Tanner

Did you ancestor work as a “tanneur,” or tanner, in New France? Discover the history of tanners in the colony, from François Byssot’s first tannery at Pointe-Lévy in 1668 to the “tannery villages” of Montréal. Learn how families like the Lenoir dit Rolland transformed animal hides into leather for shoes, boots, and harnesses, and how Indigenous tanning traditions shaped the craft. This article explores the demanding tanning process, key families, and neighbourhoods where the trade flourished—bringing the story of our leatherworking ancestors to life.

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Le tanneur | The Tanner

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (Sep 2025)

A tanneur, or tanner, transformed animal skins into leather through the laborious process of treating hides with tan or tannin—powdered tree bark that gave the profession its name. These artisans worked in tanneries, typically relegated to town outskirts near rivers or streams due to the trade's noxious odours. By the mid-17th to 18th centuries, this malodorous but vital trade supplied the colony with leather for shoes, harnesses, and other goods indispensable to the economy.

Tanning began in New France during the 17th century in Québec and Montréal. Initially, leather artisans imported skins from France, but as local butchers established themselves, colonial tanners increasingly processed domestically sourced hides. While sheepskin and cattle hides formed the industry's foundation, hunters and fishermen supplied exotic materials like walrus, seal, moose, deer, and bear skins.

New France's First Tanneries

The colony’s earliest tannery was established in 1668 in the seigneurie of Pointe-Lévy, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River across from Québec City. This tannery was built by François Byssot de la Rivière on a land concession he received in 1648. He had a lock constructed in the stream separating his property from that of Guillaume Couture, and a wooden canal that supplied water to the tannin vats. Byssot received financial support from Intendant Jean Talon, who advanced 3,268 livres from the royal treasury.

Talon's objective centred on colonial self-sufficiency in leather goods. By the early 1670s, he noted that “nearly a third of the shoes [in Canada] are made from native leathers.” The Pointe-Lévy tannery specialized in processing locally available hides – cattle and calf skins as well as wild game and even marine mammal hides from elk, deer, porpoise, and seal – transforming them into leather for shoes, boots, ankle-boots, harnesses, muffs, and covers for chests and trunks. Talon ordered large quantities of shoes for the troops from Byssot’s operation, which by 1673 was producing about 8,000 pairs of shoes per year for the military.

Within Québec itself, tanneries gradually appeared on the city's periphery. In 1702, Jean Larchevêque built a tannery on his brickyard property. Around 1714, the Saint-Roch district emerged as a tanning centre, particularly along De Saint-Vallier and Saint-Roch streets, where Pierre Robitaille, François Gauvreau, and Noël Giroux operated their businesses. By 1790, at least eleven tanners worked in Québec City, with six concentrated along rue Saint-Vallier—a thoroughfare that remained a leatherworking hub well into the 19th century. The city supported 33 tanneries by 1831, predominantly located in the Saint-Roch district. Notable 19th-century tanners included Jean Baptiste Hallé and François Patry.

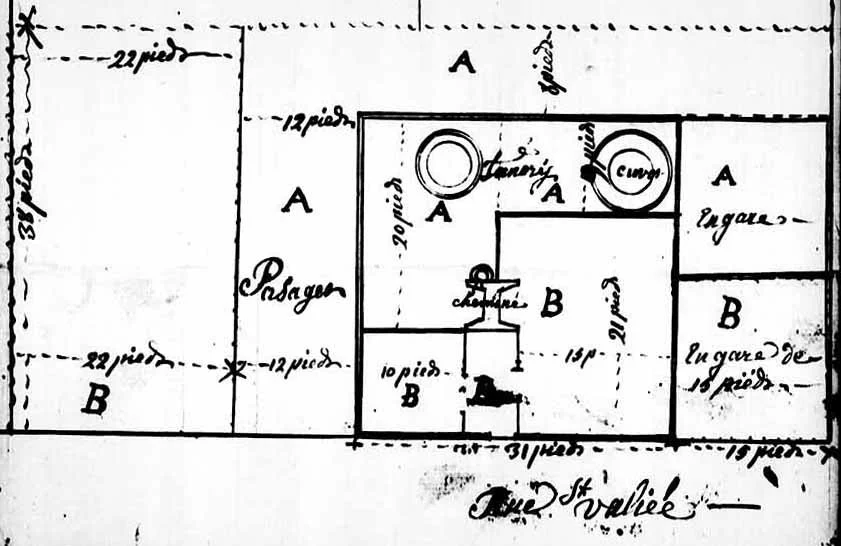

Layout of Noël Giroux’s tannery on rue Saint-Vallier in 1761 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Montréal’s Tanning Industry

Montréal's first tannery appeared in the late 17th century at coteau Saint-Pierre (today’s Saint-Henri neighbourhood), well outside the settlement’s walls. This strategic location along the fur trade route from Montréal to Lachine offered proximity to animal hides and leather workers while sparing the town from offensive odours. The area developed into a "tannery village" as multiple operations clustered along the Saint-Pierre River.

According to the Société historique de Saint-Henri, the earliest mention of a tannery in the village dates back to 1685, when merchant Jean Dedieu and tanner Jean Mouchère purchased an existing operation. In 1700, Charles de Delaunay and Gérard Barsalou acquired this tannery. Six years later, Gabriel Lenoir dit Rolland, son of a fur trader, began an apprenticeship at the establishment. His 1714 marriage to Marie Josèphe Delaunay, Charles Delaunay's daughter, united two prominent tanning families. Until his death in 1751, Gabriel Lenoir dit Rolland was a leading merchant-tanner in Montréal.

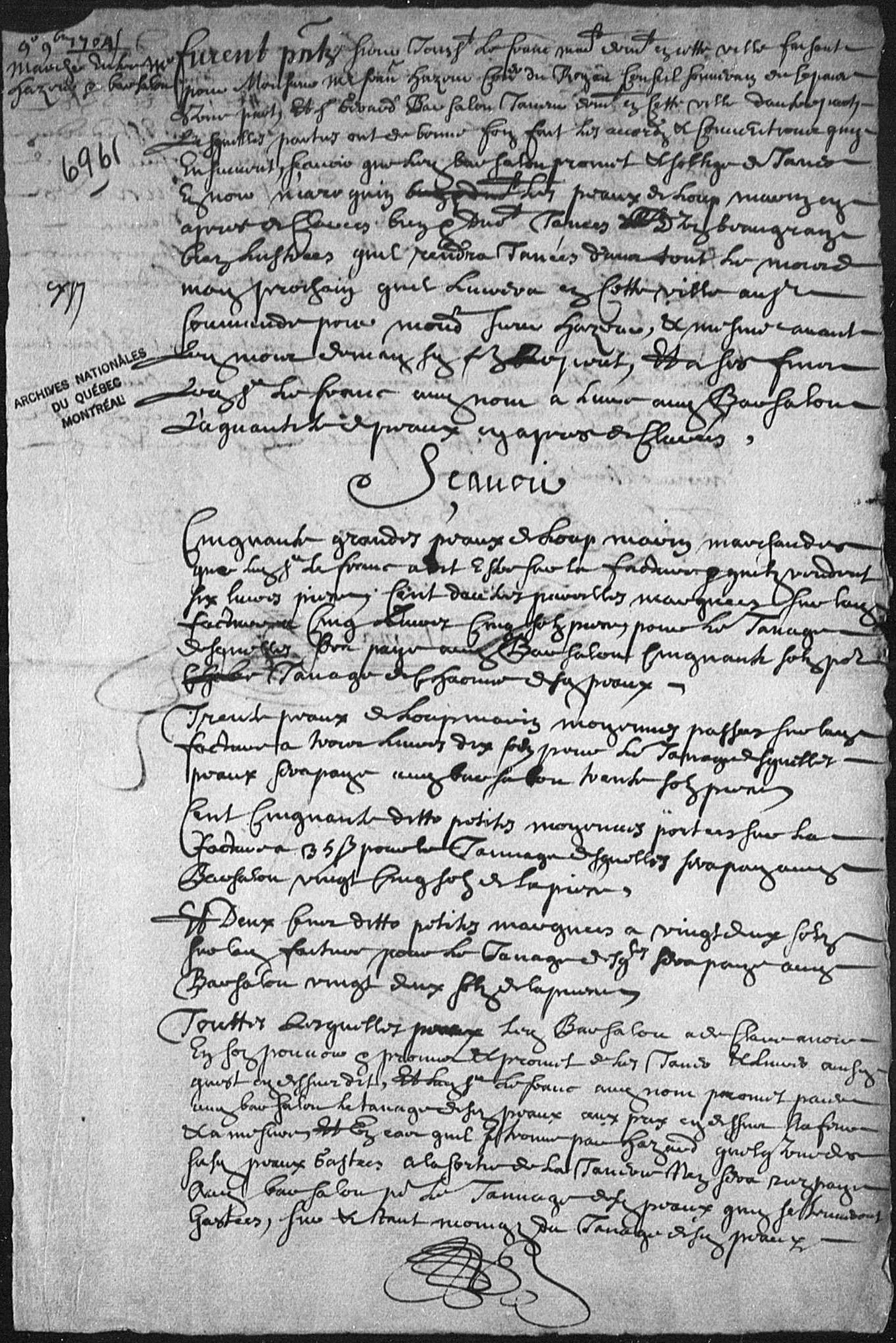

Contract for the tanning of seal skins between François Hazeur, advisor to the King on the Sovereign Council, and Gérard Barsalou, tanner, on September 9, 1704 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec) (page 1 of 2)

