Robert Vaillancourt & Marie Gobeil

Discover the story of Robert Vaillancourt and Marie Gobeil, 17th-century pioneers of Île-d’Orléans and founders of the Vaillancourt family in Québec, Canada, and the United States. Explore their journey from Normandy and Poitou to New France and trace the origins of a lasting North American lineage.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Robert Vaillancourt & Marie Gobeil

Founders of the Vaillancourt Family in North America

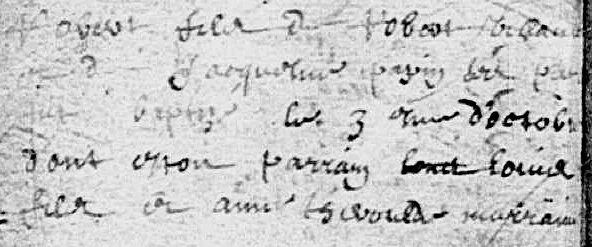

Robert Vaillancourt, son of Robert Vaillancourt and Jacqueline Papin, was baptized on October 3, 1644, in Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont, Normandy, France. His godparents were his brother Louis and [Marie?] Théraude. He had two other known siblings, also baptized in Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont: Magdelènne and François.

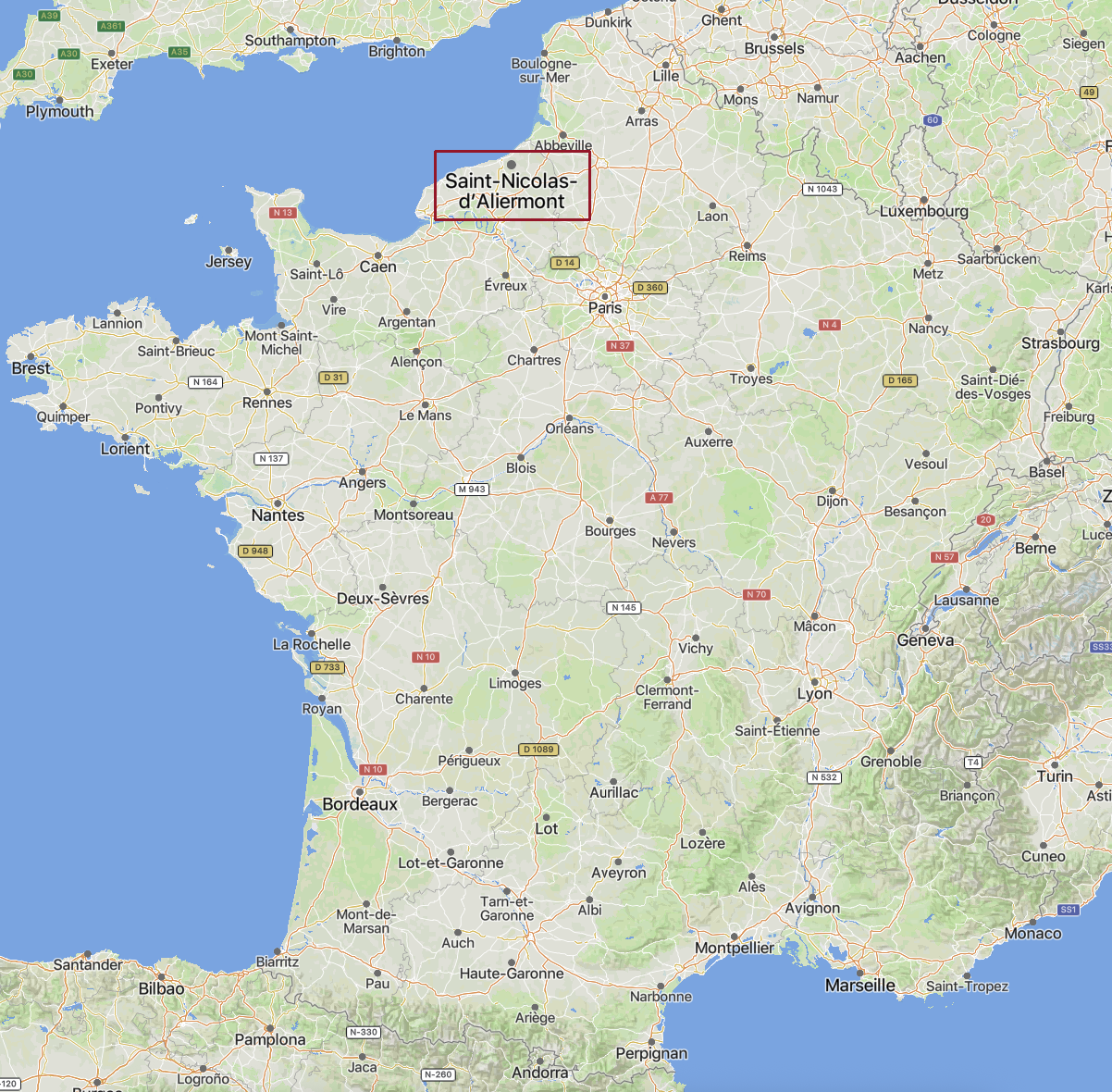

Located about 50 kilometres north of Rouen in the department of Seine-Maritime, present-day Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont is considered a bourg rural (rural village) with a population of about 3,700 residents, known as Nicolaisiens.

1644 baptism of Robert Vaillancourt (Archives de la Seine-Maritime)

Location of Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont in France (Mapcarta)

Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont: A Legacy of Craftsmanship

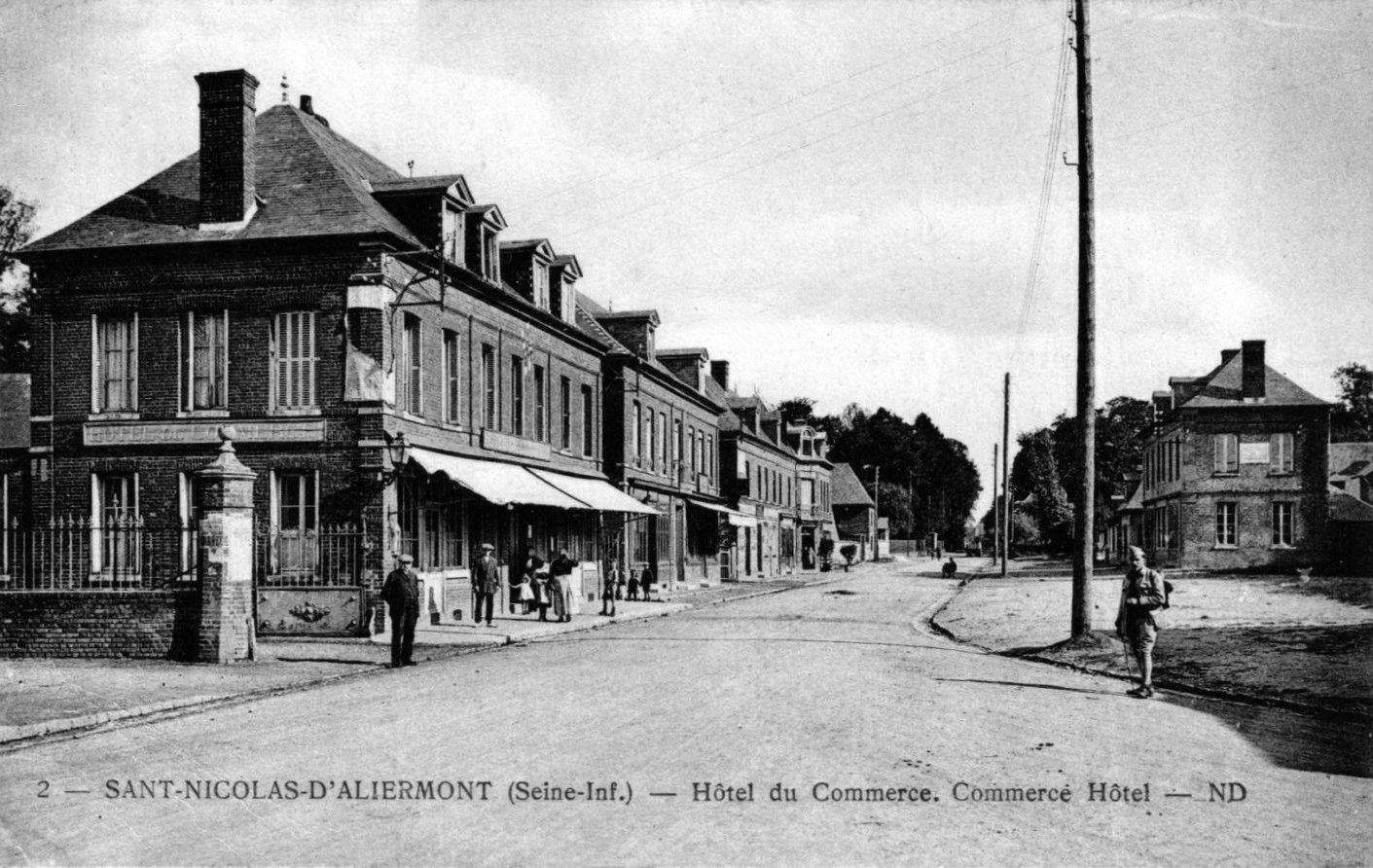

Robert’s hometown, Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont, has long been recognized for its skilled craftsmanship. During the 16th to 19th centuries, it evolved from a modest rural settlement into a centre of specialized trades. Its geographic position near Dieppe and access to raw materials helped it develop a strong artisanal economy. It was in 17th-century Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont that Robert learned the trade of chaudronnier (coppersmith).

