Louis Hébert & Marie Rollet

Learn the story of Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet, the first permanent French settler family in Québec. Follow Hébert’s early voyages to Acadia, his work as an apothecary and farmer, and the family’s pivotal role in the development of New France. This biography explores their arrival in 1617, their contributions to the colony, and the enduring legacy they left through their descendants.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Louis Hébert & Marie Rollet

The First Settler Family of Québec

Louis Hébert, son of Nicolas Hébert and Jacqueline Pageot (also spelled Pajot), was born around 1575 in Paris, France. His father was an apothicaire, or apothecary. His mother was the daughter of the Paris bourgeois Simon Pageot and Jeanne Guerineau, and had been widowed twice before marrying Nicolas. Louis had three known siblings: Charlotte, Jacques, and Marie. His mother died around 1579, when he was only four or five years old. He was first raised by his older sister Charlotte and later by his stepmother, Marie Auvry.

Rue Saint-Honoré on "Le plan de la ville, cité, université fauxbourg de Paris" (Map of the city, town, university, suburbs of Paris), Derveaux & Tavernier, 1615 (Wikimedia Commons)

Louis grew up in a house known as the “Mortier d’Or,” located at 129 rue Saint-Honoré, near the Louvre, which was then the royal palace. The property, purchased by the Hébert family in 1572, served both as a residence and as a working apothecary. It was a substantial stone building made up of two conjoined structures, three storeys high, containing nine rooms. The ground floor opened onto the street with two boutiques, and a vaulted passageway provided access to the upper floors and an interior courtyard. The property also included extensive workspaces essential to apothecary practice, an attic for storing medicinal plants, and a small laboratory. Life in this bustling commercial quarter placed the family at the heart of Parisian economic and political tensions.

Louis’s father, Nicolas, managed several properties on rue Saint-Honoré, though none of them belonged to him. Most of the properties came from the estate of Jacqueline’s second husband and were intended for her children. During the Wars of Religion, Paris endured a brutal siege (1589–1590) that severely disrupted commerce. Nicolas was forced to take on loans and was eventually imprisoned for two years for unpaid debts. After his release and subsequent death in 1600, Louis’s prospects in Paris were limited. He even ceded his share of the Mortier d’Or house to his half-sister Renaude Maheut to settle family obligations.

Paris, controlled at the time by the Catholic League, endured famine, disease, and intense violence during the siege of 1590. Henry IV’s forces encircled the city from May to September 1590, cutting off supply routes and preventing food from entering the capital. As starvation deepened, residents resorted to eating horses, dogs, rats, and even roots and grass; contemporary chroniclers reported that thousands died of hunger and illness. Daily life was marked by fear and disorder: skirmishes erupted near the barricades, reprisals and executions were carried out by both factions, and bodies accumulated in public areas. Living on rue Saint-Honoré, the Hébert family would have been directly exposed to this suffering—witnessing empty markets, famine deaths, and violent encounters in nearby streets. Such extreme instability may have later influenced young Louis to seek a more secure future elsewhere.

"Procession of the League on Place de Grève," unknown artist, 1590 (Wikimedia Commons)

This painting represents a politicized religious procession staged by the Catholic League in the Place de Grève during the French Wars of Religion. It shows clergy, militants, and citizens participating in a public display of religious fervour that doubled as a demonstration of political power in a Paris controlled by the League. Such events played a crucial role in shaping political outcomes, as the Catholic League used public religious spectacle to mobilize crowds and assert authority during this turbulent period.

Despite these early hardships, Louis followed in his father’s footsteps and trained as an apothecary. He attended school, where he learned to read and write in both French and Latin, and then spent five years apprenticed to master apothecaries. During this training, he studied the medicinal uses of herbs, plants, and roots and learned how to prepare remedies from them. In 1603, he qualified as a maître-apothicaire, or master apothecary.

The master apothecary and his apprentice in the laboratory, artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (November 2025)

Marie Rollet

Location of Sedan in France (Mapcarta)

Marie Rollet, daughter of Jean Rollet and Anne Cogu, was baptized on November 7, 1577, at the Huguenot Temple in Sedan, Champagne, France. Her godparents were Pierre Berger and Marie L’Huillier. [The original baptism record no longer exists, as many records were destroyed during a 1940 bombardment.] Marie’s father was a canonnier du roi, or king’s gunner, and also served as a soldier and castle gatekeeper. She had four known siblings: Pierre, Marthe, Perrete, and Claude. [Marie’s name was also spelled Rolet and Raullet.]

Marie received a religious education at a convent, where she learned to read and write—suggesting that her family may have sent her to a Catholic institution despite their Protestant background.

Sedan Castle (photo by MOSSOT, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Located in the present-day department of Ardennes, Sedan lies just ten kilometres from the Belgian border. Today, it has approximately 17,000 residents, known as Sedanais and Sedanaises.

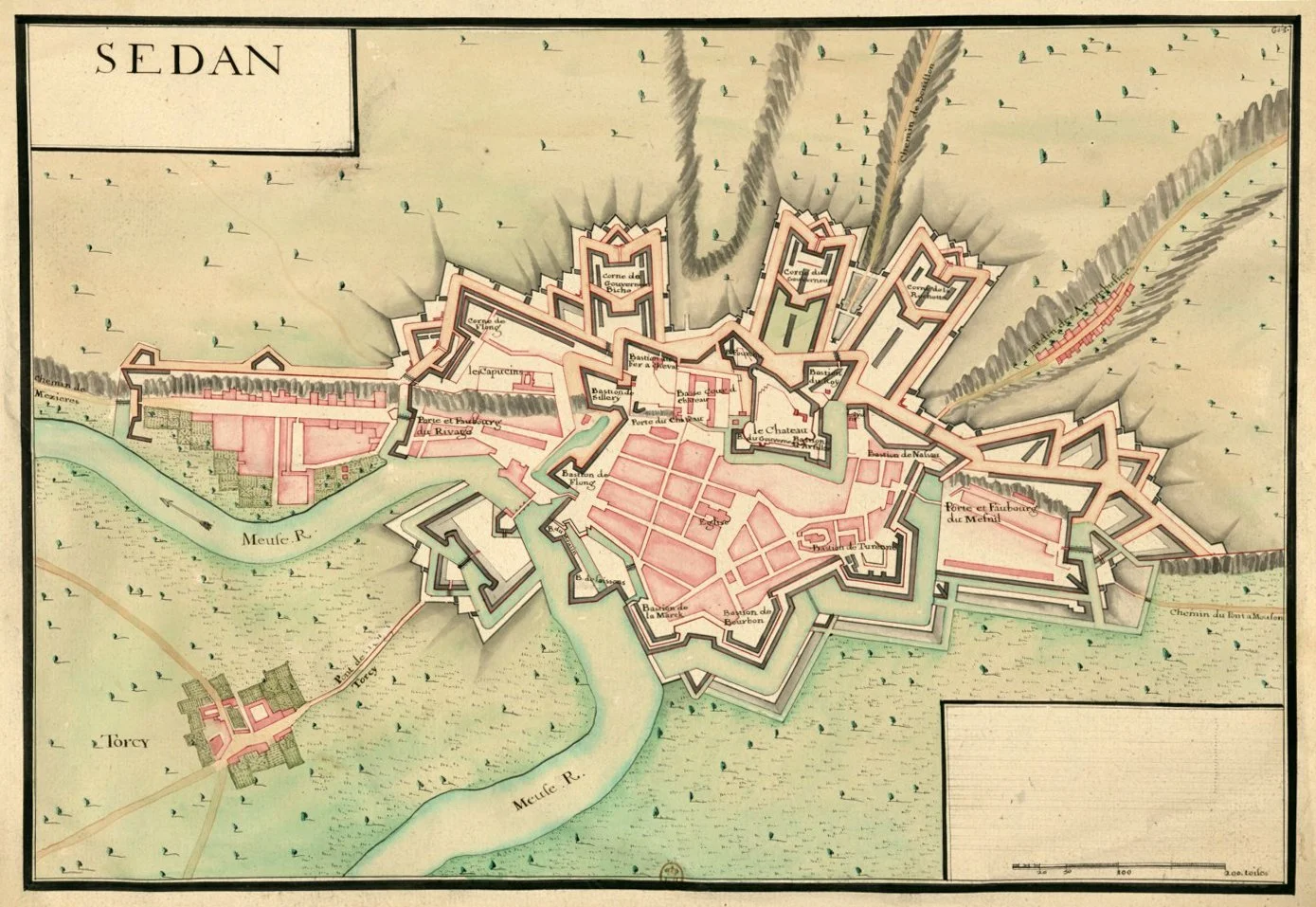

Map of Sedan, circa 1695–1713 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Postcard of Sedan, 1912 (Geneanet)

Life in Protestant Sedan

At the time of Marie’s baptism in 1577, Sedan was an independent Protestant principality ruled by the La Marck family. After embracing Calvinism in the early 1560s, the rulers transformed it into a refuge for Huguenots fleeing the Wars of Religion. Contemporary observers even referred to Sedan as a “little Geneva,” noting its fortified layout, Protestant princes, and a dense Reformed community strengthened by refugee artisans who helped expand local textile industries. By the late 1570s, the principality was investing heavily in Calvinist education: a Reformed college was founded in 1579 at the initiative of Françoise de Bourbon, later recognized by the national synod as the Academy of Sedan—one of the major centres for training Reformed pastors. Within the town, Protestant worship, schooling, and civic life were formally organized and relatively secure, even as much of France remained embroiled in civil war.