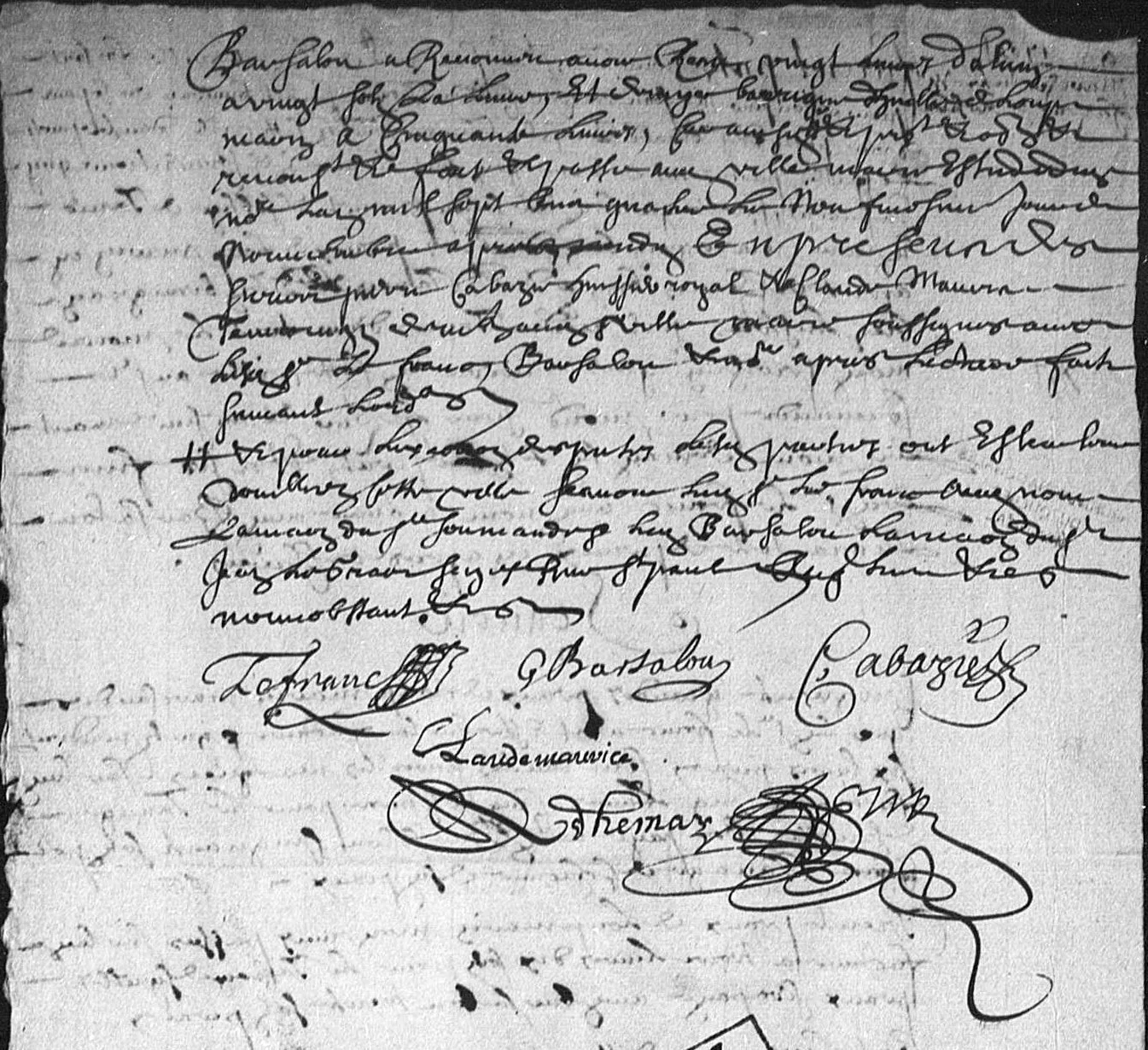

Contract for the tanning of seal skins between François Hazeur, advisor to the King on the Sovereign Council, and Gérard Barsalou, tanner, on September 9, 1704 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec) (page 2 of 2)

By 1780, coteau Saint-Pierre had evolved into a genuine leatherworking neighbourhood, known informally as the “Village des Tanneries” or “Village des Tanneries-des-Rolland.” A 1781 census recorded twelve households in the original tannery sector, with eight maintaining their own tannery facilities and six owned by Gabriel Lenoir's descendants. Multiple generations of the Lenoir dit Rolland family continued the trade, reflecting the era's common practice of integrating tanneries into family homesteads. Often a tannery was attached to the family house or at least on the same property.

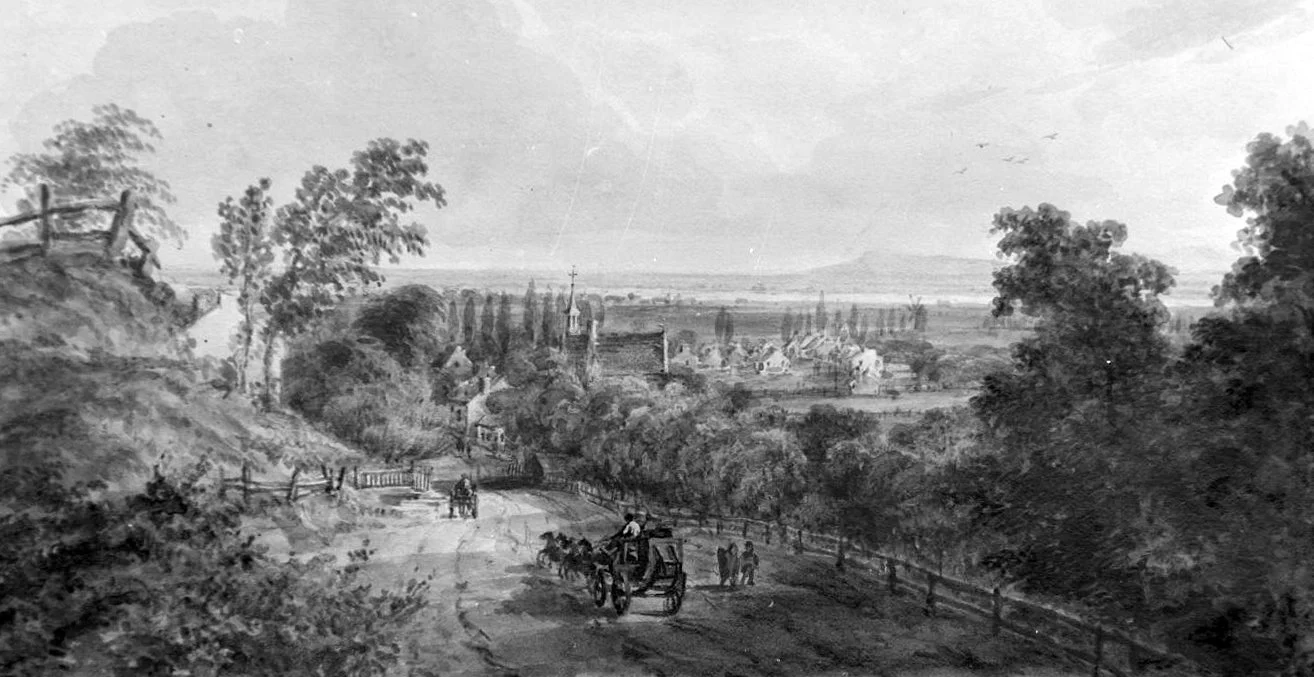

“View of the Côte des Tanneries des Rolland, October 1839,” watercolour by James Duncan (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

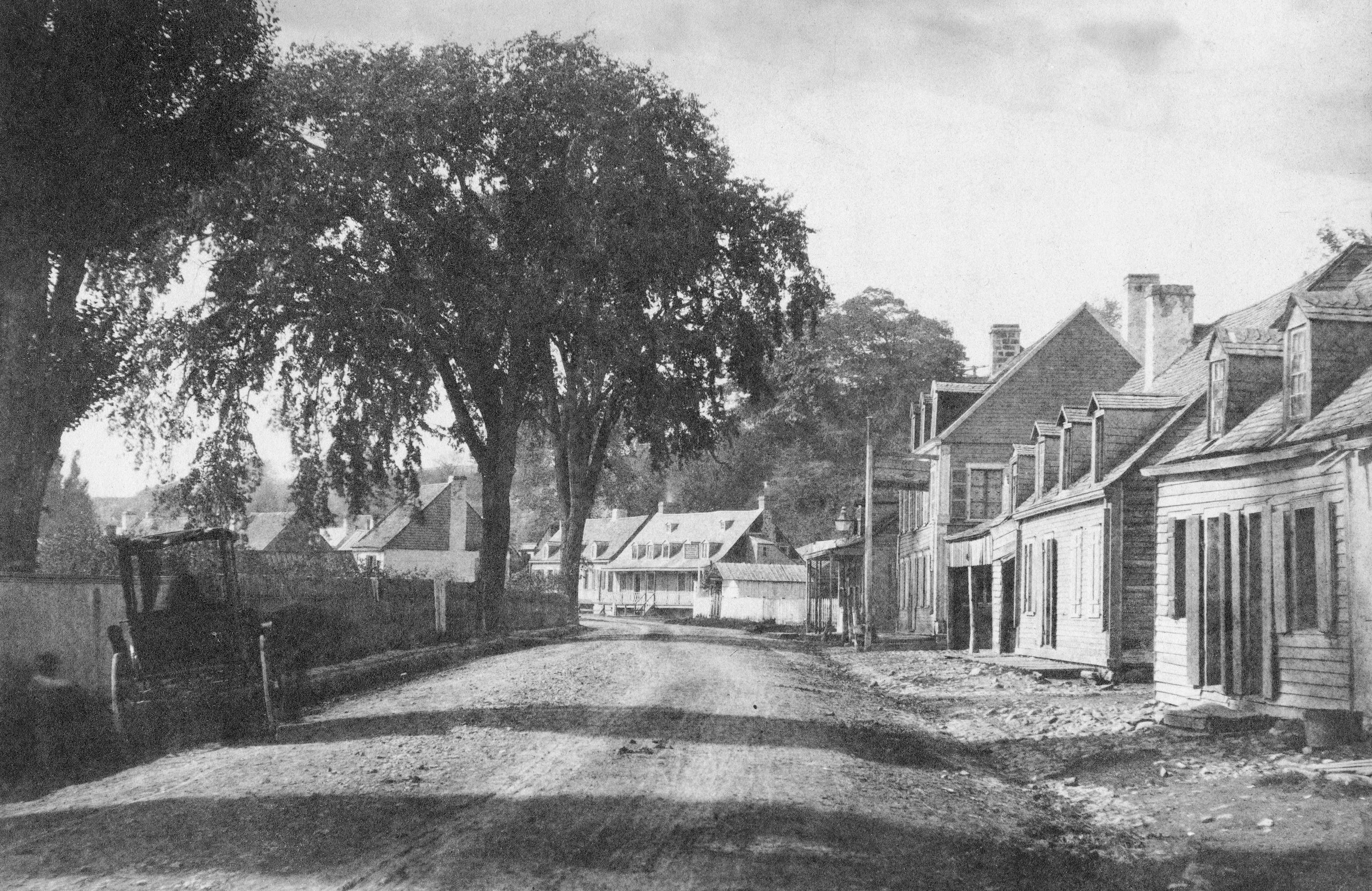

“Tanneries Village, Saint Henry, near Montreal, QC, 1859,” photo by Alexander Henderson (McCord Stewart Museum)

