Jacques Archambault & Françoise Toureau

From Aunis to Montréal’s first well-digger: the genealogy of Jacques Archambault & Françoise Toureau—sole ancestor of North American Archambaults.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jacques Archambault & Françoise Toureau

From Winemaker in Aunis to Well-Digger in Montréal

Jacques Archambault, son of Antoine Archambault and Renée Ouvrard, was born around 1604 in the hamlet of L’Ardillière, Aunis, France [today within Saint-Xandre, Charente-Maritime]. He was likely baptized in the nearby parish church of Saint-Pierre in Dompierre [present-day Dompierre-sur-Mer]. He had two known siblings: Denys and Anne. [In Canada, the Archambault surname appears in a variety of phonetic spellings in historical records.]

Location of Dompierre-sur-Mer in France (Mapcarta)

Église Saint-Pierre in Dompierre-sur-Mer (photos by Patrick Despoix, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Église Saint-Pierre in Dompierre-sur-Mer (photos by Patrick Despoix, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

The parish church of Saint-Pierre in Dompierre-sur-Mer dates to the 11th century. Damaged during the Wars of Religion, it was rebuilt after the royal capture of nearby La Rochelle in 1628. The present building preserves Romanesque elements and bears a commemorative plaque marking Jacques Archambault’s departure for Québec.

Françoise Toureau, daughter of François Toureau and Marthe Lenoir, was born around 1599 in Saint-Amant-de-Boixe, in Angoumois, France [now in the department of Charente], approximately 100 kilometres southeast of Dompierre-sur-Mer. [The Toureau surname appears in a variety of phonetic spellings in historical records.]

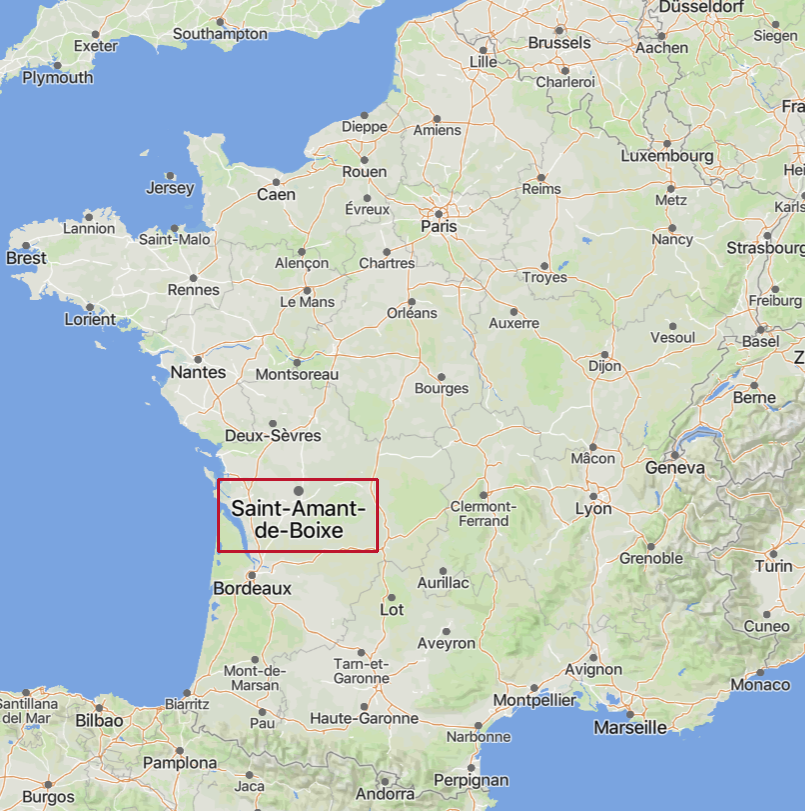

Location of Saint-Amant-de-Boixe in France (Mapcarta)

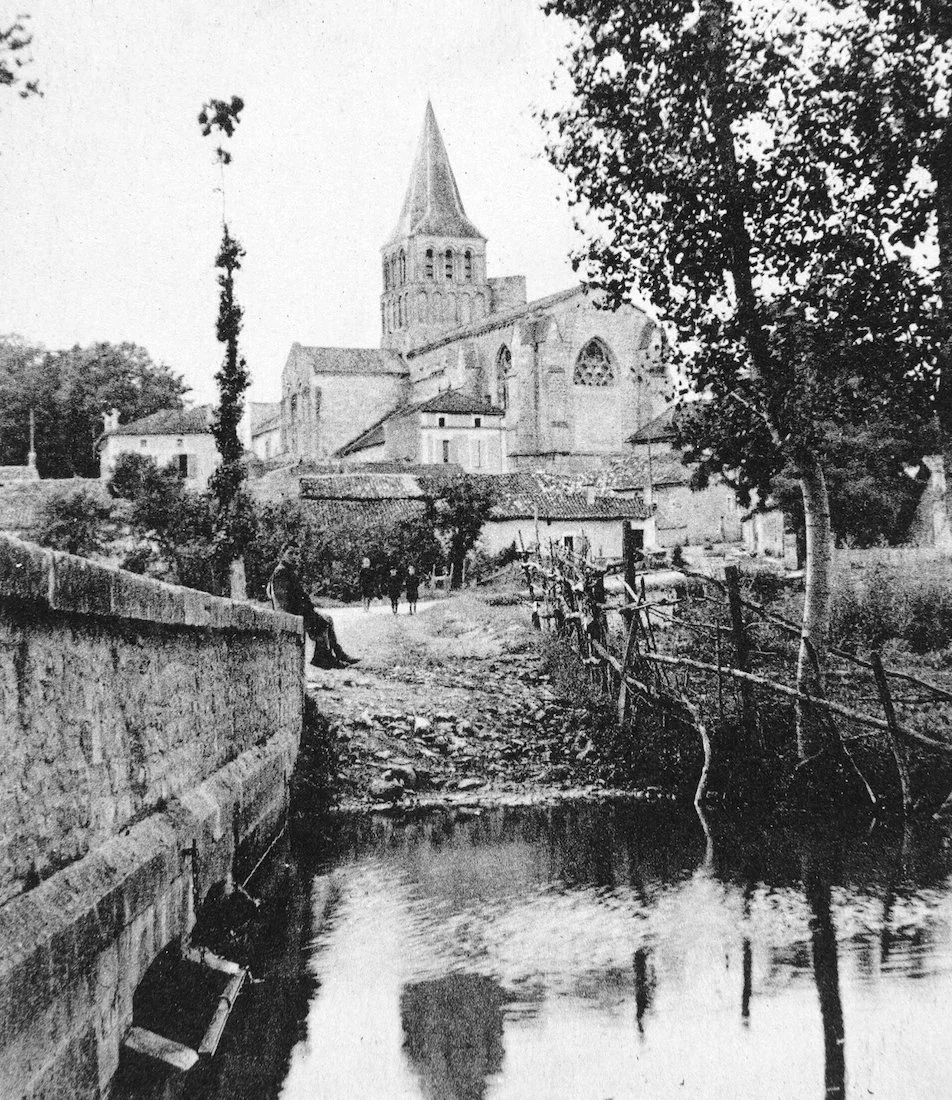

Saint-Amant-de-Boixe, circa 1905-1914 postcard (Geneanet)

Church of Saint-Amant-de-Boixe, circa 1905-1915 postcard (Geneanet)

Marriage and Children

Jacques and Françoise married around 1629; their marriage record has not been located. [A previously attributed marriage in Saint-Philbert-du-Pont-Charrault, cited by René Jetté, has since been corrected.]

