Jean Perrier dit Lafleur & Marie Gaillard

Discover the remarkable journey of a 17th-century French soldier and a Fille du roi who helped build early Canada—from military campaigns in the Caribbean to family life in Beauport and Ville-Marie. Explore their migration, marriage, and legacy in New France.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jean Perrier dit Lafleur & Marie Gaillard

A Soldier of the Caribbean and a Fille du roi from Normandy

Jean Perrier dit Lafleur, the son of Jean Perrier (or Poirier) and Marie Dervié, was born around 1646 in Pau, Béarn, France. Located in southwestern France in the department of Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Pau is situated just 50 kilometres north of the Spanish border. As of 2022, it had a population of about 79,000 residents, known as Palois. [Though Jean was occasionally called Jean Baptiste, he usually went by Jean.]

Location of Pau in France (Mapcarta)

In the 17th century, Pau was the capital of the historical province of Béarn, a semi-autonomous region annexed by the French crown in 1620 under Louis XIII. Though no longer a sovereign principality, Pau remained an important administrative and military centre in the southwest. Its location near the Pyrenees gave it strategic importance in monitoring the Spanish border, particularly during periods of tension such as the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659).

Jean worked as a maître-tisserand (master weaver).

By 1664, the year Jean left France, Pau had been fully integrated into the French kingdom but retained a distinct regional identity shaped by its Béarnais culture, language, and legal traditions.

Pau, circa 1905–1910 postcard (Geneanet)

Pau, circa 1912 postcard (Geneanet)

Pau, circa 1902–1905 postcard (Geneanet)

Château de Pau, circa 1900–1908 postcard (Geneanet)

Military Expedition to the Caribbean

Although his enlistment date is uncertain, Jean was recruited as an infantry soldier in the French army under Captain Vincent de la Brisardière of Orléans. The La Brisardière Company was initially part of the Régiment d’Orléans, but in 1663–1664, it became one of four detached companies selected to serve under Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy, the newly appointed Lieutenant-General of French America. The other three companies were Berthier, La Durantaye, and Monteil. This is likely when Jean acquired his dit name, Lafleur.

In early 1664, Tracy embarked on a military expedition to the West Indies and South America. The flotilla of four companies, including the La Brisardière Company, departed from the port of La Rochelle on February 26, 1664. Also on board were 650 settlers for South America. The expedition’s objectives were to expel the Dutch from French Guiana and secure French interests in the Caribbean.

In May 1664, the ships landed in Cayenne (capital of modern-day French Guiana) and captured the city without much resistance from the Dutch. The French re-established control in the region, and many of the 650 colonists disembarked and settled in Cayenne. Wanting to “drive the Dutch out of the West Indies,” Tracy installed loyal governors in Martinique, Tortuga (Hispaniola), Guadeloupe, Grenada, and Marie-Galante. The four companies remained in the Caribbean for several months, overwintering in Guadeloupe. During this time, the troops repelled any English or Dutch threats in the region.

The Islands of the Caribbean, 1722 map (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

By April 1665, Tracy considered his mission accomplished and received new orders: sail to New France. That spring, he and his four companies sailed north aboard Le Brézé.

Tracy was instructed to assist the Carignan-Salières Regiment, a French military unit dispatched to New France in 1665 to bolster the colony’s defences against the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, whom the French called the Iroquois. While the core Carignan-Salières Regiment comprised 20 companies, Tracy’s four additional companies joined the expedition and were integrated into its operations upon arrival in New France.

A Soldier in New France

Because of its size, Le Brézé could not sail directly to Québec. It anchored at Percé, on the eastern tip of the Gaspé peninsula, and the soldiers were transferred to smaller boats. Tracy’s flotilla finally arrived at Québec on June 30, 1665.

“Officer and soldiers of the régiment de Carignan-Salières, 1665-1668," drawing by Francis Back. “The common soldiers at left and right carry muskets. Hanging from their shoulder belts are the powder flasks known as 'the Twelve Apostles.' The officer at centre carries a half-pike and wears the white sash of a French officer around his waist.” (Canadian Military History Gateway)

Soon after arrival, the La Brisardière Company continued up the St. Lawrence and took part in constructing a series of forts along the Richelieu River, a strategic initiative aimed at curbing Iroquois incursions. Soldiers built three forts in 1665—Fort Sainte-Thérèse, Fort Saint-Louis de Chambly, and Fort Sorel—and another in 1666: Fort Sainte-Anne on Lake Champlain. These fortifications played a crucial role in securing the colony’s southern frontier.