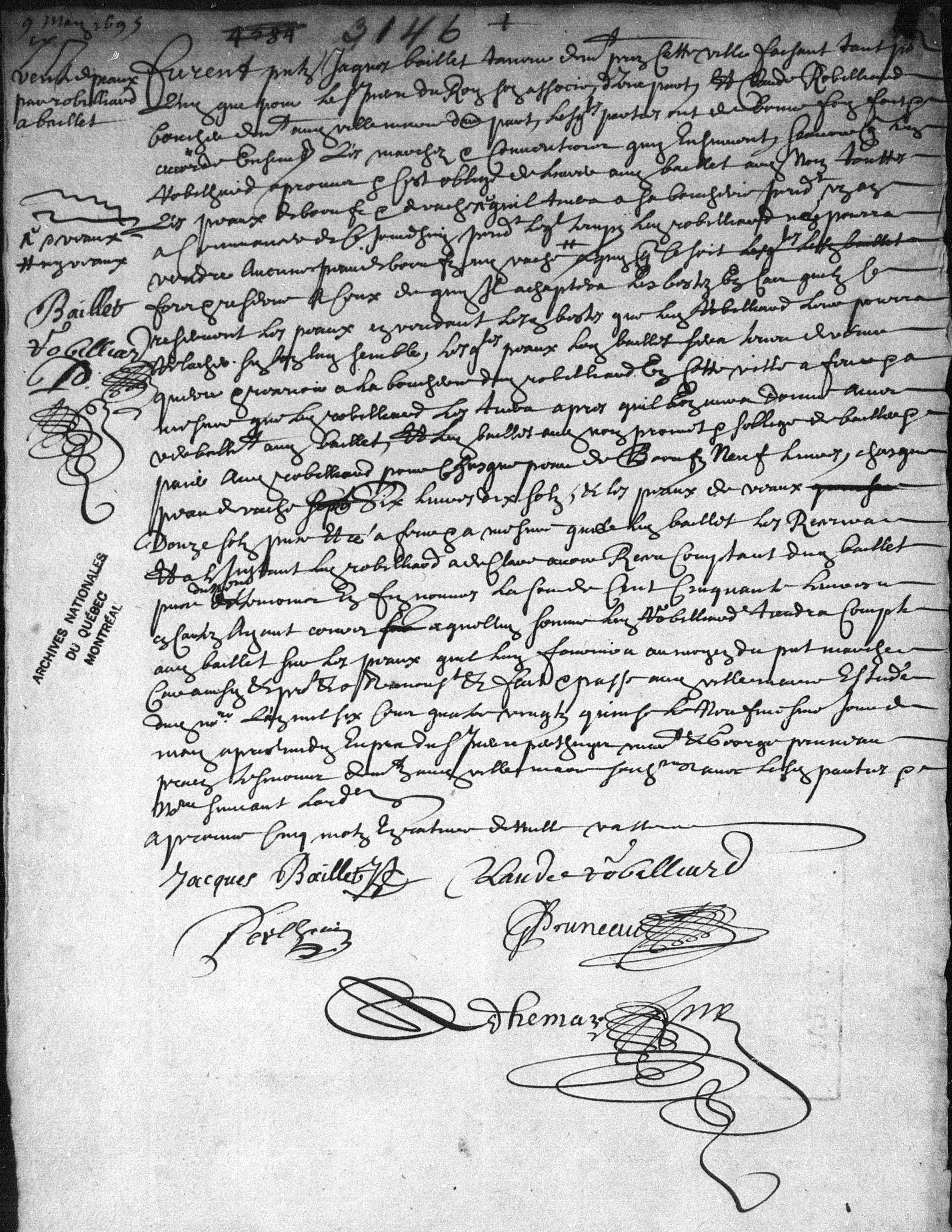

Contract for the sale of ox, cow and calf hides between Claude Robillard, butcher of Villemarie, and Jacques Baillet and Pierre Duroy, tanners, on May 9, 1695 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Meanwhile, other tanning clusters emerged throughout Montréal. On Mount Royal's eastern slope, French-born master tanner Jean-Louis Plessis dit Bélair established operations in 1714 near Côte Saint-Louis, close to a stream that later became Henri-Julien Street in today's Plateau Mont-Royal. Additional tanneries appeared nearby, leading to the creation of "chemin des Tanneries" (now Mont-Royal Avenue) and the founding of "village de la Tannerie des Bélair"—the nucleus of Montréal's modern Plateau district.

Rural tanneries also developed throughout the Montréal region. In Côte-des-Neiges, tanners Pierre Hay and François Couturier established operations, while other entrepreneurs founded tanneries elsewhere, though none matched the productivity of the coteau Saint-Pierre and Côte Saint-Louis clusters.

Government Regulation

In the time of New France, local authorities in Montreal issued several ordinances targeting tanners and their activities. An ordinance issued by Intendant Raudot on July 20, 1706, targeted tanners, shoemakers and butchers working in Montreal.

As the city of Montreal grows daily with the number of inhabitants who come to settle there, and the number of workers of all trades also increases proportionally, pending His Majesty's decision to establish trade guilds, we believe it is appropriate to prescribe certain rules, particularly for tanners and shoemakers, the observance of which will be useful to the said inhabitants, allowing the said workers to carry out their work, while at the same time giving them, in particular, the means to subsist by reducing each of them, as best we can, to the functions appropriate to their profession:

To achieve this, we order:

There shall be only two tanners in this town, namely Delaunay and Barsalot, between whom, in order that they may have equal work, the five butchers currently established here shall share equally all the hides from their establishments, unless the said tanners agree among themselves to have the said hides supplied to them by two butchers of their choice, and this for a period of six months.

That the said tanners shall be required to treat the said hides in all the ways required and necessary, so that the public may have good merchandise, on penalty of a three-livres fine for each hide, if, during the three inspections that we order to be carried out, they are found not to be of the quality specified in our present ordinance.

We forbid butchers from using any hides to make French shoes, on penalty of a three-pound fine for each hide they use, allowing them nevertheless to use a few of lesser quality to make “savage” shoes.

We also forbid them from trading these hides with the habitants of the countryside, whom we order to bring them to the market established in this city, where they shall display them and may only sell them to tanners.

And until we can establish regulations that limit each of the aforementioned workers to the work appropriate to their trade, we grant the aforementioned Delaunay, in consideration of the establishment he has created, permission to employ only three young shoemakers and one apprentice, whom he may employ in their trade. We forbid him from having more than this number, or from having them work for him in any establishments other than his own, on penalty of a fifty-livres fine, applicable as those above ordered for the maintenance of the city.

Several other ordinances followed:

February 13, 1707: “Ordinance allowing Joseph Normand to practise the profession of tanner alongside the five tanners already appointed for the city of Montreal, on condition that he employ a professional tanner in his tannery and sell only good quality leather.”

May 25, 1707: “Ordinance declaring null and void the treaty between Joseph Guyon-Desprès and Gérard Barsalou. Marie Madeleine Petit, wife of Guyon-Desprès, shall supply Barsalou with all the animal skins she kills in her butcher shop, on condition that he pay for them in cash every week, namely nine livres for an ox hide, six livres fifteen sols for a cow hide, and twelve sols for a calf hide, provided that the said hides are not damaged.”

November 3, 1707: “Ordinance allowing Charles Delaunay, a tanner in Montreal, to have four young tanners working for him and requiring him to supply good leather to shoemakers, on penalty of a fine.”

March 13, 1710: “Ordinance establishing Jean Belair as the third tanner in Montreal. The other two tanners, Delaunay and Barsalou, are forbidden from disrupting his work.”

April 25, 1712: “In view of the request presented to this Council by the shoemakers of Ville-Marie, on the island of Montreal, asking that the Court allow the tanners of said Montreal to bring to said city on holidays and Sundays only the supplies necessary for shoemakers and to distribute them as usual after the celebration of divine service, as is customary everywhere [...]. The said Council has forbidden and continues to forbid the said tanners of the said Montreal and its surroundings from bringing, cutting and distributing any leather to the shoemakers of Montreal on holidays and Sundays.”

January 29, 1713: “Ordinance allowing Joseph Normand to practise the tanning trade in Montreal under the conditions set out in Mr. Raudot's ordinance dated 13 February 1707.”

Rural Operations

Small-scale rural tanneries served local populations throughout New France. Farmer-tanners operated modest enterprises, processing hides according to community needs. Habitants bartered or paid to transform their cowhide or moosehide into leather, returning months later to collect finished materials for boots or harnesses. This system ensured even remote communities accessed locally tanned leather for essential goods.

The Tanning Process

French immigrants brought traditional tanning methods to New France, training apprentices in time-tested techniques. Mills powered by wind, water, or animals supported the multi-stage process. Tanners first soaked and softened skins in lime pits, which removed animal hair and flesh debris. To neutralize lime effects, they washed hides with diluted chicken droppings. Next, skins soaked for months in tannin basins containing hemlock or spruce bark extract (later replaced by oil and alum tanning, eventually evolving to chrome tanning). This crucial stage allowed tannins to penetrate and stabilize the leather.