They had seven children, likely all born in L’Ardillière:

Denis (1630–1651)

Anne (ca. 1631–1699), married Michel Chauvin (annulled) and Jean Gervaise

Jacquette (ca. 1634–1700), married Paul Chalifoux

Marie (1636–1719), married Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne

Louise (1640–bef. 1646)

Laurent (1642–1730), married Catherine Marchand

Marie (ca. 1644–1685), married Gilles Lauzon

Jacques’s professional life in France was tied to the land. He worked as a laboureur (ploughman) and possibly a vigneron (winemaker). This supposition comes from a contract dated August 15, 1637, in which he sold three barrels of white wine to Jérôme Bonnevye, a wine merchant from La Rochelle.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

Life in L’Ardillière: A Time of Turmoil

Life in L’Ardillière likely followed the rhythms of mixed farming on the limestone plain north of La Rochelle: grain for bread and feed, vines for everyday wine, and small stock (a pig, a cow, chickens). A laboureur like Jacques stood a notch above a day labourer but below larger tenant farmers; he likely owed seigneurial dues (cens, rentes), performed intermittent corvées (unpaid labour for the seigneur), and worked under local ban rights governing wine presses, harvest timing, and sales. The countryside around La Rochelle had long supported vines, alongside lowland saltworks.

The region surrounding Jacques's home was a hotspot of religious and military conflict. The devastating Siege of La Rochelle (1627–1628), a lengthy royal blockade of the Protestant stronghold, had a far-reaching impact. The siege brought famine and disease, and though Archambault’s village was not directly within the city walls, the effects of the conflict and the subsequent end of La Rochelle’s autonomy would have profoundly destabilized the local economy and social order.

This local turmoil was compounded by France's entry into the Thirty Years' War in 1635, which triggered sharp increases in the taille (land tax) and the conscription of troops. Even for families who remained neutral in the religious conflicts, the heavy financial burdens, the need to quarter soldiers (billeting), and the widespread market disruptions made rural life precarious and uncertain. The constant threat of periodic epidemics further heightened this sense of instability.

A New Start in New France

Against that backdrop, La Rochelle—France’s leading embarkation point for New France—was precisely where recruiters and shipowners reached rural Aunis families. The Company of One Hundred Associates, chartered in 1627 to populate the colony, promised land and support; yet before the 1660s most emigrants were young men, which makes a full household’s move in the 1640s rather unusual.

View of the port of La Rochelle, 1762 painting by Joseph Vernet (Wikimedia Commons)

Taken together, a capable laboureur-vigneron with six surviving children could plausibly judge that the risks of an Atlantic crossing were outweighed by the promise of land and security in New France, especially given the pressures on rural Aunis in those years.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

Around 1645, Jacques and Françoise decided to leave France. Researchers have speculated that the family may have arrived on the same ship as the director of the Compagnie des Habitants, Pierre Legardeur de Repentigny, on August 5, 1645, or more likely the following year on September 23, 1646. Their passage may also have been arranged or sponsored by Legardeur. The newly formed Compagnie des Habitants held a monopoly on the fur trade in New France from 1645 to 1663. Shortly after their arrival at Québec City, Jacques entered into service with Legardeur de Repentigny.

The Archambault family first settled in Québec. On October 15, 1647, notary Claude Lecoustre drew up a five-year farm lease between Jacques and Pierre Legardeur de Repentigny. Located at Repentigny Farm [present-day Upper Town in Québec], the lease included a two-room house, two oxen, two cows, a heifer, and some pigs. In return, Jacques was to develop and run the farm. The contract was complex: Jacques was already indebted to Legardeur, owing 898 livres, 10 sols, which he agreed to pay once the ships returned from France. The complex nature of this lease, including a provision for an additional 500-livres payment for "half of the land he would leave him in the first year," suggests that Jacques was immediately over-committed. The fact that he was unable to sign his name on the document and had to leave his mark further illustrates his vulnerability in these legal and financial dealings.

Jacques never saw Pierre Legardeur de Repentigny again. Legardeur died aboard Le Cardinal in May 1648. “He had barely left La Rochelle when an epidemic broke out on the ship that was carrying him. He became seriously ill and succumbed rapidly, ‘his body half covered with blackish purple spots as large as two-denier pieces.’”

On August 19, 1649, notary Laurent Bermen recorded an account of Jacques’s debts to Legardeur, which were being handled by Jean Juchereau. He still owed 384 livres, 7 sols. A year and a half later, on January 26, 1650, notary Guillaume Audouart dit Saint-Germain established an annual annuity between Jacques and Legardeur’s widow, Marie Favery. Jacques was recorded as a “former farmer on the land of Repentigny.” This document stated that he still owed the late Legardeur 800 livres. Jacques agreed to pay 44 livres, 8 sols, 10 deniers annually on each feast day of Saint-Michel.

Family Tragedy and Scandal in Montréal

Though Jacques and Françoise had settled in Québec, some of their children travelled on to Ville-Marie (Montréal), including Denis and Anne. By 1650, raids by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) had reduced the tiny settlement to a besieged outpost. Sulpician priest Dollier de Casson described the summer of 1651 as one of “incessant” alarms, with deaths nearly every month; settlers often clustered inside the fort or at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. On July 26, 1651, roughly 200 Iroquois assailed the Hôtel-Dieu. During the defence, Denis Archambault was “killed instantly by fragments from a cannon explosion.” He was buried the same day in the parish cemetery of Montréal.

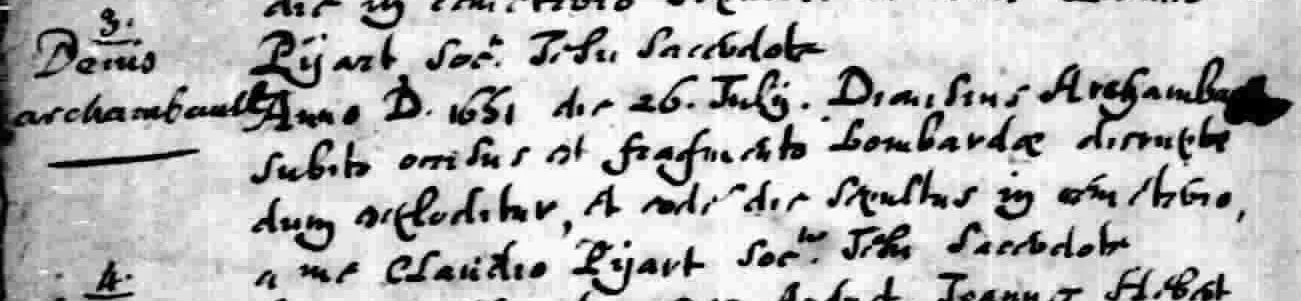

1651 burial of Denis Archambault, in Latin (Généalogie Québec)