By the 18th century, Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont had gained particular renown for its clockmaking industry. The craft was introduced in the late 17th century and flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries, with numerous workshops producing timepieces and components for domestic and export markets. This brought with it a concentration of related metalworking trades, including blacksmiths, tinsmiths (ferblantiers), and chaudronniers—coppersmiths or boilermakers—who fashioned copper and tin vessels and often supplied tools and parts for the horology trade.

Postcard of Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont, circa 1905-1914 (Geneanet)

Postcard of Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont, circa 1905-1914 (Geneanet)

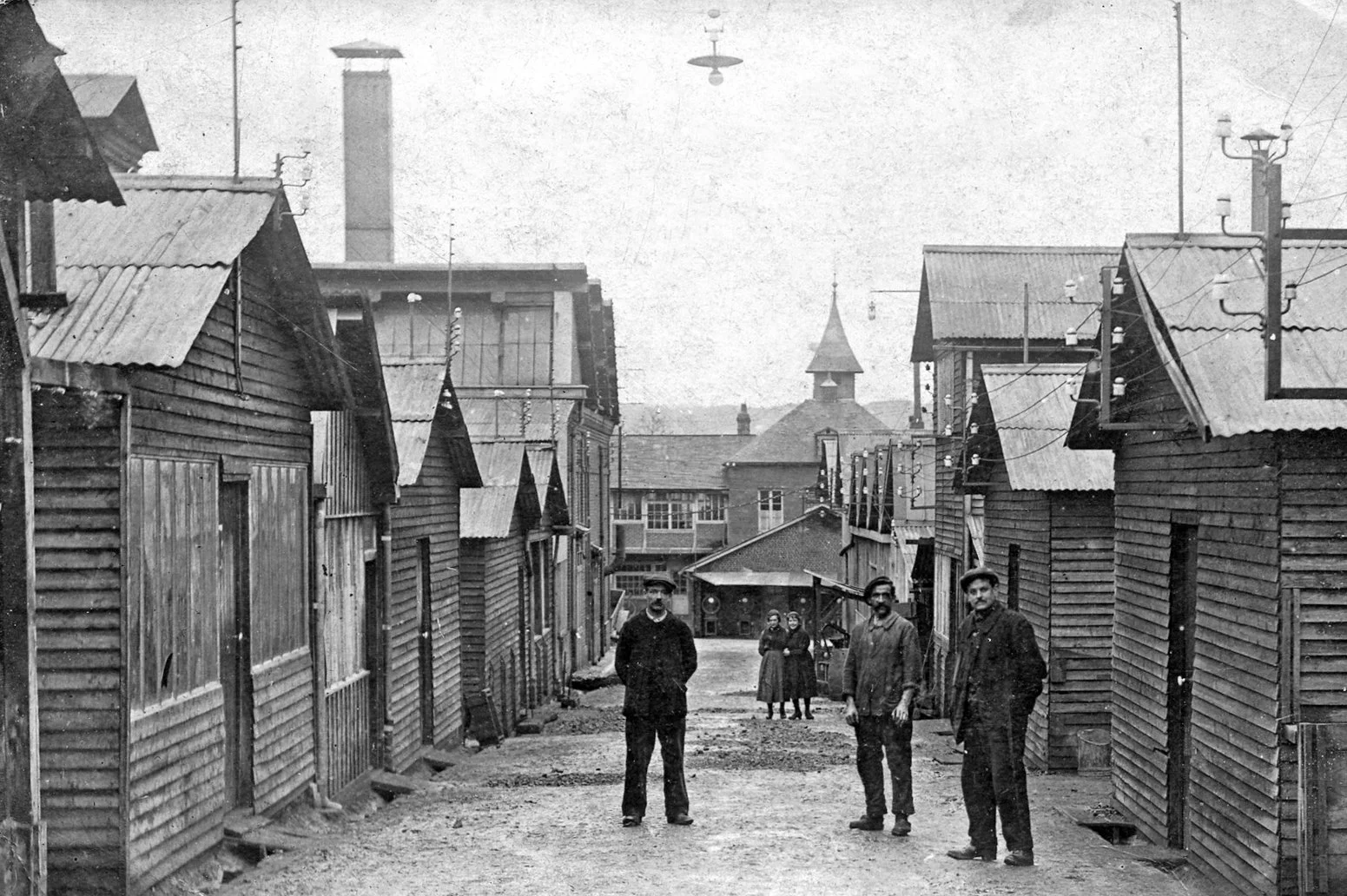

While the once-thriving network of independent workshops and clockmakers declined significantly in the 20th century—due in part to industrialization, global competition, and changing technologies—the legacy of the trade is preserved locally. Today, the Musée de l’Horlogerie (Clockmaking Museum), housed in a former factory, showcases the town’s historic role in precision timekeeping and the evolution of local craftsmanship.

Les Ateliers Vaucanson workshop, circa 1930 (Geneanet)

A Coppersmith in New France

Although the exact date of his arrival is unknown, Robert likely disembarked at the port of Québec in 1665. Most newcomers from France signed three-year work contracts before making the ocean crossing. Once their indenture ended, they were free to marry. Given Robert’s marriage in 1668, 1665 is the most plausible year of arrival.

The coppersmith (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, July 2025)

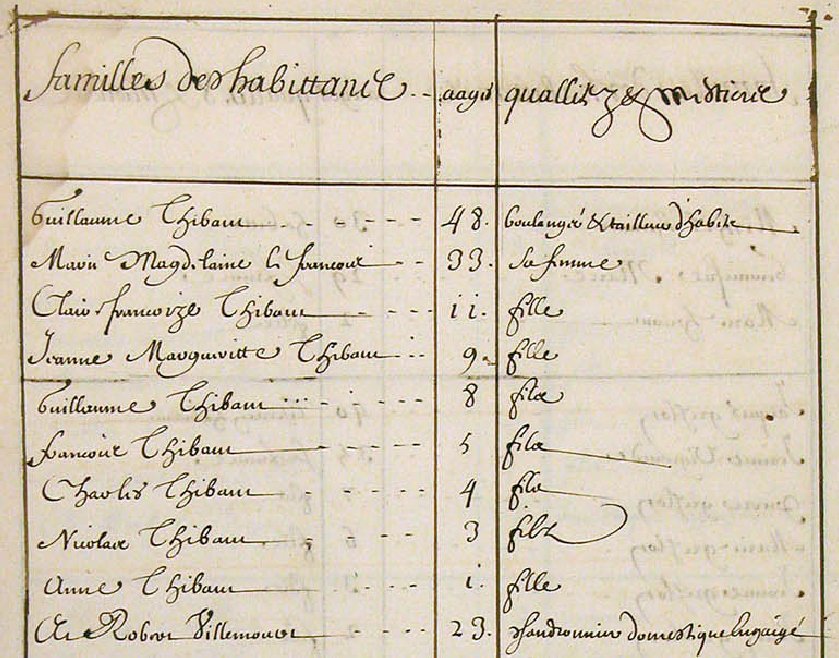

In the 1666 census of New France, Robert—listed as “Villemonet”—was recorded as a 23-year-old coppersmith and domestic servant, living on the côte de Beaupré with the family of Guillaume Thibault, a baker and tailor.

1666 census of New France for the Thibault household (Library and Archives Canada)

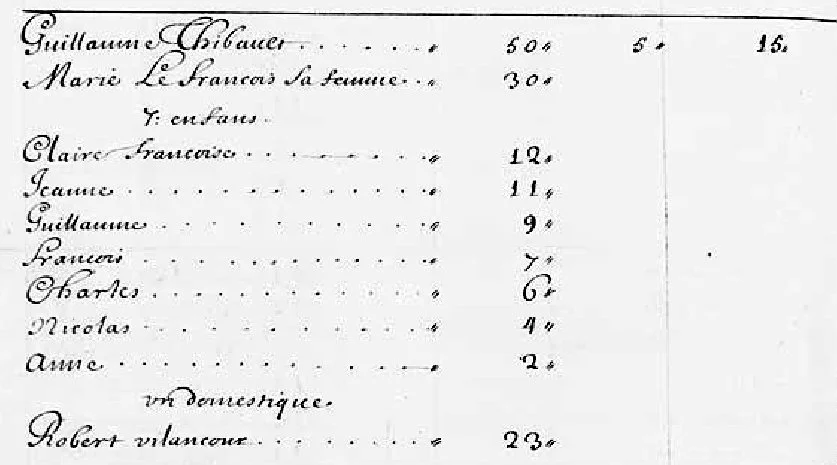

The following year, he was still in Thibault’s employ. In the 1667 census, Robert “Vilancour,” aged 23, was again listed as a domestic servant. The Thibault household owned five head of cattle and fifteen arpents of land cleared and under cultivation.

1667 census of New France for the Thibault household (Library and Archives Canada)

On August 3, 1668, with his indenture complete, Robert leased a farm and smallholding in Saint-François (now the Saint-Sauveur neighbourhood of Québec City). The property had been transferred to him by Gervais Bisson and Marie Boutet and was owned by the widow Anne Gasnier and the heirs of the late Jean Bourdon, seigneur of Saint-François and Saint-Jean. In exchange, Robert paid Bisson fifteen minots of wheat and two minots of peas and assumed the lease payments. [A minot was a dry measure equivalent to half a mine; one mine equalled about 78.73 litres.]

In Canada, Robert’s surname has been spelled in a variety of phonetic ways: Villencourt, Veyllancour, Veillancour, Veillancourt, Vaillancours, and Vaillancour.

