Jacques Marchand & Françoise Capel

Discover the story of Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capel, early settlers of Batiscan 17th-century New France. From surviving Iroquois raids to building a family legacy on the banks of the St. Lawrence River, their history offers a glimpse into the lives of Québec’s first pioneers.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jacques Marchand & Françoise Capel

Pioneers of Batiscan: A Story of Survival and Legacy

Jacques Marchand was born around 1638 in France. His name has also been recorded as Marchant, Le Marchant, and Le Marchand. Although several sources claim he was born in Caen, Normandy, no document—French or Canadian—confirms his place of origin.

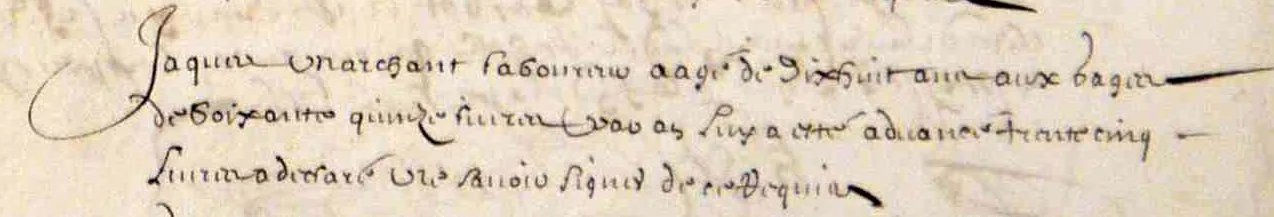

On April 11, 1656, 18-year-old Jacques agreed to a three-year engagement (work contract) in New France. He committed to work as a laboureur (ploughman) for merchant François Perron at a wage of 75 livres per year. He received 35 livres in advance wages. The contract, drafted by notary Abel Cherbonnier in La Rochelle, states that Jacques would sail aboard the ship Le Taureau alongside thirty other engagés hired by Perron to work in Canada. Jacques declared that he could not sign.

“Today, the eleventh of April, one thousand six hundred and fifty-six, all the persons named below appeared before Abel Cherbonnier, royal notary in the city and government of La Rochelle. They voluntarily acknowledged that they have agreed with François Peron, merchant of the said city, who is personally present, stipulating and accepting, that from the moment Peron requires or causes them to be required to embark on the ship named Le Taureau, belonging to the said Peron and of which Élie Tadourneau is the master, they will sail—subject to the perils of the sea [i.e., accidental loss or damage to the ship or cargo]—to Québec, in the country of Canada. Once in Québec or any other place in Canada, they will remain in the service, loyalty, and obedience of those whom Peron, or whoever carries out his orders, assigns to direct them.

Those with a trade will perform their trade, while those without one will carry out whatever work is assigned to them by those in charge. This service will last for three consecutive years, without interruption, starting from the day they set foot on land in Québec. They will receive the wages and salaries described below. Furthermore, their food will be provided during these three years, and they will not be charged for their passage or other expenses, which Peron has agreed to cover. To fulfill the above, without contravening it, they have pledged all their present and future goods and have renounced any claims contrary to these agreements. They have promised and sworn to uphold and keep this contract inviolably. By their own consent, they have been judged and condemned to this obligation by the said notary under proper submission. Done at La Rochelle, in the office of the notary, on the day and year above written.” [Translation based on the transcription of Guy Perron.]

Portion of 1656 contract specifying Jacques Marchand’s conditions (Archives départementales de Charente-Maritime)

Le Taureau departed from the harbour of Saint-Martin-de-Ré on April 11, 1656. While the ship’s exact arrival date in Canada is unknown, Jacques and the other passengers set foot on Canadian soil in the summer of 1656.

Location of Cesny-aux-Vignes in France (Mapcarta)

Françoise Capel, daughter of Julien Capel and Laurence Lecompte (or Le Conte), was born around 1626 in Cesny-aux-Vignes, Normandy, France. Located in the present-day department of Calvados, the rural commune lies about 200 kilometres west of Paris and has a current population of approximately 400 residents, called Cireniens. Her name has also been recorded as Capelle and Capelles in genealogical records.

A Fille à marier, Françoise likely arrived in Canada around 1650.

At the Convent

Shortly after her arrival in Québec, Françoise entered the Ursuline Convent, taking the name Soeur Saint-Michel as a postulante. [A postulante is a candidate for religious life in a convent, undergoing an initial probationary period before entering the novitiate. It is the first formal step on the path to becoming a nun.] Tragedy struck on December 30, 1650, when the convent was completely destroyed by a fire that started in the bakery.