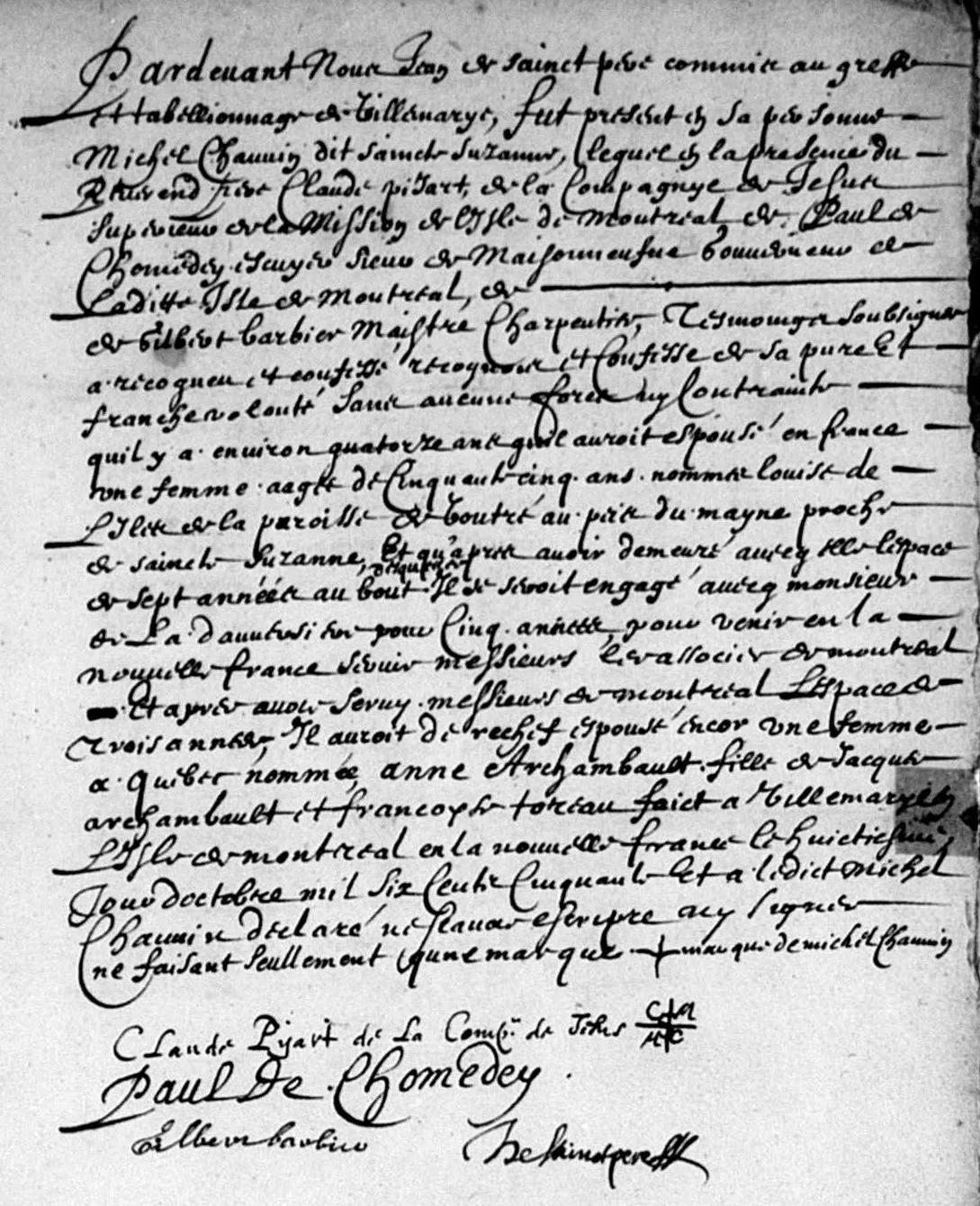

Michel Chauvin’s admission of bigamy in 1650 (FamilySearch)