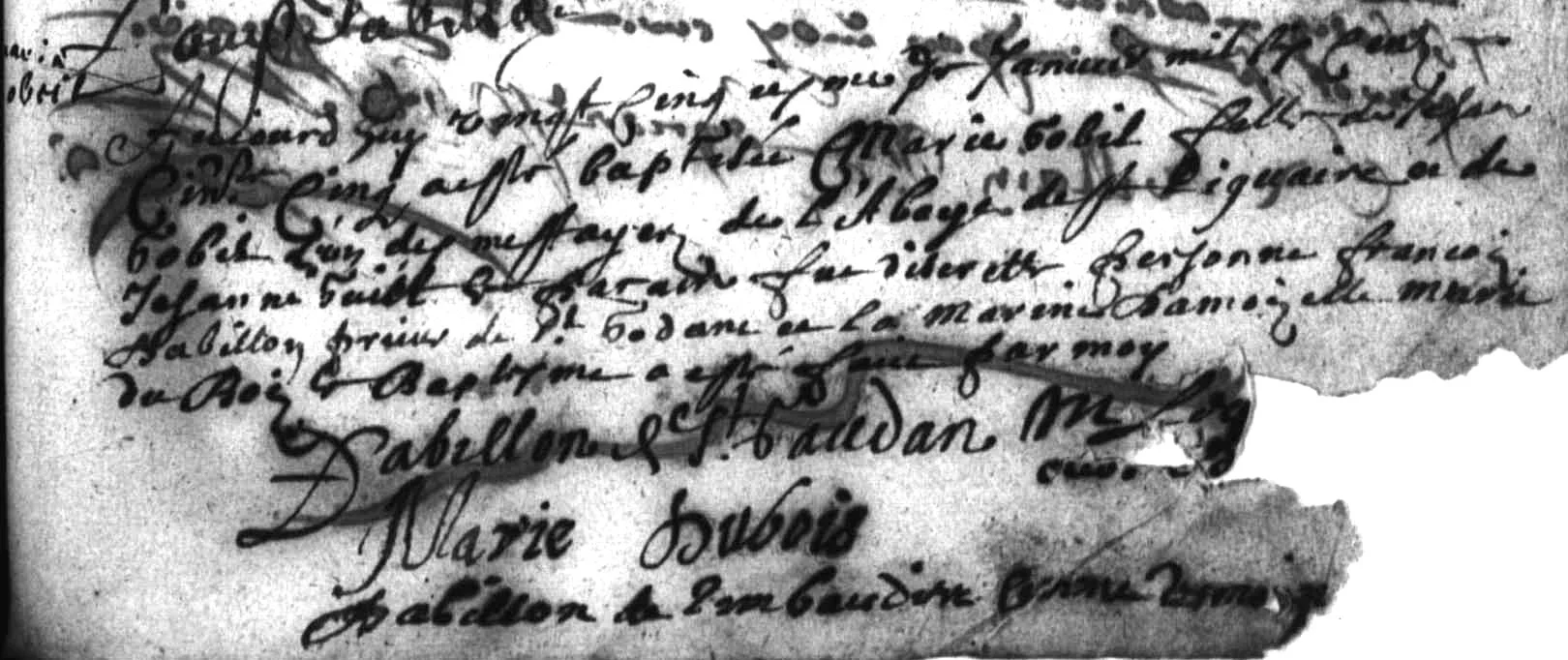

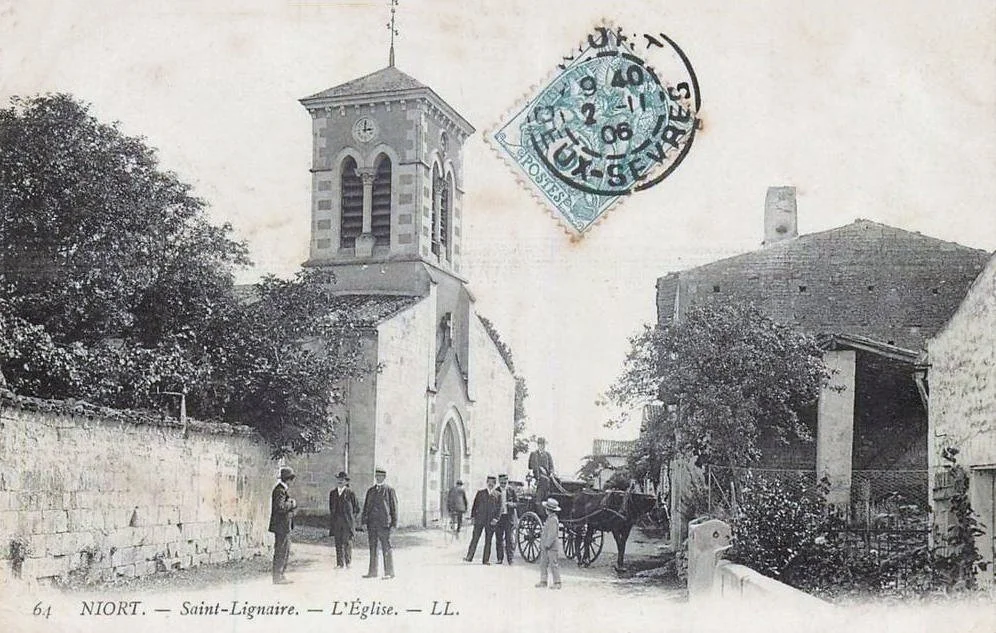

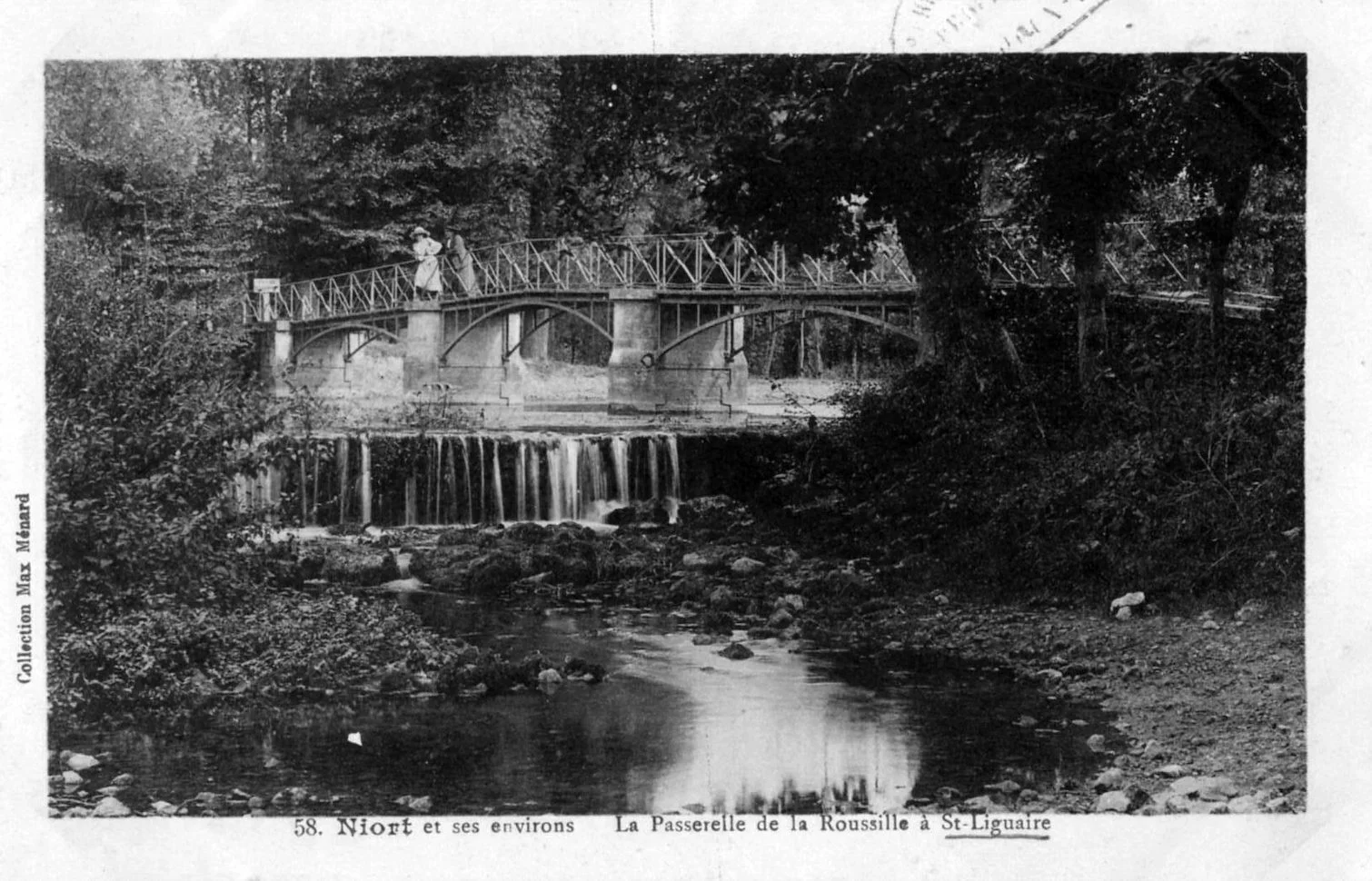

Marie Gobeil, daughter of Jean Gobeil and Jeanne Guillet, was baptized on January 25, 1655, at the parish of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine in Saint-Liguaire, Poitou, France. Her godparents were [François Dabillon?] and Marie Dubois. Today, Saint-Liguaire is part of the city of Niort, in the department of Deux-Sèvres.