“The first Ursuline monastery in Quebec,” 1840 painting by Joseph Légaré at the Musée des Ursulines de Québec (©The French-Canadian Genealogist)

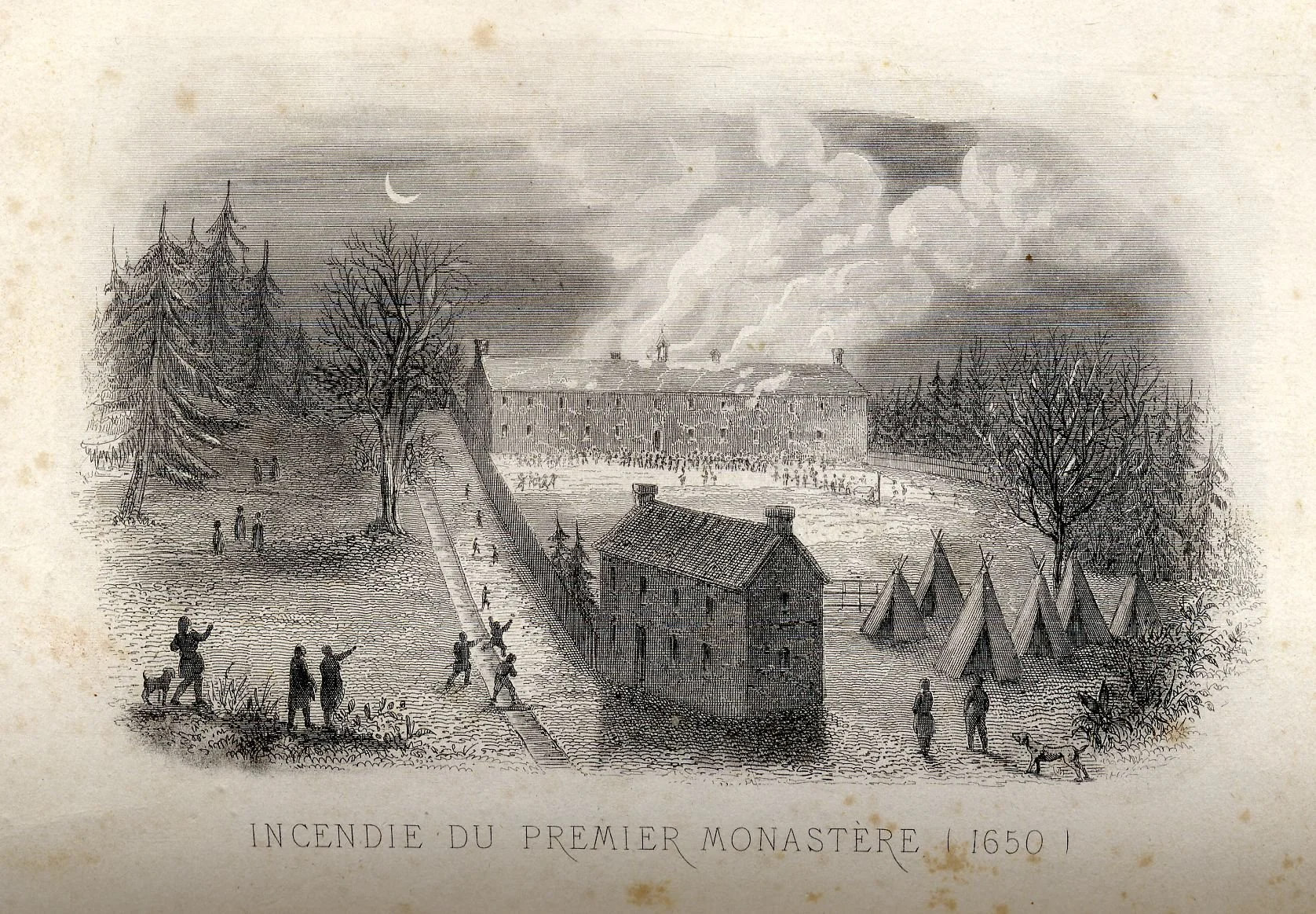

“Fire at the first monastery (1650),” 1864 drawing (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In the foreground of both images is the house of Madame de La Peltrie, where Françoise and nine other women lived after the fire.

According to the Relation des Jésuites:

“The Ursuline Mothers were visited by God through the fire that destroyed their house on the 30th of December, around two o’clock in the morning. The fire, which started in their bakery, had almost completely engulfed the upper part of the house before they even realized it. It was a great mercy that they managed to escape the flames and flee into the snow. It is almost a miracle that their little boarding students, both Indigenous and French, were not burned. […]

Their entire monastery was consumed in less than an hour, and they were unable to save anything except a few items from the sacristy. In that moment, these good Mothers found themselves truly living out their vow of poverty—but in a way that delighted the heart of God. The fire had made a complete holocaust of their clothing, their house, all their furniture, and even the alms and supplies that had been accumulated over more than ten years to help ease some of their needs. […]

After the disaster, they took refuge in a small house with only two rooms, which served as a dormitory, dining room, kitchen, living room, infirmary, and everything else for their entire community of thirteen people, along with some boarders whom their charity could not abandon—despite the almost unbearable hardships they had to endure, especially during the suffocating heat of the summer. Their poverty became so extreme that they lacked everything and were in need of all things.”

