Julien Bouin dit Dufresne & Marguerite Berrin

Discover the remarkable story of Julien Bouin dit Dufresne, a former Carignan-Salières Regiment soldier from Anjou, France, and Marguerite Berrin, a Paris-born Fille du roi. From their marriage in 1675 to their life as settlers in New France, this biography traces their origins, family, and enduring legacy in Québec history.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Julien Bouin dit Dufresne & Marguerite Berrin

From Soldier and Fille du roi to Settlers in New France

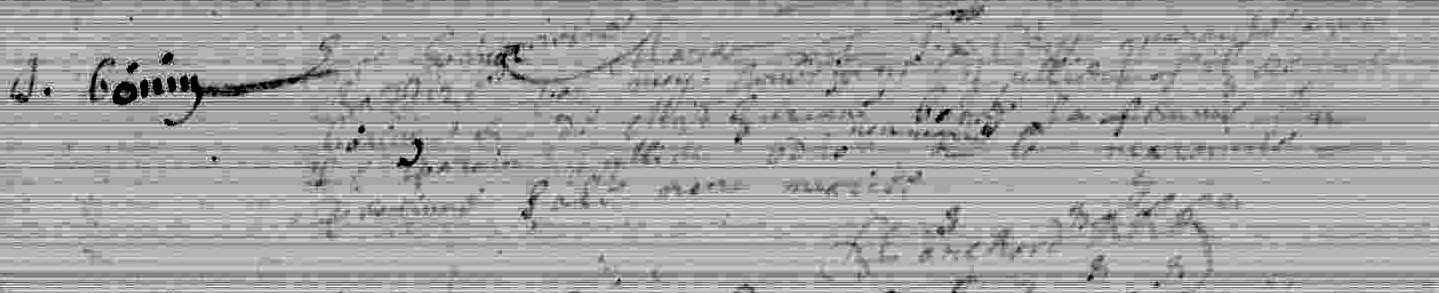

1640 Baptism of Julien Bouin (Archives départementales de Loire-Atlantique)

Location of Montrelais in France (Mapcarta)

His parents were married in the same parish on June 29, 1627. His mother, Mathurine, was buried on April 1, 1651, and his father on December 21, 1658, both in the parish cemetery of Saint-Pierre in Montrelais.

Julien was the youngest of at least eight children, all baptized in Montrelais. His known siblings were Jean (born 1628), Perrine (born 1630), Mathurine (born 1632), Julien (born 1633), twins Julien and Françoise (born 1635), and Mathieu (born 1637).

Located about 90 kilometres southwest of Paris, Montrelais is in the present-day department of Loire-Atlantique. Considered a “rural commune with dispersed homes,” it had a population of 843 inhabitants as of 2022.