By the turn of the century, the broader religious landscape had shifted. The Edict of Nantes (1598) ended the main phase of the Wars of Religion and granted Huguenots limited freedom of conscience, certain designated places of worship, and civil rights. It nevertheless prohibited Protestant public worship within Paris itself.

Marie married the merchant François Dufeu sometime before 1601. The couple lived for a time in Compiègne, roughly halfway between Sedan and Paris. They had no known surviving children, and at some point—though the details remain unclear—Marie moved to Paris as a widow.

Marriage of Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet

Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet were married on February 19, 1601, in the parish of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. He was approximately 26 years old; she was 23.

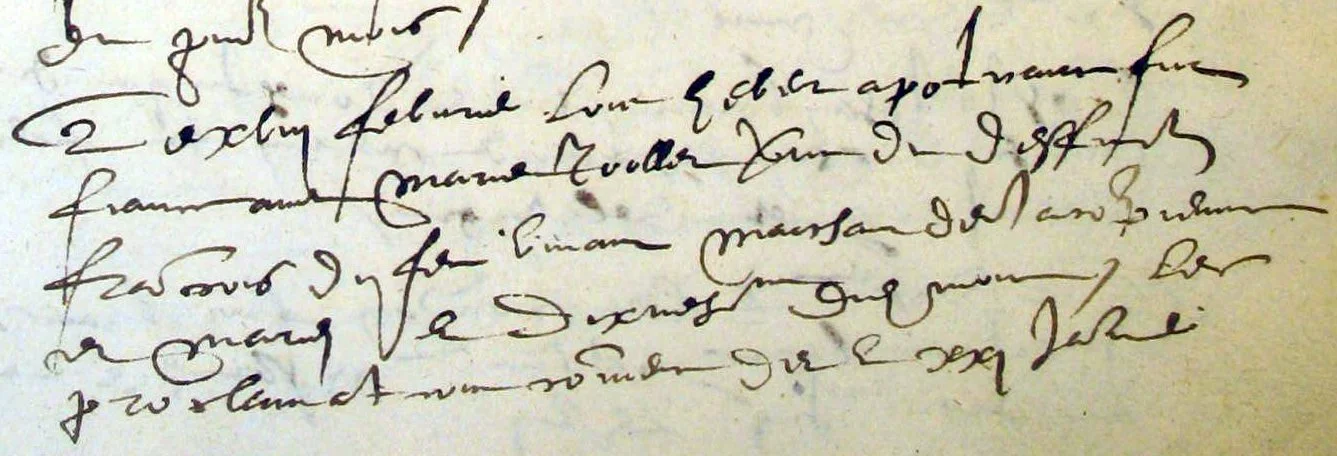

1601 marriage of Louis and Marie in Paris (Archives nationales de France)

Translated, the record reads: “On February 18, Louis Hebert, apothecary was engaged to Marie Raullet, widow of the late Francois Dufeu merchant living in Compiegne, and wedded on the 19th of said month, with the proclamations having started on January 21.”

The couple had at least three children, all born in Paris:

Anne (?–1620)

Marie Guillemette (ca. 1604—1684)

Guillaume (?–1639)

In the years following their marriage, Louis and Marie lived at several addresses in Paris: in the University quarter, on rue Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet, in the parish of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, in the faubourg Saint-Germain, and again in the parish of Saint-Sulpice. Around 1602, they settled for a time in a poorer neighbourhood, in a small, dilapidated house on rue de la Petite Seine. It was here that Louis established his own apothecary practice, but his financial difficulties continued.

The Allure of New France

By the early seventeenth century, France sought to expand its presence in North America. King Henri IV encouraged colonial ventures that brought together Protestant merchants and Catholic nobles in the pursuit of trade and settlement. A central figure in these efforts was Pierre Dugua de Mons, a Huguenot nobleman who in 1604 received a royal patent granting him a monopoly over the fur trade in exchange for establishing a permanent colony in the Terres Neuves (“New Lands”) of North America. Dugua’s expeditions founded a settlement at Île Sainte-Croix (1604–05) and later at Port-Royal in Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia) in 1605.

Louis became linked to this circle through a family connection: his maternal cousin Claude Pajot married Jean de Biencourt, Sieur de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just. Poutrincourt, a Catholic nobleman and close associate of Dugua, had received the Port-Royal seigneurie on the condition that he help colonize it. Through this marriage connection, Louis was introduced to the principal leaders of the New France venture.

Foraging in Acadia, artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (November 2025)

On March 24, 1606, Louis signed a one-year contract with Dugua de Mons to serve as an apothecary in New France for a salary of 100 livres, with 50 livres paid in advance, plus food and maintenance. On the same day, he granted a general power of attorney to his wife Marie. The agreement, signed before notaries Mathieu Bontemps and Guillard in Paris, identifies Louis as a maître-apothicaire épicier (master apothecary grocer) residing on rue de la Petite Seine. A few months later, on August 8, before the same notaries, Marie sold the family home on rue de la Petite Seine to the duchess Marguerite de Valois for 2,160 livres, as the duchess planned to build a château along the street. The deed confirms the names of Marie’s parents and indicates that her mother was then living on rue Haute-Feuille in Paris, near the school of medicine.

In early May 1606, Louis travelled to La Rochelle to embark on le Jonas. After delays caused by storms, the vessel departed on May 13, 1606. Aboard were an illustrious group: Dugua de Mons, Poutrincourt, the explorer Samuel de Champlain, and lawyer-turned-historian Marc Lescarbot, among others. They arrived at Port-Royal on July 26, 1606.

From late July to November 1606, Louis took an active role in building a sustainable colony at Port-Royal. Under Poutrincourt’s direction, he conducted soil fertility tests by sowing experimental plots of wheat, rye, hemp, and other seeds. He identified local plants with medicinal and nutritional potential and tended to the health of the colonists.

In early September 1606, Louis accompanied Poutrincourt, Champlain, and a small crew on an exploratory voyage along the coast of present-day Maine and Massachusetts. Their aim was to find potential new settlement sites to the south. The group stopped at Île Sainte-Croix, before reaching a place Champlain called Port Fortuné (Stage Harbor in Cape Cod) on October 2. They encountered Almouchiquois communities—southern New England Indigenous groups likely including the Nauset and other Algonquian peoples—experiencing both peaceful exchanges and hostile incidents. A night attack resulted in the deaths of four of the five Frenchmen left ashore. Louis treated the wounds of Robert Gravé, son of François Gravé du Pont, a longtime associate of Champlain, who had sustained severe injuries. Gravé ultimately recovered under Louis’s care. The party returned to Port-Royal on November 14, 1606.

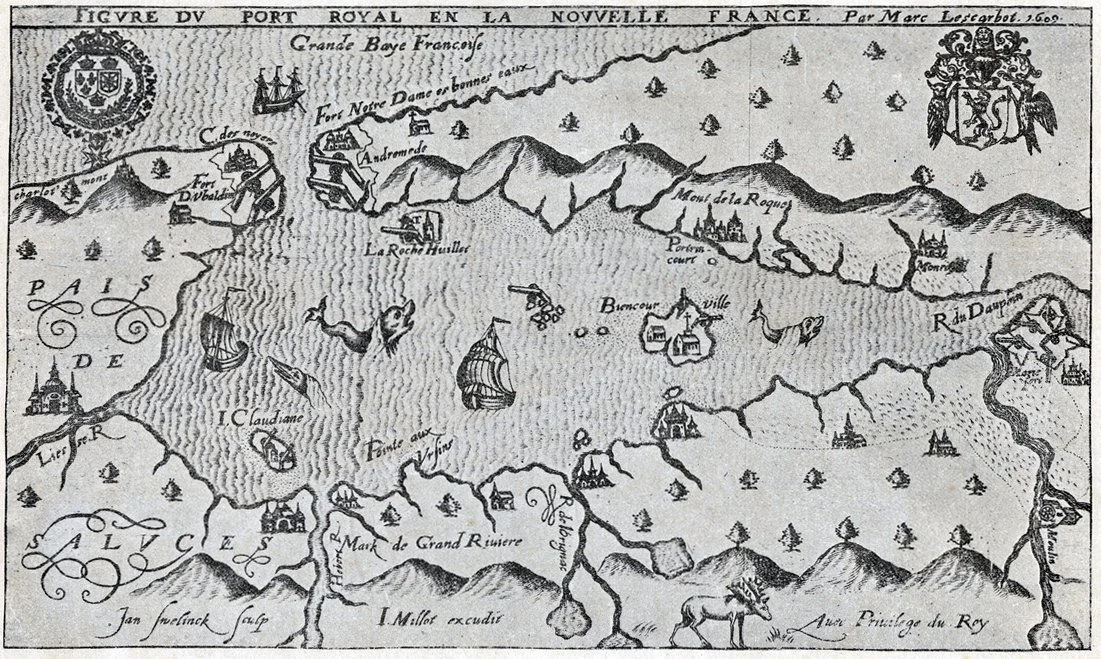

“Figure du Port-Royal en Nouvelle-France" (Map of Port-Royal in New France), 1609 map drawn by Louis’s travel companion, Marc Lescarbot (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