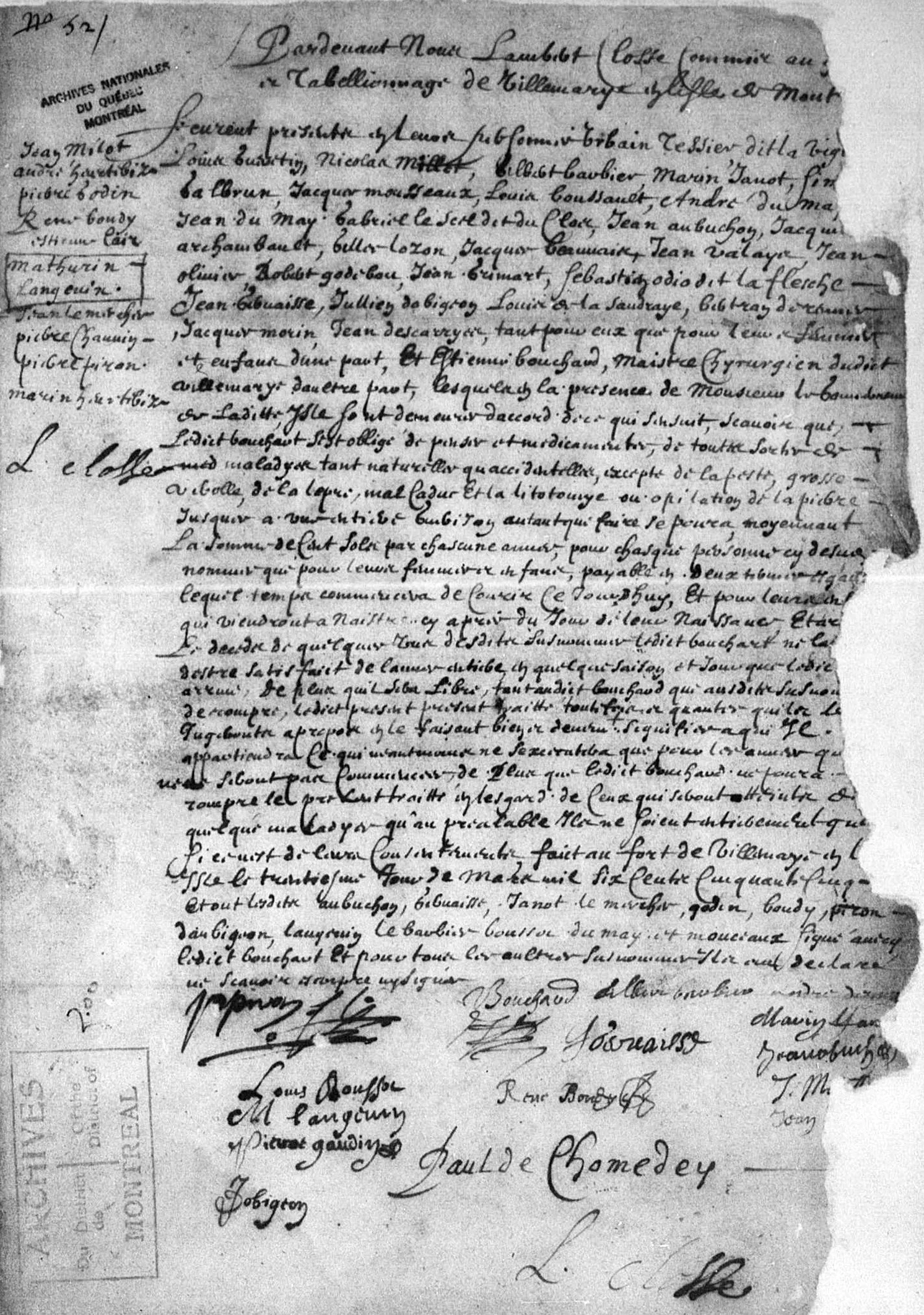

Anne had married Michel Chauvin in Québec on July 29, 1647, and bore him two children, only to discover that he was already married in France. On October 8, 1650, before Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, notary Saint-Père, and several witnesses in Montréal, Chauvin admitted that “about 14 years ago, he married in France a 55-year-old woman named Louise de Lille of the parish of Voutré in the land [province] of Maine near Sainte-Suzanne, and that after living with her for a period of seven years, he agreed to a work contract with Mr. de La Dauversière for five years to come to New France […] and after a period of three years he had married again a woman in Québec named Anne Archambault, daughter of Jacques Archambault and Françoise Toreau […].”

Chauvin returned to France shortly after his declaration of bigamy, and his marriage to Anne was annulled. In 1654, she married master baker Jean Gervaise. Together, they had nine children.

Competing Land Concessions

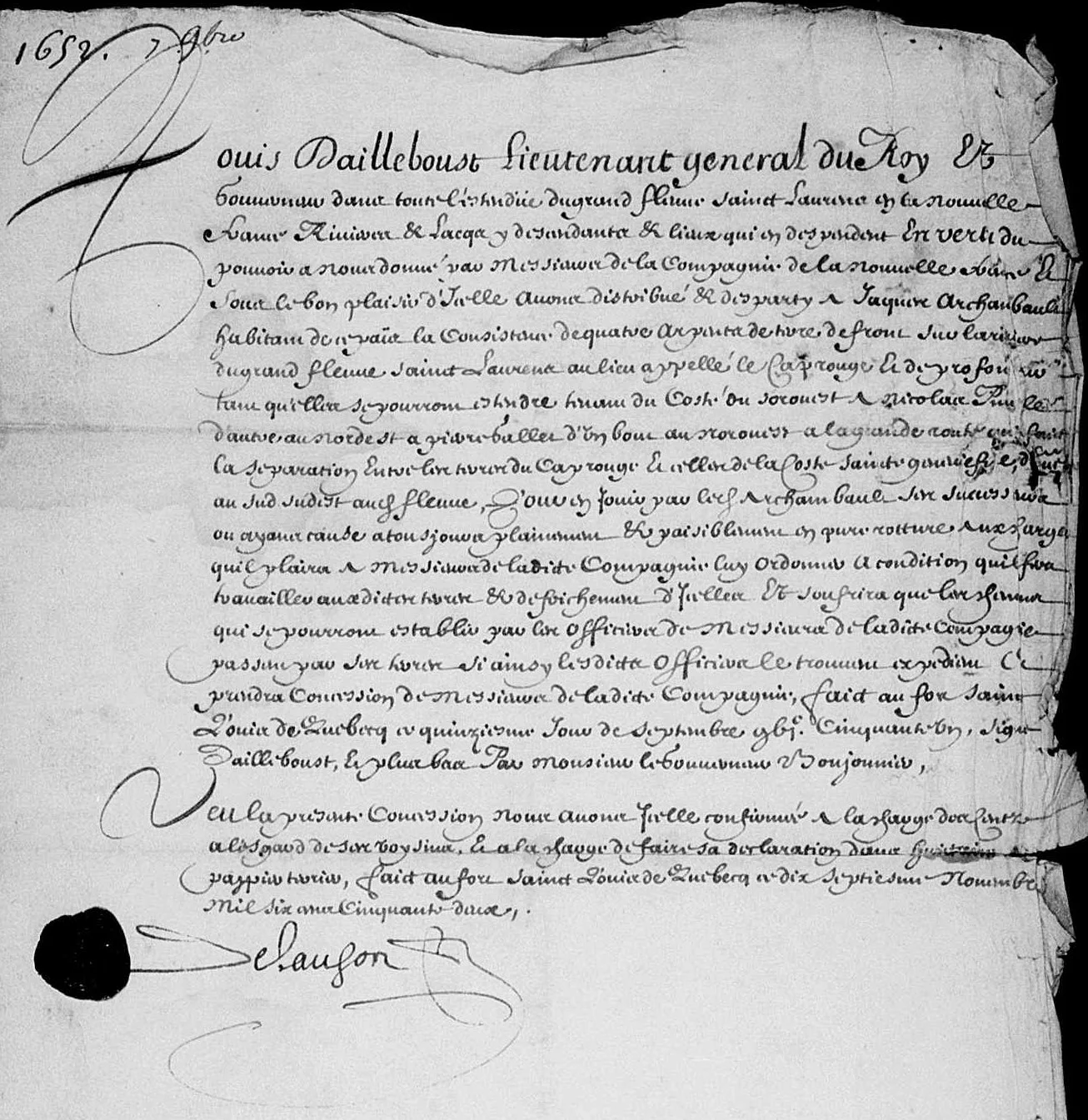

While the family navigated loss and upheaval, Jacques secured land in both Québec and on the island of Montréal. On September 15, 1651, he received a concession at “cap Rouge” from the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France (Company of One Hundred Associates): four arpents of frontage on the St. Lawrence River, bordering the concessions of Nicolas Pinel and Pierre Gallet, and the main road separating Cap Rouge from côte Sainte-Geneviève. Jacques promised to work and clear the land. The grant was ratified by Governor de Lauson and penned by notary Audouart at Fort Saint-Louis in Québec on November 17, 1652.

1652 land concession to Jacques Archambault (FamilySearch)

Just three days after the 1651 Québec concession, on September 18, 1651, the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, seigneur of the island, granted Jacques a parcel “on the edge of the property adjoining the land reserved for the construction of a town,” measuring two arpents by 15 deep, between the lands of his son-in-law Urbain Tessier and Lambert Closse. Today, the concession would lie in Old Montréal, running south–north from rue Saint-Jacques to rue Ontario. Its eastern edge followed rue Saint-Laurent; on the west, it stopped just east of Place d’Armes and, farther north, just east of rue Saint-Urbain. Jacques also received one arpent within the town limits.

The following year, on November 17, 1652, Jacques received an additional lot within the settlement of Montréal, adjacent to his 1651 concession. This parcel extended from rue Saint-Jacques towards rue Notre-Dame, without quite reaching it, and measured two arpents wide by one arpent long.