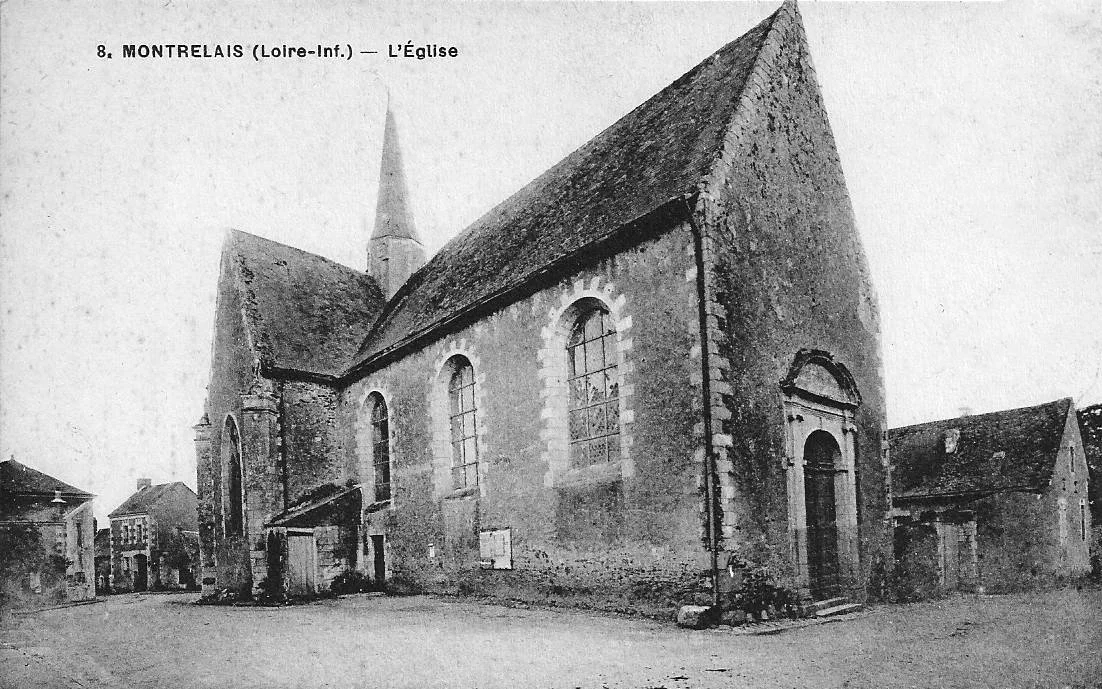

Montrelais, circa 1905-1915 postcard (Geneanet)

Church of Saint-Pierre in Montrelais, 1928 postcard (Geneanet)

A Soldier in the Carignan-Salières Regiment

In the mid-17th century, Montrelais was a small rural parish, situated along the Loire River near the border with Bretagne. Life in the village revolved around agriculture, with most families engaged in farming grain, raising livestock, or tending vineyards. The local seigneur and parish priest held significant influence, and the Catholic Church played a central role in daily life. Like much of rural France at the time, Montrelais was shaped by rigid social hierarchies and subsistence living, with limited opportunity for advancement. Enlistment in the Carignan-Salières Regiment offered young men a rare chance to leave the confines of village life and seek new opportunities in New France.

“Officer and soldiers of the régiment de Carignan-Salières, 1665–1668," drawing by Francis Back (Canadian Military History Gateway)

Julien was recruited into the Saurel (Sorel) company of the Carignan-Salières Regiment, commanded by Captain Pierre de Saurel. He and his fellow soldiers boarded the ship La Paix and arrived in Canada in August 1665. [Note: Two soldiers named Dufresne remained in Canada after their military service—one from the Saurel company and one from the La Colonelle company. While most researchers place Julien in Saurel’s company, some have argued that, given his later residence in Lorette near Québec City, he may have belonged to the La Colonelle company, which was stationed in Québec. Both companies arrived on the same ship and participated in many of the same military activities.]

Upon their arrival in the summer of 1665, both the La Colonelle and Saurel companies were assigned to rebuild and garrison Fort Richelieu, a strategic site on the Richelieu River later renamed Fort de Saurel. In 1666, they participated in a major French expedition into Mohawk territory, helping to destroy several villages and food supplies in an effort to force peace. The campaign was successful, and by 1667, the Iroquois Confederacy had agreed to peace terms. With hostilities ending, many soldiers were offered land in exchange for remaining in the colony.

Plan of Fort Richelieu, 1695 (Wikimedia Commons)