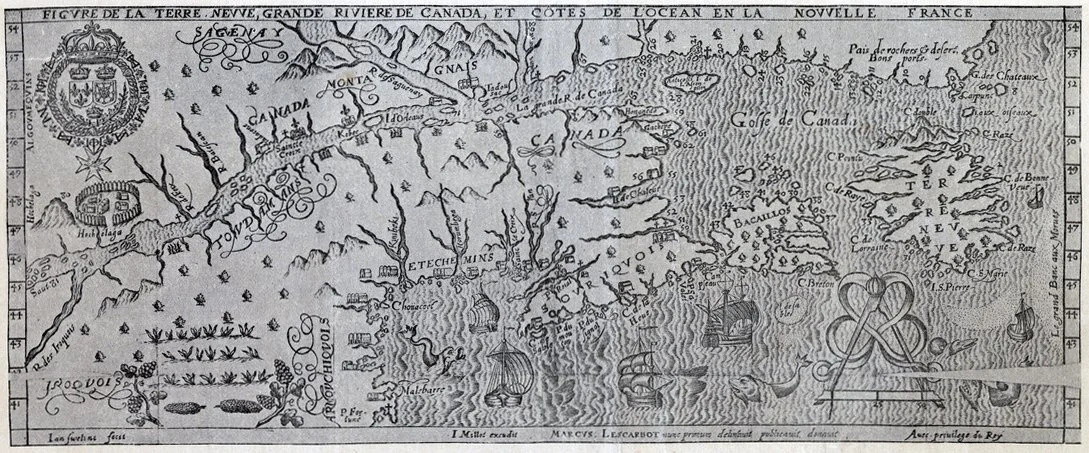

“Figure de la Terre Neuve grande rivière de Canada et costes de l'océan en la Nouvelle-France" (Map of Newfoundland, the great river of Canada, and the coasts of the ocean in New France), 1612 map drawn by Marc Lescarbot (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Louis’s Early Voyages to Acadia

During the winter of 1606–1607, Louis participated fully in the daily life of the Port-Royal settlement. With a population of fewer than fifty people and limited outside contact, the colony relied heavily on his skills. He helped manage food stores, treated cases of scurvy, and likely maintained the gardens and grain fields planted earlier in the year. In the summer of 1607, the settlers were forced to withdraw after the French Crown revoked Pierre Dugua de Mons’s exclusive fur-trade monopoly, which had financed the Acadian venture and granted him legal control of coastal trade. Without this monopoly, Dugua could no longer fund or supply the settlement, and Port-Royal had to be abandoned. The colonists harvested their grain and seeds to bring back as evidence of the land’s potential, departed Port-Royal aboard the Jacques on September 3, 1607, and reached Saint-Malo about a month later. Louis remained in France until 1611.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (November 2025)

In late 1610 or early 1611, Poutrincourt sought new investors to resupply Port-Royal, including two Jesuit priests. Hearing of renewed plans for Acadia, Louis chose to return. On January 26, 1611, he sailed from Dieppe aboard a ship commanded by Poutrincourt’s twenty-year-old son, Charles de Biencourt. Among those on board were the Jesuit fathers Pierre Biard and Ennemond Massé, sent to establish a mission in Acadia. After an unusually long Atlantic crossing of nearly four months, the ship arrived at Port-Royal in May 1611. Between 1611 and mid-1613, Louis lived and worked at Port-Royal much as before—cultivating land, collecting wild plants, and tending the sick. He treated, among others, Actodin, son of the Mi'kmaq chief Membertou.

The colony’s internal politics soon became strained. With Poutrincourt back in France, Biencourt—now in command—clashed with the Jesuit missionaries over authority and the allocation of resources. The Jesuits expected material support for their mission; Biencourt, struggling to feed the settlement, resented the additional demands. Louis found himself in the middle. In March 1612, he attempted to mediate between Biencourt and the Jesuits. After roughly three months of conflict, the Jesuits chose to relocate farther south and left Port-Royal on June 24, 1612.

The winter of 1611–1612 brought severe food shortages to Port-Royal, resulting in strict rationing beginning in late November. In early 1613, Biencourt led several men inland in search of provisions, while Louis remained at the post with only two companions. In May 1613, a royal letter arrived clarifying that the Jesuits—who had briefly returned to Port-Royal after their failed settlement attempt—were free to depart if they wished; they soon sailed back to France.

Not long after, disaster struck the colony from an external enemy. In the fall of 1613, Captain Samuel Argall, an English privateer from Virginia, attacked Port-Royal. His men looted what they could and burned the settlement to the ground. With so few defenders, Louis and the remaining colonists could offer little resistance. By October 1613, they had no choice but to return to France once again. Louis secured passage aboard the vessel Grâce de Dieu and arrived in La Rochelle toward the end of that month.

Back in France, political conditions for New France continued to shift. Poutrincourt, who had remained in France, faced legal and financial difficulties and was even imprisoned in Paris in 1613 following disputes with merchants over fur-trade profits. After his release, he sought new backing for Acadia, turning to wealthy merchants such as Georges and Macain (possibly Macquin), though enthusiasm was waning. During this period Poutrincourt appointed Louis as Biencourt’s legal representative in France, entrusting him with notarial matters, preparations for voyages, and commercial dealings connected to Port-Royal and the fur trade.

Beginning in 1613, commercial rivalry in Acadia led to repeated conflicts with other French traders. In May 1614, Biencourt’s men seized a load of furs from rival merchants on the Saint John River, sparking lawsuits in France. Over the next several years, the courts of Rouen, Saint-Malo, La Rochelle, and Paris saw a series of disputes between Biencourt’s supporters and competing traders. Louis was inevitably drawn into these proceedings. On April 28, 1618, opponents of Biencourt obtained warrants for the arrest of both Biencourt and Louis. By that time, however, Louis had already left France—he was living with Champlain’s colony at Québec.

The First Settler Family in Canada

In 1617, France’s colonial focus shifted toward the St. Lawrence valley, where Samuel de Champlain had founded Québec in 1608. After the collapse of Dugua’s monopoly, a new trading consortium—the Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo—managed the fur trade at Québec. Champlain, determined to build a lasting colony, sought experienced settlers who could cultivate the land and support a growing French population. Louis Hébert, already proven in Acadia, was an ideal candidate.

On March 6, 1617, Louis signed an engagement to work the Compagnie des Marchands in New France. Encouraged by Dugua, he agreed to a payment of 600 livres for three years, plus food. However, just days before his departure, the contract was modified: the term was reduced to two years; Louis was forbidden from charging treatment fees or trading in furs with the Indigenous; and harvests from his land were to be sold to the Company.

Louis and Marie sold most of their belongings and, with their three children and Marie’s brother Claude, travelled from Paris to Honfleur in Normandy. They set sail for Canada on March 13, possibly aboard the Saint-Étienne. After a long and difficult three-month crossing, the family landed at Tadoussac on June 14, 1617. A few weeks later, in early July, Louis Hébert, Marie Rollet, and their children arrived in Québec, becoming the first European family to establish themselves permanently in New France.

