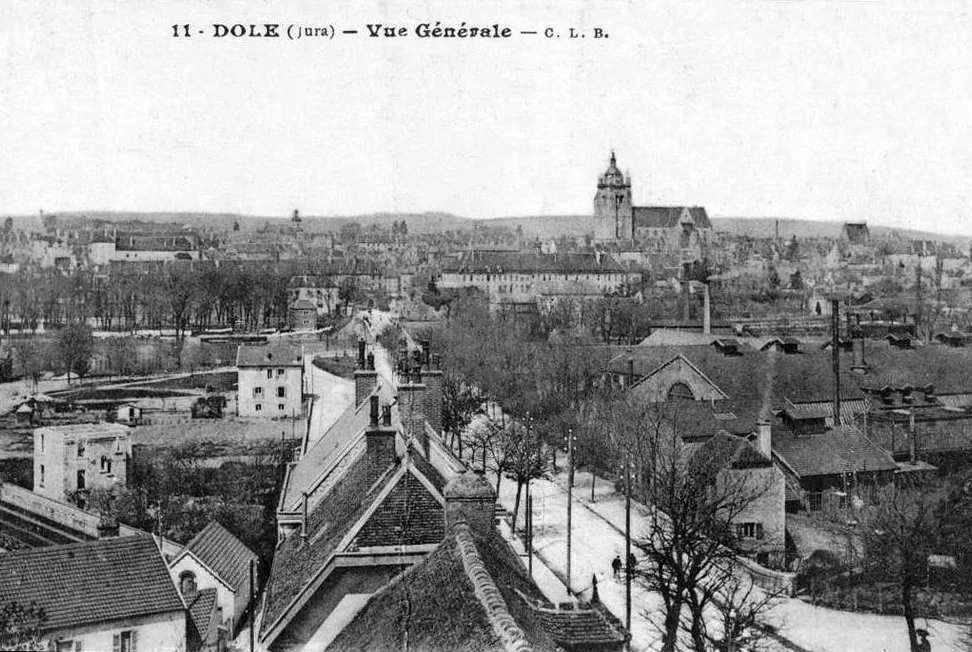

Charles Flagéole dit Latulippe, son of Claude Flagéole and Marie Denis, was born around 1727 in the parish of Notre-Dame in Dole, Franche-Comté (now in the Jura department).

In the mid-18th century, Dole was a relatively quiet market town surrounded by vineyards, forests, and farmland. Local life revolved around small-scale trades, seasonal labour, and subsistence farming, with only limited artisanal or industrial activity. Like much of rural France, Dole’s lower classes lived under the burdens of the seigneurial system, where peasants owed dues and services to landowners and were subject to a rigid social hierarchy. Life could be especially precarious for landless young men, who faced restricted access to trades (often governed by guilds), heavy taxation, and the lingering effects of poor harvests and food shortages that struck many parts of France in the early 1740s.

Location of Dole in France (Mapcarta)

Opportunities for advancement in Dole were scarce, and military service presented one of the few possible avenues for change. For young men like Charles, enlistment in the colonial troops may have offered a way out of poverty, the lure of travel and adventure, and—perhaps most importantly—a chance at land ownership and a better life in the colonies.

The 1740s were a time of widespread warfare in Europe, particularly with the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), which drew France into a costly and protracted conflict. As a result, military recruitment intensified across the kingdom. Among the forces looking for men were the Compagnies franches de la Marine, France’s colonial infantry units. Though technically under the authority of the navy, these soldiers served as land troops in overseas colonies such as Canada, Louisiana, and the Caribbean. The war increased the need for men to garrison forts, defend trade routes, and support local militias in New France, where tensions with British forces and Indigenous allies were escalating. Recruiters were dispatched to provincial regions like Franche-Comté, targeting smaller towns such as Dole where rural youth had few prospects and little to lose. Incentives such as enlistment bonuses, food, clothing, and paid transport to Atlantic ports like Rochefort or Brest made the offer appealing to many.

For a young man like Charles, the decision to enlist in the Compagnies franches de la Marine would have been shaped by a combination of necessity and opportunity. Military service promised steady income, regular meals, and relief from the obligations of corvée labour or militia drafts. More importantly, it offered a possible escape from the poverty and rigid social hierarchy of Old Regime France. The colonial troops were among the few institutions that provided a path to land ownership: after six or more years of service, soldiers could request discharge and receive land in New France. This opportunity—unthinkable for most young men in France—helped drive many to commit to military life abroad. For those willing to brave the Atlantic crossing and the dangers of frontier service, Canada offered the promise of a new start.