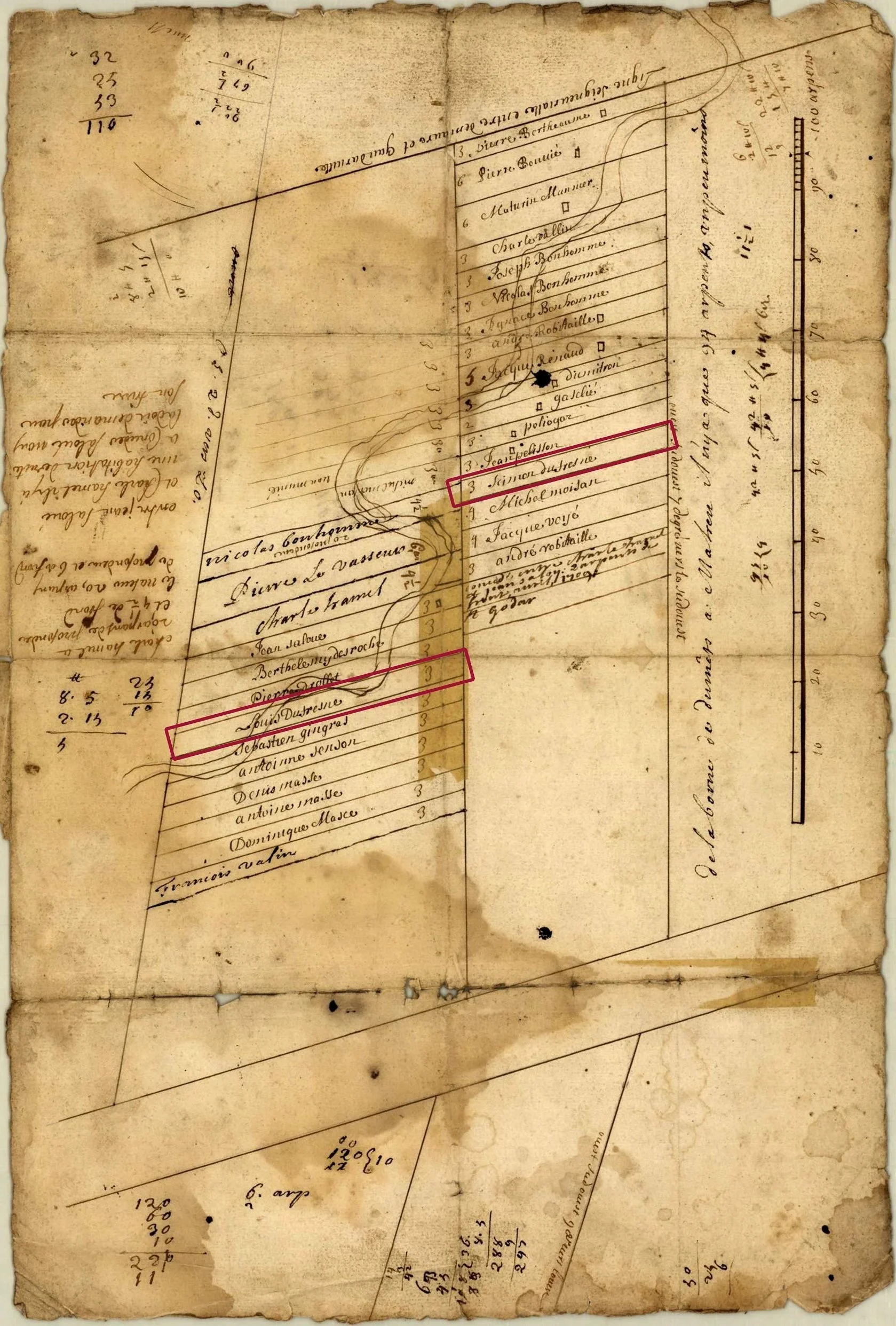

Land at Côte Champigny

On April 28, 1669, Julien received a land concession in the seigneurie of Gaudarville. The lot on côte Champigny measured three arpents of frontage by twenty arpents in depth. It bordered the lands of Gervais Bisson and Henri Larchevêque, the road called Champigny, and another road running parallel to it. Julien promised to clear and cultivate the land and to settle there himself (or have someone do so on his behalf). The seigneurial rente was 60 sols and two live capons annually, plus two deniers in cens.

[Today, Julien’s land would be located in the western part of Québec City, probably on the border between the Champigny sector (Sainte-Foy–Sillery–Cap-Rouge borough) and the territory of L'Ancienne-Lorette, near the Cap Rouge River.]

Survey map of two rows of the lands located at the seigneurial line between Maur and Gaudarville, showing the lands owned by Julien’s sons Simon and Louis (map drawn between 1692 and 1725, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Marguerite Berrin, Fille du Roi

Marguerite Berrin, daughter of merchant Pierre Berrin and Louise Anblard (or Anblart), was born around 1655 in the parish of Saint-Jean-en-Grève in Paris, France.

The Church of Saint-Jean-en-Grève, established by the 9th century and located near today’s Hôtel de Ville in Paris, served as a parish church for the city’s mercantile and artisan population. Rebuilt in the Gothic style between the 13th and 15th centuries, it featured a square bell tower and vaulted interior, reflecting the growing prominence of the district it served. Throughout the early modern period, the church played a central role in the civic and spiritual life of the Grève quarter. Suppressed during the French Revolution, it was deconsecrated in 1790 and demolished in 1797, leaving no physical trace.

View of Saint-Landry Bridge in Paris, with the church of Saint-Jean-en-Grève in the background (1657 engraving by Israël Silvestre, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

In 1672, following the death of her father, Marguerite left her home country in search of a new life in New France. A Fille du roi, she brought with her a dowry of goods valued at about 700 livres—considerably higher than that of the average Fille du roi.