1666 map of the forts constructed by the Carignan-Salières Regiment on the Richelieu River ("Plans des forts faicts par le regiment Carignan Salieres sur la riviere de Richelieu dicte autrement des Iroquois en la Nouvelle France"), map by François Le Mercier (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In the 1666 census of New France, taken during the winter of 1665–1666, Jean appeared not as a soldier but as an engagé domestique (domestic servant), living in the household of Jean Nault in the census division of Saint-Jean, Saint-François, and Saint-Michel, near Québec. This was not unusual for members of the Carignan-Salières Regiment. Following their arrival in 1665, many soldiers were billeted with colonists due to a lack of military accommodations. During this period of relative peace, they often assisted with household or agricultural tasks while remaining under military authority. The census recorded individuals based on their role within the household at the time, rather than their formal military status. His later inclusion in the 1668 roll of soldiers who chose to remain in the colony confirms his continued connection to the regiment and his transition from soldier to settler. Jean did not appear in the 1667 census, likely because he was on active military duty.

1666 census of New France for the household of Jean “Neau” (Library and Archives Canada)

Perrier or Poirier?

Jean’s surname appeared as Poirier in the 1666 census and in his 1669 marriage contract and record. In all other known instances, his name was recorded as Perrier, or a phonetic variation. His descendants adopted the name Perrier, rather than Poirier or his dit name, Lafleur. Jean could not write or sign his name, which may have led some clerks to record it incorrectly.

The French launched expeditions to subdue the Iroquois, who had been attacking settlers and Indigenous allies in New France. The La Brisardière Company took part in several incursions into Iroquois territory (in present-day New York state) under Tracy’s command. In the summer and autumn of 1666, French soldiers marched south toward Mohawk lands. The La Brisardière Company was likely among those who advanced into the Mohawk heartland in October 1666. The force razed four evacuated Mohawk villages and destroyed their winter food supplies. These efforts dealt a significant blow to the Iroquois, forcing them to consider peace negotiations.

On July 10, 1667, peace was declared between the French and the Five Nations of the Iroquois. The truce would last for 18 years. Once peace was established, Carignan-Salières soldiers were given the choice to return to France or remain in the colony. Authorities offered incentives to those who stayed, including land grants along the St. Lawrence River and marriages to Filles du roi.

“Roll of the Soldiers of the Regiment of Carignan Salière who became inhabitants of Canada in 1668" (Library and Archives Canada)

Of the 1,200 to 1,300 Carignan-Salières soldiers who arrived in New France, including Tracy’s troops, approximately 350 died, about 350 returned to France in 1668, and at least 446 chose to remain. An additional 100 continued serving in the colony’s military. The decision to settle was likely economic—the opportunity to own land and establish a household was not typically available to men of the lower classes in France.

Jean was one of only three soldiers from the La Brisardière Company to remain in New France.

Settlement in New France

On December 10, 1668, Jean received his first land concession from seigneur Joseph Giffard. Located “on a line separating the village of Saint-Joseph from the village of Saint-Michel in the seigneurie of Beauport,” the land measured two arpents of frontage. Jean agreed to pay 50 sols in seigneurial rente annually on each feast day of Saint-Martin in November, plus one sol in cens per arpent of frontage, as well as two live capons. He also agreed to have his grain ground at the seigneurial mill.

Jean’s 1668 land concession (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Marie Gaillard (or Daire), daughter of Pierre Gaillard (or Daire) and Marie Gaillard (or Martin), was born around 1647 in Ernemont, Normandy, France—present-day Ernemont-sur-Buchy in the Seine-Maritime department. Located about 17 kilometres northeast of Rouen, the rural commune of Ernemont-sur-Buchy has a population of fewer than 300 residents, known as Ernemontois.

Gaillard or Daire?

The confusion around Marie’s surname stems from her marriage contracts and records. At her first marriage, she is identified as Marie Daire, daughter of Pierre Daire and Marie Gaillard. In all other records following this wedding, she is called Marie Gaillard. On her second marriage contract, her parents are listed as Pierre Gaillard and Marie Martin. Her French baptism record has not been found, which would clarify her surname at birth.