Postcard of Dole, circa 1905-1914 (Geneanet)

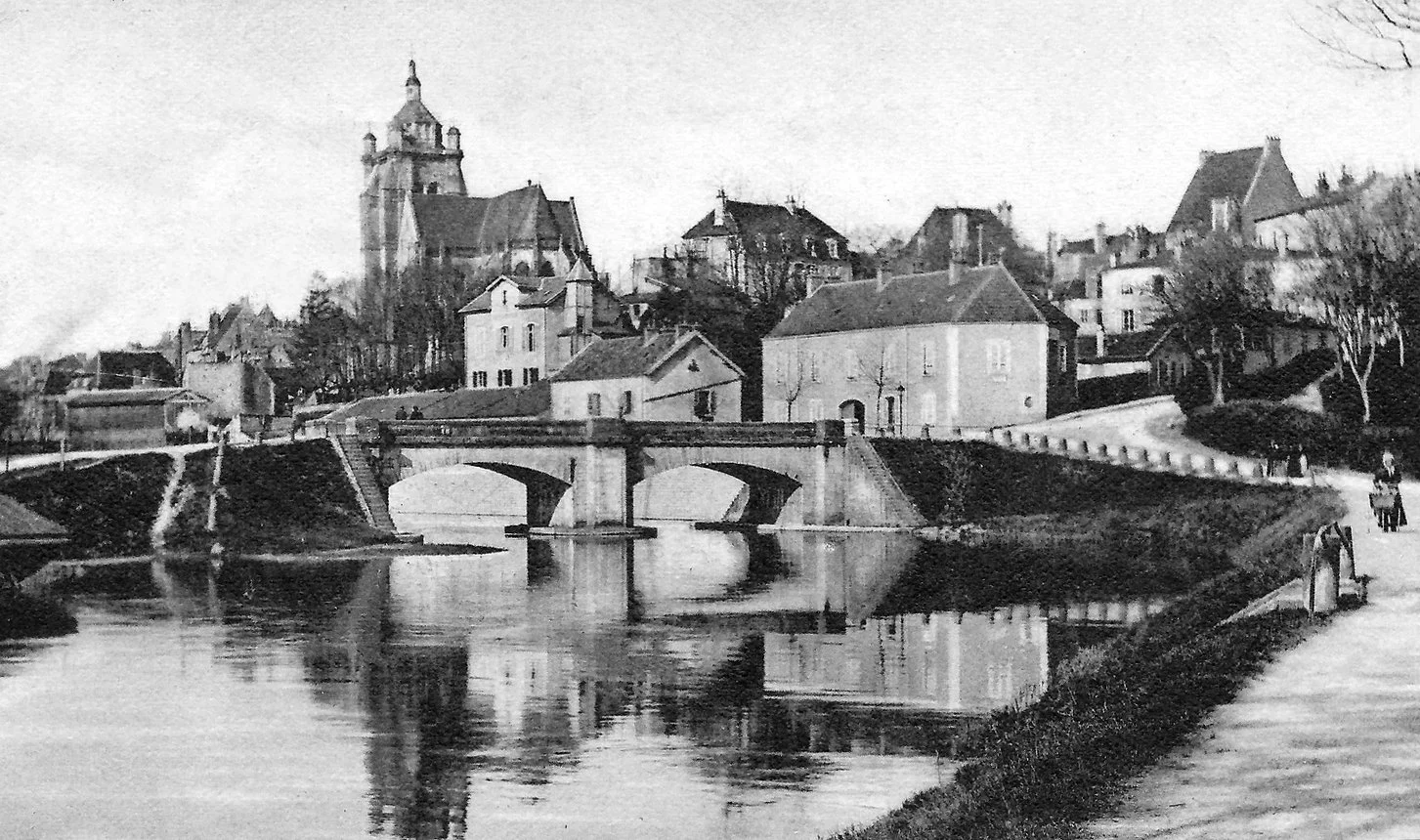

Postcard of Dole, circa 1907 (Geneanet)

