Lumberjack

Was your ancestor a "bûcheron", or lumberjack? Learn about this very Canadian occupation, past and present.

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Le Bûcheron | The Lumberjack

"Le bûcheron", painting by Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (BAnQ numérique).

A bûcheron, or lumberjack, was a man who cut down trees in a forest using hand tools such as axes or saws. The logs would then be transported with the ultimate goal of turning them into wood products. Lumberjacks were also called “woodcutters” and “shanty boys” in English, and “bûcheux” in French.

Though men were felling trees from the early days of New France, it was a normal part of life as opposed to a traditional occupation. Burning wood was the only way to stay warm during the winter, so men and boys were used to chopping down trees and cutting them into manageable pieces. Wood was also the primary building material for dwellings, and trees needed to be cut down to clear the way for agriculture. Most villages had a sawmill. And even before the days of New France, Indigenous peoples had been felling trees with stone axes for hundreds of years, if not more.

Logging truly came into its own as an industry around the turn of the 18th century. A few decades later, the term “lumberjack” was coined. For the next 100 years, logging boomed in Eastern Canada, where white pine was the tree of choice. In the early 19th century, the industry was primarily fuelled by Britain’s shipbuilding and railroad needs. The Ottawa region in particular was a prime location for pine trees, and logging camps sprung up all along the Ottawa River. For the first time, the lumber industry became more important than the fur trade. Then, U.S. demand for pine planks took precedence and wood products were sent south of the border instead of the UK.

As white pine forests were being depleted in the East, the lumber industry began to shift West, particularly to British Columbia. There, the massive Douglas fir was king.

“It was estimated that during the 19th century, which was the heyday of the white pine era, half the males in Canada were employed as lumberjacks.”

Lumberjack camp at Lac Vlimeux, Québec, circa 1895. Photo by Fred C. Würtele (BAnQ numérique).

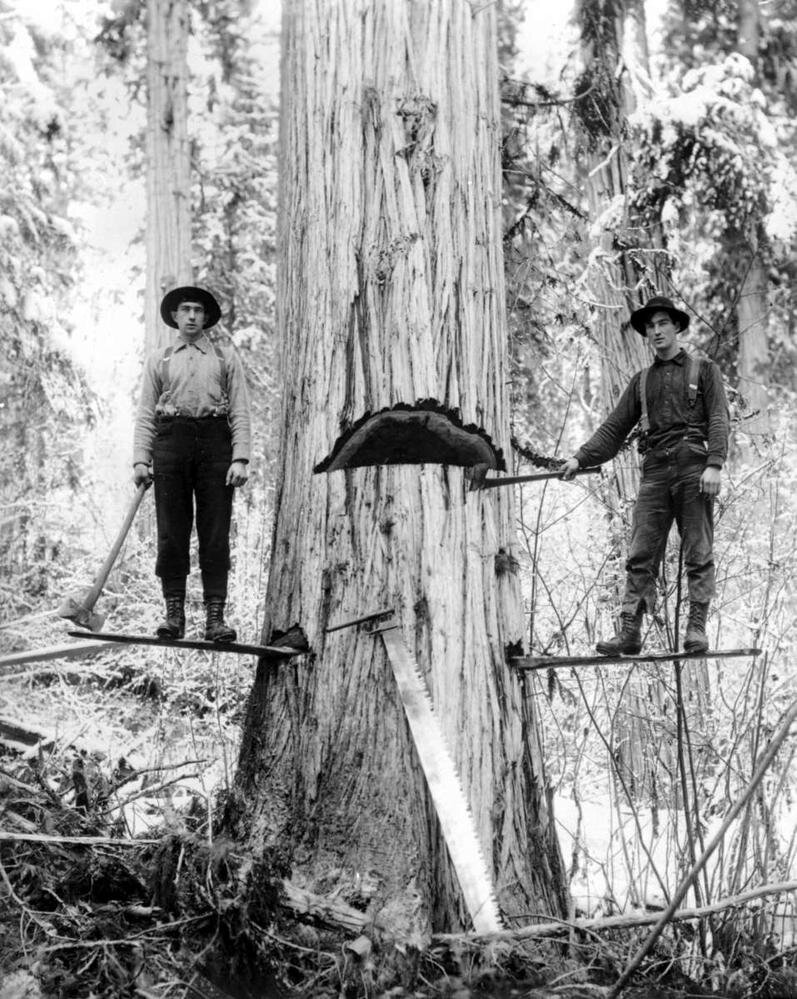

Adams River Lumber Company loggers at Chase, BC, circa 1920 (Royal BC Museum).

