Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse & Charlotte Mongis

Discover the remarkable story of Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse and Charlotte Mongis, early settlers of New France. From their roots in Switzerland and Saintonge to their life on the Côte de Lauzon, this detailed biography explores their journey, legacy, and the origins of the Miville-Deschênes family in Québec.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse & Charlotte Mongis

The Story of a Soldier, Settler, and Rebel

Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse was born around 1602 in the Canton of Fribourg, Switzerland. His precise birthplace and his parents’ names remain unknown.

Location of the canton of Fribourg in Switzerland (Mapcarta)

In the early 17th century, the Canton of Fribourg was a predominantly rural and Catholic territory within the Swiss Confederacy. Governed by a patrician council of noble and bourgeois families based in the city of Fribourg, the canton maintained close ties to the Catholic Church and the House of Austria. After the Protestant Reformation swept through much of Switzerland in the 16th century, Fribourg had reaffirmed its allegiance to Catholicism, becoming a stronghold of the Counter-Reformation. The Jesuits were active in education and religious instruction, and Catholic religious life played a central role in community identity. Most of the population lived in small villages and worked as farmers, herders, or craftsmen. Life was shaped by local customs, seasonal rhythms, and communal ties, with occasional tensions arising from shifting alliances within the Confederacy and ongoing religious divides in neighbouring regions.

Located in western Switzerland, the canton bridges the country’s French- and German-speaking regions. Its capital, Fribourg (Freiburg in German), is a bilingual city on the Sarine River. Today the canton remains officially bilingual, with French spoken by roughly two-thirds of its 330,000 residents (2024) and German prevalent in the east and north.

The city of Fribourg in the Üchtland region, 17th-century map by Wenceslaus Hollar (Wikimedia Commons)

The city of Fribourg and surrounding area, 1958 photo by Werner Friedli (Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

From Switzerland to France

During the 17th century Switzerland remained neutral yet became famous for supplying mercenary troops to foreign powers, especially France. Through capitulations—formal agreements with the Crown—many Swiss, including Fribourgers, joined elite French units such as the Swiss Guards. Pierre Miville enlisted and likely fought at the Siege of La Rochelle (1627–28) under Cardinal Richelieu.

“Richelieu on the Sea Wall of La Rochelle,” 1881 painting by Henri-Paul Motte (Wikimedia Commons)

The first documentary proof of Pierre in France appears on June 24, 1635, when he witnessed the marriage of fellow Swiss Artement Artement and Marie Salomée Bloune at Saint-Hilaire in Hiers. The record describes Pierre as a “Swiss subject of Monseigneur the Cardinal, residing in Brouage.” He served among Richelieu’s thirty personal guards.

Charlotte Mongis was born around 1607 in Saint-Germain, in the old province of Saintonge, France. The exact location of Saint-Germain, or its modern name, remains uncertain, as there are three possibilities within the borders of Saintonge: Saint-Germain-de-Vibrac, Saint-Germain-de-Lusignan, and Saint-Germain-du-Seudre. Parish registers for all three begin only in the 18th century, and Charlotte’s parents’ names are unknown. Contemporary records spell her surname Mongis, Mauger or Maugis.

Pierre and Charlotte married around 1629 in Saintonge or neighbouring Aunis. They had at least seven children:

Gabriel (ca. 1630-1635)

Marie (1632–1702)

François (1634–1711)

Marie Aimée (1635–1713)

Marie Madeleine (1636–after 1708)

Suzanne (1640–1675)

Gabriel’s birthplace is unknown. The next four children were baptized at Notre-Dame in Brouage; Jacques and Suzanne at Saint-Hilaire in Hiers—both parishes now within Marennes-Hiers-Brouage, in Charente-Maritime.

1630 map of Brouage and its fortifications (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Brouage was enclosed by massive star-shaped fortifications and surrounded by swamps, making it both well-defended and difficult to access by land. Its residents—mostly soldiers, artisans, merchants, and sailors—lived under tight military oversight. Life was heavily influenced by the rhythms of the port and garrison: provisioning ships, maintaining fortifications, and supporting the army took priority. Catholicism dominated public life, especially after the fall of La Rochelle in 1628 and the suppression of Protestantism in the region.