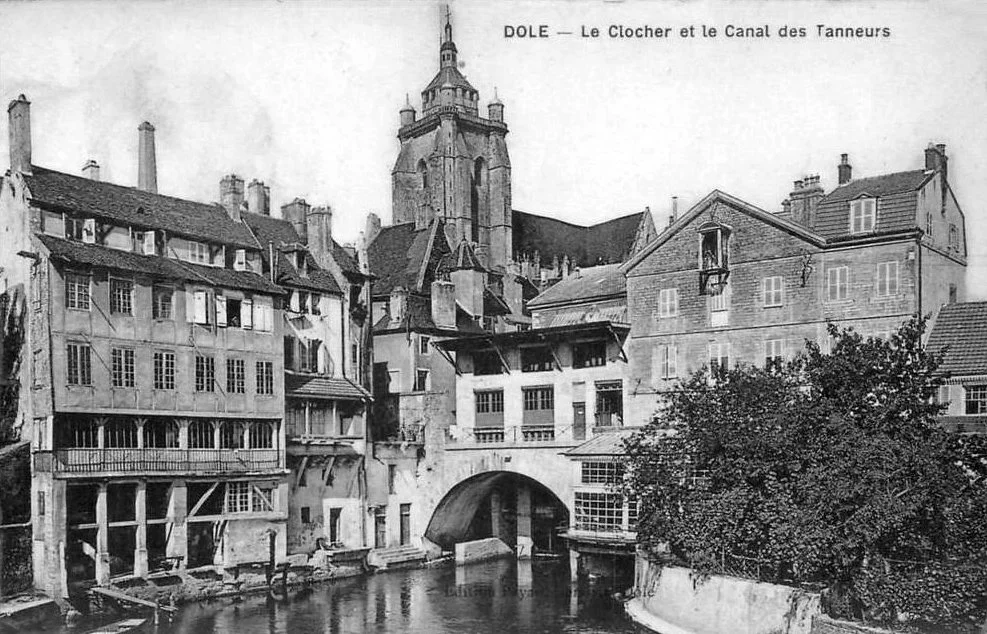

Postcard of Dole, circa 1910-1925 (Geneanet)

Postcard of Dole, circa 1952-1956 (Geneanet)

A Soldier in the Compagnies franches de la Marine

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (July 2025)

The exact date of Charles’s arrival in Canada is unknown. His dit name, however, implies that he was a soldier. A compiled list of soldiers places “Charles Flageole Latulippe” in Batiscan in 1758, in the company of Captain Basserode—one of the independent Marine companies active during the Seven Years’ War (known in North America as the French and Indian War, 1754–1760).

Serving in the Compagnies franches de la Marine meant that Charles was part of the principal French garrison force in Canada. These troops protected settlements like Québec and Montréal, manned frontier forts, and guarded fur trade routes. During the war, however, France also sent regular army regiments under General Montcalm to reinforce the colony. By 1760, New France had fallen to Britain. The fall of Montréal in September 1760 effectively ended French rule; the victorious British disbanded the Compagnies franches in Canada as part of the surrender terms. Many French soldiers were repatriated to Europe after the war. Charles Flagéole was an exception: instead of returning to France, he remained in Canada. It is possible he left military service during the chaotic final year of the war (perhaps deserting or being discharged when the companies disbanded) and chose to settle as a colonist. His dit name, Latulippe, thus became a permanent part of his identity in Canada.

Perhaps Charles met his future bride while guarding the outpost of Batiscan or Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan. As her father was also a soldier, he may have personally known Charles and offered his daughter’s hand in marriage.

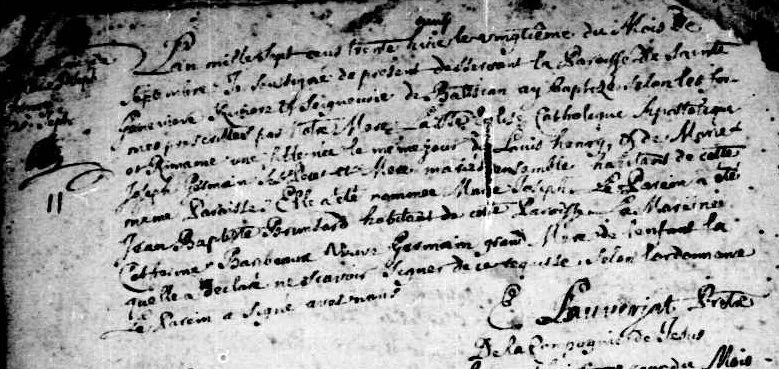

Marie Josèphe Henry, daughter of Louis Henry and Marie Josèphe Germain dite Magny, was born on September 20, 1739. She was baptized the same day in the parish of Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan, in Canada, New France (a French colony). Her godparents were Jean Baptiste Brunsard and Catherine Baribeaux, her grandmother. Only the godfather knew how to sign.

1739 Baptism of Marie Josèphe Henry (Généalogie Québec)

Marie Josèphe grew up in a relatively small family—she was the eldest of only two Henry children. She spent her childhood in Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan.

Louis Henry and Marie Josèphe Germain dite Magny

Louis Henry, the son of Marin and Jeanne Evesson (or Guerson), was born around 1707 in the parish of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. His father, Marin, a journeyman silversmith, lived with his wife on rue des Canettes in Paris. Louis was first mentioned in Canada in 1729 as a soldier in the Compagnies franches de la Marine. He married Marie Josèphe Germain dite Magny in Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan in 1735 and had two daughters before separating. Both Louis and Marie Josèphe met similarly tragic ends. Louis died in Berthierville in 1785; his burial record indicates he was an “elderly man found the previous day, drowned in the river while operating a rowboat.” Six years later, in December 1791, Marie Josèphe “was found frozen near Joseph Rousseau’s barn.” These events illustrate the very real dangers of the Canadian environment at the time.