Logging normally took place during the winter months, as it was easier to cut down trees when their sap wasn’t flowing. Cold weather also allowed for logs to be more easier hauled over snow to the nearest frozen river by horses. In early spring, the logs were collected and transported on rivers by log drivers (some lumberjacks did both these jobs). This meant that logging was a seasonal job; during the rest of the year, most lumberjacks worked in farming and agriculture, or hunted. Then, in late autumn, they returned to build their logging camps and clear roads in preparation for the winter.

Working conditions were brutal: dawn til dusk, six days per week. Trees were normally cut down by a team of two men using axes. They worked face to face, striking the trunk with an ax about two feet (60cm) above the ground. When the opposing cuts met, the tree fell. In the 19th century, the godendard was used, a two-handled two-man saw measuring two metres. It was later replaced by the sciotte, a smaller and more manageable saw.

Lumberjacks also had to stack the logs as they went along, having strict quotas to meet. At the Spring Crique camp near Saint-Michel-des-Saints in the 1920s, for example, each team of five men was required to produce 300 logs per day.

Working as a lumberjack was extremely dangerous. Getting hit by a falling tree or being injured with an axe or a saw was not uncommon. After a long day of work, he retired to the tiny, smelly, ramshackle, flea-infested cabin he shared with other lumberjacks. Hygiene was seriously lacking.

Booth Lumber Camp at Aylen Lake, Ontario, circa 1895 (Library and Archives Canada).

Lumberjacks needed to eat an enormous amount of food to keep them going. Life in the logging camps (or “shanties”, as they were called) was strictly regulated; some companies even prohibited talking during meals. Some set incredibly short time periods in which the men could eat; most prohibited alcohol. Most men were also far from their families. Given that the lumberjacks didn’t work on Sundays, Saturday nights were normally spent telling stories, playing music and dancing.

Needless to say, when the lumberjacks were heading to a camp, or heading home, they celebrated with zeal, as the below newspaper article suggests. Unfortunately this zeal often meant that lumberjacks spent their earnings very quickly.

Article excerpt from The Gazette (Montreal), 2 Jan 1948

Headline in the The Gazette (Montreal), 26 May 1924

An ad for “lumberjacks” in The Province (Vancouver), 27 Aug 1926

By the mid-1930s, motorized chain saws were being developed in Germany and the United States. Models were improved and redesigned specifically for the logging industry. Within a decade, chainsaws began to replace axes and manual saws in Canada, changing the industry dramatically. Skidders replaced horses, and transport trucks replaced the log drive on the river. Productivity greatly improved, requiring less work force. Lumberjacks still exist today, though they are called loggers. Gone are the days of ramshackle, flea-infested camps. Most loggers today simply commute from their home to the forest.

Lumberjacks still hold a significant place in Canadian folklore. With their heroic strength, masculinity and popular storytelling, they remain iconic figures. Lumberjack folk heroes include American Paul Bunyan and French-Canadian Joseph Montferrand, aka “Big Joe Mufferaw”. (See the History of Mattawa tor read more about Big Joe).

In recent years, the lumberjack has even influenced men’s fashion. Beards, messy hair and plaid shirts all made a significant comeback.

"The Canadian Lumberman", illustration in Canadian Forest Industries 1905-1906 (Wikipedia Commons).

"The Canadian Lumberman", illustration in Canadian Forest Industries 1911 (Wikipedia Commons)

Sources and additional reading:

Thomas Bardin, “Les métiers forestiers d’autrefois : de bûcheron à garde forestier en passant par « cageux », Société d’histoire forestière du Québec (https://shfq.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/metiers-forestiers-autrefois-TB.pdf)

Raymonde Beaudoin, “La vie dans les camps de bûcherons au temps de la pitoune”, Histoire Canada (https://www.histoirecanada.ca/consulter/entreprises-et-industrie/la-vie-dans-les-camps-de-bucherons-au-temps-de-la-pitoune), article published November 13, 2019.

Jensen Edwards, “Cutting down the Kaiser: How Canadian lumberjacks helped win the First World War”, Boundary Creek Times (https://www.boundarycreektimes.com/news/cutting-down-the-kaiser-how-canadian-lumberjacks-helped-win-the-first-world-war/), article published November 6, 2019.

Mark Kuhlberg, "Lumberjacks", In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lumberjacks), article published May 06, 2014.

Jim Wardrop, “British Columbia's Experience with Early Chain Saws”, Material Culture Review, 2 (https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/16942/23057), published 6 Jun 1976.

Association forestière des deux rives, “Bûcheron, un métier du passé” (https://www.touchedubois.org/bucheron).