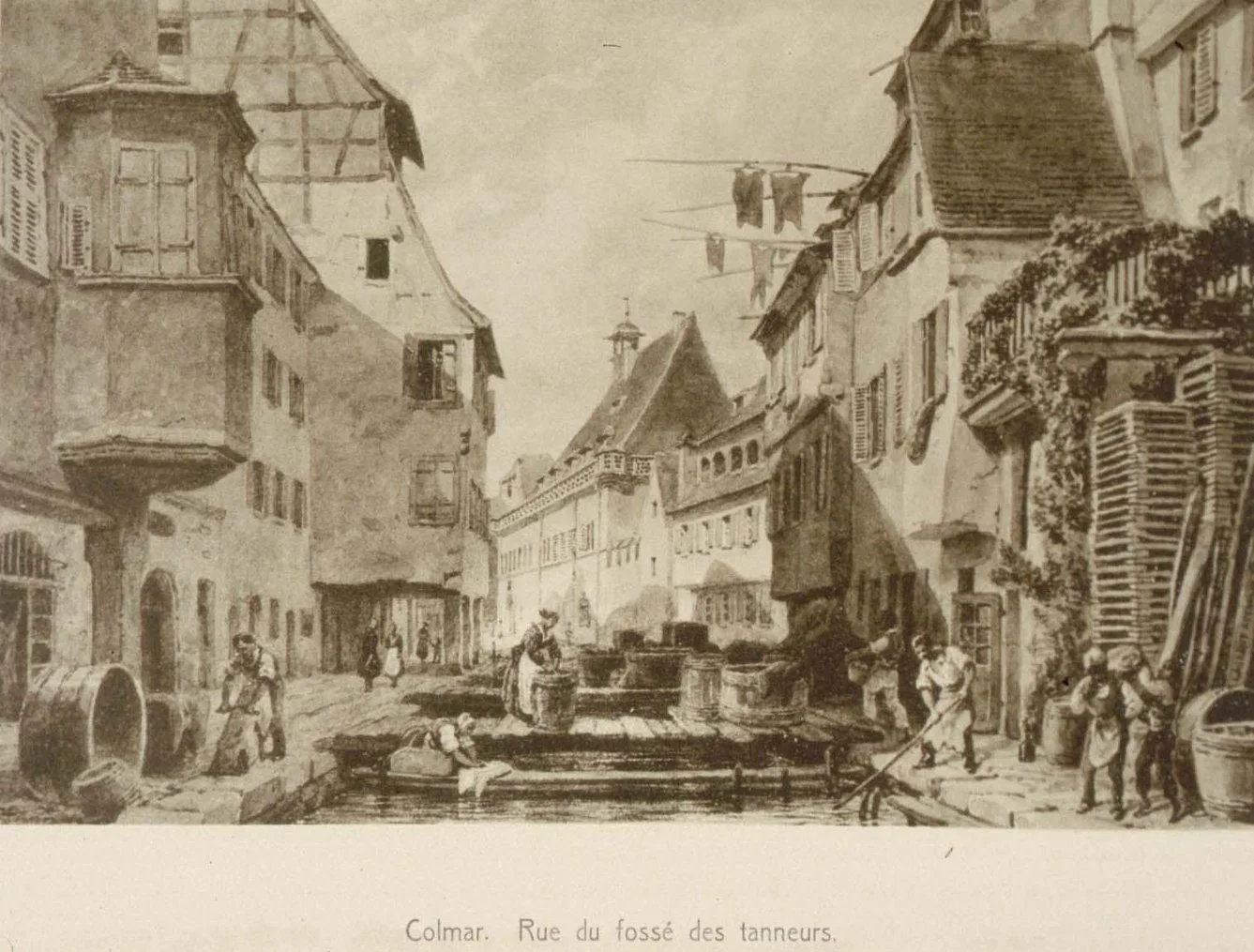

Tanners in Colmar, France ("Colmar. Rue du fossé des tanneurs," 1850 drawing by Laurent Atthalin (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (Sep 2025)

Once removed from basins, leather underwent stretching and working to achieve uniform thickness and flexibility. Tanners sometimes applied oils, particularly cod liver oil, to soften and preserve the material. Liquid tallow polishing prevented hardening. Finally, properly tanned leather was dried (occasionally smoked) and finished for use in boots, harnesses, shoes, and other everyday goods. The complete process from raw hide to usable leather often required many months and demanded specialized tools including various knives for dehairing and fleshing, workbenches, and tanner's benches.

Tannery work was physically demanding and hazardous. Handling heavy, waterlogged hides proved exhausting, while putrid odours from decomposing organic materials frequently caused workers to vomit or lose their appetites. High infection risks accompanied the trade, and omnipresent leather dust during hide finishing created respiratory problems. These conditions earned tanners the unflattering nickname "crotte de poule" (chicken droppings).