Some researchers have speculated that Françoise Capel was the person responsible for the fire, said to have been started by a “conversant novice sister.” This sister, working in the bakery that night, accidentally left hot embers in the breadbox, forgetting to remove them before going to bed. The convent had no conversant novices, so the term may have referred to someone who left the order before becoming a nun. Françoise did indeed leave the convent several months after the fire.

Françoise’s First Marriage

At the age of about 25, Françoise agreed to marry Jean Turcot. The couple had their marriage contract drawn up under private seign (not written by a notary) by a man named Leneuf on April 25, 1651. [The contract no longer exists.] The date of their wedding ceremony is unknown, but marriages usually took place within three weeks of the contract.

The couple had one son, Jacques, who was baptized in Trois-Rivières on September 4, 1652. The marriage was short-lived, and Jacques may have been born posthumously. On August 19, 1652, Jean Turcot was captured by the Iroquois and never seen again.

According to the Relation des Jésuites:

“On August 18, four inhabitants of Trois-Rivières, having gone a little below the French settlement, were pursued by the Iroquois, who, it is said, killed two of them and took the other two away to sacrifice them to their rage.

On August 19, the defeat was even greater. Monsieur du Plessis Kerbodot, Governor of Trois-Rivières, took with him forty or fifty Frenchmen and ten or twelve Indigenous allies. They boarded boats to pursue the enemy and, if possible, recover the prisoners and the livestock believed to have been taken. Having travelled about two leagues upstream from the fort, they spotted the enemy in the thickets at the edge of the woods. The governor disembarked in a place full of mud and highly disadvantageous. Someone pointed out the advantage the enemy had, since they could retreat into the forest. But he pressed on, advancing headlong. His bravery cost him his life, as well as the lives of fifteen Frenchmen. During this combat, some Iroquois who had separated from the main group killed a poor Huron and his wife, who were working in their field not far from the French dwellings.

God, who balances victories and sets their limits, showed in this disaster that He intended to preserve us: for if the Iroquois had fully exploited their advantage—as fear had overtaken our people after they lost their leader—they might well have shaken the settlers of Trois-Rivières. But they withdrew, as if they did not know how to take advantage of their victory and left the French to finish harvesting their crops in peace, though not without sorrow.

On August 23, they went to visit the site of the battle and found these words written on an Iroquois shield: ‘Normanville, Francheville, Poisson, la Palme, Turgot, Chaillou, S. Germain, Onnejochronnons and Agnechronnons. I have lost only a fingernail so far.’ Normanville, a young, skilled, and brave man who spoke both the Algonquin and Iroquois languages, had written these words with a piece of charcoal. He meant to indicate that the seven persons whose names were written there had been taken by the Iroquois, called Onnejochronnons and Agnechronnons, and that he himself had not yet suffered anything worse than having a fingernail torn out.”

Françoise’s Second Marriage

On November 9, 1653, notary Séverin Ameau drew up a marriage contract between the widowed Françoise and Jacques Lucas dit Lépine, an habitant of Cap-de-la-Madeleine. Jacques’s witnesses were Pierre Boucher (commanding captain of Trois-Rivières), Nicolas Rivard dit Lavigne (captain at Cap-de-la-Madeleine), Élie Bourbaut (notary at Cap-de-la-Madeleine), and Bertrand Fafard dit Laframboise (habitant of Trois-Rivières). Françoise’s witnesses were Michel Leneuf (who possibly drafted her first marriage contract), Jacques Brisson, and Jacques Bri[teau?] (habitant of Trois-Rivières). The contract followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. Françoise’s new husband agreed to treat her son Jacques Turcot as his own son for purposes of inheritance. Neither the bride nor groom could sign the contract.

The marriage record for Françoise and Jacques no longer exists. The couple had two children, Marie and François, both baptized in Trois-Rivières.

Unfortunately, Françoise’s second husband met the same fate as her first. On September 12, 1659, the Journal des Jésuites reported:

“A Frenchman named L'Épine was killed at Trois-Rivières by the Iroquois, perhaps by one of the two who had escaped from the prisons of Québec, one of whom has since been recaptured.”