Marguerite initially settled in Québec. On June 24, 1673, she gave birth to a son born out of wedlock, named Jean Baptiste. The child’s father was Simon François Daumont de Saint-Lusson, a French military officer and explorer best known for his symbolic act of claiming the interior of North America for France.

Marriage and Family

On the afternoon of June 24, 1675, notary Romain Becquet drew up a marriage contract between Julien Bouin dit Dufresne and Marguerite Berrin in his office in Québec. Julien was 35 years old, and Marguerite was about 20. Julien was recorded as an habitant living at Champigny, in the seigneurie of Gaudarville, originally from the parish of Saint-Pierre in Ancenis. [Montrelais is located about 13 kilometres east of Ancenis; Julien likely gave Ancenis as his place of origin because he had lived there before emigrating to Canada or because it was a more recognizable locality in the area.] Marguerite was recorded as a resident of Québec, originally from the parish of Saint-Jean-en-Grève in Paris.

The contract followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. The customary dower was set at 300 livres, and the préciput at 200 livres. Marguerite brought merchandise valued at 700 livres, half of which was to be included in their communauté de biens (community of goods). Julien agreed to provide for Marguerite’s two-year-old son, Jean Baptiste, until the age of 15. Neither party could sign the marriage contract.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children.

The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him. The preciput, under the regime of community of property, was a benefit conferred by the marriage contract, usually on the surviving spouse, granting them the right to claim a specified sum of money or property from the community before the rest was divided.