By February 3, 1654, Jacques was in Montréal attending Anne’s marriage to Jean Gervaise. Later that month, on February 15, he accepted an offer from Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve to settle in Montréal in exchange for a 300-livre gratuity. Jacques and Françoise likely moved to be closer to most of their children (only Jacquette remained in Québec).

On September 23, 1654, notary Louis Rouer de Villeray drew up an unusual deed of sale: Étienne Dumais sold Jacques “a house built by him on the concession of the said Archambault, of which house the said Dumais agrees to return the floor to the state it was in previously, so that the said house can be sold and enjoyed by the said Archambault,” for 71 livres. Jacques paid a deposit of 21 livres and promised to pay the remainder the next day in beaver pelts. The circumstances—how Dumais came to build a house on another man’s concession—are unclear.

Ville-Marie or Montréal?

In seventeenth-century records, Ville-Marie and Montréal refer to the same place—the mission-fort founded by Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance on the site of today’s Old Montréal. Maisonneuve styled the settlement “Villemarie on the island of Montréal in New France.” The name Ville-Marie appeared in print in 1643 in Les véritables motifs de messieurs et dames de la Société de Nostre Dame de Montreal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle France and that year’s Relations des Jésuites, and both names were used interchangeably until 1669.

“Montréal,” originally the name of the mountain and then the island (from Cartier’s Mont Royal), came to be used for the town itself in civil and ecclesiastical documents, especially after the Sulpicians became seigneurs in 1663 and the parish was styled Notre-Dame de Montréal. By the late seventeenth century—and increasingly into the early eighteenth—official acts favoured “Montréal,” though both terms appear, with “Ville-Marie” typically used when writers emphasized the original mission and fort.

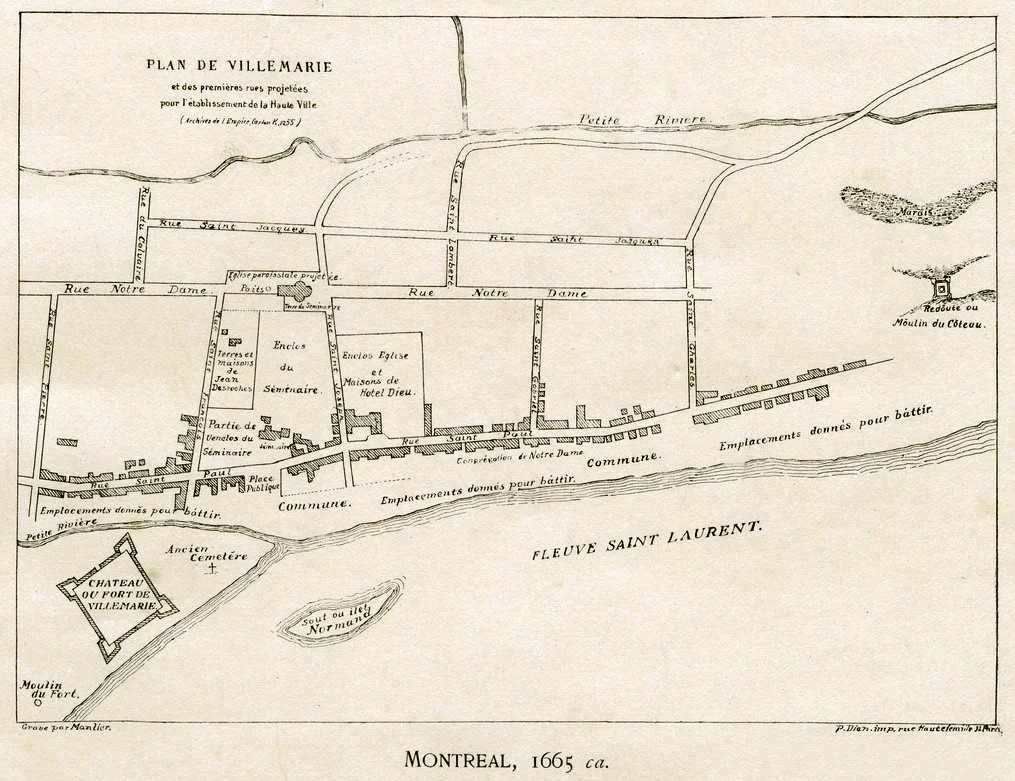

Map of Montreal from 1650 to 1672, drawn by P.-L. Morin in 1884 and published by H. Beaugrand (Archives de Montréal)

A Pioneering Community Health-Care Agreement

1655 agreement between the men of Ville-Marie and master surgeon Étienne Bouchard (FamilySearch)

On March 30, 1655, a kind of community medical-care agreement was concluded between three dozen men residing in Ville-Marie—including Jacques and three of his sons-in-law—and master surgeon Étienne Bouchard. Speaking on behalf of their wives and children, the men likely represented most of the settlement’s roughly 150 inhabitants. Bouchard “undertook to treat and prescribe medication for all kinds of illnesses, both natural and accidental, except for the plague, smallpox, leprosy, epilepsy, and lithotomy or stone removal, until complete recovery as far as possible, for the sum of one hundred sols per year for each of the above-named persons, as well as for their wives and children [...].” The agreement, penned by notary Raphaël-Lambert Closse at the Fort of Ville-Marie, is considered the first of its kind on the continent.

On February 13, 1657, Jacques made his move to Montréal permanent. On that date, he granted proxy to the Jesuit priest Jean de Quen of Québec “to sell, rent, lease or let the house and land belonging to [Archambault] in the Cap Rouge district near Quebecq.”

Around this time, Jacques, his son-in-law Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne, and François Bailly dit Lafleur were placed in charge of the redoute de l’Enfant-Jésus, a small wooden redoubt above the coteau Saint-Louis at the end of Tessier’s land. Built to shelter and defend field workers north of the original fort, the redoubt reflected the constant danger of surprise Haudenosaunee raids in the early 1650s.

The Occupation of Well-Digger

Now firmly established in Montréal, Jacques began the work for which he is best remembered: well-digging. For a frontier settlement under threat, a reliable well was safer and easier than hauling water from the St. Lawrence River.

October 11, 1658: Jacques was hired by Governor Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve to dig a well in the fort of Ville-Marie, in the middle of the Place d’Armes courtyard. The well was to measure five feet in diameter and contain “at least two feet of stable water” at the bottom. His pay was 300 livres and ten jars of eau-de-vie (brandy). This was the first well dug in Montréal.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (August 2025)

June 8, 1659: The priests of the Hôtel-Dieu of Montréal hired Jacques to dig a well in the hospital garden with the same specifications and wages—300 livres and ten jars of brandy. The priests supplied most construction materials.

May 17, 1660: Merchants Jacques Le Ber, Charles Le Moyne, and Jacques Testard hired Jacques to dig a well on the communal land of Ville-Marie, to the same dimensions and terms. Testard took sixteen years to pay his one-third share!

November 6, 1664: Claude Robutel dit Saint-André hired Jacques to dig a courtyard well for 150 livres.

July 11, 1668: Merchant Étienne Bauchaud hired Jacques to dig a well on his land for 250 livres.