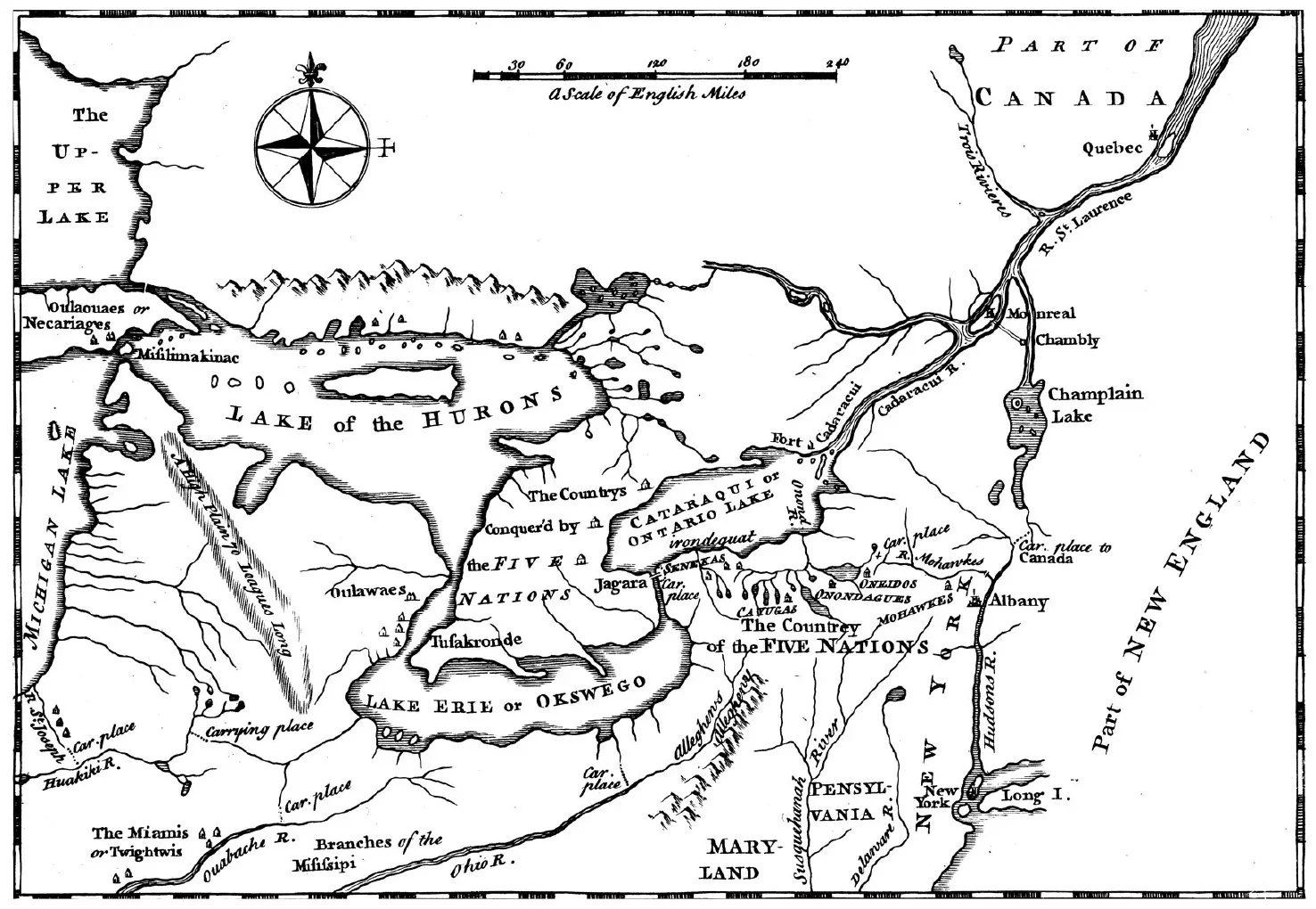

The Iroquois Wars

The mid-17th century was a period of near-constant danger for settlers in New France, especially in frontier communities like Trois-Rivières. Between 1650 and 1660, the colony endured repeated raids by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), who sought to control the fur trade and expand their territory. These attacks formed part of the larger conflict known as the Iroquois Wars (or Beaver Wars), during which colonists were frequently ambushed while farming, travelling, or tending livestock. Many were killed outright, while others were taken prisoner to be adopted into Iroquois communities or executed in ritual ceremonies. The losses suffered by Françoise Capel illustrate the personal toll of this violence. The fates of her two first husbands reflect the harsh realities of colonial life in a region caught between European settlement and Indigenous resistance during this turbulent decade.

Map of the initial nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, from History of the Five Indian Nations Depending on the Province of New-York, by Cadwallader Colden, 1755 (Encyclopædia Britannica)

Françoise’s Third Marriage

On February 1, 1660, notary Séverin Ameau drew up a marriage contract between Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capel. [Unfortunately, the deterioration of the document renders it illegible.] The marriage record no longer exists.

The marriage contract (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, July 2025)

Jacques and Françoise had four children:

Marie Madeleine (1660–1722)

Marie Françoise (ca. 1664–1740)

Marguerite (ca. 1666–bef. 1681)

Alexis (ca. 1668–1738)

Land Acquisitions

Over the following decade, Jacques and Françoise were involved in several real estate transactions.