1655 baptism of Marie Gobeil (Archives départementales des Deux-Sèvres)

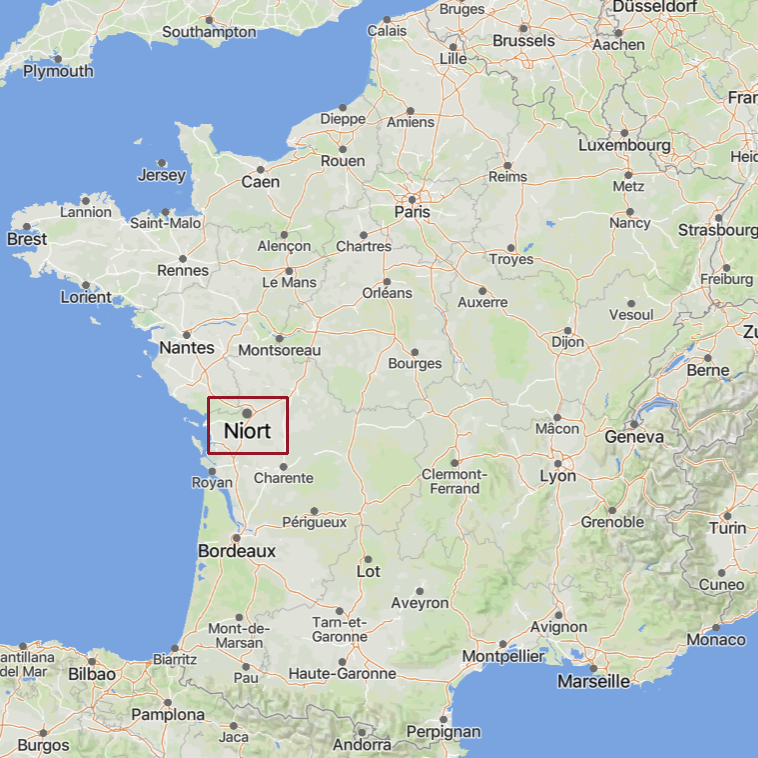

Location of Niort in France (Mapcarta)

Marie’s parents signed their marriage contract on April 14, 1654, in Saint-Liguaire. Her paternal grandparents were Pierre Gobeil, son of Michel Gobeil and Vincente Benoist, and Catherine Chaignaud, daughter of Guillaume Chaignaud and Jeanne Andrée, married on February 18, 1623, in Saint-Liguaire. Her maternal grandparents were Pierre Guiet, son of Paul Guiet and Marie Dourion, and Gabrielle Roquier, daughter of Guillaume Roquier and Françoise Desmier, married in Échiré (parish of Notre-Dame) on January 21, 1632.

Marie had three sisters baptized in Saint-Liguaire: Françoise, Marie, and Marie Jeanne Angélique. Four more siblings were born in Canada: Catherine, Barthélemy, Marie Marguerite, and Laurent.

Postcard of Saint-Liguaire, circa 1903-1906 (Geneanet)

Postcard of Saint-Liguaire, circa 1910-1913 (Geneanet)

The Gobeils Take Root in New France

The Gobeil family arrived in New France around 1665, likely in the same year as Robert Vaillancourt. They settled on the côte de Beaupré, in what would later become the parish of Château-Richer.

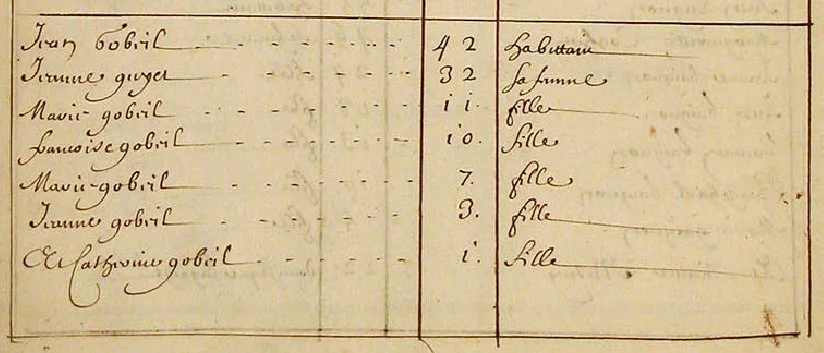

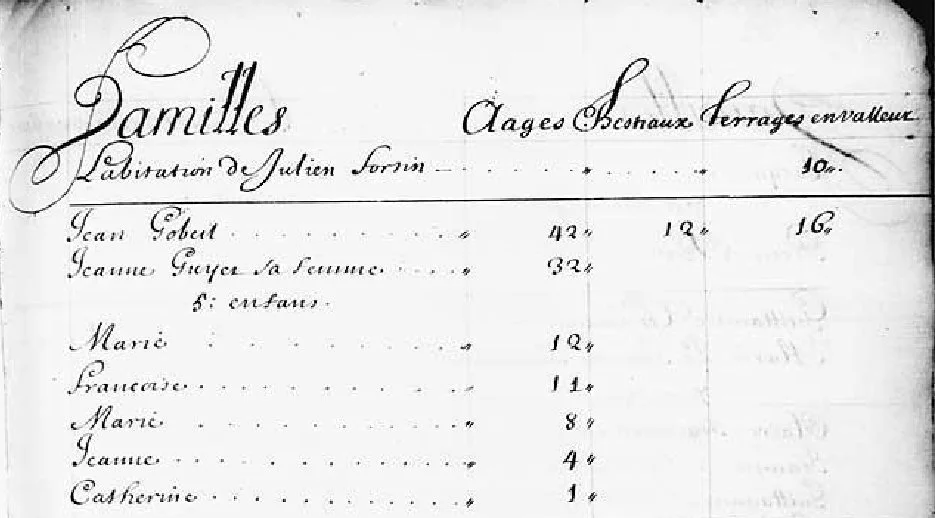

In the 1666 census, Jean Gobeil and Jeanne Guillet were recorded with their daughter Marie and four other daughters, residing on the côte de Beaupré. Jean was listed as an habitant.

1666 census of New France for the Gobeil family (Library and Archives Canada)

Canada’s First Census

Canada’s first census was conducted in 1666 under the direction of Jean Talon, the colony’s intendant. Although Talon had arrived in New France only the previous year and had no prior experience conducting a census, he pressed ahead with the task—despite France itself never having conducted one.

Talon organized a team of census takers armed with quill pens, ink, and paper. They travelled from household to household across villages and rural settlements, recording each resident’s name, age, occupation, and relationship to the head of the household.

The census took place during one of the harshest winters in 30 years. Despite the extreme cold and snow, the weather proved advantageous: most residents remained at home, making them easier to count. Over the course of several months, Talon’s team successfully enumerated 3,418 colonists in New France.

In the 1667 census, the Gobeil family was still residing on the côte de Beaupré. That year, they owned twelve head of cattle and sixteen arpents of cleared land.

1667 census of New France for the Gobeil family (Library and Archives Canada)