On August 24, 1660, Paul de Chomedey, Jacques, and 105 other men of Montréal received the sacrament of confirmation from François de Montmorency-Laval, “Monsignor the Illustrious and Most Reverend Bishop of Petrée, Vicar Apostolic in the whole of New France.”

Defending Montréal

A resurgence of Haudenosaunee attacks in the 1660s forced the small settlement to organize its own defence. In 1663—two years before the arrival of royal troops (the Carignan-Salières Regiment in 1665)—de Maisonneuve created a civic militia to protect outlying fields and guard posts.

The Sainte-Famille Militia

In 1663, facing repeated and deadly attacks by the Iroquois, Montréal's residents were left to defend themselves in the absence of formal military support. In response, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, established the first Canadian militia. He called upon the men of Montréal to organize themselves into groups of seven, each led by a corporal of their choosing. This local force was placed under the patronage of the Holy Family—Jesus, Mary, and Joseph—and named the Sainte-Famille militia. The final roll listed 139 men, likely representing all able-bodied males in the small settlement, which had a population of around 500 at the time.

Squadron Eight, led by Claude Robutel, included Jacques’s sons-in-law Jean Gervaise and Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne. Squadron Ten, led by Jacques Testard dit Laforest, included his son Laurent. Squadron Fourteen, led by De Sailly, included his son-in-law Gilles Lauzon.

On November 2, 1663, Jacques, Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne, and François Bailly dit Lafleur transferred their rights and responsibilities at the redoute de l’Enfant-Jésus to Jean Auger de Baron, who promised to maintain round-the-clock guard for Montréal’s residents. Tessier sold Auger the square arpent on which the redoubt stood for 100 livres.

On December 15, 1663, Jacques leased Pierre Dardenne his farm for “three consecutive harvest years,” beginning April 1.

Death of Françoise Toureau

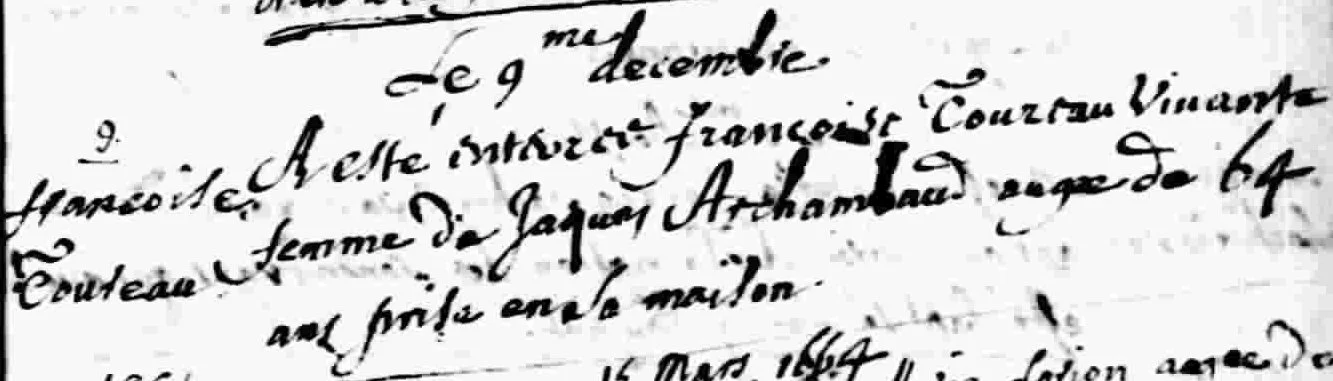

Françoise Toureau died at about 64 years of age. She was buried on December 9, 1663, in the Notre-Dame parish cemetery in Montréal. The translated record reads:

“On December 9 was buried Françoise Toureau, the wife of Jacques Archambault, aged 64, who died at her home.”

1663 burial of Françoise Toureau (Généalogie Québec)

A Second Marriage

On June 6, 1666, notary Séverin Ameau drafted a marriage contract in Trois-Rivières between Jacques and Marie Denault de Lamartinière. He was about 62; she was approximately 54, a resident of Trois-Rivières and three times widowed. Their marriage record has not been located, but couples generally married within three weeks of their marriage contract. Given their ages, no children were born of this union.

Two years later, on April 26, 1668, Françoise’s succession was finalized. Her community of goods with Jacques was settled under the Coutume de Paris after a valuation of their property, including five plots of land. Jacques received half of the 30-arpent holding (his portion bordered that of Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne); the surviving children received the other half—three square arpents each. The valuation and survey were conducted while Jean Gervaise was absent. Two years later, he filed his formal opposition to the land survey before notary Bénigne Basset; the outcome is unknown.

Census enumerators missed Jacques Archambault in the 1666 census of New France. He and his wife Marie appeared in the 1667 census as residents of the island of Montréal. They held 30 arpents of “valuable” land (cleared and under cultivation) and owned no farm animals.

1667 census of New France for Jacques and Marie (Library and Archives Canada)

The Changing Landscape of Montréal

In the early 1670s, Montréal was undergoing a crucial transformation. After decades of organic and often haphazard development, the settlement’s religious seigneurs—the Sulpicians—decided it was time to impose a formal street plan. Under the leadership of François Dollier de Casson, with the assistance of notary and surveyor Bénigne Basset, the first official alignments of streets were drawn and recorded. The layout would shape the future of the colony, redefining property boundaries, and opening the way for structured development. It also required the cooperation—and sometimes the reluctant acquiescence—of Montréal’s landowners, whose concessions would now be intersected by public thoroughfares.

"Montreal, 1665. Plan of Ville-Marie and the first streets planned for the establishment of the Upper Town" (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Jacques was among those directly affected by this new order. Two of the newly formalized streets, Saint-Jacques and Saint-Lambert, crossed or bordered his property. He attended the March 12, 1673, meeting where residents were asked to relinquish any claim to the lands now designated as public roadways. The records show he did not object, unlike his son-in-law Gilles Lauzon, who initially resisted. His willingness to yield land illustrates both the power of the seigneurial system and the role of long-standing colonists in shaping early Montréal.

Perhaps as a result, on December 3, 1675, Jacques sold a portion of his in-town land to the Sulpicians for 100 livres. The parcel measured five perches three feet long by twelve feet wide, bordering property owned by the priests, by Truteau, by Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne, and by rue Saint-Jacques.

Jacques’s Final Years

Advancing in age—“a septuagenarian and very powerless and unable to work to earn a living” —Jacques entered a family support arrangement. On June 25, 1678, his son Laurent and sons-in-law Jean Gervaise, Urbain Tessier, and Gilles Lauzon agreed to provide him a lifelong pension, covering food and well-being up to a maximum of 25 livres each per year.

On November 13, 1679, Jacques sold part of his land to his son-in-law Jean Gervaise for 624 livres and five sols. The parcel measured fourteen arpents and formed part of his original thirty-arpent concession. It bordered the lands of Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne and of Lambert Closse’s widow, Marie Élisabeth Moyen.

Jacques and Marie appeared in the 1681 census of New France as residents of the island of Montréal. According to the return, they had no “valuable” land, no farm animals, and no guns.