Marriage and Family

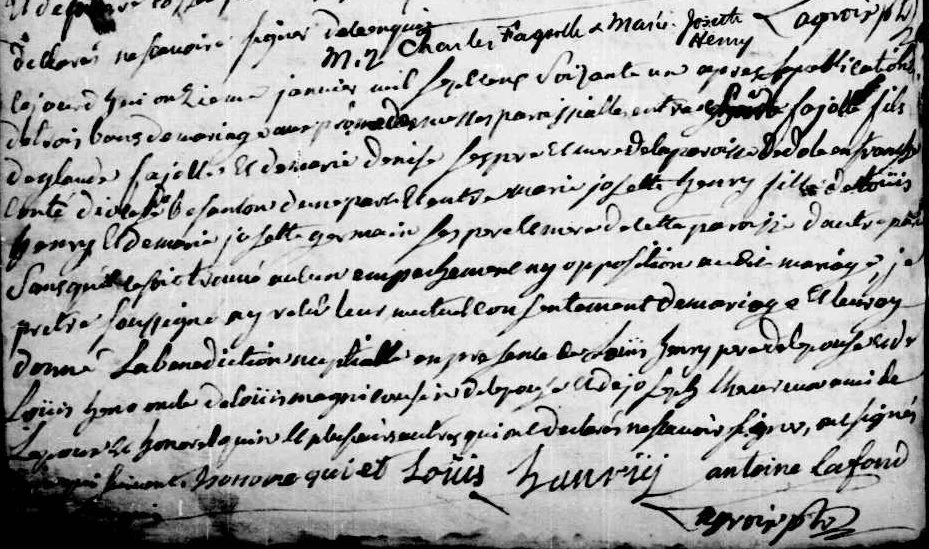

On January 5, 1761, royal notary Nicolas Duclos drafted a marriage contract between Charles “Flageol,” residing in Rivière Batiscan in the parish of Sainte-Geneviève, and Marie Josèphe Henry, also of Rivière Batiscan. Charles was about 34 years old, while Marie Josèphe was 21. The contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. Charles endowed his future wife with a customary dower of 600 livres. The préciput was set at 300 livres. The préciput, under the regime of community of property between spouses, was an advantage conferred on one of the spouses—generally the survivor—consisting of the right to levy, upon dissolution of the community, certain specified property or a sum of money. Neither the bride nor groom was able to sign the marriage contract.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children. After-death inventories were essential for listing all assets within the community to ensure proper division.

Charles and Marie Josèphe were married six days later, on January 11, 1761, in the parish of Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan. Their witnesses were Marie Josèphe’s father, her uncle Louis Heno (Hénault), and her cousin Louis Magny, as well as Charles’s friend Joseph Lheureux and Honoré Loquin. Neither the bride nor the groom was able to sign the marriage record, but Louis Henry, Marie Josèphe’s father, did sign his name.

1761 Marriage of Charles and Marie Josèphe (Généalogie Québec)

The couple settled in Batiscan and had at least nine children:

Charlotte (1762–1848)

Marie Louise (1764–?)

Charles (1766–1837)

Françoise (1768–1853)

Claude (1771–1851)

Marie (ca. 1773–1849)

François (1778–1838)

Nicolas (ca. 1779–1819)

Alexis (1783–1855)