Marriage of Robert and Marie

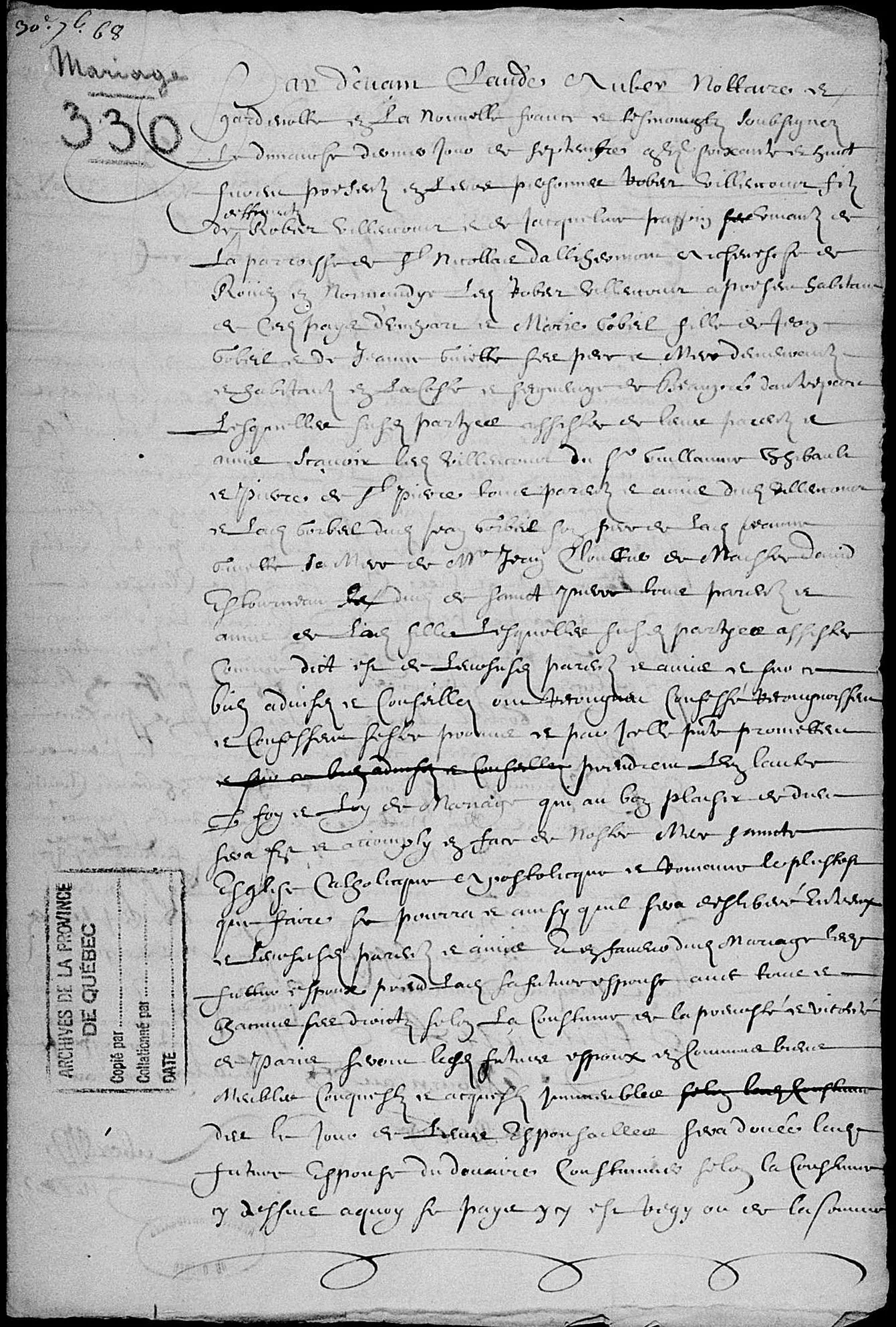

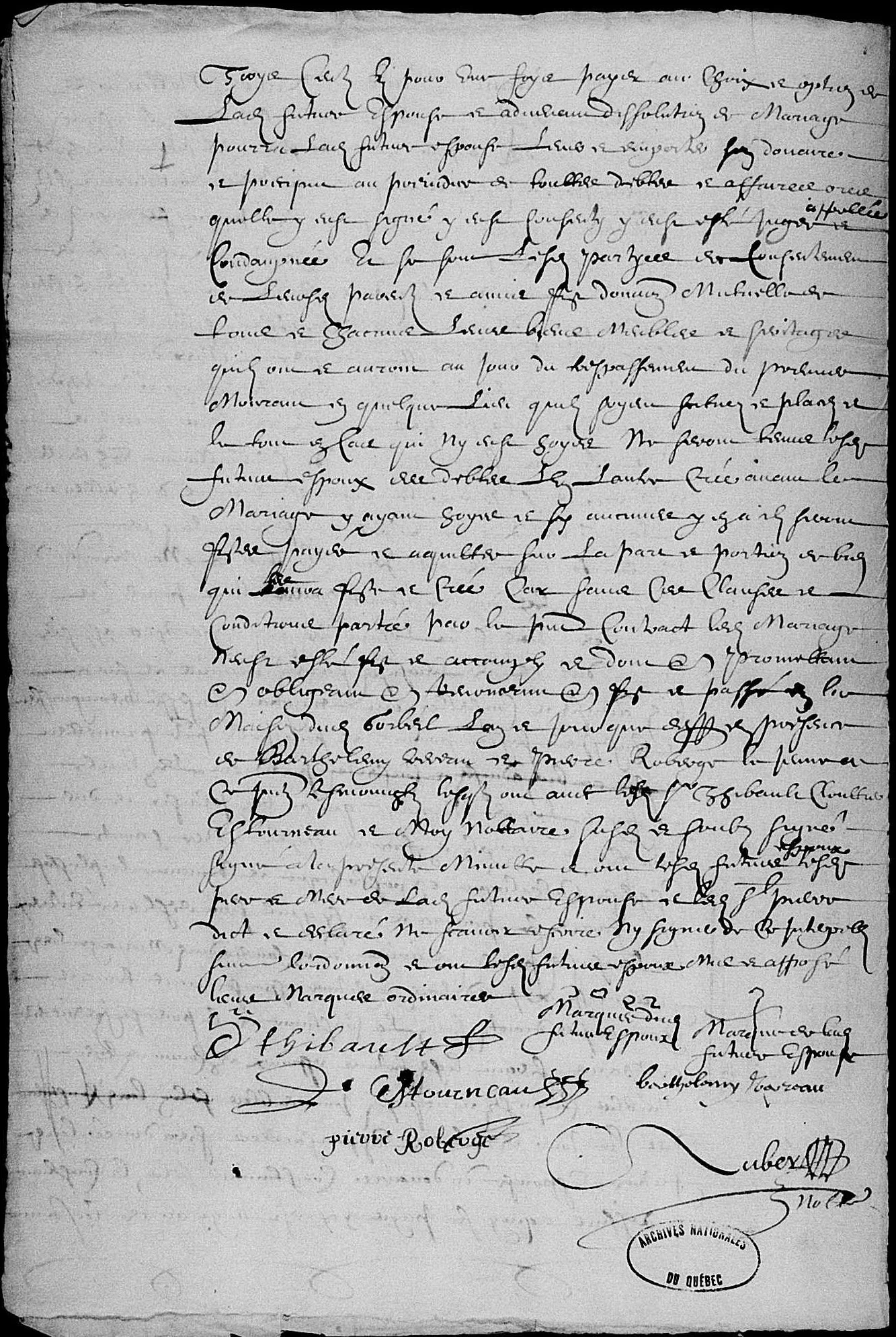

On September 30, 1668, notary Claude Auber drew up a marriage contract between Robert “Villencourt” and Marie Gobeil. He was a 23-year-old habitant; she was 13 years old. Robert’s witnesses were his former employer Guillaume Thibault and Pierre de Saint-Pierre. Marie’s witnesses were Jean Cloustier [Cloutier] and David Estourneau [Letourneau]. Additional witnesses included Barthélémy Verreau and Pierre Roberge. The contract followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. As neither Robert nor Marie could sign, they added their marks to the document, which was drafted in her parents’ home.

Legal Age to Marry and Age of Majority

In New France, the legal minimum age for marriage was 14 for boys and 12 for girls. These requirements remained unchanged during the eras of Lower Canada and Canada-East. In 1917, the Catholic Church revised its code of canon law, setting the minimum marriage age at 16 for men and 14 for women. The Code civil du Québec later raised this age to 18 for both sexes in 1980. Throughout these periods, minors required parental consent to marry.

The age of majority has also evolved over time. In New France, the age of legal majority was 25, following the Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris). This was reduced to 21 under the British Regime. Since 1972, the age of majority in Canada has been set at 18 years old, although this age can vary slightly between provinces.

The exact date of Robert and Marie’s wedding is unknown. The original parish record no longer survives, and the typewritten transcript omits the date. However, the entry is located between two marriages dated November 12, 1665, and November 18, 1669. Couples typically wed within three weeks of signing the marriage contract.

1668 marriage contract between Robert and Marie (FamilySearch) (page 1 of 2)

1668 marriage contract between Robert and Marie (FamilySearch) (page 2 of 2)

Robert’s Financial Difficulties

The year following his marriage, Robert struggled to make his lease payments to seigneur Jean François Bourdon, son of the previous seigneur Jean Bourdon. On March 15, 1669, he returned the property to its owner. His outstanding debt totalled 358 livres, which he was required to pay by the feast day of Saint-Jean-Baptiste. Robert also promised to vacate the property by Easter, leaving behind most of the farm animals, tools, and harvested crops.

On June 30, 1669, attorney general and special prosecutor Denis-Joseph Ruette-Dauteuil de Monceaux instructed notary Romain Becquet to draw up a settlement of accounts between Robert and the Bourdons. Robert acknowledged that he still owed 112 livres for the land lease.

Two years later, on August 3, 1671, Robert again appeared before notary Becquet, acknowledging that he still owed Anne Gasnier, the widow of Jean Bourdon, 98 livres for money she had lent him for clothing. This notarial document recorded Robert as an habitant of Île-d’Orléans.

Satellite view of Île-d’Orléans, where the original seigneurial lots remain clearly visible (Mapcarta)