The salt trade still played a role, but military activity now drove much of the local economy. While the city offered opportunities through its naval and strategic importance, life could be harsh—marked by strict discipline, disease outbreaks in the marshy environment, and the ever-present possibility of war.

Brouage was also the birthplace of Samuel de Champlain, explorer and founder of Québec City. Living in Brouage likely meant that Pierre and Charlotte heard of his voyages to New France, which was seen as a project of national and Catholic importance. For local families, the promise of New France could be compelling: land was abundant, the Church promoted colonization as a noble cause, and royal patronage sometimes covered the cost of the voyage. With little chance of acquiring land or improving their station at home, some families were tempted by the possibility of a new start across the sea—following in the footsteps of Champlain.

1632 map of New France by Samuel de Champlain (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

A Short Stay in La Rochelle

After Cardinal Richelieu died in 1642 and his nephew-successor in 1646, Pierre Miville was likely relieved of his guard duties by Brouage’s new lieutenant-general, who preferred to surround himself with loyal appointees. Around 1646 the Miville family moved to La Rochelle, hoping to establish a home there. On November 5, 1646, Pierre leased a fifty-foot lot along the town walls near the Vérité Gate in Saint-Nicolas for 16 livres a year. He undertook to build a house within twelve months and hired a mason the same day.

The Quai Valin marina in La Rochelle, with the Saint-Nicolas neighbourhood behind it, 2023 photo (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

By December 1647, however, Pierre had not met the terms of his lease. Although construction had begun, the house remained unfinished. Perhaps short of funds—or tempted by a better prospect—he abandoned the project.

Crossing to New France

Deciding on a fresh start, the Mivilles sailed for Québec—probably aboard the Grand Cardinal or the Notre-Dame. The voyage to New France was arduous. The crossing took at least six weeks, with passengers packed tightly into the ship’s hold alongside crew members, livestock, barrels of water, cannons, and assorted cargo. Space was limited, conditions were unsanitary, and seasickness was widespread. Nearly ten percent of passengers died before reaching the colony. Fortunately for the Miville family, they all arrived safely in their new home in the summer of 1649.

The family first received land in the seigneurie of Lauson, on a cliff overlooking the Plains of Abraham near today’s Saint-David-de-l’Auberivière. On October 28, 1649, Governor Louis d’Ailleboust de Coulonge granted adjoining concessions to Pierre and his fifteen-year-old son, François, each measuring three arpents of frontage by forty arpents in depth. That same day Pierre also obtained a 26-arpent parcel on the north shore of the St. Lawrence, along the “Grande-Allée” between the future seigneuries of Saint-François and Saint-Jean. He never settled on this lot; it later formed part of daughter Marie’s dowry. [The original concession documents no longer exist.]

Although Pierre and his son François owned land in the seigneurie of Lauson, the family did not settle there initially due to the threat of frequent Iroquois raids. Instead, they took up residence in Québec City, in the Upper Town, where Pierre built a house on rue Saint-Louis. [He had acquired this lot from Jean de Lauson, although no official concession or lease has been located.]

On April 6, 1652, Pierre received a new concession that expanded his Lauson property by an additional four arpents of frontage. But even by 1654, the family had not yet relocated. In a declaration dated August 9, Pierre affirmed that he still resided in the house on rue Saint-Louis—describing it as measuring twenty-four by twelve toises. [A toise was an old unit of length equal to six feet.]

"The true plan of Quebec in 1663," map attributed to Jean Bourdon (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Between 1650 and 1660, all of the Miville children left the family home and married, with the exception of Jacques, who married in 1669. Marriage contracts from this period identify Pierre as a maître-menuisier (master joiner).

On August 9, 1654, Pierre sold the house on rue Saint-Louis to master gunsmith Charles Phélippeaux for 500 livres. He and Charlotte then moved to their land in the seigneurie of Lauson, where the family had been gradually constructing a home, along with two barns and a stable. A later notarial document describes the property in detail: the half-timbered, plank-roofed house contained four rooms on the ground floor, two of which had fireplaces. The barns were enclosed and covered with boards, and the stable was built in the form of a shed. Life in this area would have been isolated for the couple—the entire seigneurie had only five houses by 1663.