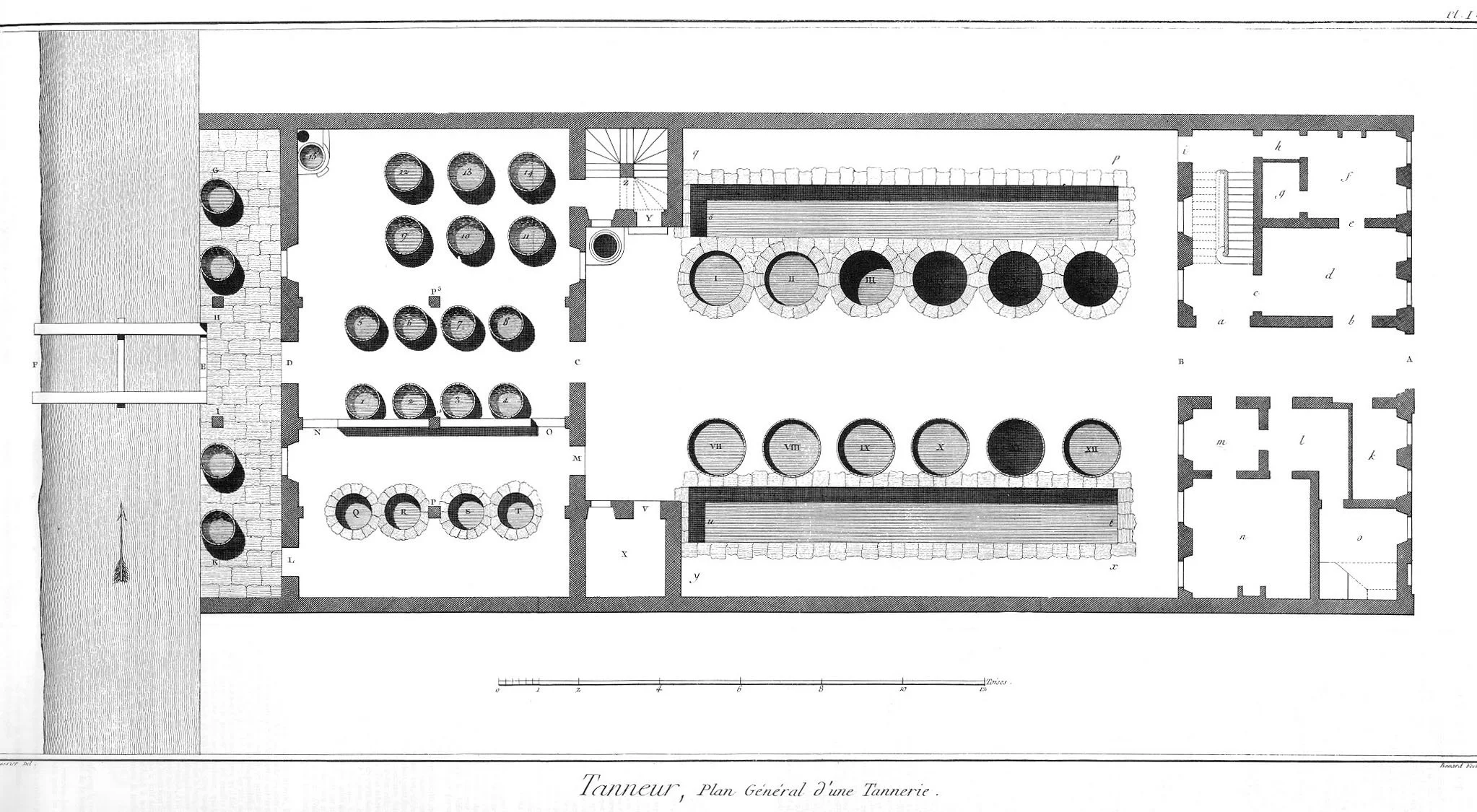

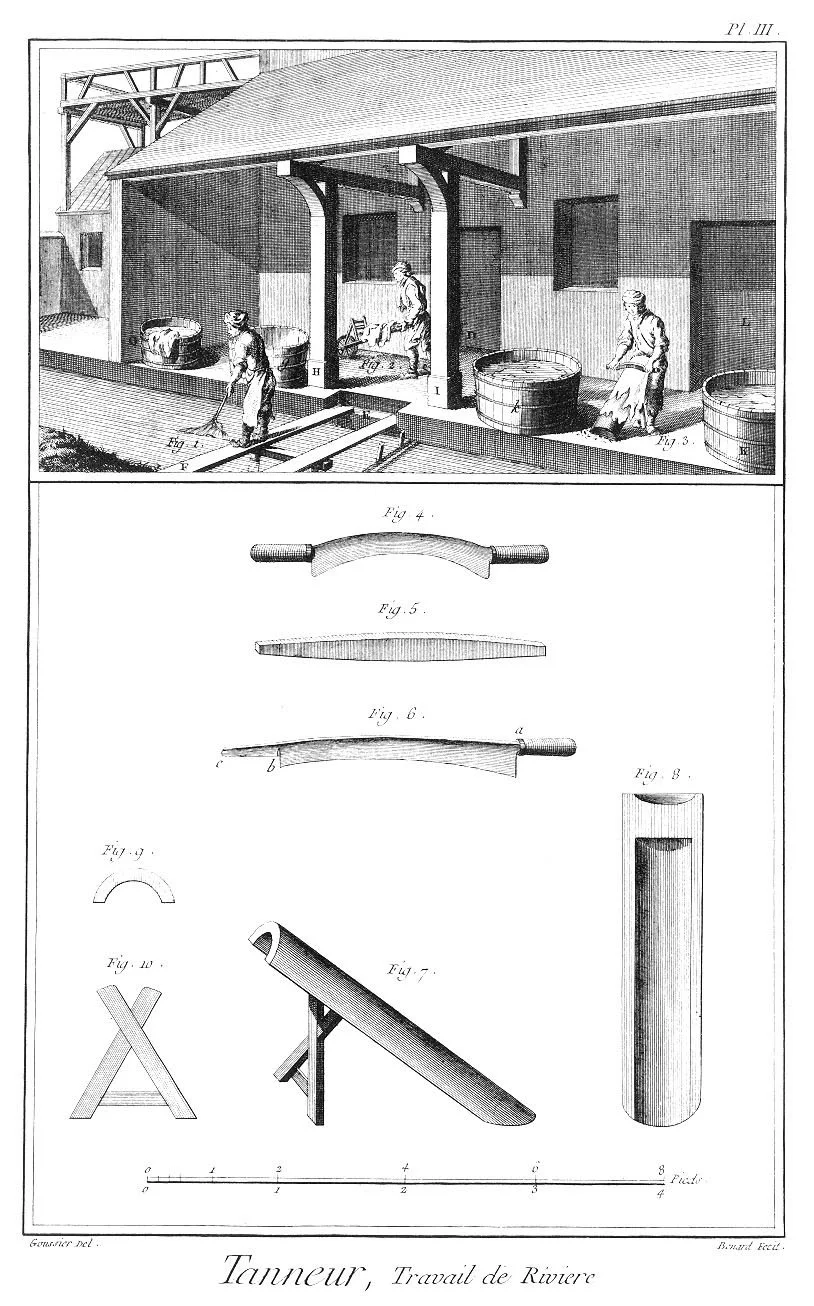

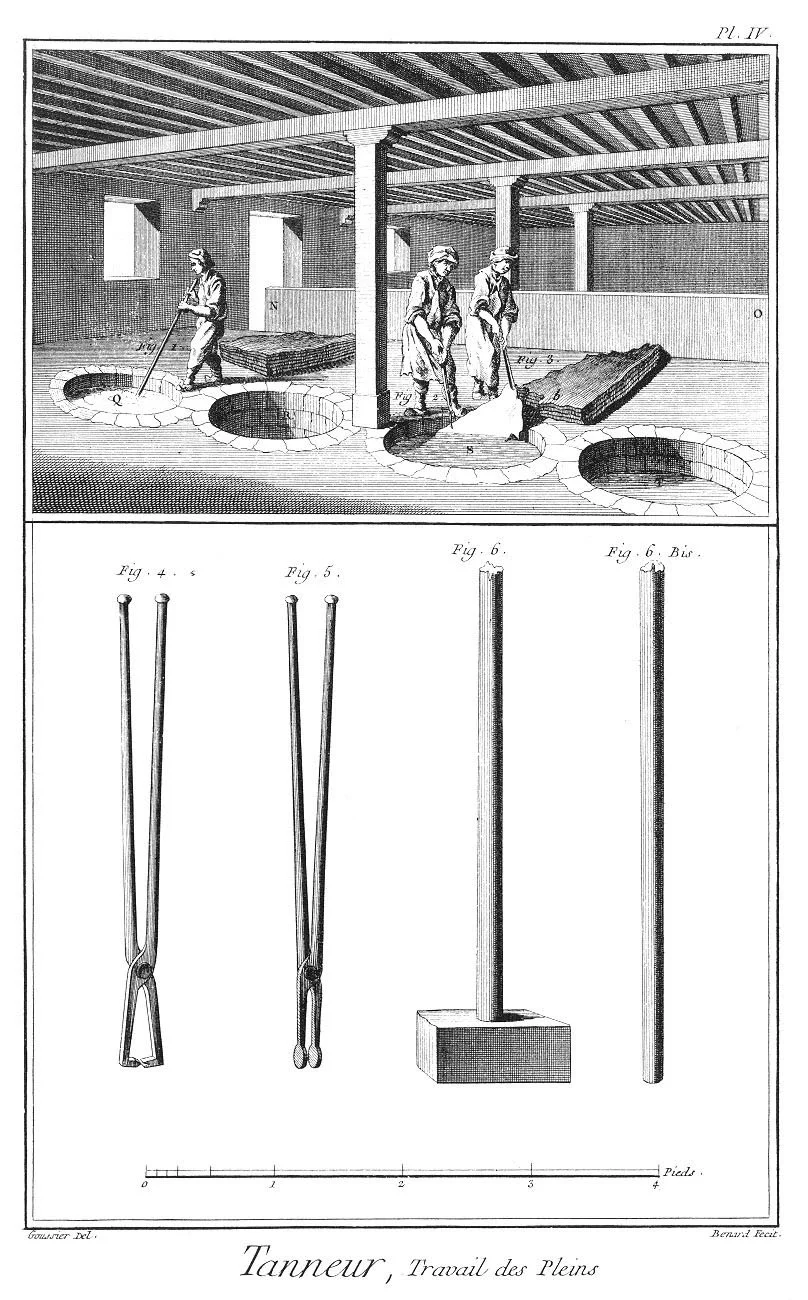

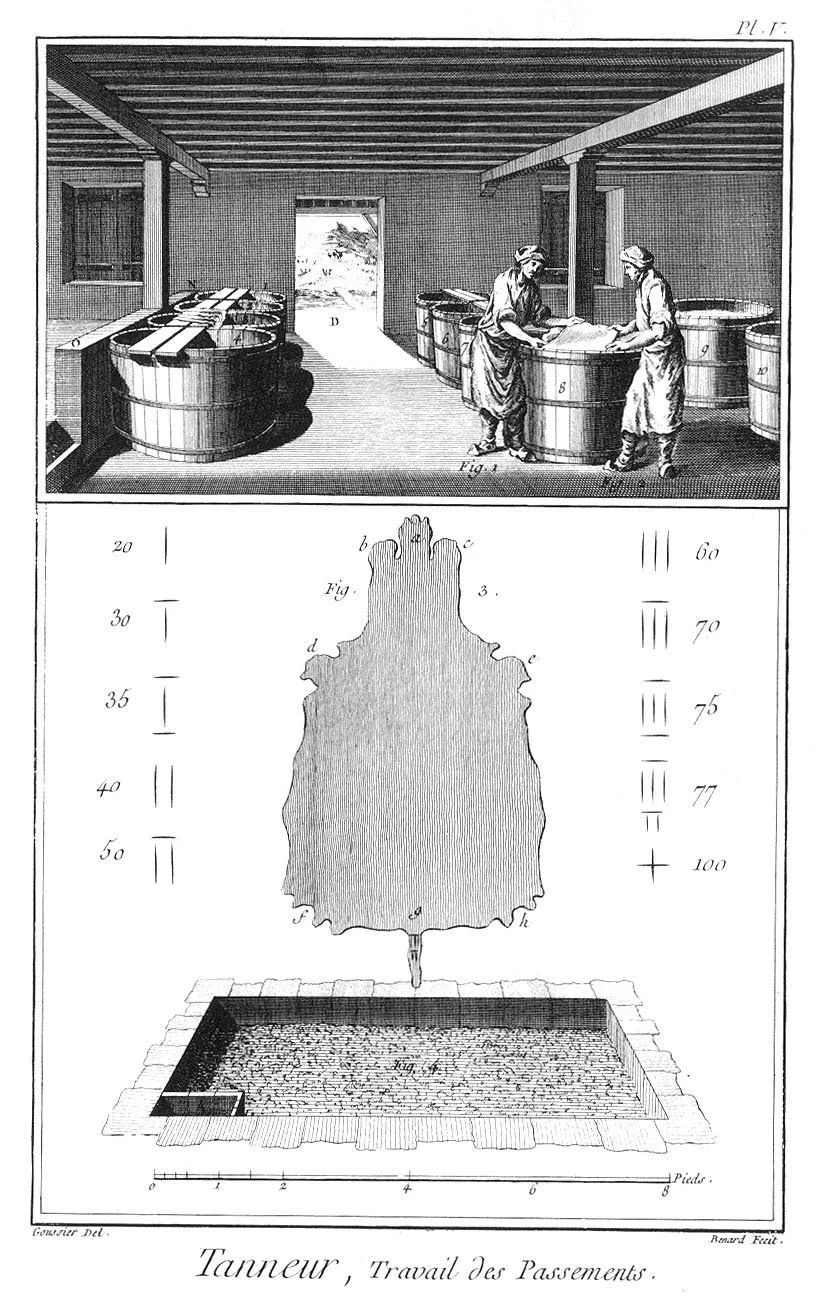

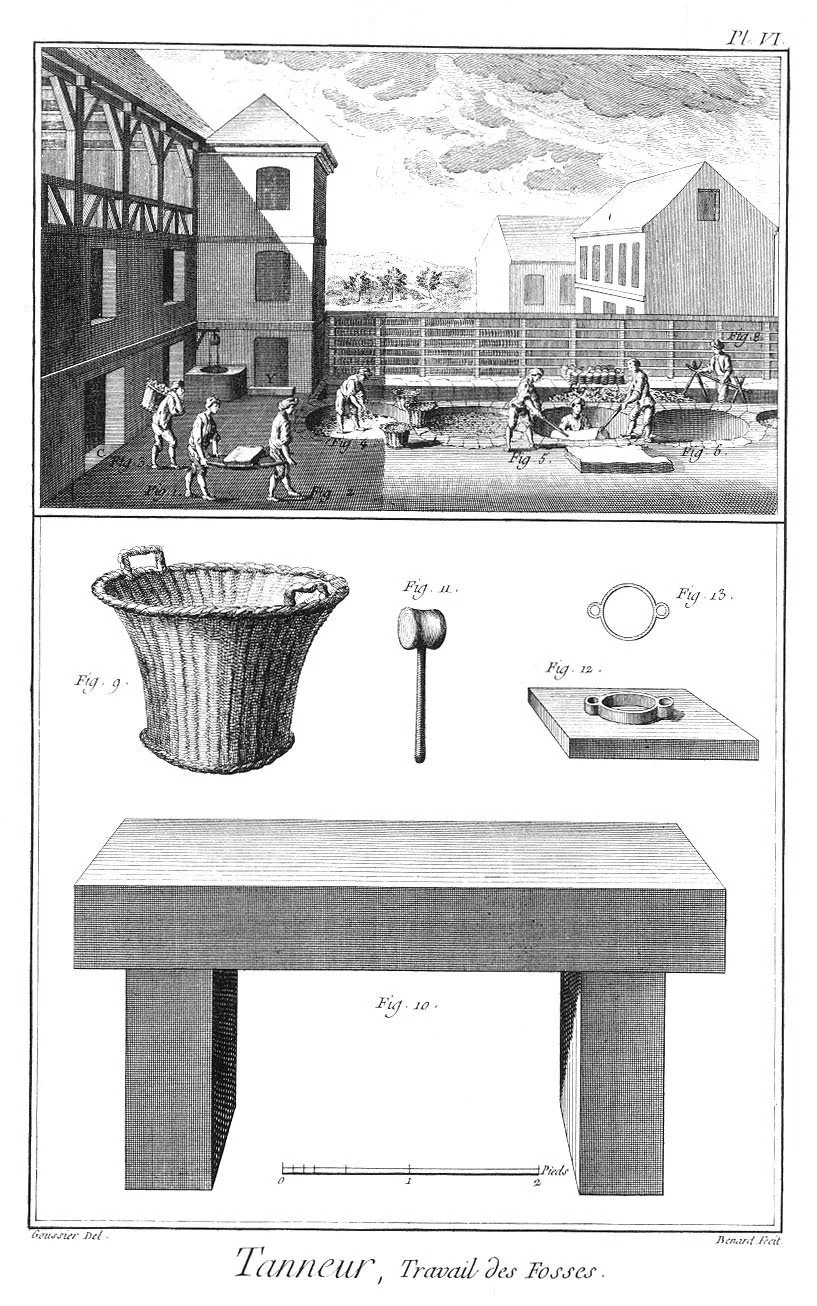

The tanning illustrations below from Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert's Encyclopédie provide invaluable documentation of 18th-century tanning techniques. These scholars aimed to record everyday trades and skilled crafts with unprecedented detail, creating visual records of tools, techniques, and working tannery scenes. Their plates offer rare insight into the precise methods used by colonial tanners—the scraping of hides, the operation of soaking vats, and the transformation of raw animal skins into the leather goods that every community required.