October 9, 1661: Jacques received two small lots in the seigneurie of Cap-de-la-Madeleine from seigneur Pierre Boucher. The first measured twenty feet square and faced the street, intended for building a home. The second measured forty feet long by about twenty-two feet wide, for the purpose of building a barn. Jacques agreed to provide Boucher with two live chickens annually. He was unable to sign the document.

August 13, 1663: Jacques and Françoise planned to sell a plot of land located in the seigneurie of the Compagnie de Jésus (the Jesuits) in Trois-Rivières to Jean Tripier for 400 livres. The land, once belonging to Françoise’s second husband, measured two arpents of frontage on the Saint-Maurice River. However, the deed of sale was never completed by the notary, implying that the sale was not finalized.

March 24, 1666: Jacques received two plots of land located in the seigneurie of côte Saint-Éloy from the Compagnie de Jésus. Each parcel measured two arpents of frontage by forty arpents in depth. Jacques’s annual rente included wheat and two live capons, and his cens was set at four deniers annually. He agreed to have his grain milled at the seigneurial mill once it was built. The land concessions also included hunting and fishing rights.

The seigneurie of Saint-Eloy referred primarily to the area around Île-Saint-Eloy, near the confluence of the Batiscan River, the Champlain River, and the St. Lawrence River. It functioned as an extension or part of the broader Batiscan seigneurie, especially during the early colonial period of the 1660s. The location served as a strategic point for trade, missionary work, and eventually settlement.

November 14, 1667: Jacques and Françoise sold a house in the village of Trois-Rivières and a plot of land in Trois-Rivières to Charles de Montmesnier for 300 livres. This is the same plot they had intended to sell in 1663. Neither Jacques nor Françoise could sign the deed. Today, the southwest boundary of this lot would pass between Rue Brunelle and Rue Saint-Laurent, bordering Rue Dussault, and its depth would end beyond Rue Grandmont, in the heart of Cap-de-la-Madeleine. The house was located on Notre-Dame Street in Trois-Rivières.

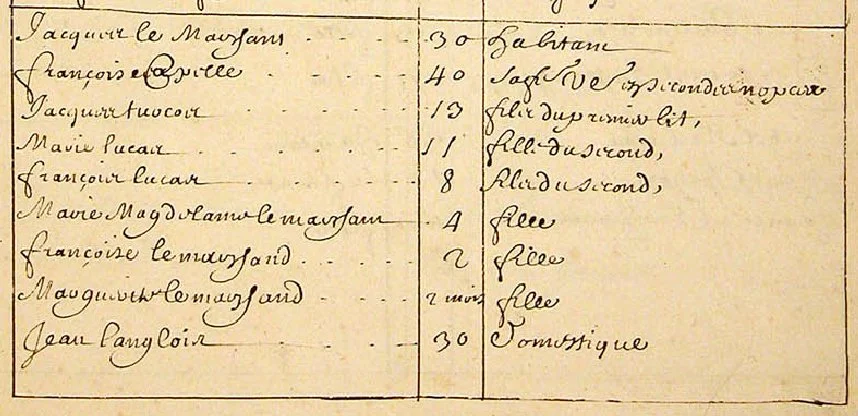

The Marchand Family in the Census

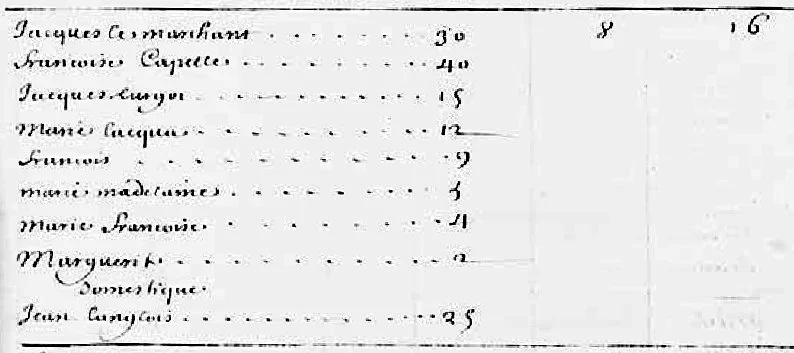

In 1666, Jacques and Françoise were recorded in the census of New France, living in Cap-de-la-Madeleine with their six children and a domestic servant named Jean Langlois. Jacques’s occupation was listed as habitant.

1666 census for the Marchand family (Library and Archives Canada)

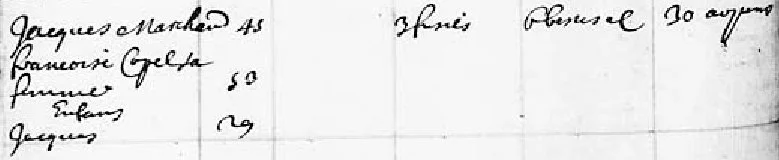

In 1667, another census was taken. Jacques and Françoise were living in “Petit Cap de la Magdeleine” with their children and servant Jean Langlois. The family owned sixteen arpents of "valuable" land (cleared and under cultivation) and eight animals.