Return to France and New Holdings

In the fall of 1655, Pierre sailed back to France in the hopes of hiring an engagé (servant) and possibly recruiting additional colonists. He arrived in La Rochelle at the end of November and delivered several messages and letters on behalf of his friends and colleagues in New France.

Upon his return, Pierre received another land concession from Governor Jean de Lauson. On May 20, 1656, he was granted a lot in Québec’s Lower Town, located at the corner of rue Saint-Pierre and “the street that leads from the public square to the St. Lawrence River,” measuring twenty square feet. He built a house on this lot, which included one room with a chimney, a cellar and attic, and a small adjoining apartment.

Rebellion, Imprisonment and Banishment

By the early 1660s, Pierre was nearing 62 years of age and still actively managing his farm on the Côte de Lauson. Like many residents of the seigneurie, he struggled to secure hired help (engagés) despite repeated requests. The problem was systemic: newly arrived labourers were routinely appropriated by the colony’s most powerful families—Bourdon, Couillard, Giffard, Juchereau, Le Gardeur, and others—who claimed the first pick of every arriving ship. With Governor Lauson gone since 1656, there was no longer a protector for the Lauson settlers, and their legitimate demands went unanswered. Frustrated, Pierre and his neighbours decided to act. On June 30, 1664, when a ship from Normandy docked at Québec with a new group of engagés, Pierre and several other men from the Côte de Lauson marched to the landing site. Whether they intercepted the passengers on the beach or went as far as the ship remains unclear, but they attempted to take one or more workers by force. When confronted, Pierre, the clear leader of the group, physically resisted. The incident caused a stir in Québec and alarmed the colonial elite, who saw it as a direct challenge to their authority.

Two days later, on July 2, 1664, Pierre was arrested on orders from Jean Bourdon, Attorney-General and one of the very men suspected of misusing his influence to monopolize new arrivals. He was imprisoned at Château Saint-Louis and charged with sedition.

“Château Saint-Louis, circa 1694,” drawing by Edgar Gariépy, circa 1950 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

As lawyers were not permitted to practice in New France at the time, Pierre was forced to defend himself. He admitted to some actions but denied others and counterattacked, accusing his accusers—including Robert and Joseph Giffard—of hoarding engagés and abusing their power. On July 17, Pierre was brought before the Sovereign Council. Made to sit on the sellette, the low stool reserved for the condemned, he received his sentence: banishment from Québec for life and confinement to the territory of the seigneurie of Lauson, under penalty of death if he left it.

Pierre Miville on the sellette before the Conseil Souverain (Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT in July 2025)

Pierre was also fined 300 livres, to be divided between the king’s war fund and the poor of the Hôtel-Dieu. Though stripped of civil rights outside Lauson, he remained active in his community. Pierre continued to lead the local militia, and his home served as a site for Sunday Mass celebrated by travelling missionaries. His wife Charlotte managed their legal affairs. Though silenced in Québec, Pierre remained a respected figure among his fellow settlers—one who dared to stand up to the colonial elite and paid the price.

A new administration arrived in 1665—Intendant Jean Talon, Governor Daniel Rémy de Courcelles, and Lieutenant-General Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy. Although still under banishment, Pierre was determined to improve his relations with the new leadership in Québec.

On July 16, 1665, Prouville de Tracy granted a large tract of land to several men of Swiss origin: Pierre Miville, his sons François and Jacques, along with François Tisseau, Jan Gueuchuard, François Rimé, and Jean Cahusin. This area was named the Canton des Suisses fribourgeois, after Fribourg, Pierre's birthplace. The land concession spanned 21 arpents in frontage along the river and 40 arpents in depth, equally divided among the seven men. It was located in a place known as Grande-Anse, which extended approximately 15 kilometres between Saint-Roch-des-Aulnaies and Rivière-Ouelle, “15 leagues below Québec toward Tadoussac on the south side.” Pierre was clearly back in the authorities’ good graces.

1665 concession of the Canton des Suisses fribourgeois (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Pierre also became well-regarded by Intendant Talon as a boatbuilder. In 1666, he agreed to construct a new vessel for Talon, for which he received 2,000 livres upon its completion the following year.