“General Plan of a Tannery”

“The tanner, river work”

“The tanner, pit work”

“The tanner, pit work (tan vat)”

“The tanner, passing work (acid liquor pit)”

Tannery Equipment and Tools

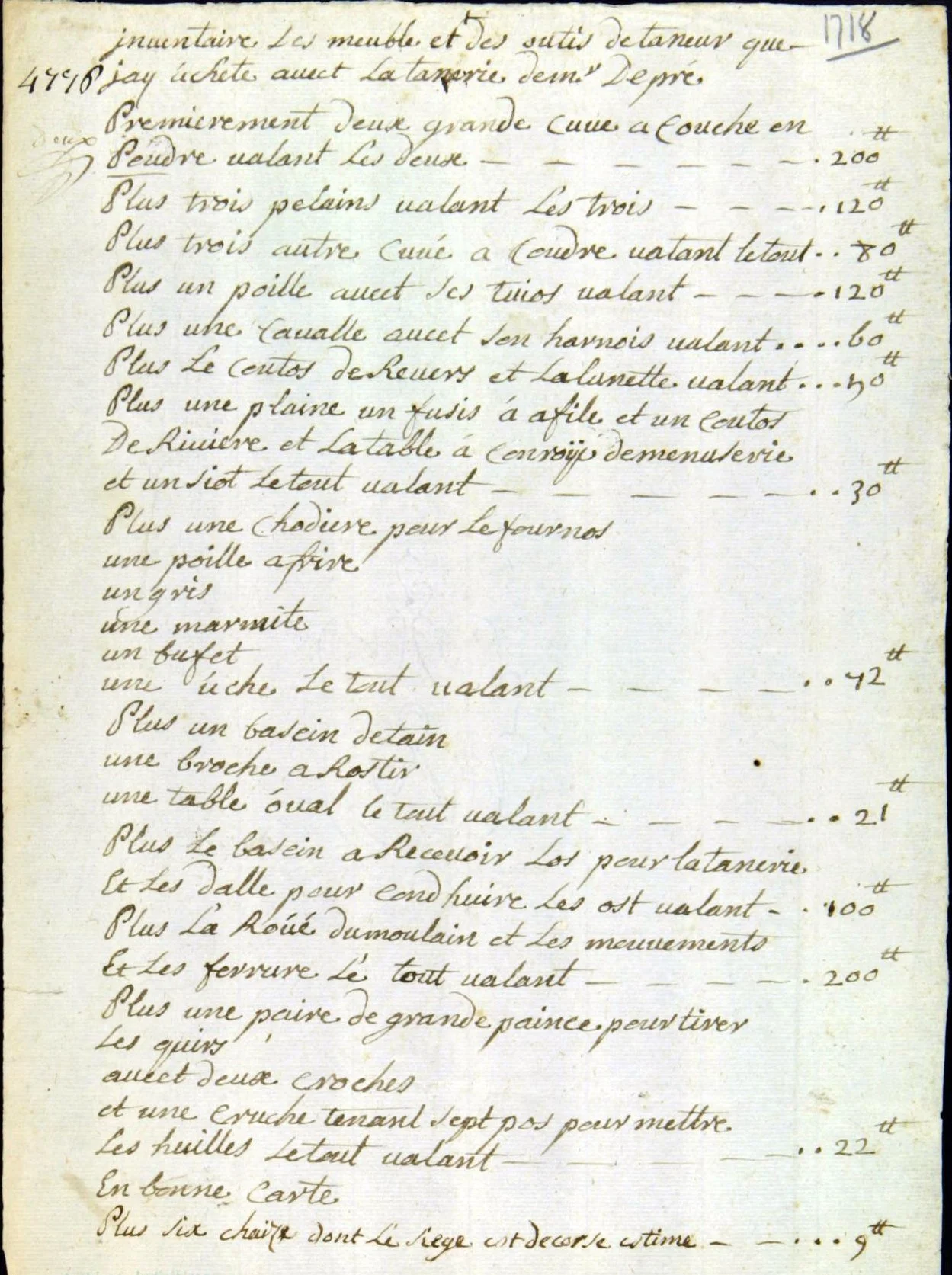

A circa 1720 inventory offers rare insight into the specialized equipment essential to colonial tanning operations. This detailed list, recorded by an unknown purchaser who acquired the furniture and tools of a tannery establishment (likely that of Joseph Guyon Després), documents a substantial investment of 1,084 livres—concrete evidence of the significant capital required to operate a functional tannery in New France. The comprehensive listing reveals both the specialized nature of the trade and its integration with domestic life:

Inventory of furniture and tanning tools that I purchased with Mr. Depré's tannery

First, two large soaking vats on stands, valued together at 200 livres

Plus three workbenches, valued together at 120 livres

Plus three other stitched vats, valued at 80 livres

Plus one stove with its pipes, valued at 120 livres

Plus one horse with its harness, valued at 60 livres

Plus the back-cutting knife and the half-moon knife, valued at 50 livres

Plus one bench with sharpening steels, a river knife, a joiner’s finishing table, and a small stool, all valued at 30 livres

Plus a boiler for the furnace, a frying pan, a grill, a cooking pot, a sideboard, and a chest, all valued at 72 livres

Plus a pewter basin, a roasting spit, and an oval table, all valued at 21 livres

Plus the basin to collect the water for the tannery and the runnels to carry off the water, valued at 100 livres

Plus the mill wheel, the gears, and the ironwork, all valued at 200 livres

Plus a pair of large pincers for pulling the hides, with two hooks, and a jug holding seven pots for storing oils, all valued at 22 livres

In good order

Plus six chairs with bark seats, estimated at 9 livres

The inventory demonstrates the substantial infrastructure required for professional tanning operations. The most expensive items—the soaking vats (200 livres) and mill machinery (200 livres)—represented core production equipment, while the inclusion of household furnishings reflects the typical integration of tanneries into family properties. The total investment of over 1,000 livres represented several years' wages for skilled colonial workers, illustrating both the capital-intensive nature of the trade and its economic importance in New France.

Tanner’s inventory, circa 1720 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Industrial Evolution