"The Arrival of the French Girls at Quebec," watercolour by Charles W. Jefferys (Wikimedia Commons)

Life in Ernemont during the 17th century was predominantly agrarian. Residents engaged in farming, animal husbandry, and local crafts. The village's proximity to Rouen, a significant urban centre, provided opportunities for trade and access to broader markets. Social and economic activities were closely tied to the rhythms of the agricultural calendar and the observance of religious festivals.

After the death of her father, Marie left her homeland for New France, arriving in 1669 as a Fille du roi, likely aboard the Saint-Jean-Baptiste on June 30, 1669.

Marriage and Family

On September 22, 1669, notary Romain Becquet drafted a marriage contract between Jean “Poirier,” an habitant from the côte de Beauport, and newly arrived Fille du roi Marie “Daire.” He was about 23 years old; she was about 22. The contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. Jean endowed his future bride with a prefix dower of 300 livres. For her part, Marie brought with her goods valued at approximately 200 livres, which were added to the community of goods. Neither was able to sign the contract.

Jean and Marie were married on October 6, 1669, in the parish of Notre-Dame in Québec. Marie is described as being from “the parish of Clermont Sainte Croix in the archbishopric of Rouen.” [The PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique) believes that this location refers to Ernemont.]

1669 marriage of Jean and Marie (Généalogie Québec)

The couple settled on Jean’s land in Beauport, where they had at least six children:

Marie (1670–1740), twin

Marie Marthe (1670–1750), twin

Jacques (1672–1737), became a voyageur and a militia captain

Marie Madeleine Josèphe (1674–aft. 1740)

Marie Marguerite (ca. 1677–1755)

François Madeleine (1680–aft. 1704), became a voyageur and settled in Mobile (Alabama)

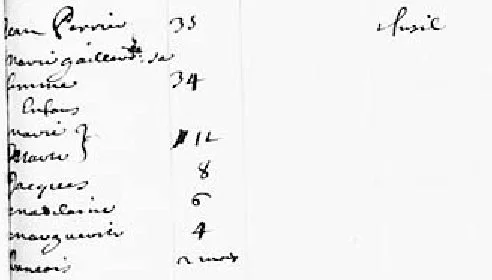

1681 census of New France for the Perrier family (Library and Archives Canada)

On November 20, 1671, Jean and Marie sold their two-arpent land concession to Michel Accos. This was the land Jean had received from seigneur Giffard in 1668. They were recorded as residents of the “village of Saint-Michel on the côte and seigneurie of Beauport.” In exchange, Accos agreed to pay 80 livres in cash, five livres in pots-de-vin (wine), and one pair of French shoes.

On October 23, 1675, Jean leased a plot of farmland located in Petite-Rivière [on the Saint-Charles River] from master surgeon Timothée Roussel for five years, in return for half of the grain yield.

Jean and Marie were enumerated in the 1681 census of New France, living in Beauport with their six children. The family owned one gun but no land under cultivation or animals.

Death of Jean Perrier

Jean Perrier died at about 35 years of age, sometime between November 14, 1681 (the date of the census), and September 22, 1682 (the date of Marie’s second marriage). His burial record has not been found.

Widowhood and Remarriage

In the challenging environment of New France, marriages lasting more than 20 years were uncommon. Upon the death of a spouse, it was essential for the surviving partner to remarry promptly. Most families were large, making the task of raising children alone particularly daunting. Widows faced greater difficulty in finding a new husband compared to widowers. They typically had many children and limited financial resources, which made remarriage more challenging. The likelihood of a widow remarrying increased with her youth. On average, widows remarried within three years, whereas widowers typically found new spouses within two years. In the colony’s earliest days, the timeline was shorter: before 1680, about half of all widows and widowers remarried within a year of their spouse’s death.

Marie’s Second Marriage

Marie married ploughman Jean Sabourin on September 22, 1682, in Beauport. Both were widowed with children. Marie was about 35 years old; Jean about 41. They did not have any children together; rather, they merged his surviving five with her surviving six children.

On September 27, 1684, Marie and Jean decided to formalize their legal affairs. Two years after their wedding, notary Paul Vachon drew up their marriage contract. Once again, the contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. Jean endowed Marie with a dower of 500 livres. The préciput was set at 200 livres. [The préciput, under the regime of community of property between spouses, was an advantage conferred by the marriage contract on one of the spouses—generally the survivor—granting the right to claim, before any division of property, specific goods or a sum of money from the common estate.] Neither was able to sign the contract.