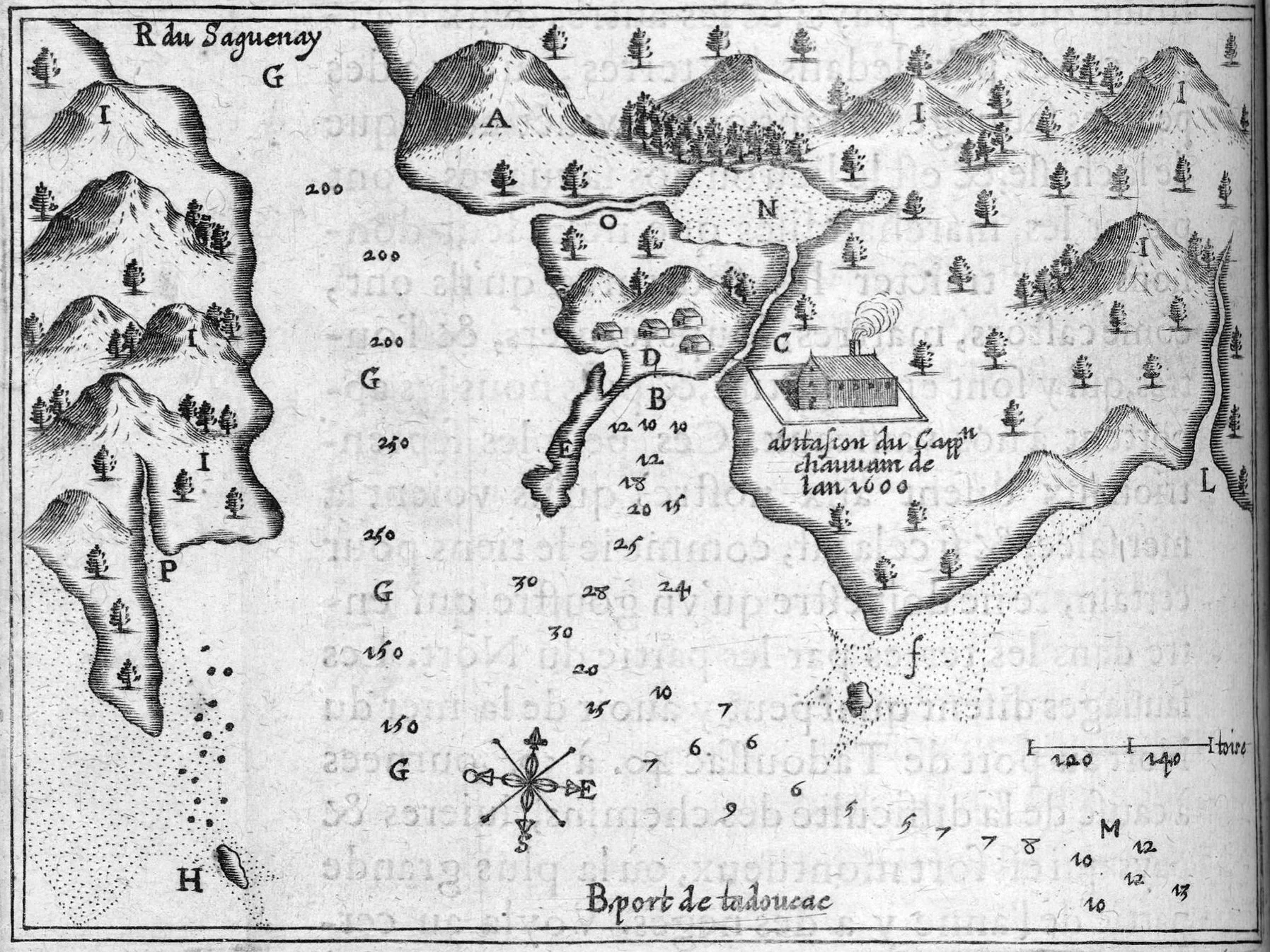

“Port de Tadoucac” [Port of Tadoussac], 1613 map by Samuel de Champlain (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

At Québec, Louis received a large, semi-wooded plot on the heights above the Habitation—the French trading post by the river—on Cap Diamant, the promontory overlooking the settlement. With his brother-in-law Claude, he quickly built a wooden house measuring roughly six metres square, with a wooden floor and hearth. After their first Canadian winter, the family realized the structure was inadequate. Around 1618, with Champlain’s support and assistance from company workmen, they built a stone house—one of the earliest stone residences in Canada. By 1620, they had an enclosed yard with livestock, crops, and fruit trees. Louis cultivated peas, beans, cabbages, pears, and various other vegetables and herbs; in his orchard, he grew apple trees and grapevines. This made Louis the first colonist of New France to live by farming.

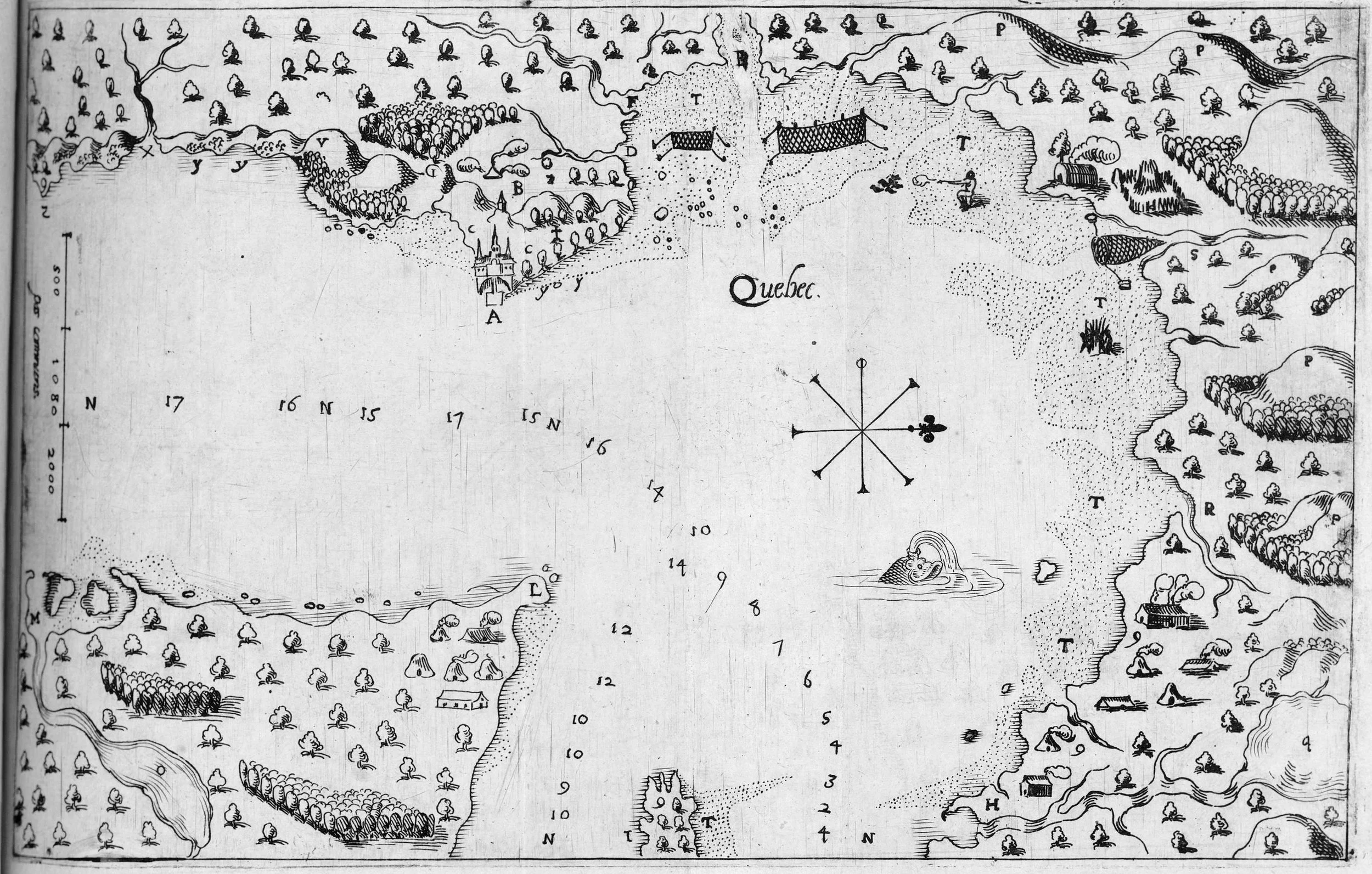

Québec, 1613 map by Samuel de Champlain (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (November 2025)

Alongside farming, Louis resumed his work as the colony’s apothecary. With a modest collection of medical books and manuals brought from France, he studied the local flora to identify useful herbs and roots. He also learned from Indigenous knowledge: Louis formed relationships with members of the Huron-Wendat and Algonquin nations, exchanging information about medicinal plants. He experimented with crops unfamiliar to Europeans, successfully growing Indian corn (maize) in his garden—a food that soon became a staple for the French, thanks to Indigenous teaching. The family adapted to New World foods, hunting or trading for moose and bear meat, geese, ducks, pigeons, eels, and beaver, and gathering pumpkins, blueberries, raspberries, and maple sap for sugar.

Marie proved equally adaptable. She likely learned food preparation and preservation techniques from Indigenous women and assisted Louis in testing new recipes and remedies.

Family Milestones

Soon after their arrival, the Hébert family cemented their roots in Canada through marriage alliances. Sometime before 1619, Anne married Étienne Jonquest, a Norman interpreter. Anne became pregnant, but neither she nor the child survived the birth. This early tragedy marked one of the first recorded family losses among the French settlers of Canada.

The Héberts’ second daughter, Marie Guillemette, married Guillaume Couillard on August 26, 1621, at Québec, in the presence of Samuel de Champlain. Guillaume, a carpenter and sailor for the Compagnie des Marchands, was 32 years old and had arrived in the colony around 1613. Louis granted the couple a portion of land adjacent to his own to establish their household. Guillemette and Guillaume went on to have at least ten children, and their numerous descendants became a significant lineage in Canada.