1681 census of New France for Jacques and Marie (Library and Archives Canada)

On April 6, 1684, “considering the long-standing friendship he has always shown and continues to show towards Jacques Archambault, his father-in-law,” Jean Gervaise agreed to house, feed, and care for him until his death. In exchange, Jean was released from future contributions to Jacques’s pension.

Death of Jacques Archambault

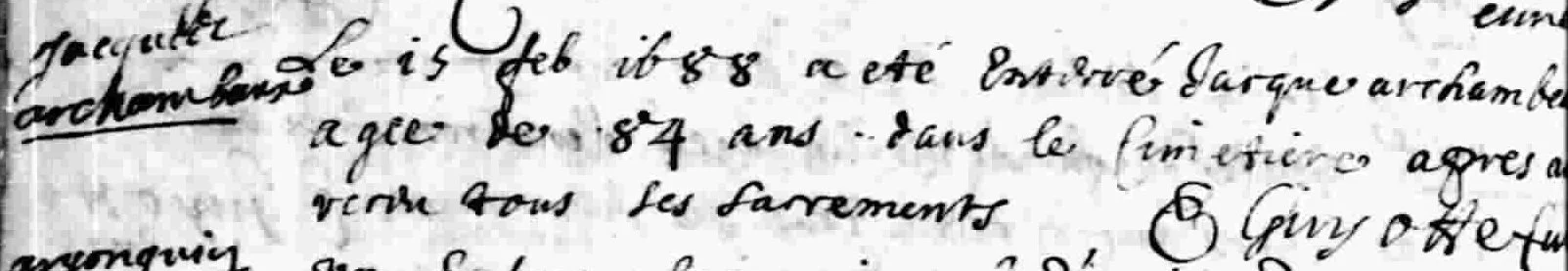

Jacques Archambault was buried on February 15, 1688, in the parish cemetery of Notre-Dame in Montréal. The translated burial record reads:

“On 15 February 1688, Jacques Archamb[eau?], aged 84, was buried in the cemetery after receiving all the sacraments.”

1688 burial of Jacques Archambault (Généalogie Québec)

The Archambault Family Legacy

Rue Jacques-Archambault in Montréal (Google)

From L’Ardillière to Montréal, Jacques Archambault’s life—from laboureur in Aunis to well-digger and early landholder in Montréal—embodies the labour, risk, and community-building that shaped the colony. With Françoise Toureau, and through alliances with other pioneer families, he anchored a lineage that spread with the growth of New France and, later, Canada and the United States. Today, Jacques is recognized as the sole ancestor of all North American Archambaults, with over 20,000 descendants across the continent.

Les Archambault d’Amérique, the Archambault family association, was founded in January 1983 “to establish and maintain warm relations between the descendants of their common ancestor, Jacques Archambault.”

Several sites now commemorate Jacques and his place in Montréal’s early history. On February 15, 1988, Les Archambault d’Amérique inaugurated Rue Jacques-Archambault in the Pointe-aux-Trembles neighbourhood to mark the tricentennial of their ancestor’s death.

In 1992, the association installed a plaque on the Mussen building (now a McDonald’s) at the corner of Notre-Dame and Saint-Laurent streets in Montréal. The translated text reads: “On September 18, 1651, Monsieur de Maisonneuve, founder of Montreal, granted this site to Jacques Archambault, one of the pioneers of this city and our common ancestor.”

Commemorative plaque (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

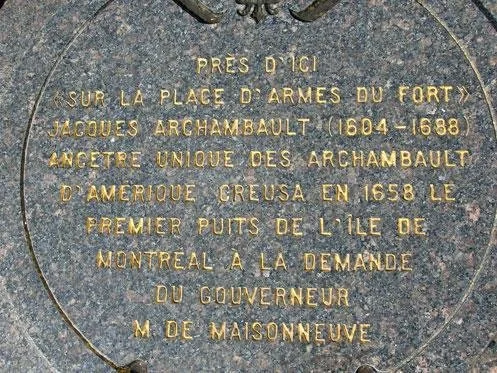

In Old Montréal, near the south-west corner of the Pointe-à-Callière Museum, a replica of the city’s first well commemorates Jacques Archambault’s 1658 work in the fort’s Place d’Armes courtyard. The translated inscription reads: “Nearby, on the Place d'Armes du Fort, Jacques Archambault (1604-1688), sole ancestor of the North American Archambault family, dug the first well on the island of Montreal in 1658 at the request of Governor Mr. de Maisonneuve.”

Replica of Montréal’s First Well (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

Replica of Montréal’s First Well (Pascale Llobat 2008, © Ministère de la Culture et des Communications)

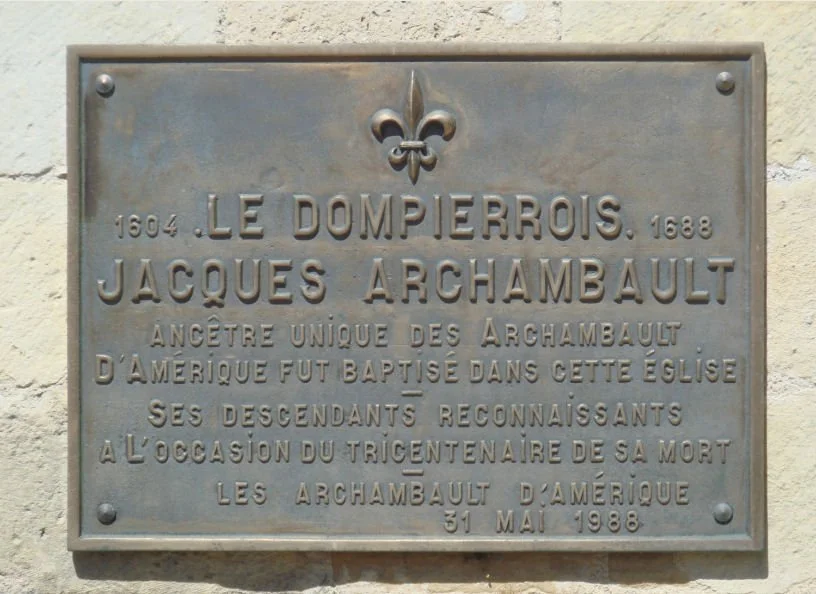

In 1988, Les Archambault d’Amérique also placed a plaque on the church of Dompierre-sur-Mer, where Jacques was likely baptized.

Commemorative plaque in Dompierre-sur-Mer (photo by Uploadlr, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Cap-Rouge, in 2001, the association installed a plaque on the site of the land occupied by Jacques, celebrating the 350th anniversary of this concession.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/48694 : accessed 19 Aug 2025), burial of Denis Archambault, 26 Jul 1651, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66365 : accessed 19 Aug 2025), marriage of Michel Chauvain and Anne Archambault, 29 Jul 1647, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/48803 : accessed 20 Aug 2025), burial of Francoise Toureau, 9 Dec 1663, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/49276 : accessed 24 Aug 2025), burial of Jacques Archambeau, 15 Feb 1688, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

"Registre des confirmations 1649-1662," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/membership/fr/fonds-drouin/REGISTRES : accessed 22 Aug 2025), confirmation of Jacques Archambault, 24 Aug 1660, Montreal; citing original data: Registre des confirmations, Diocèse de Québec, Registres du Fonds Drouin.