A New Home on Île-d’Orléans

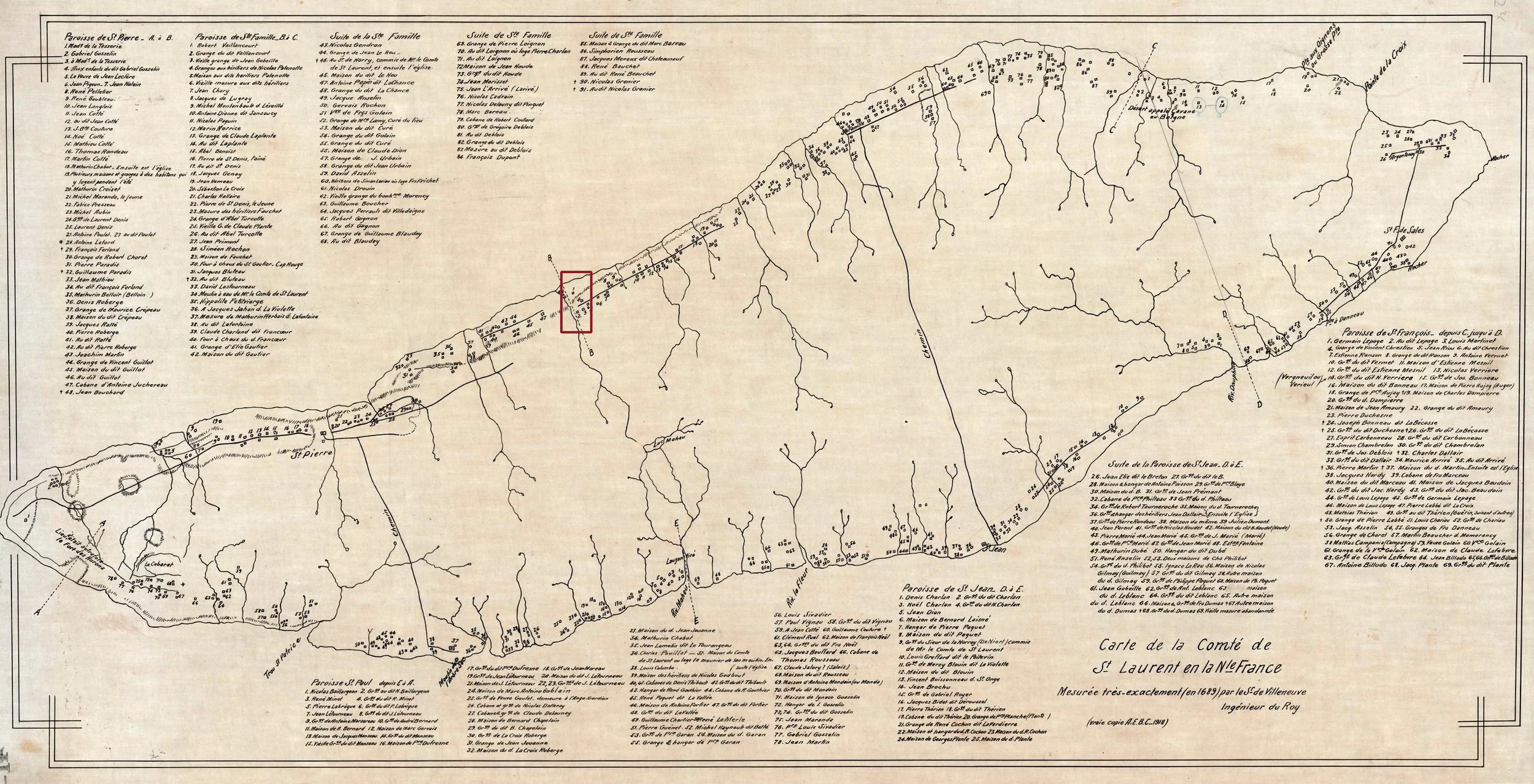

On October 28, 1669, Robert received a land concession on the north side of Île-d’Orléans from Noël Rose dit Larose, near the parish of Sainte-Famille. The property measured three arpents and three perches of frontage along the St. Lawrence River. Robert agreed to pay 20 sols in seigneurial rente for each arpent of frontage, plus [?] sols in cens and two live capons annually, payable on the feast day of Saint-Rémy. [The house (#1) and barn (#2) are shown on the 1689 map below.]

On November 7, 1669, Marie’s father, Jean Gobeil, purchased the adjacent three-arpent concession from Noël Rose dit Larose. [The Gobeil barn (#3) is shown on the 1689 map below.]

Robert, Marie, and the Gobeil family all moved to the island, likely in 1670.

Poulin seigneurial mill, built in 1668 in Sainte-Famille (photo circa 1925 by Edgar Gariépy, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Raising a Family on the Island

Given Marie’s young age at the time of her marriage in 1668, she and Robert did not have children right away. Their first child was born in 1671. The couple went on to have twelve children:

Jean (1671–bef. 1681)

Marie Anne (1672–1742)

Marie (1674–1706)

Jean Baptiste (1676–1703)

Robert (1678–aft. 1745)

Louise (1680–aft. 1698)

Paul (1682–1750)

Joseph (1684–1755)

François (1687–1754)

Marie Charlotte (1689–1759)

Marie Angélique Jeanne (1691–1717)

Bernard (1695–aft. 1750)

In 1681, Robert and Marie were enumerated in the census of New France, living on Île-d’Orléans with their five children. They owned two head of cattle and had cleared and cultivated seven arpents of land.

1681 census of New France for the Vaillancourt family (Library and Archives Canada)

On April 1, 1686, Robert leased a farm on Île-d’Orléans from Denis Roberge for three years. He was recorded as an habitant of the parish of Sainte-Famille. The farmland measured seven arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River, extending in depth to the middle of the island. It included a house, a barn, and a stable. Roberge agreed to provide Robert with twelve minots of wheat seed, two oxen, and a plow. In return, Robert promised to pay 50 minots of wheat for the first year, and 55 minots annually for the second and third years.

“Map of the County of Saint-Laurent (seigneurie of Île-d'Orléans) in New France, measured very accurately (in 1689) by Sieur de Villeneuve,” showing the Vaillancourt and Gobeil lands (#1,2,3) in red (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

On October 16, 1691, Robert purchased a plot of land on Île-d’Orléans from Claude Panneton for 300 livres. This neighbouring lot, which had previously belonged to Jean Gobeil, measured three arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River and extended to “the road that separates the middle of the island.” Robert agreed to assume the annual seigneurial dues: three livres, three sols, and two capons. [This land is shown as the “old Gobeil barn” (#3) on the 1689 map above.]

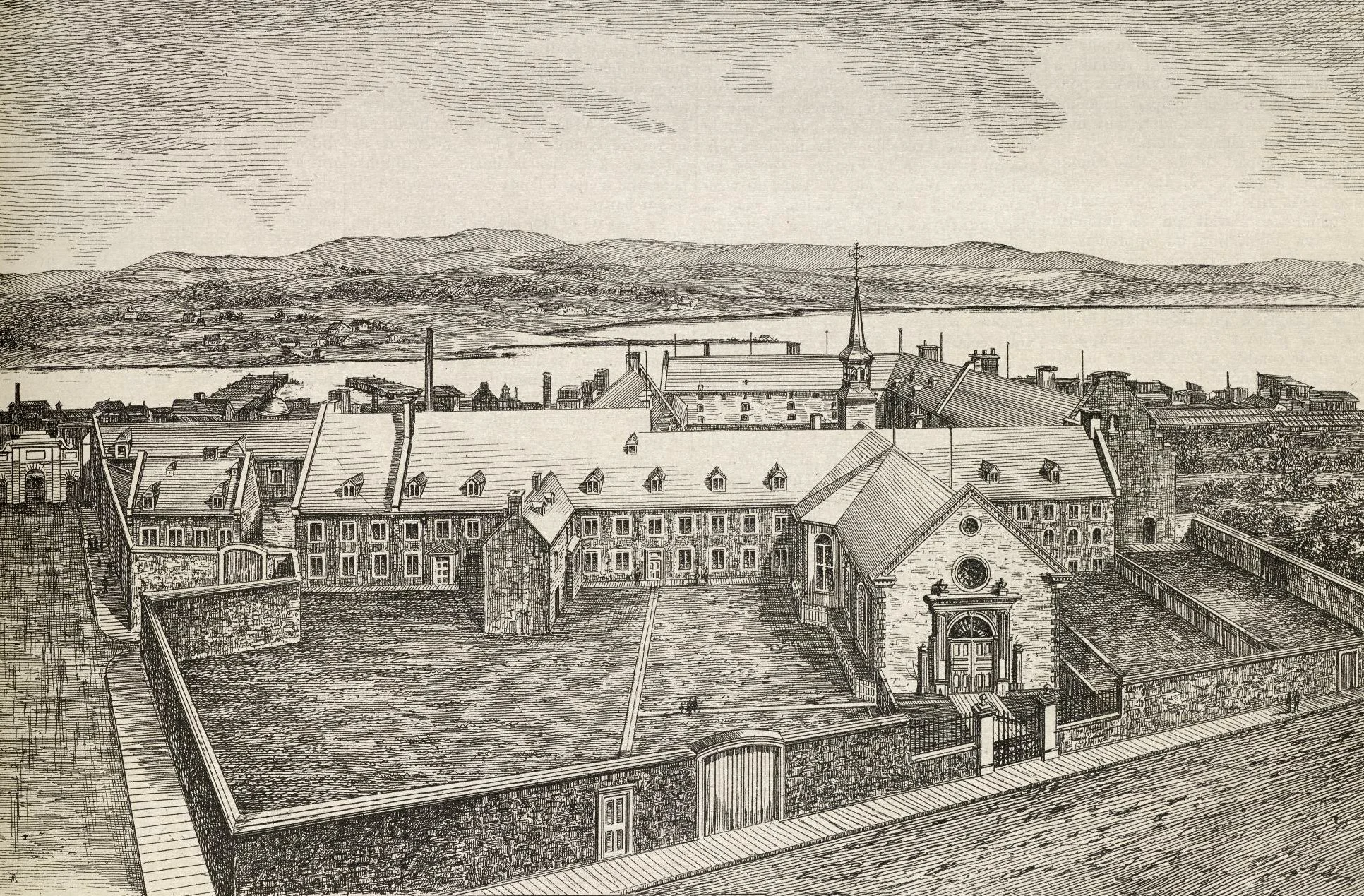

By the mid-1690s, Robert’s health began to decline. He was a patient at the Hôtel-Dieu in Québec from May 2 to 10, 1695. He returned again from October 14 to 22, 1698.