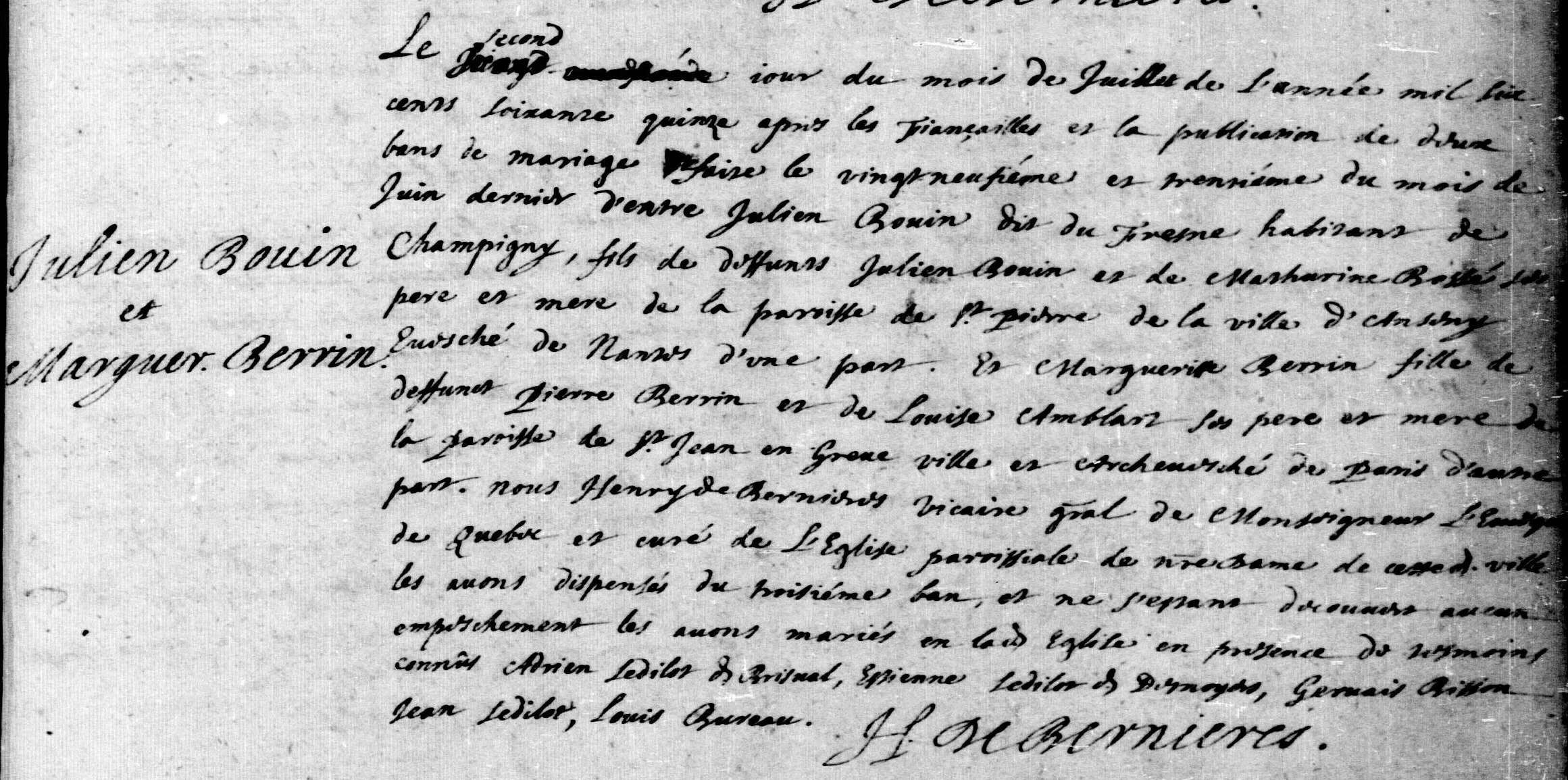

The couple was married on July 2, 1675, in the parish of Notre-Dame in Québec. Witnesses included Adrien Sédilot dit Brisval, Étienne Sédilot dit Desnoyers, Gervais Bisson, Jean Sédilot, and Louis Bureau.

1675 Marriage of Julien Bouin dit Dufresne and Marguerite Berrin (Généalogie Québec)

Julien and Marguerite settled in L'Ancienne-Lorette and had one son:

Charles François (1676–1746)

Death of Marguerite Berrin

The details of Marguerite Berrin’s death are unknown. She died sometime between the birth of her last child on May 13, 1676, and April 5, 1679. On the latter date, five-year-old Jean Baptiste was given up for adoption to Vincent Poirier, militia captain for côte Saint-Michel. Julien declared that he did not have the means to care for the child. The agreement was drawn up by notary Romain Becquet.

In the 1681 census of New France, Julien and his son Charles François were recorded as living in the seigneurie of Gaudarville. Julien held twelve arpents of cleared land but owned no livestock or firearms.

1681 census of New France for Julien and Charles “Boin” (Library and Archives Canada)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

Julien’s Second Marriage

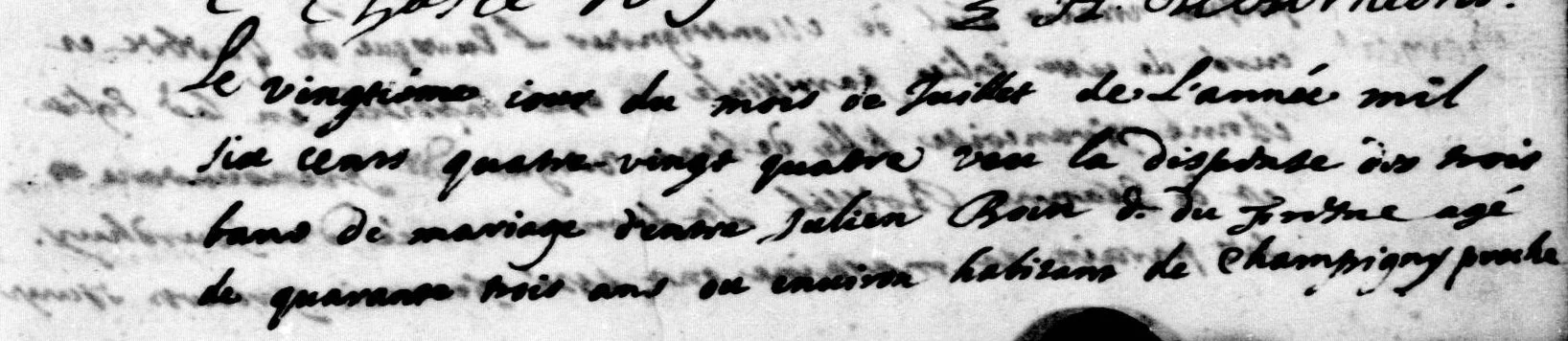

On the afternoon of July 16, 1684, notary Gilles Rageot drew up a marriage contract between Julien and Jeanne Rivaud. Julien was recorded as an habitant of côte Champigny, a parishioner of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, and the widower of Marguerite Berrin. Jeanne was recorded as the daughter of Pierre Rivaud and Marie Quequejeu (sometimes spelled Quelquejeu). The contract did not mention that she was also the widow of Pierre Dorais. Julien was 44 years old; Jeanne was only 15.