Louis and Marie’s only son, Guillaume, grew up in Québec and assisted his father on the family farm. In October 1634, several years after Louis’s death, he married Hélène Desportes—widely regarded as the first child of European descent born in Canada—and the couple established their household in Québec, where they had three children. Guillaume’s life was brief; he died in September 1639, only five years after his marriage, leaving Hélène a young widow with three small children. Through his descendants, however, Guillaume carried the Hébert line into the next generation of settlers who shaped early Québec.

Land Concessions

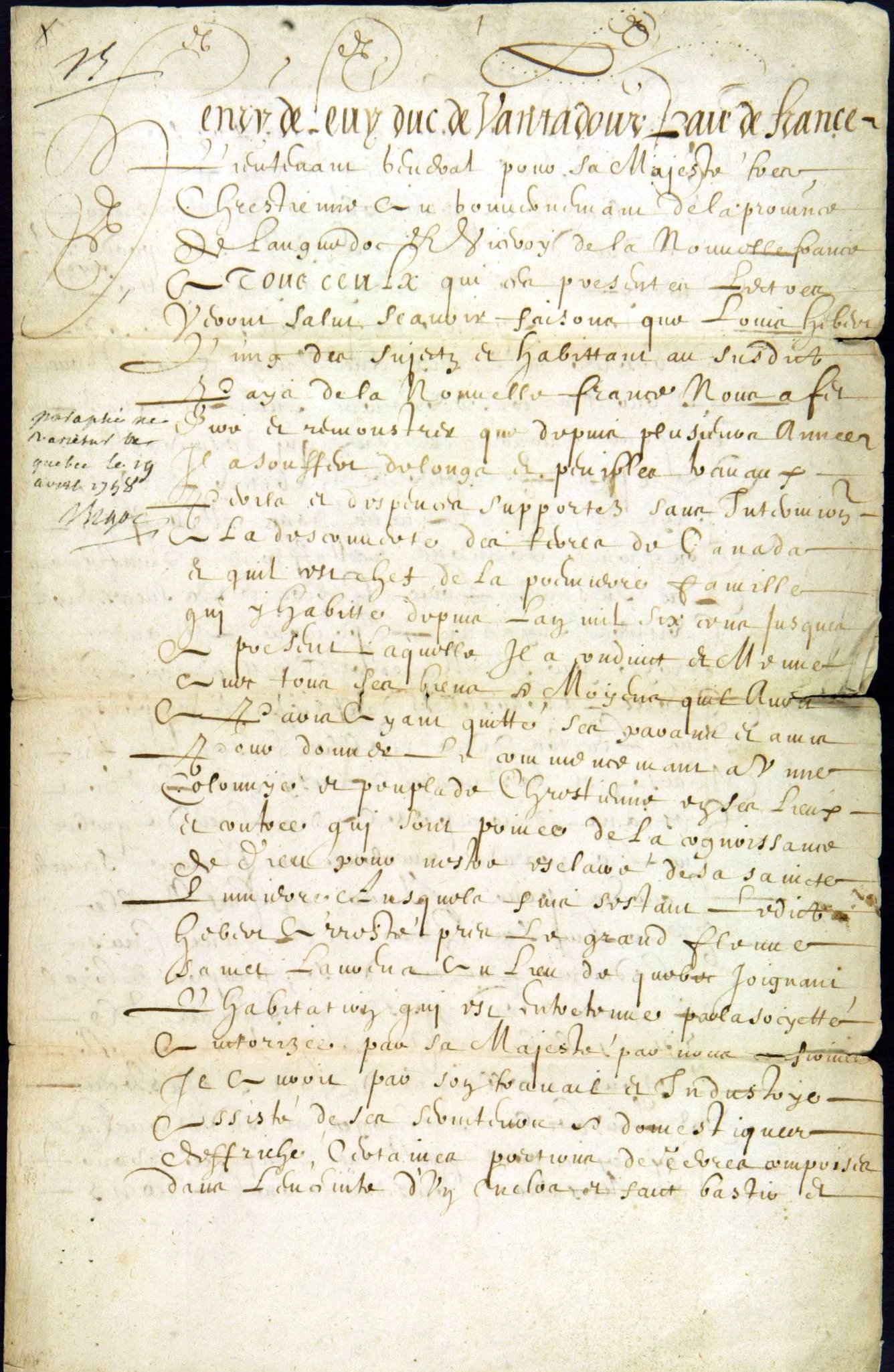

On February 28, 1626, Henri de Lévy, duke of Ventadour and vice-roi de la Nouvelle-France, formally confirmed Louis Hébert’s rights to the land he had cleared and occupied at Québec. He ratified an earlier grant made to Louis in 1623 by the duke of Montmorency, giving him full ownership—held as a noble fief—of all the cleared and enclosed land surrounding his home, along with his house and buildings on the St. Lawrence River. He also granted Louis an additional tract of one French league along the Rivière Saint-Charles, whose boundaries had been laid out by Champlain and de Caën.

Translated, the document reads:

“We are informed that Louis Hébert, one of the subjects and habitants of the aforementioned country of New France, has told us and shown us that for several years he has endured long and arduous labour, perils and expenses without interruption in the discovery of lands in Canada, and that he is the head of the first family to have lived there since the year 1600 [sic] to the present, which he leads, and even, with all the goods and means he had in Paris, having left his relatives and friends to start a colony and Christian peoples in these places and regions that are deprived of the knowledge of God for not being enlightened by His holy light, to which ends the said Hébert settled near the great Saint Lawrence River in the place of Quebec, joining the settlement maintained by the society authorized by His Majesty and confirmed by us, he would, through his labour and industry, assisted by his domestic servants, have cleared a certain portion of land enclosed within a walled enclosure and built a dwelling for himself, his family and his livestock; of which lands, dwellings and enclosures he would have obtained from Monsieur le Duc de Montmorency, our predecessor, viceroy, the gift and grant in perpetuity by letters sent on Saturday, the fourth of February, sixteen hundred and twenty-three;

We, for the reasons stated above and to encourage those who may hereafter wish to populate and inhabit the said country of Canada, have granted, ratified and confirmed, do grant, ratify and confirm to the aforementioned Louis Hébert and his successors and heirs, and by virtue of the power granted to us by His Majesty, all the aforementioned cleared arable lands included within the enclosure of the said Hébert, together with the house and buildings, as well as everything that extends and comprises at the said place of Quebec, on the great river or St. Lawrence River, to be enjoyed as a noble fief for him, his heirs and assigns in the future, as his own and loyal acquisitions, and to dispose of them fully and peacefully as he sees fit, all of which belongs to the fort and castle of Quebec, subject to the charges and conditions that we shall impose hereafter, and for the same reasons, we have furthermore granted to the said Hebert and his successors, heirs and descendants, a tract of land measuring one French leagues in length, located near the said Quebec on the Saint Charles River, which has been marked out and demarcated by Messrs. de Champlain and de Caen, for them to possess, clear, cultivate and inhabit as he sees fit, under the same conditions as the first donation, expressly prohibiting and forbidding any person of any rank or condition whatsoever from disturbing or preventing him from possessing and enjoying these lands, houses and enclosures, enjoining Sieur de Champlain, our Lieutenant General in New France, to maintain the said Hébert in his aforementioned possession and enjoyment against all and sundry, for such is our will.”

By these letters, Louis effectively became a seigneur, with the fief on the height of Cap Diamant (later called Sault-au-Matelot) and another by the St. Charles (later called le fief Saint-Joseph or fief Lespinay).

First page of the 1626 grant and ratification (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In execution of the royal grant confirmed to Louis by the Duke of Ventadour on February 28, 1626, Samuel de Champlain formally placed Louis in possession of his fief on August 8, 1626. Acting as Ventadour’s lieutenant in New France, Champlain travelled to a site about one league from Québec, on the north side of the Rivière Saint-Charles opposite the Récollet convent, where he marked out the boundaries of the concession: a tract measuring a quarter-league in width by four league in length, consisting of woodlands, pastures, and small streams. Champlain recorded the act on site, confirming Louis’s possession of the property as ordered by the royal patent.

Death of Louis Hébert

By 1626–1627, Louis Hébert was about 52 years old and had lived a demanding life in Québec. He likely died at Québec on January 25, 1627, following a fatal fall, possibly on the ice.

Samuel de Champlain recorded the death in his Journal ès découvertes de la Nouvelle France:

"On 25 January, Hébert fell and died; he was the first head of a family residing in the country who lived off the land he cultivated.”

Champlain’s 1632 account provides the earliest and most reliable information. Later writers—including Sagard (1636) and Le Clercq (1691)—attributed Louis’s death to illness, but these reflect later interpretations rather than Champlain’s brief contemporary notice. Louis was buried in the Récollet cemetery at Notre-Dame-des-Anges, most likely on January 25 or within the following days. The exact details of his burial remain unknown because the Récollet archives were destroyed and the original burial register has been permanently lost. Later testimony by his daughter Guillemette nevertheless confirms his burial in the Récollet cemetery.

Father Le Caron performed the last rites. Sagard adds (likely apocryphally) that many Indigenous friends—Huron and Montagnais—gathered at Louis’s bedside in his final hours. According to Sagard, Louis blessed his wife and children, urged those present to support one another and continue God’s work in New France, and died peacefully after giving a final gesture of benediction.