Although the exact date of his appointment is unknown, Pierre also served as a capitaine de milice (militia captain) for the Côte de Lauson.

Life on the Côte de Lauson

The 1667 census of New France shows Pierre and Charlotte living on the Côte de Lauson with their son Jacques and a domestic servant named Le Lorain. At that time, Pierre owned eight head of cattle and had 30 arpents of “valuable” land (cleared and under cultivation).

1667 census for the Miville family (Library and Archives Canada)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Aug 2024)

In 1668, three members of the Miville family—Pierre, Charlotte, and their son Jacques—were summoned by the Conseil Souverain to testify in the case of Jacques Bigeon, who was accused of murdering Nicolas Bernard. At the time of Bernard's death, Jacques was serving as a neighbourhood captain on the Côte de Lauson. On that fateful January day, Bigeon told Jacques and another neighbour, Antoine Dupré, that Bernard had been killed by a tree Bigeon had chopped down. After examining the body and questioning Bigeon, Jacques and Dupré reported the incident to a judge in Québec. Following testimonies from several witnesses, including the Miville family, and further interrogations—along with the torture of Bigeon—he was found guilty and executed.

Death of Pierre Miville

On October 14, 1669, at 10 p.m., family patriarch Pierre Miville passed away at his home on the Côte de Lauson, “after receiving the sacraments of confession and extreme unction.” He was buried the next day in the Notre-Dame parish cemetery in Québec, where he had been banished from five years earlier.

1669 burial of Pierre Miville (Généalogie Québec)

On July 18, 1670, Jacques and François Miville, along with their mother Charlotte, made a donation to the Confrérie de Sainte-Anne in Québec for the decoration of the Sainte-Anne chapel. The donation, amounting to 80 livres and 6 sols, was given “driven by devotion to Saint Anne” and recorded by notary Pierre Duquet. In return, the Confrérie promised to hold a Requiem Mass within eight days for the repose of the soul of the late Pierre Miville.

A Disastrous Fur Trading Venture

Extract from the 1670 list of assets belonging to the dissolved Miville partnership (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In the fall of 1669, shortly after Pierre Miville’s death, his widow Charlotte and their two sons, Jacques and François, formed a partnership to engage in the fur trade. Unfortunately, the decision turned disastrous. The trio purchased merchandise on credit, valued at 4,691 livres and 16 sols, which they planned to trade with Indigenous peoples for furs. However, due to the poor conditions that year—"both because of the death and illness of the savages, and the lack of sufficient snow for hunting"—they were only able to sell 1,705 livres worth of furs, leaving them unable to repay their debt. The partnership was dissolved on July 19, 1670, with François being released from all responsibility by his mother and brother. Jacques retained ownership of a house at Rivière Saint-Jean that had been given to them. Charlotte and Jacques took on the remaining debt, as well as the unsold merchandise.

Ongoing Struggles with Debt

A year before the partnership began, Jacques had already accumulated debt with another merchant. On January 26, 1668, he acknowledged owing Jean Maheu 335 livres for merchandise.

To manage their growing debts, Charlotte and Jacques went before notary Becquet on September 14, 1670, to establish the “constitution of an annual and perpetual annuity” to Alexandre Petit, a merchant from La Rochelle. They mortgaged Pierre Miville’s estate, which included a house, barn, and stable. Petit lent them 1,670 livres, to be repaid annually at a rate of 92 livres, 15 sols, and 6 deniers.

Just four days earlier, on September 10, Jacques acknowledged a debt of 171 livres to Bordeaux merchant Jacques de Lamotte for merchandise.

The Miville sons, along with their widowed mother, continued to struggle with debts for years. Charlotte, unable to pay what she owed, was sued by Alexandre Petit. The prévôté of Québec ordered the foreclosure of her land, as well as a house in Québec. François appealed the decision, arguing that half of the land and house belonged to Pierre Miville’s children as part of their inheritance. The Conseil Souverain sided with François.