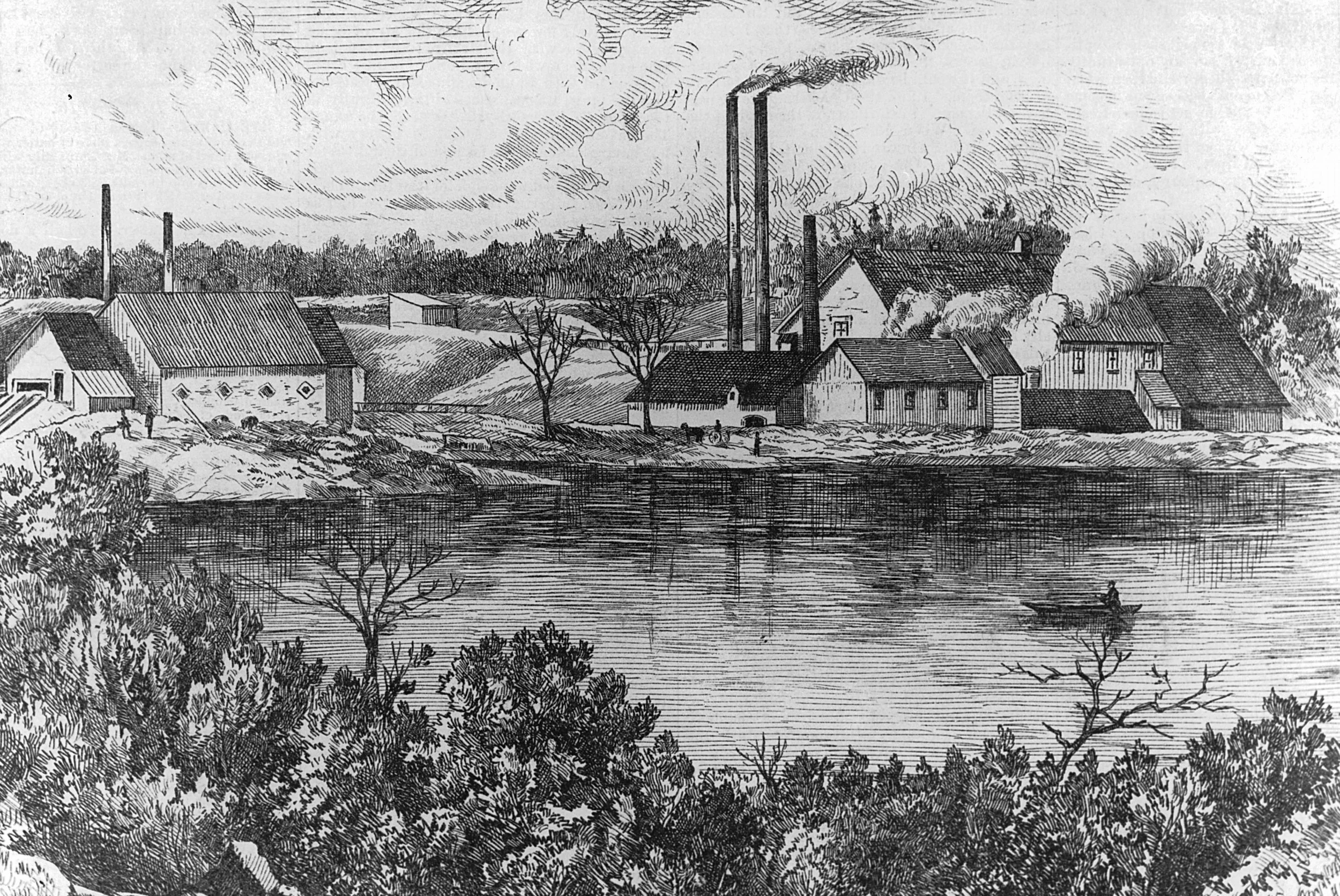

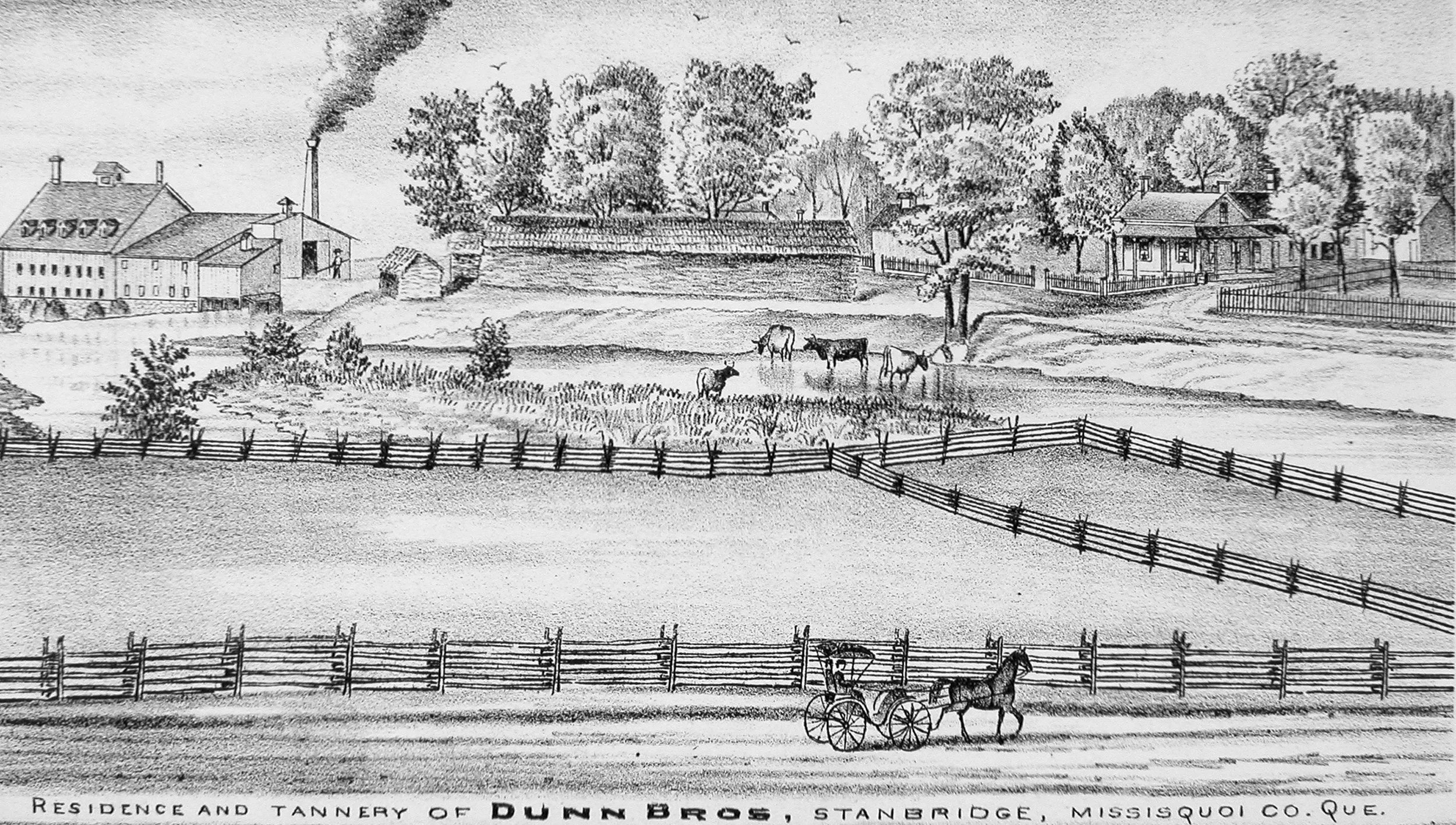

The tanning industry in Québec evolved dramatically from its artisanal New France origins to mechanized 20th-century operations. While colonial tanners worked individually or in small family enterprises using hand tools and natural materials, the Industrial Revolution transformed leather production into a larger-scale manufacturing sector. Steam-powered machinery replaced water wheels and manual labour, while chemical tanning agents—particularly chromium compounds introduced in American tanneries during the 1880s—accelerated processing. Québec's tanneries lagged behind this technological shift, not adopting chrome tanning until 1910, a delay that may have contributed to the decline of Québec's leather industry, which had previously been Canada's leading producer of leather goods. Despite technological advances, many Québec tanneries retained their traditional locations near waterways, maintaining geographic continuity with their colonial predecessors while adapting to serve Canada's growing demand for leather goods in an increasingly urbanized and industrialized society.

“J. L. Goodhue & Co., Tanners and manufacturers of leather belting and lace leather,” wood engraving by John Henry Walker, circa 1850-1885 (McCord Stewart Museum)

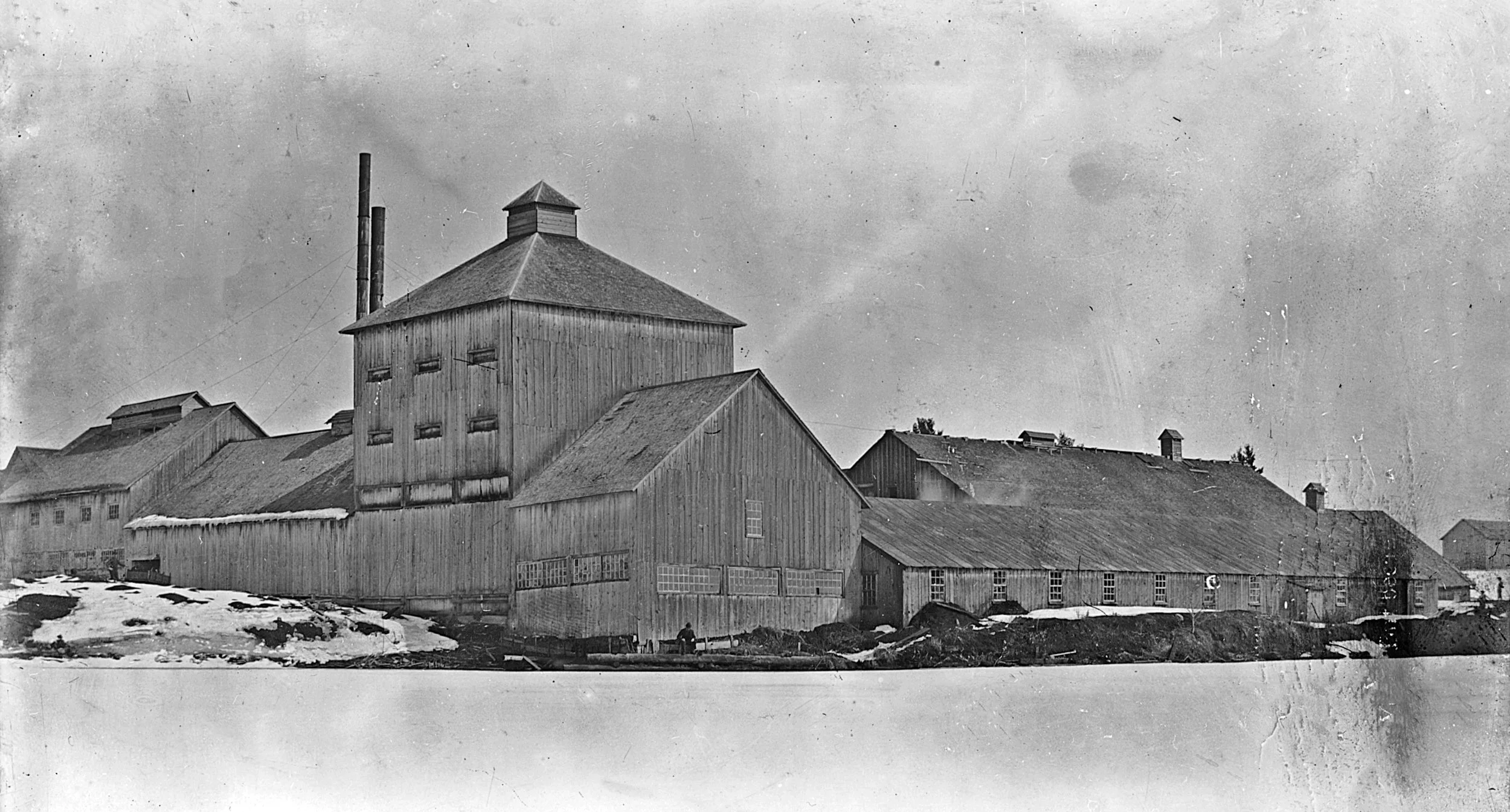

“Simpson Tannery and sawmill, Drummondville, QC, about 1875,” in Canadian Illustrated News (McCord Stewart Museum)

“Residence and tannery of Dunn Brothers, Stanbridge, Missisquoi County, Quebec,” 1881 (McCord Stewart Museum)

“Shaw & Cassil's Tannery, Drummondville, QC, about 1895,” photo by Charles Howard Millar (McCord Stewart Museum)

Raphaël Loiselle's tannery and shoe factory, circa 1920 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Indigenous Tanning Traditions

Long before European arrival, First Nations peoples had mastered animal skin tanning—essential for clothing, footwear, shelter, and rope production. Indigenous tanners primarily worked with deer, moose, elk, rabbit, buffalo, and bear hides, though each animal type served specific purposes. Different nations developed techniques adapted to local climate, animal species, and available materials. Northern peoples emphasized moose and caribou hides, while coastal and Arctic communities specialized in seal skin tanning.

Despite variation among nations, common elements characterized Indigenous tanning methods. After harvesting, hides were carefully removed in large pieces and soaked in water or wood ash solutions to loosen hair and flesh. Stretched over wooden beams or frames, hides were meticulously scraped with bone, stone, or metal tools to remove remaining meat, fat, and hair—work requiring strength and precision to avoid damage.

Hide scraper used by the Inuit and Thule people, circa 1000-1700 (McCord Stewart Museum)

Following initial cleaning, hides underwent stretching and working to ensure uniform thickness and prevent shrinkage. Treatment with fats or oils enhanced suppleness. "Brain tanning," a widespread method, employed the animal's own brain mixed with water to create a solution massaged into the hide. Natural oils and enzymes penetrated fibres, softening the leather. Treated hides required repeated stretching, pulling, and working until they dried soft rather than stiff.

Smoking typically concluded the process. Tanned skins suspended over smouldering fires absorbed smoke that coloured, preserved, and waterproofed the material while deterring insects. This labour-intensive process produced durable, soft leather suitable for clothing, footwear, bedding, and countless other applications, reflecting sustainable practices that utilized all animal parts through entirely natural, locally sourced materials.

"Félix Poitras dries his beaver pelts on a round frame in the Montagnais style," photo by Paul Provencher, circa 1942 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

As colonialism, modernization, and industrial goods have displaced many of these practices, there is now strong interest among Indigenous communities in reviving hide tanning, keeping elders’ knowledge alive, and restoring the full, historic process.

Here’s a rare look at J&FJ Baker, the only tannery in Britain still carrying on the ancient tradition of oak bark tanning.