Times of Political Change

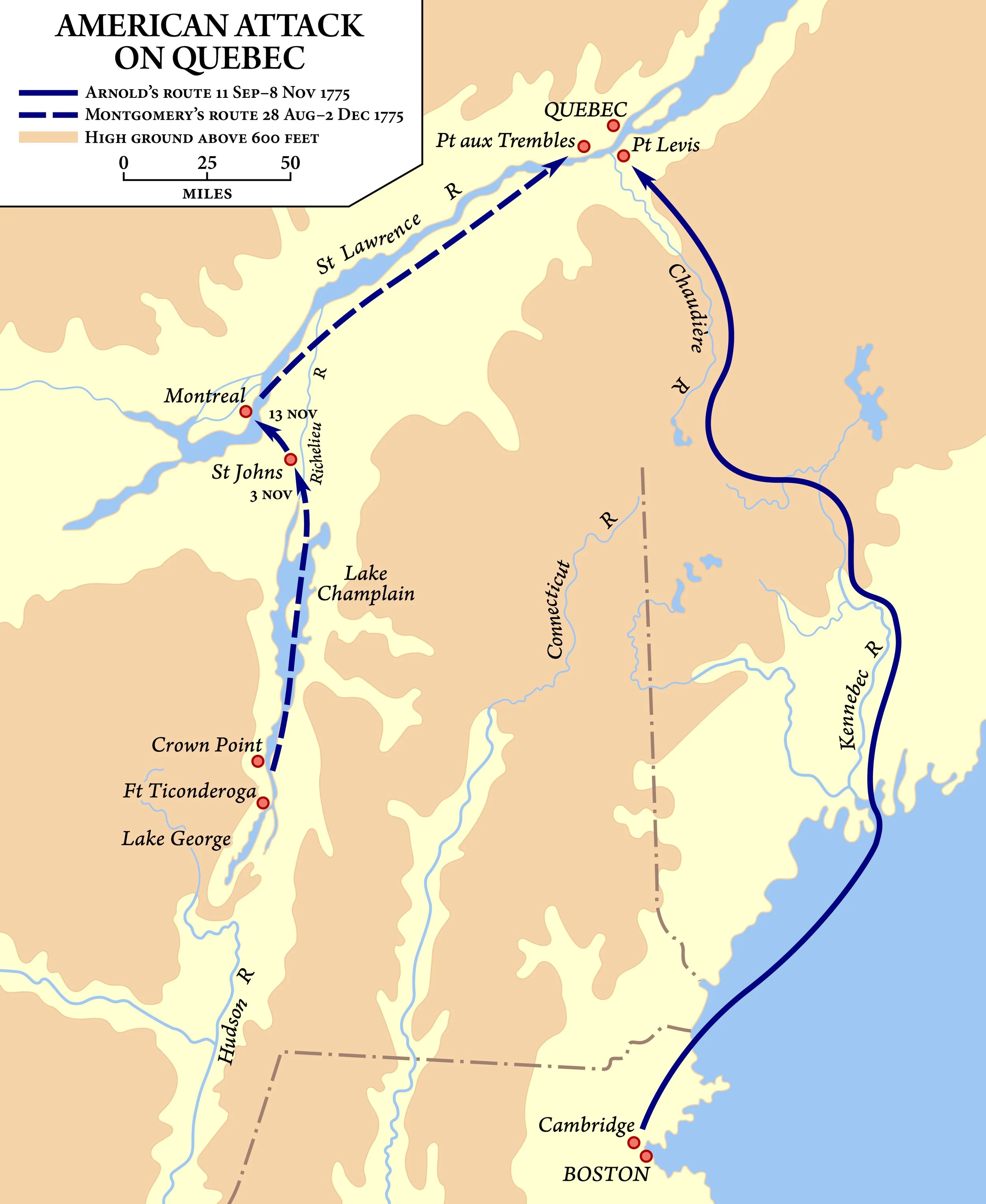

“American attack on Quebec: routes of the Arnold and Montgomery expeditions,” United States Army Center of Military History (Wikimedia Commons)

During the 1760s and 1770s, Charles and Marie Josèphe would have witnessed the early adjustments to British rule. The Quebec Act of 1774 was particularly significant: it officially allowed French civil law to continue and recognized the rights of the Catholic Church. This meant they could continue to practise their Catholic faith and were not forced to assimilate into the English language or Protestant religion.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out, the inhabitants of Quebec were courted by American rebels, but residents of Batiscan largely remained neutral or loyal to the Crown. In late 1775, an American invasion force passed through the St. Lawrence Valley toward Quebec City. There was a brief occupation of nearby Trois-Rivières by American troops in the spring of 1776, which was repelled by the British. It is possible that Charles—by then about 49 years old—was mustered into the local militia to help resist the incursion, as most able-bodied men up to age 60 were enrolled. The Battle of Trois-Rivières in June 1776 saw the defeat of the American invaders not far from Batiscan. Ultimately, the American threat subsided, and Quebec (including Batiscan) remained under British control. For Charles and Marie Josèphe’s family, these events likely sparked discussion at church on Sundays but did not significantly disrupt their daily lives.

Land at Batiscan

On January 17, 1768, Marie Josèphe Germain dite Magny, legally separated from her husband (séparée de corps et de biens) Louis Henry, sold her inheritance rights to real estate located on the grande côte de Batiscan to her daughter Marie Josèphe and son-in-law Charles, for the sum of 18 livres.

Séparée de corps et de biens

The phrase séparée de corps et de biens de son mari indicates that a woman was legally separated from her husband in both physical and financial terms. A séparation de corps released the couple from the obligation to live together, while a séparation de biens allowed the woman to manage her own property and income independently—an important distinction under the régime de la communauté de biens (community property regime), which ordinarily gave the husband control over marital assets. This type of legal separation was granted by a civil or ecclesiastical court, usually in cases of abandonment, mistreatment, or serious marital conflict. Although divorce was not permitted in New France due to its Catholic legal framework, legal separation was recognized and enforceable.