On November 5, 1674, the Miville children sold their half of the house in Québec’s Lower Town to notary Gilles Rageot for 150 livres. The next day, an arbitration agreement was drawn up before notary Duquet to resolve the debts of the Miville estate with creditors, namely Charles Bazire and Alexandre Petit. Three arbitrators were appointed to settle the matter and avoid draining the estate’s funds in notarial fees. Both parties agreed to abide by the future arbitration ruling.

The day before, on November 4, 1673, Jacques had transferred a plot of land to Pierre Normand de Labrière. The land measured six arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River. It remains unclear whether any payment was made or what Normand agreed to in exchange for the land.

On December 17, 1674, one of the Mivilles' creditors, Charles Bazire, successfully petitioned for François to be appointed curator “for the person and property” of his mother, Charlotte, due to her dementia. François was granted the authority “to pursue or defend the rights of his said mother against whomever it may please.”

Death of Charlotte Mongis

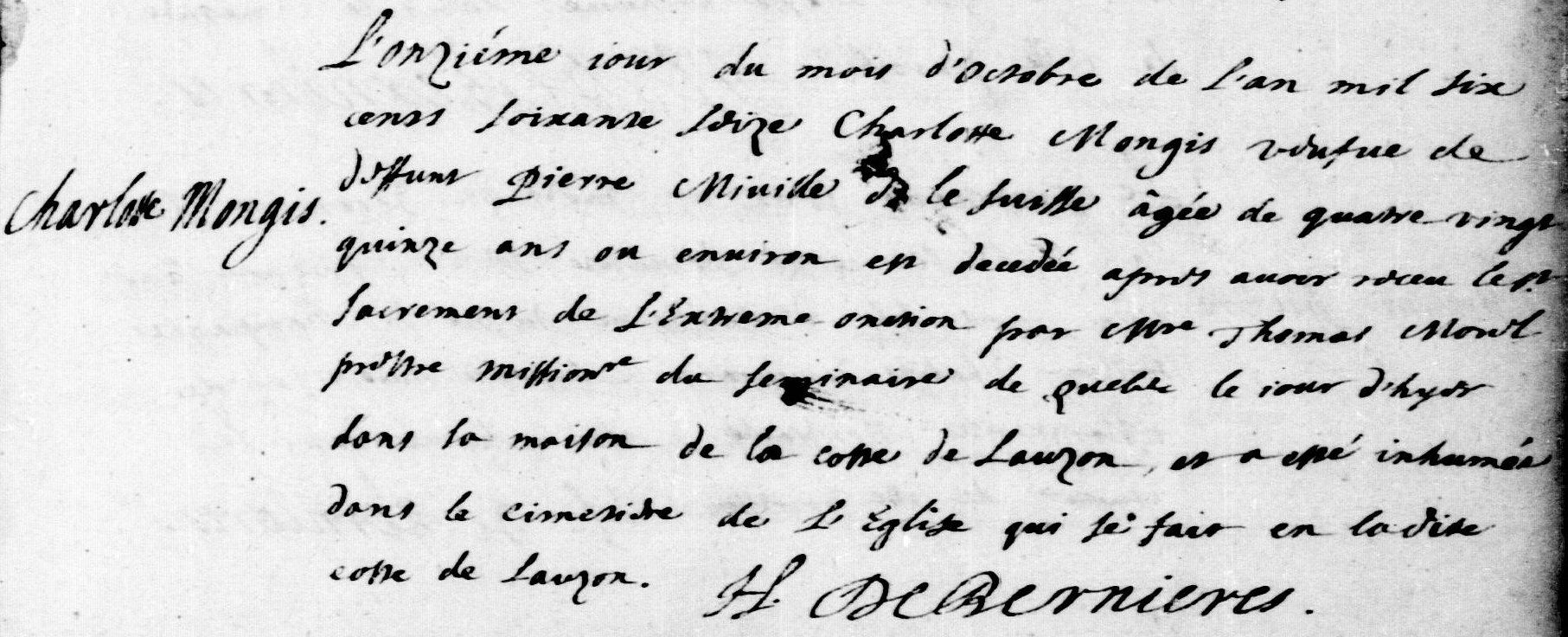

Charlotte Mongis, who had been suffering from dementia, died on October 10, 1676, “after receiving the holy sacrament of extreme unction by Monseigneur Thomas Morel missionary priest of the Seminary of Québec […] in her house on the côte de Lauzon.” She was buried the following day in “the cemetery of the church on the côte de Lauson.” The burial record erroneously indicates that she was “about 95 years old.”