1667 census for the Marchand family (Library and Archives Canada)

In the 1670s, Jacques and Françoise were involved in two additional land transactions.

March 14, 1671: Jacques and Françoise sold a plot of land at Cap-de-la-Madeleine to Michel Rochereau for 800 livres. The land measured two arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River.

May 28, 1674: Jacques and Françoise exchanged plots of land located in Saint-Éloy with Mathurin Guillet.

In 1674, Jacques was appointed churchwarden following the construction of the first parish church of Batiscan.

On December 22, 1679, Jean Gaudreau agreed to work for Jacques for one year in Batiscan. The contract, recorded by notary Antoine Adhémar, stated that Jean would perform “anything the Sieur Le Marchand commands him to” in exchange for 120 livres and a new pair of shoes. In addition, he would receive food, lodging, and laundry service.

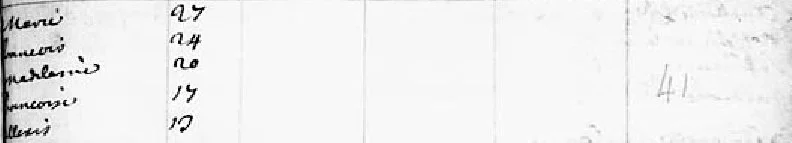

In November 1681, another census of New France was conducted. Jacques and Françoise were enumerated in Batiscan, living with their six children. They owned thirty arpents of cleared land, three guns, and six head of livestock.

1681 census for the Marchand family (Library and Archives Canada)

Life in Batiscan

According to a history of the parish of Champlain:

“Jacques Le Marchand settled at Saint-Eloi de Batiscan, near Champlain, where he obtained from the Reverend Jesuit Fathers a land concession in the upper part of the parish: six arpents in frontage by eighty in depth. The place where this new Abraham pitched his tent is full of freshness. The cheerful site, adorned with greenery, is crossed by flowing waters. To the northeast and northwest stretch vast wooded lands—a country of hunting and fishing. Beavers, caribou, bears, and wild animals abound there. Hares, pigeons, ducks, and game are plentiful. Trout, shad, whitefish, eel, and bass are a delight for the fisherman. The vegetation is rich. Cows graze in the beautiful meadows along the river. The deep green of oaks and pines mingles with the lighter greens of maples, beeches, elms, ashes, and cherry trees, shifting with the seasons in warm and changing tones that are a caress and a joy to the eye.

Wishing to combine the useful with the pleasant, Jacques Marchand surrounded his land with a wall and planted fruit trees—apple trees and plum trees. The lady of the house has her garden where vegetables compete with flowers for space. Roses, carnations, mignonettes, and marjoram open their blooms in turn, spreading their fragrances, mingling with the scents of the forest and fresh-cut hay. The hardworking housewife will make fine bundles from the hemp, which she will store away in the large armoire, already well stocked with linen cloth.”

The idyllic scenario described by Histoire de la paroisse de Champlain (artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT, July 2025)

Deaths of Jacques and Françoise

Jacques Marchand died at the age of about 57 on the morning of October 6, 1695, in Trois-Rivières. He was buried the following day inside the Immaculée-Conception parish church of Trois-Rivières. The burial record describes him as an habitant and bourgeois négociant (bourgeois merchant) of Batiscan.

1695 burial of Jacques Marchand (Généalogie Québec)

After Jacques’s death, Françoise asked notary Daniel Normandin to draft an agreement between her and her children (and their spouses) to settle her late husband’s succession.

Françoise Capel died at the age of about 73 on April 19, 1699, at the home of the “widow Turcot,” her daughter-in-law Marie Anne Desrosiers, who had just lost her husband (Françoise’s son) eleven days earlier. Another of Françoise’s sons, François Lucas, had died a month prior. The family was likely devastated by the smallpox epidemic that struck New France in 1699. Françoise was buried on April 20 in the Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation parish cemetery of Champlain.