Marie, now a widow at 49, was left with two surviving children in Québec (Guillemette and Guillaume) and several grandchildren. Under French custom, half of Louis’s estate belonged outright to Marie as the widow’s share, and the remaining half was to be divided among the children. To secure the family’s future, Marie would soon consider remarriage—but not before navigating a turbulent period about to unfold in New France.

War and Occupation

From the time of Louis and Marie’s arrival in 1617, the small settlement at Québec was plagued by overlapping tensions. Shifting fur-trade monopolies—first the Rouen merchants’ company, then the Montmorency–de Caën group, and finally Richelieu’s newly formed Compagnie des Cent-Associés—left the colony in a near-constant state of administrative uncertainty. These private companies prioritized profit over permanent settlement. Champlain, tasked by the Crown with building a functioning colony, struggled against merchant interests that resisted the burdens of agriculture, defence, and population growth. Religious politics added further strain: the Récollets had established the first missions, but the arrival of the Jesuits in 1625, backed by Richelieu’s influence at court, created new competition for authority, while the dominant merchant family, the de Caëns, were Huguenots.

Following Louis’s death in 1627, Québec remained a small, under-supplied French outpost on the St. Lawrence, increasingly vulnerable as war broke out between France and England that same year. The Compagnie des Cent-Associés was intended to revitalize the colony, but in the summer of 1628, an English fleet commanded by David Kirke seized control of the river approaches. Kirke’s squadron sailed to Québec, demanded Champlain’s surrender, and withdrew only when he refused—then intercepted French shipping on its way upriver. On 17 July 1628, Kirke captured the convoy led by Claude de Roquemont, carrying provisions, munitions, and hundreds of colonists. Québec lost the relief it desperately needed. Through the winter, the settlement endured deepening hunger and illness with no prospect of resupply, conditions that paved the way for Québec’s bloodless capitulation to the Kirke brothers in 1629—years that Marie and her children lived through on the Hébert lands Louis had cleared.

A Third Marriage for Marie

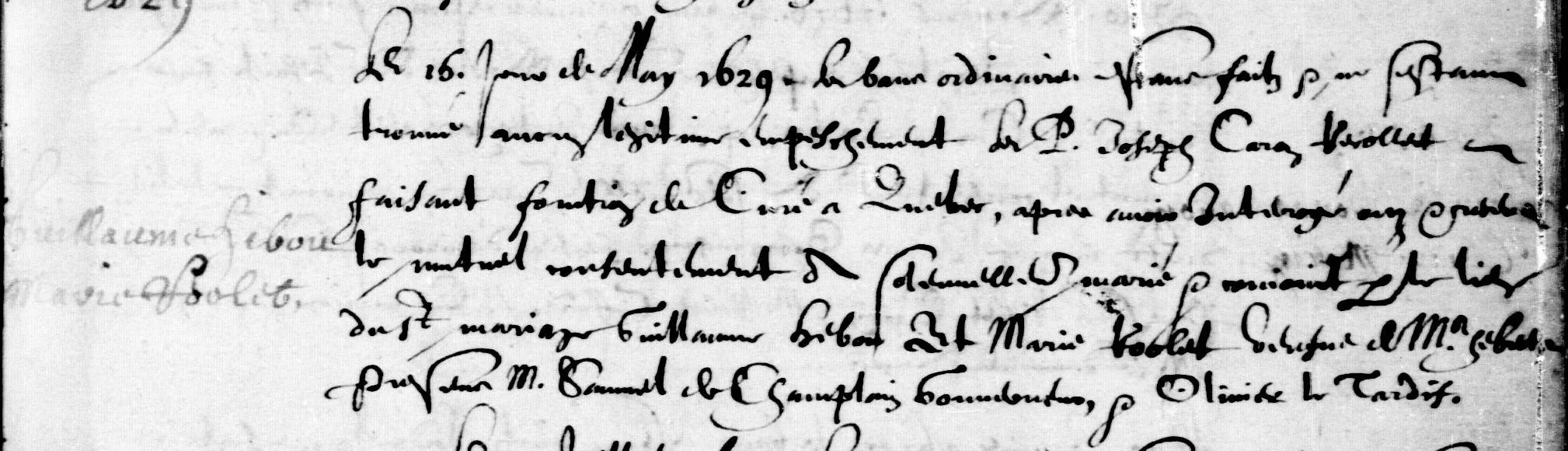

At the age of 51, Marie married her third husband, Guillaume Huboux. The ceremony took place on May 16, 1629, in Québec, with the Récollet priest Joseph Caron officiating and Samuel de Champlain and Olivier Letardif serving as witnesses. The couple settled on the Hébert property.

1629 marriage of Marie and Guillaume Huboux (Généalogie Québec)

A Short-Lived English Occupation

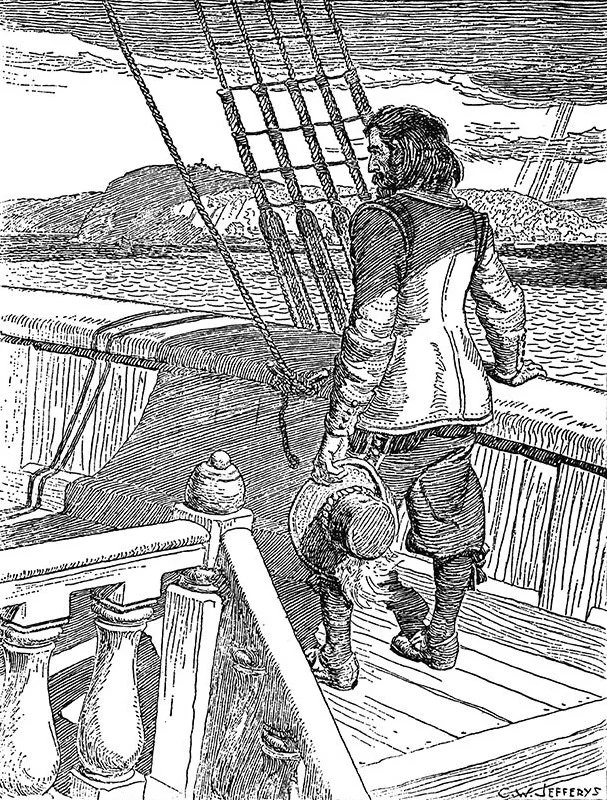

“Champlain Leaving Quebec, A Prisoner,” 1942 drawing by Charles W. Jefferys

On July 19, 1629, Quebec capitulated to Louis and Thomas Kirke – the English took possession of the Habitation, the few cannons, and whatever meager supplies remained. Champlain and about 20 French, mostly men of the Company, were taken prisoner and transported to England. But importantly, families and colonists who wished to remain were allowed to stay under English rule, as part of the terms of surrender. Marie and her family were among those who elected to stay in Quebec despite the English occupation. They were one of only a handful of French families who stayed through the occupation.

During these years under the Kirke brothers, Marie and Guillaume continued to live on their land, as did her children: Guillaume and his sister Guillemette, along with Guillemette’s husband Guillaume Couillard and their children. The Kirkes imposed their authority but left resident families largely undisturbed. When Champlain departed in 1629, he was forced to leave behind his two adopted Indigenous girls, Espérance and Charité. Marie and her daughter Guillemette took charge of their care. Later Jesuit accounts describe Marie’s home as a place where Indigenous girls were lodged and taught French and Christianity during the 1630s.

Also left behind during the occupation was a young enslaved African boy, captured in Madagascar or on the coast of Guinea and purchased by David Kirke. He is known to history as Olivier Le Jeune, generally regarded as the first documented enslaved African in New France. Kirke sold the boy in Québec, and he ultimately ended up in the Couillard household, either sold or transferred to Olivier Le Tardif and then given to Guillaume Couillard and Guillemette Hébert, with whom Marie was living.