1676 burial of Charlotte Mongis (Généalogie Québec)

Seven years later, unfinished business remained between Jacques Miville and his French creditors. On June 15, 1677, an agreement was signed between Jacques and his wife Catherine, and Moïse Petit, the son of Alexandre Petit, who was acting on his father’s behalf as a merchant in La Rochelle. Jacques and Catherine transferred all their assets on the Côte de Lauson, including land measuring three arpents and approximately three perches of frontage by forty arpents deep, to Petit for the modest sum of 150 livres. In turn, Petit was to give part of that sum to Charles Bazire. With this transaction, the Mivilles’ debts to both Petit and Bazire were finally settled.

The Enduring Legacy of Pierre and Charlotte

Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse and Charlotte Mongis carved out a life of determination, hardship, and resilience in the early days of New France. From Pierre’s years as a soldier in France to their family's settlement on the remote Côte de Lauson, their story reflects the broader struggles and ambitions of seventeenth-century colonists. Though Pierre was once banished from Québec for defying the colonial elite, he remained a respected leader in his community, while Charlotte upheld the family's affairs during times of difficulty. Today, countless descendants across North America trace their roots to this steadfast couple who helped shape the colony’s earliest foundations.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Raymond Ouimet, Pierre Miville : un Suisse en Nouvelle-France (Québec, Les éditions du Septentrion, 2020).

“Actes de notaire, 1665-1682 : Romain Becquet,” digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064891?docref=iV0K-BnCZHJ5R3M1hHoKdw%3D%3D : accessed 1 Jul 2025), claim against the estate of Pierre Miville dit le Suisse, 25 Aug 1672, images 725 to 730 of 881.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064891?docref=iV0K-BnCZHJ5R3M1hHoKdw%3D%3D : accessed 1 Jul 2025), réclamation contre succession de Pierre Miville dit le Suisse, 25 Aug 1672, images 725 to 730 of 881.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=KXmcijcIBp8tUjPuu5T-wg : accessed 10 Sep 2024), dissolution of partnership between Charlotte Montgy, François Minville and Jacques Miville-Deschesne, 19 Jul 1670, images 423 to 426 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=d3DdpHOWmEpR2KpUCSkiVQ : accessed 10 Sep 2024), dissolution of partnership between Charlotte Montgy, François Minville and Jacques Miville-Deschesne, 14 Sep 1670, images 806 to 808 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=oqP9Uz4L-pg8HLIoYKoaHw : accessed 11 Sep 2024), obligation of Jacques Miville-Deschesne to Jacques de Lamotte, 10 Sep 1670, image 804 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064892?docref=IW-zaQy29lm34r9GNdP9yg : accessed 10 Sep 2024), sale of half a house in Québec by François Miville (and his siblings) to Gilles Rageot, 5 Nov 1674, images 734 and 735 of 954.

“Actes de notaire, 1663-1687 : Pierre Duquet,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-YB2Z?cat=1175224&i=1310 : accessed 10 Sep 2024), donation to the Confrérie de Sainte-Anne by Charlotte Maugis, François Miville and Jacques Miville Deschesnes, 18 Jul 1670, images 1311 to 1313 of 2541.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-YBMV?cat=1175224&i=2009 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), transaction between Charles Bazire, Alexandre Petit and François Miville, 6 Nov 1674, images 2010 to 2011 of 2541.

“Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 : Gilles Rageot,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVF-YQCX-J?cat=1171570&i=362 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), obligation from Jacques Miville to Jean Maheut, 26 Jan 1668, images 363 to 364 of 1443.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DQ-JZN1?cat=1171570&i=887 : accessed 6 Sep 2024), land transfer from Jacques Miville Deschesne to Pierre Normand de Labrière, 4 Nov 1674, image 888 of 3381.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DQ-JZ54?cat=1171570&i=1391 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), agreement between Moïse Petit and Jacques Miville and Catherine Baillon, 15 Jun 1674, images 1392 to 1396 of 3381.