Drawing of the Hôtel-Dieu in Québec (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Death of Robert Vaillancourt

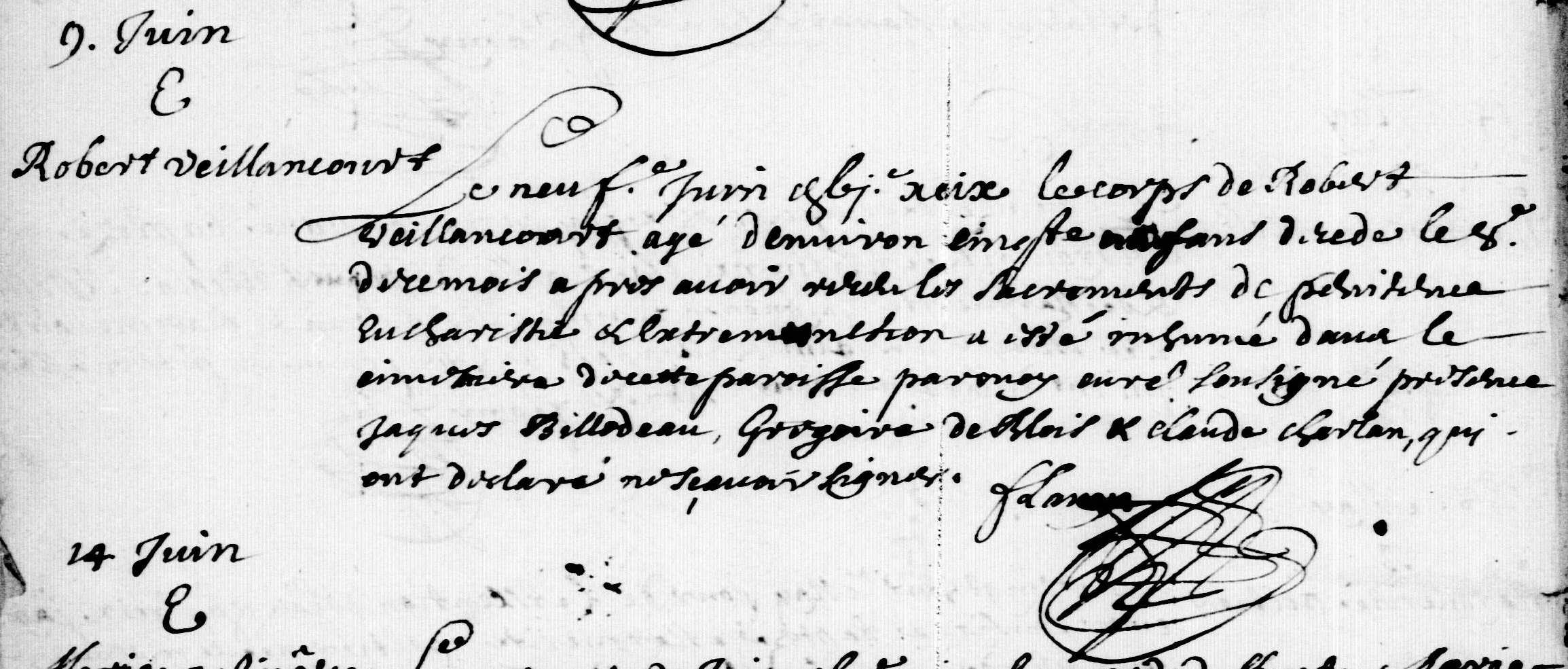

Robert Vaillancourt died at the age of 54 on June 8, 1699. He was buried the following day in the Sainte-Famille parish cemetery on Île-d’Orléans. Given his relatively young age, Robert may have been a victim of the smallpox epidemic that struck the colony in 1699.

1699 burial of Robert Vaillancourt (Généalogie Québec)

After her husband’s death, Marie began planning her succession. On February 26, 1700, she transferred the land Robert had purchased in 1691 to their son Jean Baptiste, declaring that she “could no longer work the land nor pay the rente, for which she was in arrears for the past three years.” Jean Baptiste agreed to assume the debt and take over future payments.

After-Death Inventory

As was customary following the death of a spouse, an inventory of the couple’s community of goods was prepared. On April 12, 1700, notary Étienne Jacob and an appointed estimator visited Marie’s home to document her possessions. Although not all items were legible, the inventory included the following:

The coppersmith’s tools (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, July 2025)

Household Items and Personal Belongings: The household contained several basic items for daily living. These included a spoon mould, an old feather bed, two old blankets, a lamp, a chest, a small chest without a lock, a storage bin (huche), and two pairs of snowshoes (raquettes).

Coppersmith’s Tools: As a former chaudronnier (coppersmith), the deceased owned a number of specialized tools related to his trade. These included two hammers, two anvils, and large coppersmithing shears (grands ciseaux à chaudronner).

Farm Tools and Implements: The inventory listed numerous tools and equipment used in agriculture. These included four hoes, four axes, a manure hook, two old sickles, a small saw (sciotte), three augers (tarières), an old billhook (serpe), a plough, a cart with wheels, and two sleds (traînes). Chains, shovels, hooks, wedges, scythes (faulx), and a brace (vilebrequin) were also mentioned, along with a grill for cooking.

Stored Provisions and Harvested Crops: The household had a modest supply of food and harvested goods: approximately two pounds of butter, 40 minots of wheat, six minots of flour, two minots of peas, two minots of oats, and one minot of barley.

Livestock and Buildings: Livestock on the property included two aged oxen, two cows, two two-year-old heifers, a mare, three piglets, seven hens, and a rooster. The farm also had an old shed, an old stable, one unfinished house, and another older dwelling.

Additional Items: The inventory mentioned around twenty small debts, some important documents and contracts, and information related to their land holdings.

Death of Marie Gobeil

The exact date of Marie Gobeil’s death is unknown, as her burial record has not been found. She died sometime after February 9, 1711. On that date, during the marriage of her daughter Charlotte, she was not listed as deceased in the marriage record—whereas Robert was.

A Lasting Legacy

Rue Vaillancourt, Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont (Google)

Robert Vaillancourt and Marie Gobeil were among the early settlers of Île-d’Orléans, where they raised a large family and contributed to the development of the Sainte-Famille parish. Through periods of hardship, land transactions, and changing fortunes, they built a legacy that extended far beyond their lifetimes. Generations of Vaillancourt descendants across Québec, Canada, and the United States trace their roots to this pioneering couple.

In 1945, a street in Saint-Nicolas-d’Aliermont was named in Robert’s honour: Rue Vaillancourt.