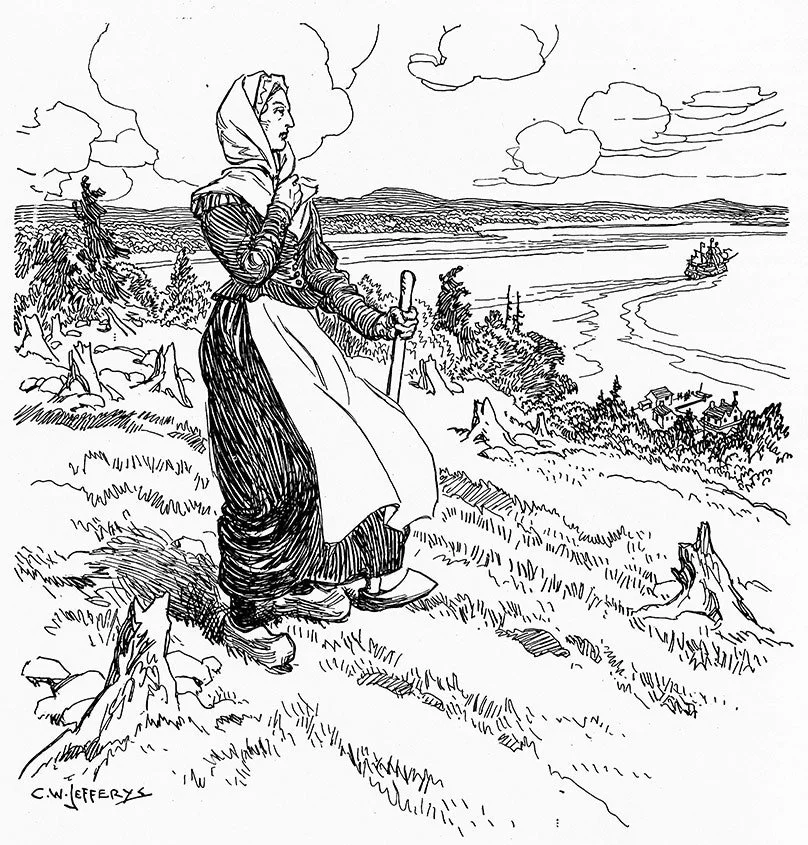

“Marie Hebert, The Mother of Canada,” 1934 drawing by Charles W. Jefferys

Jefferys' notes about this picture in Canada's Past in Pictures: “In the picture she is seen watching from one of her fields on the edge of the cliff the departure of the last English ship bearing away the French colonists. At the base of the cliff is shown a glimpse of the wharf and the buildings of the habitation, while in the distance extends the Beauport shore of the St. Lawrence. Marie wears the kerchief, the short thick jacket and heavy skirt, and the wooden shoes of the pioneer women of that time. The clumsy mattock or hoe, used for breaking up the ground, and the stony field beset with stumps suggest the hard rough work to which she had set her hands.”

The Return of French Rule

The Kirke occupation ultimately proved temporary. Unbeknownst to Kirke, England and France had already signed the Treaty of Susa in April 1629, before Québec’s capture; the treaty stipulated that any conquests made afterward were to be returned. When Champlain arrived in London in 1630 as a paroled prisoner, he learned of this and lobbied vigorously for Québec’s restoration. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632) formally returned New France to France. By July 1632, the Kirke brothers evacuated Québec, and Champlain returned in the spring of 1633 as reappointed governor.

Marie’s Later Years

On September 15, 1634, a few weeks before her son Guillaume’s wedding, Marie, her husband Guillaume Huboux, her children, and her son-in-law Guillaume Couillard appeared before the court at Québec to formalize a complete division of the lands, houses, and livestock developed by the Hébert–Rollet family since their arrival. They appointed two experts, Henri Pinguet and Nicolas Priort, who surveyed and measured the Sault-au-Matelot property and divided it into two equal halves: one portion for Guillaume Couillard and Guillemette Hébert, and the other for Guillaume Huboux, Marie Rollet, and Guillaume Hébert. The agreement set out precise boundaries, shared access paths, the communal use of a spring and certain buildings (including a brewery), and the division of houses, gardens, and outbuildings. All parties swore to uphold the settlement before witnesses, including Champlain.

This division provides a clear picture of the Hébert–Rollet estate. Within their enclosure, the family possessed:

A stone house containing a brewery

Three principal buildings, including one measuring 38 by 19 feet with a chimney, and two structures containing a barn and stable

A watermill, a lime kiln and a fountain

Paths connected these structures to the fountain and to the Habitation.

Their landholdings included the Sault-au-Matelot fief of 18 arpents, a plot of 100 arpents extending from Sault-au-Matelot west of the Fort, and a quarter-league on the left bank of the Rivière Saint-Charles.

During these years, Marie continued to shelter and educate Indigenous girls entrusted to her by the Jesuits. Because the Jesuit college for boys and the Ursuline convent for girls would not be founded until 1635 and 1639 respectively, Marie’s home served as an essential place of learning for young Indigenous converts. Jesuit records from the 1630s frequently name her as godmother to baptized children of the Huron and Innu.

Death of Marie Rollet

Marie Rollet died at the age of 71 and was buried on May 27, 1649, in the Notre-Dame parish cemetery at Québec.

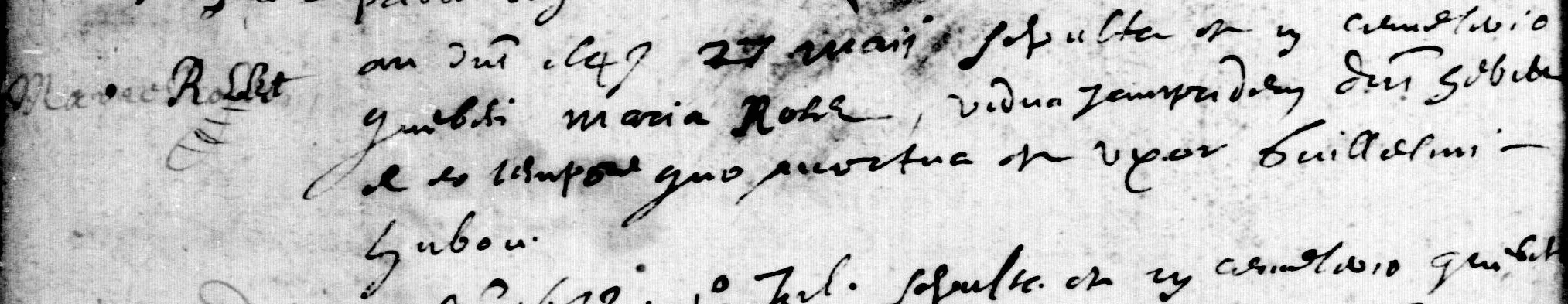

1649 burial of Marie Rollet (Généalogie Québec)

Marie had spent more than three decades in New France—from 1617 to 1649, aside from the brief English occupation—and was widely respected at the time of her death.