"Fonds Intendants - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/90790 : accessed 2 Jul 2025), "Déclaration faite au papier terrier de la Compagnie des Indes occidentales par François Miville, faisant pour Pierre Miville, son père, laquelle déclaration étant relative à une place sise rue Saint-Pierre, en la Basse-Ville de Québec, sur laquelle il y a une maison," 23 Nov 1667, reference E1,S4,SS2,P41, Id 90790.

"Fonds Conseil souverain - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/398336 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Concession par Alexandre de Prouville, chevalier, seigneur de Tracy, conseiller du Roi en Ses conseils, lieutenant général pour Sa Majesté en l'Amérique méridionale et septentrionale, tant par mer que par terre, à Pierre Miville, François Rimé, François Miville, Jacques Miville, François Tisseau, Jean Gueuchard et Jean Cahusin, tous Suisses, d'une terre située au lieu nommé la Grande-Anse, sise quinze lieues au-dessous de Québec en allant vers Tadoussac, du côté du sud," 16 Jul 1665, reference TP1,S36,P38, ID 398336; citing original data : Pièce provenant du Registre des insinuations du Conseil supérieur de Québec établi en Canada par l'Édit du Roi Louis XIV du mois d'avril 1663 (28 décembre 1628 au 1er mai 1682), volume A, f. 14. Publiée dans le Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, volume XX, p. 233. Pour consulter les pages du registre permettant de comprendre son contexte de création, sa valeur juridique et administrative, son contenu ou l'historique de sa conservation, voir les pièces TP1,S36,PAA et TP1,S36,PKK.

Ibid. (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/398760 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Procès de Jacques Bigeon, environ 50 ans, cordier (celui qui fabrique ou qui vend des cordes), natif de La Flotte à l'île de Ré, paroisse de Sainte-Catherine, accusé du meurtre de Nicolas Bernard," 28 Jan 1668 - 26 Apr 1668, reference TP1,S777,D109, ID 398760; citing original data : Dossier provenant du registre Procédures judiciaires Matières criminelles, tome I : 1665-1696, f. 46-86b. Pour les arrêts prononcés sur cette cause par le Conseil souverain de Québec, les 23 et 26 avril 1668, voir les pièces TP1,S28,P575; TP1,S28,P577.

Ibid. (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/400753 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Appel mis au néant de la sentence rendue par le lieutenant général, en date du 2 septembre 1672, entre les héritiers du défunt Pierre Miville et Moïse Petit, marchand et procureur d'Alexandre Petit et correction de la dite sentence," 2 May 1673, reference TP1,S28,P817, ID 400753 ; citing original data : Pièce provenant du Registre no 1 des arrêts, jugements et délibérations du Conseil souverain de la Nouvelle-France (18 septembre 1663 au 19 décembre 1676), f. 169v-170.

Ibid. (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/401112 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Nomination de François Miville comme curateur à la personne et aux biens de Charlotte Mongis, sa mère, veuve de feu Pierre Miville, vu qu'elle est démente, sur la requête de Charles Bazire, agent de la Compagnie des Indes occidentales et Moïse Petit, procureur d'Alexandre Petit, marchand," 17 Dec 1674, reference TP1,S28,P1023, ID 401112; citing original data : Pièce provenant du Registre no 1 des arrêts, jugements et délibérations du Conseil souverain de la Nouvelle-France (18 septembre 1663 au 19 décembre 1676), f. 215.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), entry for Pierre Miville, 1667, Côte de Lauzon, Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, mariages et sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/69063 : accessed 6 Sep 2024), burial of Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse, 15 Oct 1669, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/69280 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), burial of Charlotte Mongis, 11 Oct 1676, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

France Archives, Archives nationales, Châtelet de Paris, Y//226-Y//230, Insinuations (1673-1676), notice 679, folio 287, https://francearchives.fr/fr/facomponent/35637ff94456aaafea70af840e903df9f7197c06 : accessed 19 May 2020).

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/86336 : accessed 1 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Pierre MIVILLE and Charlotte MAUGER, union 86336.

Thomas J. Laforest, Our French-Canadian Ancestors vol. 27 (Palm Harbor, Florida, The LISI Press, 1998), 108-121.