A year later, on January 21, 1769, Charles and Marie Josèphe sold their claims to the land on the grande côte de Batiscan to Nicolas Quessy for 120 livres.

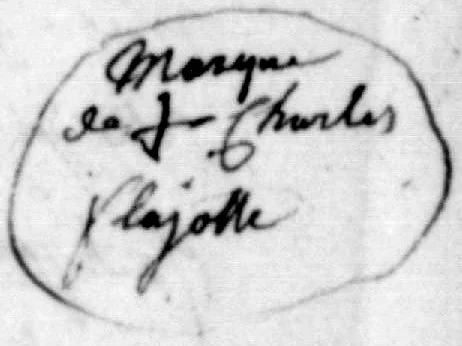

Charles’s mark on the 1788 deed of sale

On October 31, 1788, Charles purchased land adjoining his own, located at the Rivière Batiscan, from Augustin Maton for 90 livres. The land measured three-quarters of an arpent of frontage, facing the river, by twenty-one arpents in depth. Charles agreed to pay the seigneurial cens and rentes going forward. As he could not sign, he left his mark on the deed of sale.

Charles increased his holdings even more the following year. On April 2, 1789, he received “continuation” of a land concession at the Rivière Batiscan from the Compagnie de Jésus (the Jesuits). The land measured three-quarters of an arpent of frontage by twenty arpents deep. Charles agreed to pay the Jesuit seigneurs one sol for the area, plus one sol per arpent of frontage in cens, starting on the next feast day of Saint-Martin. He also promised to have his grain ground at the seigneurial mill and to maintain the roads passing through the land.

1721 map of the seigneurie of Batiscan (1788 copy by J. McCarthy based on the original by de Lanaudière, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Last Will and Testament

On February 7, 1806, 66-year-old Marie Josèphe dictated her testament to notary Augustin Trudel:

Before the undersigned notary public in the Province of Lower Canada residing in Sainte-Anne, and the undersigned witnesses named at the end, was present Marie Josephe Henry, wife of Mr. Charles Flageole, residing in the parish of Saint-Stanislas at Rivière Batiscan, being sound of body, mind, memory, understanding, and judgment, as appeared to the said undersigned notary and witnesses by her words, speeches, gestures and statements, who, considering that all nature is subject to death, that in this world there is nothing so uncertain as the hour of death, and not wishing to be overtaken by it before having put her spiritual and temporal affairs in order, by disposing of the little property that God has been pleased to bestow upon her—as is permitted by the laws currently in force in this province—she has made, dictated and named to the undersigned notary, the said witnesses present, her present last will and testament as follows.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (July 2025)

Firstly, as a good Roman Catholic Christian, in which religion she wishes to live and die, she commends her soul to God the Creator of the universe, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, begging His divine mercy through the merits of the Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ and through the intercession of the glorious Virgin Mary and all the saints of the heavenly court, to have mercy on her, forgive her sins, and place her in the Kingdom of heaven among the blessed.

Secondly, it is the will and instruction of the said Marie Josèphe Henry, testatrix, that before anything else, her debts be paid and any wrongs committed by her be made good by her executor, hereinafter named.

Thirdly, she wishes and instructs that her body, after death, be buried in the cemetery of the parish where she dies, and that five requiem masses be said in the year of her death for the repose of her soul.

Fourthly, and as for the rest and surplus of all her property–both movable and her own immovable acquests and conquests—which will belong to her on the day of her death in whatever place they may be situated and of whatever value and nature they may be, without exception or reservation, the said testatrix gives, bequeaths and leaves them in full ownership by her present will to Mr. Alexis Flageole, her son, living with her in the said parish of Saint-Stanislas, to show him the good friendship she has always had for him, to reward him for the good services he has always rendered her and which he still renders her daily, and so that he may remember her in his prayers. The said Mr. Alexis Flageole, the said testatrix makes and institutes as her universal legatee to enjoy and dispose of all the said property in full ownership from the day of her death and in perpetuity as his own and loyal acquest by virtue of the present will.

To execute and fulfil the present will, the said testatrix appoints and elects as her executor the said Mr. Alexis Flageole, her son and sole legatee, whom she asks to take the trouble to render her this last friendly service, into whose hands she relinquishes all her property in accordance with custom. She revokes all other wills and codicils that she may have made prior to this one, which alone she accepts as her last will and testament.

This was thus done, dictated and named by the said testatrix to the undersigned notary and the said witnesses, at Saint-Stanislas in the house and residence of Mr. Pierre Trépagnez in the year one thousand eight hundred and six, on the afternoon of the seventh of February, in the presence of the said Mr. Pierre Trépagnez and Mr. Antoine Trottier, farmers residing at the said place, witnesses for this called, who signed with us, the aforementioned notary, both at the end and at the bottom of each page of the present will. After the present will was read and reread by the notary in the presence of the aforementioned witnesses and the testatrix, she declared that she had heard and understood it well and persisted in it as her last will and testament, declaring that she could neither write nor sign. Reading done and redone.