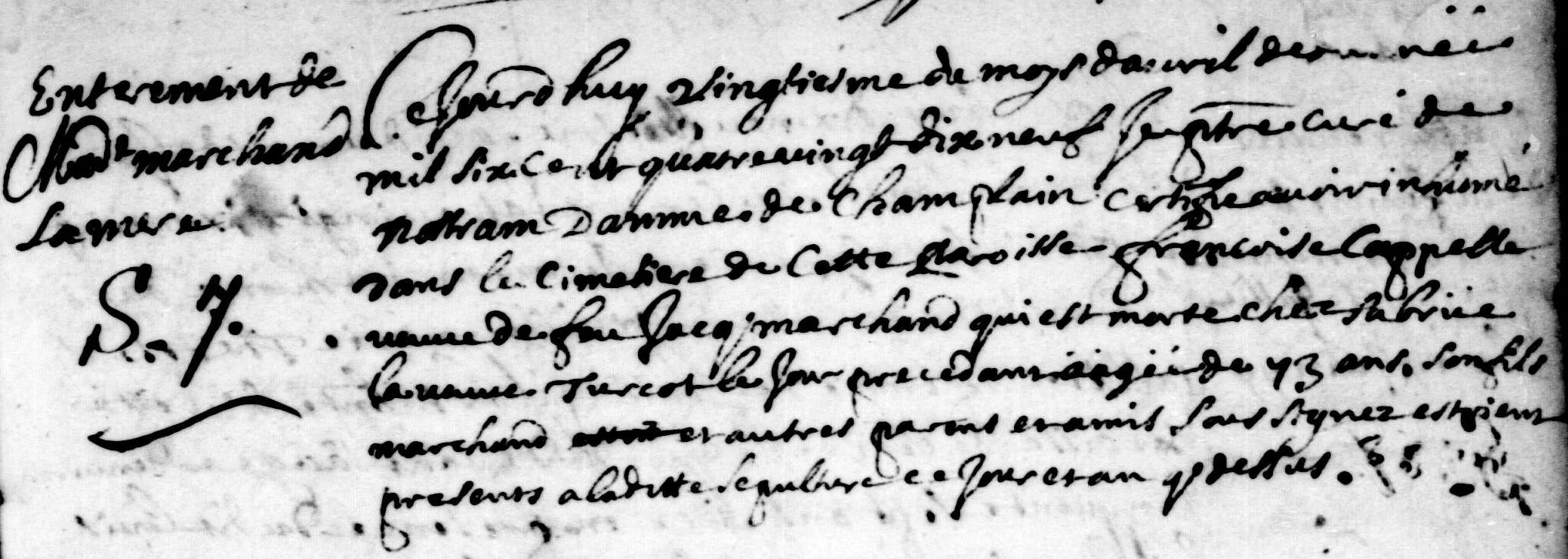

1699 burial of Françoise Capel (Généalogie Québec)

A year later, an inventory of Françoise’s communauté de biens (community of goods) was drafted by notary Normandin. The 12-page document listed all of her possessions, including clothing, linens, fabrics, tools, kitchen pots and utensils, furniture, farm animals, and brandy. The inventory also included her land:

At Batiscan, thirty feet of frontage facing the St. Lawrence River by forty feet deep, near the Champlain River, between the lands of François Fafard and Antoine Trottier dit Desruisseaux.

In the commune of Batiscan, thirty feet of frontage facing the St. Lawrence River by forty feet deep, bordering the lands of François Fafard on both the northeast and the southeast.

In the commune of Batiscan, about one-sixth of an arpent of frontage facing the St. Lawrence River by forty feet deep, bordering the land of Mr. Lavigne on the northeast and the land of Mr. Dutaux on the southwest.

Marchand Heritage

The Maison Marchand (Marchand House) is listed in the Répertoire du patrimoine du Québec (Quebec Heritage Directory). Located at 20 rue Principale, in Batiscan, the house was built in 1828. According to the heritage listing: “The first house was built closer to the river, like the first chapel. It was then rebuilt higher up using the same stones. The Marchand family is now in its 10th generation, since 1660.”

Maison Marchand (Jean-Pierre Chartier © MRC des Chenaux)

A Family Rooted in Courage and Community

The story of Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capel reflects both the hardships and the resilience of life in early New France. Françoise endured personal tragedy, losing two husbands to the violence of the Iroquois wars before finally finding stability with Jacques. Together, they overcame the dangers of frontier life and built a future in Batiscan. Jacques rose to become a churchwarden and merchant—an uncommon achievement for a former engagé. Their legacy lives on through the generations that followed, rooted in both survival and community leadership on the banks of the St. Lawrence River.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“Les engagés - XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles,” digital images, Archives départementales de Charente-Maritime (http://www.archinoe.net/v2/ark:/18812/d683e6b0c97331e9e53a588a7a8806b4 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), "Jacques Marchant, laboureur, engagé par François Peron, s'embarquera sur le navire Le Taureau," 11 Apr 1656, reference 3E 1128.

“51 – Les engagés levés par François Peron pour le Canada en 1656," Le Blogue de Guy Perron (https://lebloguedeguyperron.wordpress.com/2014/10/21/51-engages-leves-par-francois-peron-pour-le-canada-en-1656/ : accessed 14 Jul 2025).