Julien contributed his land to the community of goods: a concession in the seigneurie of Gaudarville at côte Champigny, measuring three arpents of frontage by twenty arpents in depth, with a house and shed. Eight of the arpents were arable, six or seven had been cleared by pickaxe, and the remainder was still wooded.

The couple was married four days later, on July 20, 1684, in the parish of Notre-Dame in Québec.

1684 Marriage of Julien Bouin dit Dufresne and Marie Jeanne Rivaud (Généalogie Québec)

The Controversial Deaths of Jeanne’s Husband and Mother

In May 1684, Pierre Dorais and his mother-in-law, Marie Quequejeu, were accused of incest in Quebec City—one of the most serious moral and legal crimes in New France. Quequejeu, a former Fille du roi and widow, had lost her husband in 1681 and soon after married her eldest daughter Jeanne, then just 13, to Dorais, a fur trader in his 30s. Three years later, rumours circulated that Marie and Pierre were having a sexual relationship, and some accounts even alleged that Marie had borne and killed an infant from the affair. Although never formally charged with infanticide, both were condemned to death for incest.

Rather than bringing the case before the Sovereign Council—the proper legal authority—Intendant Jacques de Meulles handled the matter himself, bypassing standard judicial procedure. On May 13, 1684, he found them guilty and ordered their execution the very next day. There was no trial transcript, no recorded witness testimony, and no chance for appeal. Surviving documentation shows they were executed “par ordre de justice,” likely by hanging, and then buried in parish cemeteries.

1684 burials of Marie Quequejeu and Pierre Dorais (Généalogie Québec)

The case raised serious concerns at the time. Attorney General Denis-Joseph Ruette d’Auteuil complained to the French crown that de Meulles had overstepped his authority by judging and executing the accused without due process. The French minister, Seignelay, reprimanded the intendant for acting without jurisdiction and forbade such actions in future. While the truth of the incest allegation remains uncertain—no formal evidence survives—the case became infamous as an example of judicial overreach and the dangerous blending of moral panic with unchecked legal power in colonial New France.

Jeanne’s Remarriage

At just 15 years old, Jeanne Rivaud became a widow following the execution of her husband in May 1684. In the tight-knit and precarious society of New France, her youth—combined with the scandal surrounding her family—left her socially and economically vulnerable. Within two months, she remarried. Julien Bouin dit Dufresne, a 44-year-old former soldier and habitant, became her second husband. While the age disparity—over three decades—may seem extraordinary today, in the colonial context it was a pragmatic match: Julien offered stability, resources, and an opportunity for Jeanne to rebuild her standing in the community. The swift remarriage aligned with social norms of the time, which encouraged young widows to remarry promptly.

Julien and Jeanne settled in L’Ancienne-Lorette and had four children:

Simon (ca. 1687–1724)

Marie Renée (1690–1706)

Louis (ca. 1693–1743)

Claude (1696–?)

[Following her second marriage, Jeanne appears under a different surname in some records: Beaubry, Beaudry, or Gaudry. The origin of this name is unknown; it may reflect an attempt to leave behind her previous identity.]

Deaths of Jeanne and Julien

Jeanne Rivaud died sometime between the birth of her last child and May 8, 1710, when she is recorded as deceased in a notarial record. On that date, notary Jean-Étienne Dubreuil drew up a land-sharing agreement between Julien and his son Charles François. The document notes that an earlier agreement had been made following the death of Marguerite Berrin, recorded by the priest of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, but that the original document had been lost. Julien and Charles François had agreed to divide the land equally. Charles François, having invested significantly in his portion—including constructing buildings—sought to formalize the terms of the lost agreement.

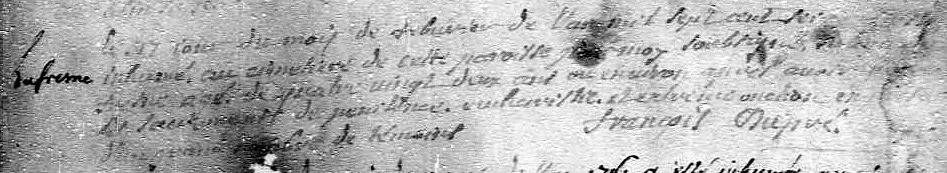

Julien Bouin dit Dufresne died at the age of 75. He was buried on February 17, 1716, in the parish cemetery of Notre-Dame-de-l’Annonciation in L’Ancienne-Lorette, “in the presence of numerous witnesses.” [The burial record erroneously states that he was about 82 years old.]