This National Geographic Dangerous Jobs video follows a 17-year-old apprentice taking on one of the toughest—and foulest-smelling—trades in the world.

Individuals identified as tanners:

Michel Allard, François Aymé/Aimé dit Laprise, Michel André dit St-Michel, Sébastien Aubry, Alexis Ayotte, Jacques Baillet, Joseph [Barbançon?], François Barsalou, Gérard Barsalou, Jean Baptiste Barsalou, Isaac Beauchamp, Paul Beauchamp, Didace Beaupré, Pierre [Bedagaray?], Jacques Bédard, Joseph Belleau dit Larose, Nicolas Blanchard, Louis Bluteau, Nathaniel Boulter, Michel Bousquet, Alexis Bouthillier, Basile Brault dit Pomminville, Joseph Bouvet, Étienne Brunet, Jean Baptiste Bussière, Joseph Chalifour, Pierre Chamereau dit St-Vincent, François Chapleau, Étienne Charest, Étienne Charest (fils), Charles Charpentier, Pierre Chazal, Louis Chevalier, Pierre Chezal, Paul Collette, Jean Baptiste David, Jean Baptiste de Dieu, François Debigare, Jean Marie Deguise dit Flamand, Joseph Deguise dit Flamand, Charles Delaunay, Jacques Delaveau/Laveau, Joseph Destroismaisons dit Picard, Jacques Drolet, Dominique [Dubroca?], Pierre Ducep dit Lafleur, François Dulaurent, Germain [Estivalet?], Richard Freeman, Zacharie Gagnon, Jacques Gaudry, Jean Elie Gauthier, Louis Gauthier, Alexis Gauvreau, Claude Gauvreau, Étienne Gauvreau, François Gauvreau, Louis Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau, Pierre Gendron, Charles Giroux, Jean Marie Giroux, Noël Giroux, François Goyette, Joseph Guyon dit Després, Jean Baptiste Hallé, Pierre Hay/Haya/Haye, René Hautbois, Thomas Huguet, Antoine Huppé dit Lagroix, Claude Hurel, Jacques Jahan dit Laviolette, Antoine Joron, Michel Lambert, Paul Lamothe dit Cauchon, Charles Larche, Jean-Baptiste Larchevêque dit Grandpré, Augustin Laurent dit Lorty, Jean Laurent dit Lorty, Benjamin Lauzon, Joseph Lavigne, Antoine Leblanc, Charles Lefebvre, Charles Lemieux, Octave Lemieux, Claude Lenoir dit Roland, Gabriel Roland dit Roland, Joseph Lenoir dit Roland, Nicolas Roland dit Roland, Laurent Loraine dit Lagiroflée, Louis Mallet, Louis Manseau, Jean Baptiste Maranda, Jean Moreau, Jean Mouchère dit Desmoulins, Louis Régis Morin, Guillaume Nantel, Joseph Normand, Charles Paquet, François Patry, Pascal Persillier dit Lachapelle, George Phillip, Joseph Pigeon, Jean Louis Plessis dit Bélair, Léon Plessis dit Bélair, Raymond Plessis dit Bélair, Charles Poliquin, Joachim Primeau, Paul Primeau, Pierre Robreau dit Duplessis, Joseph Roberge, Amable Robert dit Lamouche, Pierre Robitaille, Jacques Rochon, Joseph Rochon, Charles Roy, Jean Baptiste Hippolyte Sarrazin, John Selby, William Smith, Hippolyte Thibierge, Jean Thomelet, Pierre Thomelet, François Valiquet, Narcisse Vincent, John Watson, Asa Willett, and many others.

Individuals identified as master tanners:

Joseph Allard, Jacques Baillet, Louis Barré, Gérard Barsalou, Jean Baptiste Bizet, Louis Bluteau, Michel Boivin, Antoine Boudrias, Louis Boudrias, Alexis Bouthillier, Noël Breux, Jean Baptiste Cadot, Gilles Campeau, Pierre Chamereau dit St-Vincent, Jean Baptiste Courcelles, Gabriel Crevier, Pierre Cuisson, Louis Dagenais, Pierre Abraham de Courville, Louis Daguerre dit Marechal, Baptiste Denis, Jean Louis Décary, Urbain Décary, Brewer Dodge, Isaac Dugas, Joseph Durand, Nicolas Durand dit Desmarchais, Pierre Durand dit Desmarchais, Pierre Duroy, Gabriel Ethier, Noël Favreau, Joseph Fissiau, Jean Baptiste Flibotte, Benjamin Forbes, Robert Farrell, Casimir Fortier, Zacharie Gagnon, Pierre Gariépy, Claude Gauvreau, Étienne Gauvreau, François Gauvreau, Louis Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau, Jean Marie Giroux, Noël Giroux, Pierre Giroux, Jacques Goguet, Pierre Henrichon, Claude Hurel, Michel Houle, Thomas Huguet, Antoine Huppé dit Lagroix, Joseph Henri dit Jarry, Louis Henry dit Jarry, David Jenkins, Jean Baptiste Lacombe, Pierre Lacombe, Benjamin Lauzon, François Lauzon, Julien Leblanc, Antoine Leduc, Pierre Leduc, Germain Lefebvre, Jean Lefebvre, Charles Lenoir dit Rolland, Jean Baptiste Lenoir dit Rolland, Joseph Lenoir dit Rolland, Vital Mallet, Jean Baptiste Maranda, Charles Marquette, Jean Marcel Moreau, Hyacinthe Ouellet, Pierre Benjamin Papin dit Baronet, Pascal Parsillé dit Lachapelle, Jean Baptiste Picard, Basile Pigeon, Basile Gabriel Plessis dit Bélair, Jean Louis Plessis dit Bélair, Pierre Plessis dit Bélair, Raymond Plessis dit Bélair, Pierre André Ponton dit St-Germain, Joachim Primeau, Jean Baptiste Robert, Joseph Rochon, Nicolas Sarrazin, Robert Smith, Jean Baptiste St-Denis, Jean Baptiste Tessier dit Lavigne, Louis Tondreau, Jean Toupin, Louis Travé dit St-Romain, Jean Baptiste Turcot, Laurent Turcot, Raymond Vair dit Raymond, Guillaume Valade, François Valiquet, Joseph Valiquet, Louis Valiquet, Pierre Valiquet, John Watson, and many others.

Sources:

Régis de Roquefeuil, “BYSSOT (Bissot) DE LA RIVIÈRE, FRANÇOIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, Université Laval/University of Toronto, 2003– , (https://www.biographi.ca/fr/bio/byssot_de_la_riviere_francois_1F.html : accessed 11 Sep 2025).

André Vachon, “TALON (Talon Du Quesnoy), JEAN ,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/talon_jean_1E.html : accessed 11 Sep 2025).

Frances Kelley, "Industrie de la chaussure," in l'Encyclopédie Canadienne, Historica Canada (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/fr/article/chaussure-industrie-de-la : accessed 11 Sep 2025), 16 Dec 2013.

“Tannerie artisanale de la rue De Saint-Vallier,” Patrimoine : L’archéologie à Québec, Ville de Québec (https://archeologie.ville.quebec.qc.ca/sites/tannerie-artisanale-de-la-rue-de-saint-vallier/histoire-d-une-tannerie-artisanale-de-la-rue-de-saint-vallier/ : accessed 11 Sep 2025).

"Histoire de Saint-Henri," Société historique de Saint-Henri (https://www.saint-henri.com/histoire/ : accessed 20 Sep 2025).

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-BSFV-G?cat=541271&i=132&lang=en : accessed 5 Sep 2025), Contract for tanning seal skins between Toussaint Lefranc, merchant, of the town of Villemarie, acting on behalf of François Hazeur, advisor to the King on the Sovereign Council, and Gérard Barsalou, tanner, of the town of Villemarie, 11 Nov 1704, images 133-134 of 2850; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Olivier Paré, "Gabriel Lenoir dit Rolland," Encyclopédie du MEM (https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/memoiresdesmontrealais/gabriel-lenoir-dit-rolland : accessed 20 Sep 2025).

Ange Pasquini, "La tannerie des Bélair (1714-fin XVIIIe)," Blogue : "La petite histoire du Plateau" (https://blogue.histoireplateau.org/2024/02/20/tannerie-des-belair/ : accessed 20 Sep 2025).

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTH-57S6-T?cat=541271&i=2986&lang=en : accessed 5 Sep 2025), Contract for the sale of ox, cow and calf hides between Claude Robillard, butcher, and Jacques Baillet, tanner, 9 May 1695, image 2987 of 3065; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Philippe Fournier, La Nouvelle-France au fil des édits (Septentrion, Québec : 2011).

Jeanne Pomerleau, Arts et métiers de nos ancêtres : 1650-1950 (Montréal, Québec: Guérin, 1994), 411-416.

Marise Thivierge and Nicole Thivierge, "Leatherworking," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/leatherworking : accessed 20 Sep 2025). Article published 7 Feb 2006; last edited 6 Dec 2016.

"Tanneur," in Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers digitized by the University of Michigan Library (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/did/did2222.0001.613/--tanner : accessed 11 Sep 2025).

“Fonds Juridiction royale de Montréal - Archives nationales à Montréal," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/700639 : accessed 21 sep 2025), "Inventaire d'un achat de meubles et d'outils de tanneur appartenant à [Joseph Guyon Després?]," circa 1720, reference TL4,S1,D2589, Id 700639.

"A Quick History Of The Leather Tanning Industry," Blackstock Leather (https://blackstockleather.com/history-of-the-leather-tanning-industry/ : accessed September 21, 2025).

“Moosehide Tanning,” Indigenous Yukon (https://indigenousyukon.ca/art-to-explore/learn-about-our-art/moosehide-tanning : accessed 11 Sep 2025).

Katie Crane and Dale Gilbert Jarvis, “The History and Practice of Bark Tanning in Newfoundland and Labrador,” Heritage NL (https://heritagenl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/007-History-and-Practice-of-Bark-Tanning-in-NL.pdf : accessed 20 Sep 2025).

“Native American Braintanning at the Time of Contact,” Traditional Tanners (https://braintan.com/articles/brainboneshotsprings.html : accessed 20 Sep 2025).

“Tanning Hides,” Native Art in Canada (https://www.native-art-in-canada.com/tanninghides.html : accessed 20 Sep 2025).

Julia Prinselaar, “Tanning Hides as an Act of Reconciliation,” Northern Wilds (https://northernwilds.com/tanning-hides-act-reconciliation/ : accessed 20 Sep 2025).