"Actes de notaire, 1651-1702 // Ameau Séverin," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-73NG-1?cat=615650&i=119&lang=en : accessed 14 Jul 2025), marriage contract of Jacques Lucas dit Lespine and Françoise Capelle, 9 Nov 1653, images 120-122 of 2,436 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-73JW-J?cat=615650&i=345&lang=en : accessed 14 Jul 2025), marriage contract of Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capelle, 1 Feb 1660, image 346 of 2,436.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-73FV-F?cat=615650&i=507&lang=en : accessed 14 Jul 2025), land sale by Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capelle, 13 Aug 1663, image 508 of 2,436; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1659-1662 // Claude Herlin," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3V7-L2YH?cat=538141&i=2596&lang=en : accessed 14 Jul 2025), land concession to Jacques Marchand, 9 Oct 1661, images 2597-2598 of 2,621; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1664-1662 // Jacques de Latouche," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3773396?docref=MSpFHZsQLFlGkFTHI-_8zA%3D%3D : accessed 14 Jul 2025), land concession to Jacques Marchand, 24 Mar 1666, images 558-559 of 1,493; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3773396?docref=rzpVs6qE5bUHqKEsc5soRg%3D%3D : accessed 14 Jul 2025), house and land sale by Jacques Lemarchand and Françoise Capelle, 14 Nov 1667, images 1,101-1,102 of 1,493.

"Actes de notaire, 1666-1700 // Jean Cusson," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3V7-RXT1?cat=538059&i=279&lang=en : accessed 14 Jul 2025), land sale by Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capelles, 14 Mar 1671, images 280-281 of 1,574; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3V7-RD7G?cat=538059&i=584&lang=en : accessed 14 Jul 2025), land exchange by Jacques Marchand and Françoise Capelles, and Mathurin Guillet, 28 May 1674, images 585-586 of 1,574.

“Archives de notaires (Antoine Adhémar) // 1668-1714," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-9994-V?lang=en&i=1038 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), engagement of Jean Gottrau to Jacques Lemarchand, 22 Dec 1679, page 1,039 of 2,898; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1686-1729 // Daniel Normandin," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-W3VS-V?cat=538082&i=1368&lang=en : accessed 15 Jul 2025), agreement between Françoise Capelle and her children, 29 Nov 1695, pages 1,369-1,374 of 2,806; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-W3NK-N?cat=538082&i=2080&lang=en : accessed 15 Jul 2025), inventory of the goods of the succession of the late Françoise Capelle, 2 Apr 1700, pages 2,081-2,097 of 2,806

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 14 Jul 2025), household of Jacques Le Marchant, 1666, Trois-Rivières, page 152 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667", Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 17 Apr 2025), household of Jacques Le Marchant, 1667, Petit Cap de la Magdeleine, page 86 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), household of Jacques Marchand, 14 Nov 1681, Batiscan, pages 82-83 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/89538 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), burial of Jacques Marchant, 7 Oct 1695, Trois-Rivières (Immaculée-Conception).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/7210 : accessed 15 Jul 2025), burial of Francoise Cappelle, 20 Apr 1699, Champlain (Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation).

Relations des Jésuites, volume II (Québec, Augustin Coté Éditeur Imprimeur, 1858), 1651 chapter (pages 3-4), 1652 chapter (page 34-35).

Journal des Jésuites (Québec, Léger Brousseau Imprimeur-Éditeur, 1871), 266.

Jean-Philippe Marchand, "La seigneurie de Batiscan à l’époque de la Nouvelle-France (1636-1760)," thesis submitted to the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi as a partial requirement for the master's degree in regional studies and interventions, 12 Feb 2010 (https://constellation.uqac.ca/id/eprint/309/1/030131040.pdf : accessed 11 Jul 2025), 74.

"Iroquois Wars," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada (www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/iroquois-wars : accessed 14 Jul 2025), article published 7 Feb 2006, last edited 31 Jul 2019.

Peter Gagné, Before the King’s Daughters: Les Filles à Marier, 1634-1662 (Orange Park, Florida : Quintin Publications, 2002), 81.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Acte/94125 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), marriage contract of Jean Turcot and Francoise Capel, 25 Apr 1651, under private seign.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/679 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Jean TURCOT and Francoise CAPE, union 679.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/799 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques LUCAS and Francoise CAPE, union 799.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/1315 : accessed 14 Jul 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques MARCHAND and Francoise CAPE, union 1315.

Thomas J. Laforest, Our French-Canadian Ancestors vol. 4 (Palm Harbor, Florida, The LISI Press, 1986), 175.

Prosper Cloutier, Histoire de la paroisse de Champlain ([Trois-Rivières, Québec?] : [editor not identified], 1915), 367-368. Digitized by Canadiana (https://n2t.net/ark:/69429/m0fn10p11c7h : accessed 14 Jul 2025).

“Maison Marchand,” Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec (https://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/rpcq/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=195877&type=bien : accessed 15 Jul 2025), Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, Gouvernement du Québec.