Commemoration

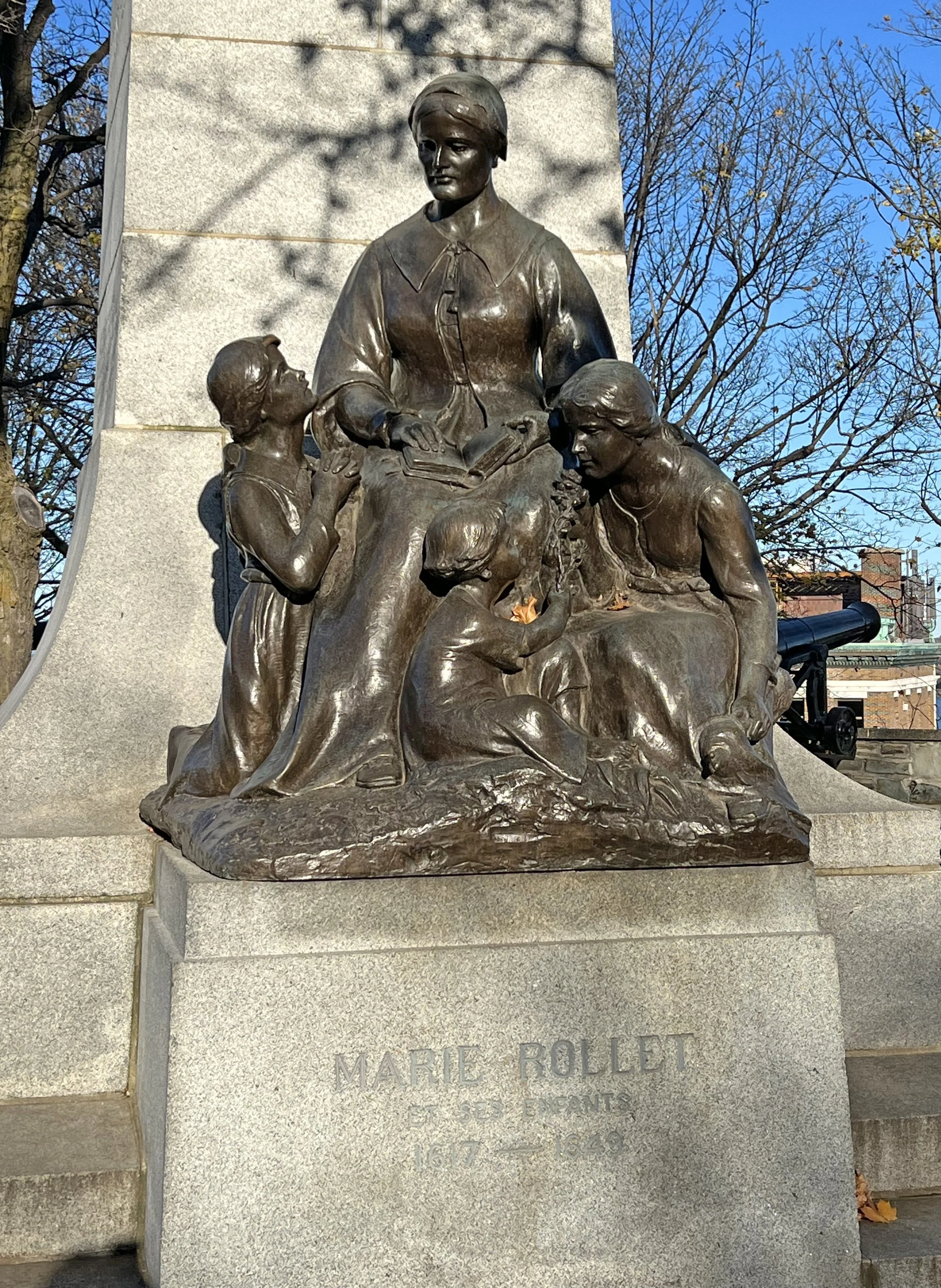

Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet are remembered as the first family of French Canada, and their contributions have been honoured in numerous ways. In 1917, Québec planned to celebrate the tercentenary of their arrival. Although the First World War delayed the tribute, a grand monument to Louis Hébert, designed by the sculptor Alfred Laliberté, was unveiled on September 3, 1918, in the garden of Québec City Hall (Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville). The bronze monument depicts Louis Hébert standing on a pedestal, holding a sheaf of wheat and a sickle. At his side is a figure representing his son-in-law, Guillaume Couillard, leaning on a plow. On the opposite side sits Marie Rollet, portrayed with an open book and her three children—a symbol of her role in teaching and nurturing youth in New France. The pedestal also bears a list of the earliest settlers of Québec from 1617 to 1638.

The Louis Hébert monument in front of the Hôtel-de-Ville, circa 1920 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In the late 1970s, the monument was relocated to Parc Montmorency on Cap-Diamant, on land corresponding roughly to the original Hébert farm.

The monument as it appears today, in Parc Montmorency in Québec (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

The monument as it appears today, in Parc Montmorency in Québec (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

Today, the couple’s legacy is visible throughout the region. A street in Old Québec bears the name Rue Hébert, and another, Rue Couillard, lies on or near land once belonging to the family. Across the St. Lawrence, Rue Marie-Rollet in Lévis commemorates Marie. Parks, schools, and public buildings—including the federal Marie Rollet Building in Ottawa—also carry their names. In 1984, Canada Post issued a stamp depicting Louis Hébert sowing seeds.

The story of Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet continues to be taught as part of Canadian heritage, emphasizing their resilience, faith, and cooperation with Indigenous peoples.

Early Settlers at the Heart of Québec’s Beginnings

Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet stand at the very beginning of permanent French settlement in Canada, not as symbols but as working people who built a life through persistence, skill, and faith. Their years at Québec—marked by hardship, experimentation, loss, and renewal—helped shape the foundations of a community that would grow long after their time. Through their children and descendants, their legacy endures in thousands of French-Canadian families today, a reminder that the story of New France began not only with governors and explorers, but with ordinary families determined to make a home on unfamiliar soil.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"[AN LL958] - Paris, Saint-Sulpice (Paris, France) - État civil (Naissances) | 1557 – 1604," digital images, Geneanet (https://www.geneanet.org/registres/view/5602/21 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), marriage of Louis Hebert and Marie Raullet, 19 Feb 1901, Paris (St-Sulpice), image 21 of 76 ; citing original data : Centre historique des Archives nationales à Paris.

"Histoire," Ville de Sedan (https://sedan.fr/decouvrir-sedan/histoire/ : accessed 27 Nov 2025), updated 4 Sep 2023.

Jacques Mathieu, La vie méconnue de Louis Hébert et Marie Rollet (Québec, Septentrion, 2017).

Jacques Mathieu, “HÉBERT, LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hebert_louis_1E.html : accessed 25 Nov 2025), vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/hebert-4 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), entry for HÉBERT, Louis (reference #350070), updated on 29 May 2017.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/rolet/-rollet : accessed 25 Nov 2025), entry for ROLET / ROLLET, Marie (reference #390073), updated on 9 Feb 2025.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/couillard : accessed 27 Nov 2025), entry for COUILLARD, Guillaume (reference #241031), updated on 22 Apr 2022.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/18 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Louis HEBERT and Marie ROLET, union 18.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/75096 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Anne HEBERT, person 75096.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/85 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Guillaume COUILLARD and Guillemette HEBERT, union 85.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/223 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Guillaume HEBERT and Helene DESPORTES, union 223.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/25064 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), dictionary entry for Guillaume HEBERT, person 25064.

Gilles Brassard, "189. Marie Rolet, acte de baptême !," Conversations avec mes ancêtres (https://conversationsancetres.wordpress.com/2024/04/22/189-marie-rolet-acte-de-bapteme/ : accessed 27 Nov 2025).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66317 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), marriage of Guillaume Couillard and Guillemette Hebert, 26 Aug 1621, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66320 : accessed 25 Nov 2025), marriage of Guillaume Hebert and Helene Desportes, 1 Oct 1634, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66318 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), marriage of Guillaume Hubou and Marie Rolet, 16 May 1629, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/68761 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), burial of Marie Rolet, 27 May 1649, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Collection Centre d'archives de Québec - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/367380 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), "Documents concernant Louis Hébert," 2 Feb 1626 to 22 Dec 1768, reference P1000,S3,D959, Id 367380.

“Collection Centre d'archives de Québec - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/998069 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), "Don, ratification et confirmation par Henry de Lévy, duc de Ventadour, pair de France, lieutenant-général pour Sa Majesté Très Chrétienne au gouvernement de la province de Languedoc et vice-roi de la Nouvelle-France, à Louis Hébert et ses successeurs et héritiers" [transcription], 28 Feb 1626, reference P240,D285,P1, Id 998069.

“Fonds Intendants - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/93511 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), "Acte de mise en possession par Samuel de Champlain, capitaine pour le Roi en la Marine, lieutenant de monseigneur le duc de Ventadour, des terres accordées au sieur Louis Hébert par ledit duc de Ventadour le 28 février 1626," 8 Aug 1626, reference E1,S4,SS1,D132,P2, Id 93511.

"Collection Seigneuries - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/998090 : accessed 27 Nov 2025), " Acte de mise en possession par Samuel de Champlain capitaine pour le Roi en la marine, lieutenant de Mgr le duc de Ventadoour, des terres accordées au Sieur Louis Hébert par le dit duc de Ventadour le 28 février 1626" [transcription], 8 Aug 1626, reference P240,D285,P2, Id 998090.

“Collection Seigneuries - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/998114 : accessed 28 Nov 2025), "Acte de partage du fief du Sault-au-Matelot entre Guillaume Couillard, Guillemette Hébert, sa femme, Guillaume Hubou et Marie Rollet, sa femme, ci-devant veuve de Louis Hébert, et Guillaume Hébert, tous héritiers de Louis Hébert," 15 Sep 1634, reference P240,D285,P4, Id 998114.

Thomas Peace, "Pierre Dugua de Mons," in The Canadian Encyclopedia (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/pierre-du-gua-de-monts : accessed 25 Nov 2025), article published 20 Jun 2013, updated 17 Dec 2019.

W. Austin Squires, “ARGALL (Argoll), Sir SAMUEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/argall_samuel_1E.html : accessed 25 Nov 2025), vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.

John S. Moir, “KIRKE (Kertk, Quer(que), Guer), Sir DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kirke_david_1E.html : accessed 27 Nov 2025), vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–.

Samuel de Champlain, Journal ès découvertes de la Nouvelle France (Paris : [publisher not identified], 1830.), 144-145, digitized by Canadiana (https://n2t.net/ark:/69429/m0sb3ws8kg63 : accessed 27 Nov 2025).

François Droüin, "Une chute fatale : mort et sépultures à Québec au début du XVIIe siècle," Cap-aux-Diamants, number 128, winter 2017, pages 17–20, digitized by Érudit (https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cd/2017-n128-cd02866/84139ac.pdf : accessed 27 Nov 2025).

Marcel Trudel and Mathieu d'Avignon, “Samuel de Champlain,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain : accessed 27 Nov 2025), published 29 Aug 2013, updated 11 Jun 2021.

Josiane Lavallée, "Marie Rollet," in The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/marie-rollet : accessed 27 Nov 2025), published 21 Feb 2018, last edited 26 Mar 2018.

Marcel Trudel, “CHARITÉ, ESPÉRANCE, FOI (Charity, Hope, Faith),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/charite_1E.html : accessed 27 Nov 2025), vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–.

“Population: Religious Congregations,” Canadian Museum of History (https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/religious-congregations/ : accessed 27 Nov 2025), with original research by Claire GOURDEAU, M.A., historian.

“Population: Slavery,” Canadian Museum of History (https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/slavery/ : accessed 27 Nov 2025), with original research by Arnaud BESSIÈRE, Ph.D., CIEQ – Université de Montréal.

Charles W. Jefferys, "Marie Hebert, The Mother of Canada,” C.W. Jefferys (https://www.cwjefferys.ca/marie-hebert-the-mother-of-canada : accessed 27 Nov 2025).