Deaths of Charles and Marie Josèphe

At some point between the testament of Marie Josèphe in 1806 and 1810, she and Charles moved about 45 kilometres southwest to Saint-Antoine-de-la-Rivière-du-Loup (present-day Louiseville). Their son Nicolas had settled there, likely the reason for their move in their later years.

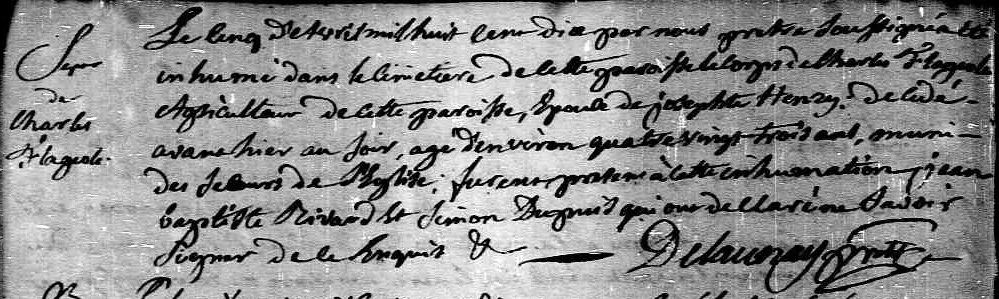

Charles Flagéole dit Latulippe died at the age of 83 on April 3, 1810. He was buried two days later in the parish cemetery of Saint-Antoine-de-la-Rivière-du-Loup, Lower Canada (then a British colony). The burial record indicates that he was an agriculteur (farmer) of the parish.