1716 burial of Julien Bouin dit Dufresne (Généalogie Québec)

The lives of Julien Bouin dit Dufresne and Marguerite Berrin reflect the social and demographic ambitions of New France in the 17th century. Julien, a former soldier in the Carignan-Salières Regiment, and Marguerite, a Paris-born Fille du roi, embodied the colonial project of settlement through land, marriage, and family. Though their union was brief—cut short by Marguerite’s early death—it laid the foundation for a lasting legacy. Their son, Charles François, carried the family name into future generations, while their story endures as a testament to the challenges and resilience of early French colonial life.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Montrelais (Saint-Pierre) B 1611(février)-1648(janvier)," digital images, Archives départementales de Loire-Atlantique (https://archives-numerisees.loire-atlantique.fr/v2/ark:/42067/1b40f62fd131ed205c25e87a658e49f0 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), baptism of Julien Bouin, 20 Mar 1640, Montrelais (St-Pierre), image 96 of 165.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/58918 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), baptism of Jean Baptiste Daumont, 24 Jun 1673, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/67134 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), marriage of Julien Bouin Dufresne and Marguerite Berrin, 2 Jul 1675, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/67273 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), marriage of Julien Boin Dufresne and Jeanne Rivault, 20 Jul 1684, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/69459 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), burial of Marie Quequejeu (and Pierre Doret; same page), 14 May 1684, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/79045 : accessed 7 Aug 2025), burial of Julien Dufresne, 17 Feb 1716, L'Ancienne-Lorette (Notre-Dame-de-L’Annonciation).

"Seigneurie de Gaudarville et seigneurie de Fossambault - Registre des titres de concessions," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/archives/52327/4751987?docref=R-1Gd2jwaAuDIfvuXZ9odw : accessed 26 Aug 2025), land concession to Jullien Bouin, 28 Apr 1669, images 149-150 of 420.

"Actes de notaire, 1665-1682 // Romain Becquet," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064892?docref=-6rOIoWQcB9NdEALeBEvCA : accessed 6 Aug 2025), marriage contract of Julien Bouin and Marguerite Berrin, 24 Jun 1675, images 901-902 of 954.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064894?docref=E1PuX0SEODo1XkEtQwYHtQ : accessed 6 Aug 2025), adoption of Jean Baptiste Daumont, 5 Apr 1679, image 247 of 1,105.

"Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 // Gilles Rageot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3NF-49NX-S?cat=1171570&i=541&lang=en : accessed 6 Aug 2025), marriage contract of Julien Bouin and Jeanne Rivaud, 16 Jul 1684, images 542-543 of 1,327; citing orignal data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1708-1739 // Jean-Etienne Dubreuil," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LC-HPVK?cat=746806&i=206&lang=en : accessed 7 Aug 2025), land sharing agreement between Julien Bouin and Charles Bouin, 8 May 1710, images 207-209 of 2,988; citing orignal data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), household of Julien Boin, 14 Nov 1681, Seigneurie de Godarville, page 52 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/bouin/-dufresne : accessed 6 Aug 2025), entry for Julien Bouin / Dufresne (person 240506), updated on 16 Jan 2017.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/4418 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Julien BOUIN DUFRESNE and Marguerite BERRIN, union 4418.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/5449 : accessed 6 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Julien BOUIN DUFRESNE and Marie Jeanne RIVAUD, union 5449.

Peter Gagné, Kings Daughters & Founding Mothers: the Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, Volume One (Orange Park, Florida : Quintin Publications, 2001), 87.

Jack Verney, The Good Regiment: The Carignan-Salières Regiment in Canada, 1665–1668 (Montréal : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991), 183.

Jean-Guy Pelletier, “SAUREL, PIERRE DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saurel_pierre_de_1E.html : accessed 6 Aug 2025), University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.

Mona Rainville, "La triste fin de Marie Quelquejeu, fille du roi," Mémoires de la Société généalogique canadienne-française, volume 65, number 4, pages 323-325.