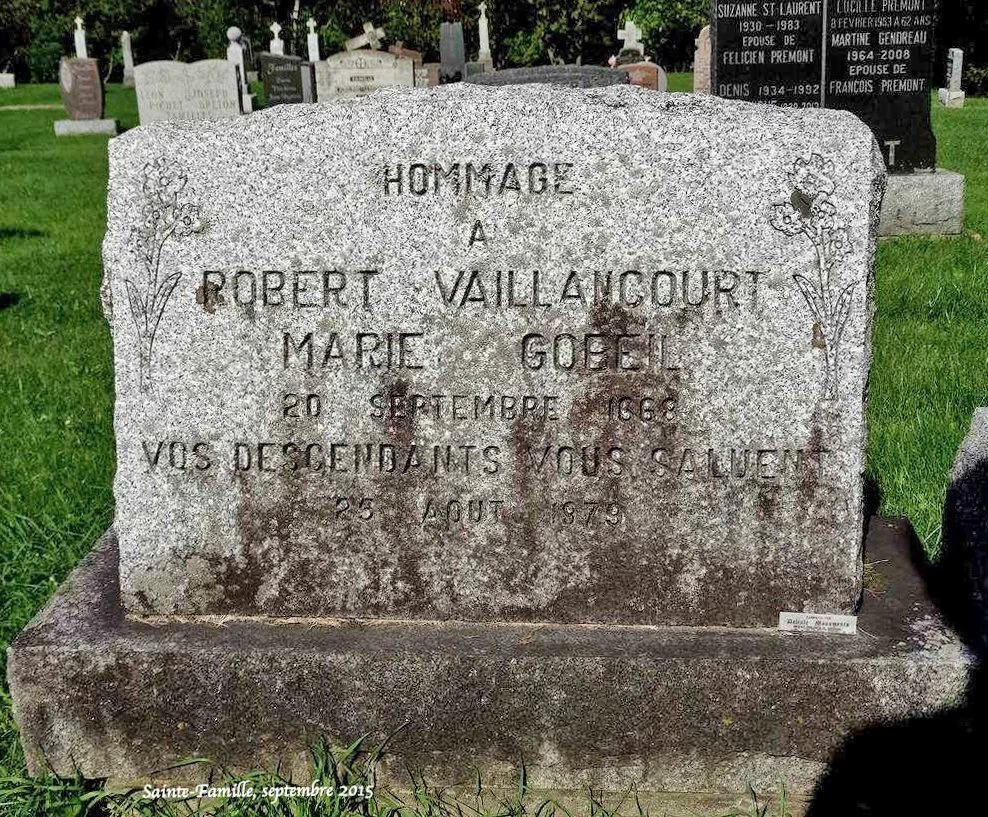

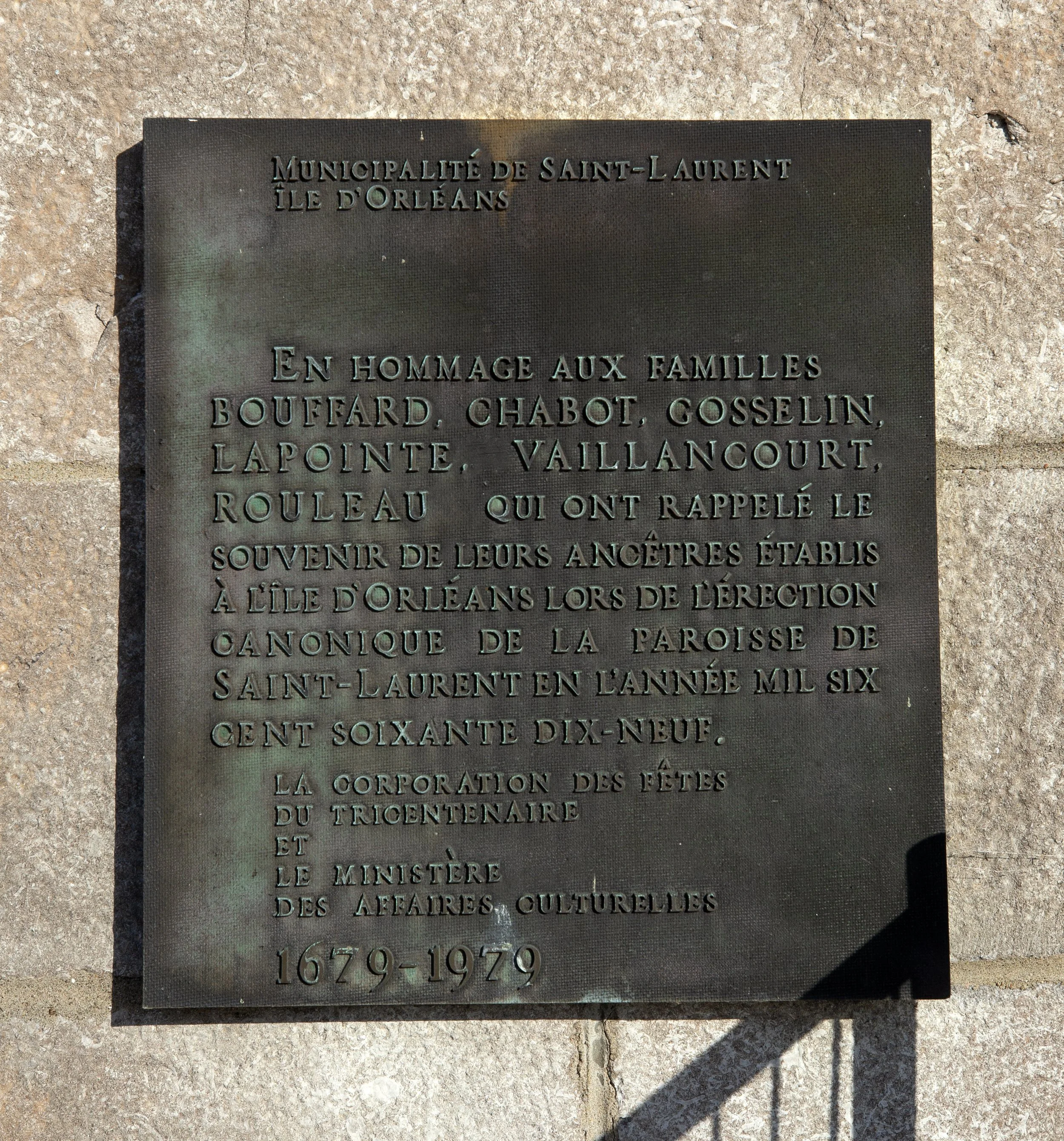

A memorial to Robert and Marie exists in the Sainte-Famille parish cemetery, and a commemorative plaque has been affixed to the parish church in Saint-Laurent, both on Île-d’Orléans.

Homage to Robert Vaillancourt and Marie Gobeil (2015 photo by Jacques Bernier, Cimetières du Québec)

Plaque on the parish church of Saint-Laurent on Île-d’Orléans (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“Saint-Nicolas-d'Aliermont - 01/01/1615-15/01/1670," digital images, Archives de la Seine-Maritime (https://www.archivesdepartementales76.net/ark:/50278/1b9160805a75291a0fd8ce89a671da45/dao/0/74 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), baptism of Robert Vaillancourt, 3 Oct 1644, Saint-Nicolas-d'Aliermont, image 74 of 169.

“Niort — Saint-Liguaire — Baptêmes, Mariages (1609-1668) — E DEPOT 23 / 2 E 187-387," digital images, Archives Départementales des Deux-Sèvres (https://archives-deux-sevres-vienne.fr/ark:/58825/vta607297f850b6cdd3/daogrp/0/187 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), baptism of Marie Gobeil, 25 Jan 1655, Saint-Liguaire (Sainte-Marie-Madeleine), image 187 of 229.

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 29 Jul 2025), household of Guillaume Thibau, 1666, Beaupré, page 46 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Ibid., household of Jean Gobeil, 1666, Beaupré, page 62 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), household of Guillaume Thibault, 1667, côte de Beaupré, page 142 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Ibid., household of Jean Gobeil, 1667, côte de Beaupré, page 141 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), household of Robert de Liancourt, 14 Nov 1681, Île-d’Orléans, page 312 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, mariages et sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/30171 : accessed 30 Jul 2025), marriage of Robert Villancourt and Marie Gobeil, 1668, Château-Richer (La-Visitation-de-Notre-Dame) ; citing original data : Institut généalogique Drouin and PRDH.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/33108 : accessed 30 Jul 2025), burial of Robert Veillancourt, 9 Jun 1699, Ste-Famille (Île d'Orléans).

“Archives de notaires : Romain Becquet (1665-1682),” digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=zKhJIp7qMTZnGH3TIDK_aA : accessed 29 Jul 2025), transfer of a lease of land, farm and smallholding in Saint François, by Gervais Bisson and Marie Boutet, to Robert Villencourt, 3 Aug 1668, ratified 15 Mar 1669, images 24-27 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=zKhJIp7qMTZnGH3TIDK_aA : accessed 29 Jul 2025), transfer of a lease of land, farm and smallholding in Saint François, by Gervais Bisson and Marie Boutet, to Robert Villencourt, 3 Aug 1668, ratified 15 Mar 1669, images 24-27 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=aNb5ss3Df2fFFnOEvVTSDw : accessed 29 Jul 2025), settlement of accounts between Denis-Joseph Ruette-Dauteuil de Monceaux, Attorney General and Special Prosecutor for Jean-François Bourdon and Anne Gasnier, and Robert Villencourt, 30 Jun 1669, images 181-183 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064891?docref=vmS3i5Yj1C_4s513P0vnmQ : accessed 29 Jul 2025), obligation of Robert Villencourt to Anne Gasnier, widow of Jean Bourdon, 3 Aug 1671, image 44 of 881.

"Actes de notaire, 1652-1692 // Claude Auber," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L2-61KN?i=875&cat=1175225 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), marriage contract of Robert Villancourt and Marie Gobeil, 30 Sep 1668, images 876-877 of 1,368; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L2-6BLC?cat=1175225&i=932&lang=en : accessed 29 Jul 2025), land concession to Robert Vaillancourt from Noël Rose dit Larose, 28 Oct 1669, images 933-934 of 1,368.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L2-69QS-Q?cat=1175225&i=1154&lang=en : accessed 29 Jul 2025), sale of land located on Île-d’Orléans on the north side by Noël Rose dit Larose to Jean Gobeil, 7 Nov 1669, images 1,155-1,157 of 1,368.

"Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3NF-49X6-2?cat=1171570&i=1154&lang=en : accessed 30 Jul 2025), farm lease by Denis Roberge to Robert Vaillancourt, 1 Apr 1686, images 1,155-1,157 of 1,327.

“Archives de notaires : Gilles Rageot (1666-1691),” digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4083923?docref=wlLwgWbc32P2pwXSYHQLEA : accessed 30 Jul 2025), land sale by Claude Panneton to Robert Villancourt, 16 Oct 1691, images 1,255-1,256 of 1,348.

"Actes de notaire, 1682-1709 // François Genaple," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-VQQC-M?cat=1168969&i=2767&lang=en : accessed 30 Jul 2025), land transfer by Marie Gobeil to Jean Veillancour, 26 Feb 1700, images 2,768-2,770 of 3,410.

"Actes de notaire, 1680-1726 // Etienne Jacob," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3NX-W678?cat=678814&i=2878&lang=en : accessed 30 Jul 2025), inventory of Robert Vaillancourt, 12 Apr 1700, images 2,879-2,886 of 3,044.

"Registre Journallier Des Malades qui viennet ; sortent ; et meurent dans Lhotel Dieu de Kebec," digital images, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_31480121?pId=30530816 : accessed 30 Jul 2025), entry for Robert Villancour, 53, entered 2 May 1695 ; citing original data : Drouin Collection, Institut généalogique Drouin.

Ibid. (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_31480181?pId=30530816 : accessed 30 Jul 2025), entry for Robert Villeancour, 55, entered 14 Oct 1698.

“Vaillancourt, Robert,” online database, Fichier Origine (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/vaillancourt : accessed 29 Jul 2025), entry for Robert Vaillancourt, data sheet 244015.

“Gobeil, Marie,” online database, Fichier Origine (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/gobeil-4 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), entry for Marie Gobeil, data sheet 241813.

Christopher Moore, "Making it Count," Canada's History (https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/business-industry/making-it-count), posted online 12 Mar 2021; original appeared in the Apr-May 2021 issue of Canada's History.

Jacqueline Sylvestre, "L’âge de la majorité au Québec de 1608 à nos jours," Le Patrimoine, Feb 2006, volume 1, number 2, page 3, Société d’histoire et de généalogie de Saint-Sébastien-de-Frontenac.

Gérard Lebel, Nos Ancêtres volume 10 (Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, Éditions Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, 1985), 149, 152.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database, (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/en/PRDH/Famille/2412 : accessed 29 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Robert VAILLANCOURT and Marie GOBEIL, union #2412.