1810 Burial of Charles Flagéole (Généalogie Québec)

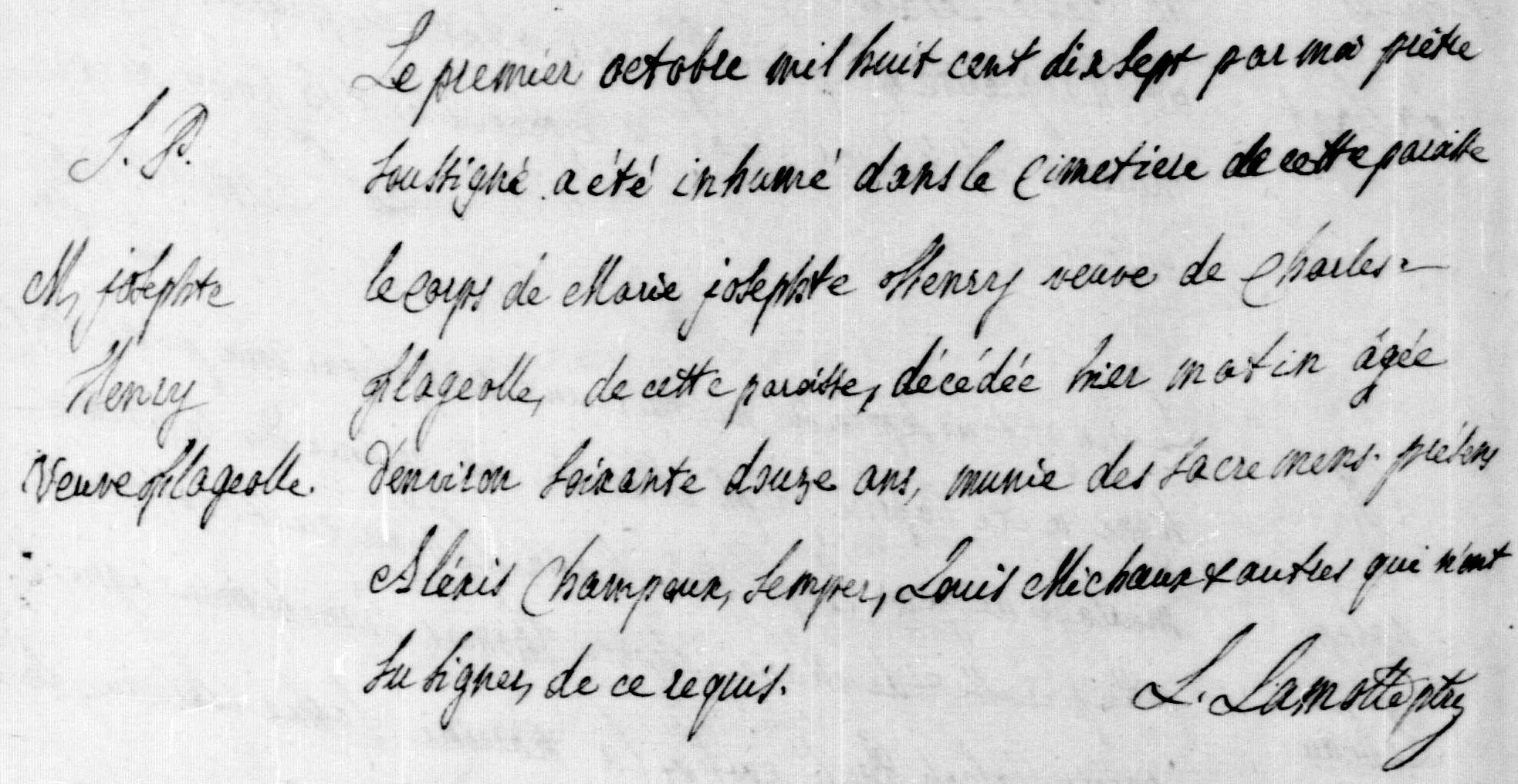

Marie Josèphe Henry died at the age of 78 on September 30, 1817. She was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Cuthbert, Lower Canada. [The burial record erroneously states that she was “about 72 years old.”] She was possibly living with her son Claude and his family, who were residents of Saint-Cuthbert at the time.

1817 Burial of Marie Josèphe Henry (Généalogie Québec)

From Soldier to Settler: A Life Built on the Batiscan

Charles Flagéole dit Latulippe and Marie Josèphe Henry lived through a pivotal period in the history of New France and early British Québec. From Charles’s arrival as a French colonial soldier to the couple’s years in Batiscan and Saint-Stanislas, their lives were shaped by war, shifting political regimes, and the demands of rural settlement. Through marriage, land acquisition, and family ties, they established themselves in a changing colony that was moving from French to British rule. Their story offers a glimpse into the everyday resilience and adaptability required to build a life in 18th-century Canada.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Charles Flageole Latulippe," Implantation des troupes de Terre (https://www.implantation-troupes-de-terre.historiamati.ca/ : accessed 4 Jul 2025), 1758, Basserode Compagny.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/110128 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), baptism of Marie Josephe Henry, 20 Sep 1739, Ste-Geneviève-de-Batiscan (Ste-Geneviève) ; citing original data : Drouin Collection, Institut généalogique Drouin.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/269818 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), marriage of Charles Fajolle and Marie Josephe Henry, 11 Jan 1761, Ste-Geneviève-de-Batiscan (Ste-Geneviève).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/2573933 : accessed 7 Jul 2025), burial of Charles Flageole, 5 Apr 1810, Louiseville (St-Antoine-de-la-Rivière-du-Loup).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/2911526 : accessed 7 Jul 2025), burial of Marie Josephte Henry, 1 Oct 1817, St-Cuthbert (Berthier).

"Actes de notaire, 1687-1769 // Nicolas Duclos," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3V7-1967-M?cat=538069&i=424&lang=en : accessed 3 Jul 2025), marriage contract of Charles Flageol and Marie Josephe Henry, 5 Jan 1691, images 425-427 of 2,594 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3V7-R9C9-Q?cat=538069&i=490&lang=en : accessed 3 Jul 2025), sale from Marie Joseph Germain dit Magnie to Charle Flageol and Marie Josephe Henry, 17 Jan 1768, images 491-493 of 2,856 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3V7-R98H-L?cat=538069&i=1265&lang=en : accessed 3 Jul 2025), sale of claims to land by Charles Flageol and Marie-Josèphe Henry to Nicolas Quesy, 21 Jan 1769, images 1,266-1,268 of 2,856.

"Actes de notaire, 1771-1793 // Charles Levrard," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3774001?docref=lBj1uqtJxlwLY3zF2jnZxg%3D%3D : accessed 3 Jul 2025), sale by Augustin Maton to Charles Flagéole, 31 Oct 1788, images 904-905 of 2,432.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3774001?docref=rzd-30ecsMstxrwGoMTqAA%3D%3D : accessed 3 Jul 2025), land concession to Charles Flagéole, 2 Apr 1789, images 1,065-1,066 of 2,432.

"Actes de notaire, 1799-1846 // J. Augustin Trudel," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4069447?docref=XwuRPqr1vHSBdwYu6Aw4lQ%3D%3D : accessed 7 Jul 2025), testament of Marie Josephe Henry, 7 Feb 1806, images 2,298-2,300 of 2,732.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/90209 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Louis HENRY, person 90209.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/90210 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Marie Josephe GERMAIN MAGNY, person 90210.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/37398 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Charles FLAGEOLE LATULIPPE LATURLIP and Marie Josephe HENRY, union 37398.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/recherche?numero=015040 : accessed 3 Jul 2025), entry for Louis HENRY (person 015040).