Around 1683, Marie and Jean relocated westward to the Montréal area. There, their families became further intertwined when Marie’s daughter Madeleine, then 14 years old, married her stepbrother Pierre Sabourin, approximately 22, on 24 May 1688 in the parish of Notre-Dame in Montréal.

Over the next two and a half decades, Marie and Jean were involved in several real estate transactions, all recorded by notary Antoine Adhémar de Saint-Martin:

August 16, 1688: Marie and Jean purchased a plot of land on the island of Montreal, at Rivière Saint-Pierre, from Barbe Lefebvre, the widow of Mathurin Goyer. The land measured three arpents of frontage by twenty arpents deep. The couple agreed to pay ten livres in cash and twelve minots of wheat. They were recorded as residents of the town of Villemarie. [A minot was a unit once used for dry matter (seeds and flour), equal to half of a mine. A mine corresponded to approximately 78.73 litres.]

December 14, 1688: Marie and Jean received a land concession on the island of Montreal, at Rivière Saint-Pierre, from the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Montréal, seigneur of the island. The land measured three arpents of frontage by twenty arpents deep. They were recorded as residents of the island of Montreal.

September 25, 1690: Marie and Jean surrendered the land they had received from the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice de Montréal two years earlier. They were recorded as residents of the town of Villemarie.

August 6, 1694: Marie and Jean purchased a land concession from René Drouillard, a ship’s carpenter, for 50 livres in cash. The land was located below the hillside that ran along Lac Saint-Pierre, in the seigneurie of the island of Montreal. It measured three arpents of frontage by twenty arpents deep. They were recorded as residents of Rivière Saint-Pierre.

October 10, 1695: Marie and Jean sold the plot of land they had purchased the previous year to Honoré Dasny [Danis] for 72 livres and ten sols. They were recorded as residents of Rivière Saint-Pierre.

August 12, 1709: Marie and Jean leased a plot of land from the religious nuns of the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. The land, which included a house, measured four arpents of frontage and formed part of the domaine Saint-Jouachin [Joachim]. In exchange, the couple agreed to clear at least two wooded arpents of land per year by plough.

Rivière Saint-Pierre and Lac Saint-Pierre

In the 17th century, Rivière Saint-Pierre and Lac Saint-Pierre were waterways on the island of Montreal that have since largely disappeared due to urban development. Rivière Saint-Pierre was a small river that ran from the centre of the island to the St. Lawrence River, flowing near the early settlement of Ville-Marie (the birthplace of Montreal) and emptying near present-day Verdun or Pointe-Saint-Charles. It served as an important geographic marker in early land concessions and is visible on old maps, such as those shown below.

Lac Saint-Pierre referred to a small widening of the same river further west on the island of Montreal. In land transactions, “below the hillside that ran along Lac Saint-Pierre” likely refers to terrain sloping toward the mouth or broader section of the Rivière Saint-Pierre, which influenced settlement patterns in the area.

Montreal from 1645 to 1652 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Plan of part of the isle of Montreal, circa 1720-1730 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Deaths of Marie Gaillard and Jean Sabourin

Until their deaths, Marie and Jean disappear from the public record.

Jean Sabourin died at about 80 years of age. He was buried on September 28, 1721, in the Saint-Joachim cemetery in Pointe-Claire.

Marie Gaillard died at about 89 years of age on July 12, 1736. She was buried the following day in the Saints-Anges cemetery in Lachine. Her burial record states that she was “about 93.”

1736 burial of Marie Gaillard (Généalogie Québec)

The story of Jean Perrier dit Lafleur and Marie Gaillard reflects the path taken by many pioneers who settled in New France in the 17th century. A soldier of the king turned colonist, Jean helped defend and build the territory, while Marie, a Fille du roi, embodied the vital role of women in establishing families in the colony. Together, they endured war, marriage, and loss, all while contributing to land development and the foundation of lasting communities.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/14270 : accessed 27 May 2025), marriage of Guillaume Loret and Marie Perrier [daughter of Jean, master weaver, and Marie Gaillard], 6 Dec 1683, Montréal, Lachine (Sts-Anges); citing original data : Collection Drouin, Institut généalogique Drouin.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66857 : accessed 27 May 2025), marriage of Jean Poirier and Marie Daire, 6 Oct 1669, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/77285 : accessed 27 May 2025), marriage of Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 22 Sep 1682, Beauport (Nativité-de-Notre-Dame).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/47527 : accessed 16 Jun 2025), marriage of Pierre Sabourin and Madeleine Perrier, 24 May 1688, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/15804 : accessed 28 May 2025), burial of Jean Baptiste Sabouren, 28 Sep 1721, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/116072 : accessed 28 May 2025), burial of Marie Gaillard, 13 Jul 1736, Montréal, Lachine (Sts-Anges).

Léopold Lamontagne, “PROUVILLE DE TRACY, ALEXANDRE DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prouville_de_tracy_alexandre_de_1E.html : accessed 28 May 2025), University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, revised 2019.

Kim Kujawski, "The Carignan-Salières Regiment," The French-Canadian Genealogist (https://www.tfcg.ca/carignan-salieres-regiment : accessed 27 May 2025).

“Rolle des Soldats du Regiment de Carignan Salière qui se sont faits habitans de Canada en 1668", digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/exploration-settlement/new-france-new-horizons/Documents/Warfare/rolle-soldats-carignansalieres-roll-soldiers.pdf : accessed 27 May 2025).

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 27 May 2025), household of Jean Nau, 1666, Saint-Jean, Saint-François and Saint Michel, page 100 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 27 May 2025), household of Jean Perrier, 14 Nov 1681, Beauport, page 268 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

“Archives de notaires : Paul Vachon (1655-1693)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4215635?docref=ahzklVz3T6TuZc-anrg7vQ : accessed 27 May 2025), land concession to Jean Perrier dit Lafleur by Joseph Giffard, 10 Dec 1668.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4215635?docref=6HJEtaGo_GNFstQ3sKWtxw : accessed 27 May 2025), sale of land concession by Jean Perier and Marie Gaillard to Michel Accos, 20 Nov 1671.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4215637 : accessed 27 May 2025), marriage contract between Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 27 Sep 1684.

“Archives de notaires : Romain Becquet (1665-1682)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064889?docref=WjMBNxoDidnpJP8tW2pz2g : accessed 27 May 2025), marriage contract between Jean Poirier and Marie Daire, 22 Sep 1669.

“Actes de notaire, 1668-1714 // Antoine Adhémar," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTS-633F-L?cat=541271&i=1516&lang=en : accessed 27 May 2025), sale of land by Barbe Lefebvre to Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 16 Aug 1688.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTS-63M7-3?cat=541271&i=1805&lang=en : accessed 27 May 2025), land concession by the Séminaire de St-Sulpice de Montréal to Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 14 Dec 1688.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-Y3Z5-Q?cat=541271&i=356&lang=en : accessed 27 May 2025), surrender of a land concession by Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard to the Séminaire de St-Sulpice de Montréal, 25 Sep 1690.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTH-579R-7?cat=541271&i=1934&lang=en : accessed 27 May 2025), sale of land by René Drouillard to Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 6 Aug 1694.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-MWN5-5?cat=541271&i=423&lang=en : accessed 27 May 2025), sale of land by Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard to Honoré Dasny, 10 Oct 1695.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-2B8Q?cat=541271&i=1262&lang=en : 27 May 2025), lease by the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal to Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 12 Aug 1709.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 27 May 2025), " Bail à ferme et loyer d'une terre située à la Petitte Riviere; par Timothée Roussel, maître chirurgien, de la ville de Québec, à Jean Perier dit Lafleur," notary G. Rageot, 23 Oct 1675 [original notarial record not found].

“Année 1669 : Le St Jean-Baptiste pour Québec," Migrations.fr [archived] (https://web.archive.org/web/20211209093228/http://www.migrations.fr/NAVIRES_LAROCHELLE/lestjeanbaptiste1669.htm : accessed 27 May 2025).

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/2848 : accessed 27 May 2025), dictionary entry for Jean PERRIER and Marie GAILLARD, union 2848.

André Lachance, Vivre, aimer et mourir en Nouvelle-France; Juger et punir en Nouvelle-France: la vie quotidienne aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Montréal, Québec: Éditions Libre Expression, 2004), 38-40.