"Archives de notaire : Claude Lecoustre (1647-1648)," Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/5124961?docref=CJHZBu63xKtdhPdMz1J2Sg : accessed 19 Aug 2025), farm lease between Jacques and Pierre Legardeur de Repentigny, 15 Oct 1647, images 36-37 of 98.

"Actes de notaire, 1647-1649 // Laurent Bermen," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-Q84M?cat=1175227&i=560&lang=en : accessed 19 Aug 2025), statement of account between Jacques Archambault and Jean Juchereau de Morre, 19 Aug 1649; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1634, 1649-1663 // Guillaume Audouart," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-32TJ?cat=1171569&i=126&lang=en : accessed 19 Aug 2025), establishment of an annual annuity between Jacques Archambault and Marie Favery, 26 Jan 1650; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-3JNN?cat=1171569&i=654&lang=en : accessed 19 Aug 2025), land concession to Jacques Archambault, 17 Nov 1652, image 655 of 2,642.

"Actes de notaire, 1648-1657 // Jean de Saint-Père," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-L3V7-V9Z4-Y?cat=674697&i=426&lang=en : accessed 19 Aug 2025), declaration of Michel Chauvin dit Sainte Suzanne, 8 Oct 1650; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3V7-V962-4?cat=674697&i=488&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), proxy from Jacques Archambault to Jean de Quen of Quebec, 13 Feb 1657, image 489 of 2,864.

"Actes de notaire, 1653-1657 // Louis Rouer," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-Q8HK?cat=1176006&i=603&lang=en : accessed 19 Aug 2025), house sale by Etienne Dumetz to Jacques Archambault, 23 Sep 1654, image 604 of 2,056; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1651-1657 // Raphaël-Lambert Closse," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-5QWZ-X?cat=481205&i=2957&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), agreement between master surgeon Etienne Bouchard and the residents of Montréal, 30 Mar 1655, image 2,598 of 2,984; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-RQ56-R?cat=426906&i=1042&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), contract for the digging of a well between Jacques Archambault and Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, 11 Oct 1658, image 1,043 of 3,055; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-RQ5G-H?cat=426906&i=1145&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), contract for the digging of a well between Jacques Archambault and the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, 8 Jun 1659, images 1,146-1,147 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-RQB8-H?cat=426906&i=1380&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), contract for the digging of a well between Jacques Archambault and Jacques Leber, Charles Lemoyne and Jacques Testard, 17 May 1660, images 1,381-1,382 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-2WXY-P?cat=426906&i=146&lang=en : accessed 25 Aug 2025), receipt from Jacques Archambaut to Jacques Testard de Laforests, 26 Nov 1676, image 147 of 3,049.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-R7S4-P?cat=426906&i=2174&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), contract for the digging of a well between Jacques Archambault and Claude Robutel, 6 Nov 1664, image 2,175 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-RQGY-8?cat=426906&i=2749&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), contract for the digging of a well between Jacques Archambault and Etienne Bauchaud, 11 Jul 1668, images 2,751-2,752 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-RQ5M-R?cat=426906&i=2077&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), transfer of rights to a redoubt named La Redoute de L'Enfant Jesus by Jacques Archambaut, Urbain Tessier dit Lavigne, and François Bailly dit Lafleur to Jean Auger dit Baron, 2 Nov 1663, images 2,077-2,078 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-R7S4-1?cat=426906&i=2119&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), farm lease by between Jacques Archambault to Pierre Dardenne, 15 Dec 1663, images 2,120-2,121 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-RQGL-W?cat=426906&i=2700&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), succession of Françoise Toureau, 26 Apr 1668, images 2,701-2,713 of 3,055.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NX6L?cat=426906&i=402&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), opposition of Jean Gervaise to the survey of Jacques Archambault’s land, 31 Jul 1670, images 403-404 of 3,072.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NXWS?cat=426906&i=1550&lang=en : accessed 22 Aug 2025), agreement between the Séminaire de St-Sulpice de Montréal and the landowners of Montréal, 12 Mar 1673, images 1,551-1,552 of 3072.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NNC4?cat=426906&i=2766&lang=en : accessed 22 Aug 2025), land sale by Jacques Archambault to Gilles Perrot of the Séminaire de St-Sulpice de Paris, 3 Dec 1675, images 2,767-2,769 of 3072.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-2WZH-2?cat=426906&i=566&lang=en : accessed 22 Aug 2025), donation of a life-long pension by Jean Gervais, Urbain Tessier, Gilles Lauzon, and Laurent Archambault to Jacques Archambault, 25 Jun 1678, images 567-568 of 3,049.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-2WZX-9?cat=426906&i=771&lang=en : accessed 24 Aug 2025), agreement between Jacques Archambault and Jean Gervaise, 6 Apr 1684, images 772-773 of 3,049.

"Actes de notaire, 1651-1702 // Ameau Séverin," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-73NM-C?cat=615650&i=750&lang=en : accessed 20 Aug 2025), marriage contract of Jacques Archambault and Marie Denot, 6 Jun 1666, images 751-752 of 2,436; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1677-1696 // Claude Maugue," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-GSF8-5?cat=427707&i=195&lang=en : accessed 22 Aug 2025), land sale by Jacques Archambault to Jean Gervais, 13 Nov 1679, images 196-197 of 2,531; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 20 Aug 2025), "Dépôt d'une concession de terre située sur le bord des fonds joignant les terres réservées pour la construction d'une ville; par la Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal, seigneur de l'île de Montréal, à Jacques Archambaut," private contract, 12 Oct 1663 (original drafted 18 Sep 1651).

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 20 Aug 2025), household of Jacques Archambaut, 1667, Montréal, page 160 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 22 Aug 2025), household of Jacques Archambaud, 14 Nov 1681, Montreal, page 165 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/1463 : accessed 19 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques ARCHAMBAULT, person 1463.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/1464 : accessed 19 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Francoise TOUREAU, person 1464.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/138 : accessed 19 Aug 2025), dictionary entry for Jacques ARCHAMBAULT and Francoise TOUREAU, union 138.

"Notre ancêtre," Les Archambault d’Amérique (https://lesarchambaultdamerique.com/news/notre-ancetre/ : accessed 19 Aug 2025).

"Jacques Archambault premier puisatier de Ville-Marie," Les Archambault d’Amérique (https://lesarchambaultdamerique.com/news/jacques-archambault-premier-puisatier-de-ville-marie/ : accessed 19 Aug 2025).

René L’Heureux, “Simon L’Hérault : 1er ancêtre canadien des familles L’Hérault et L’Heureux,” Mémoires de la Société généalogique canadienne-française, volume XX, number 2, April-May-June 1969.

Boyko, John, "Company of One Hundred Associates," in The Canadian Encyclopedia, 16 Dec 2013, Historica Canada (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/compagnie-des-cent-associes : accessed 19 Aug 2025).

Jean Hamelin, “LEGARDEUR DE REPENTIGNY, PIERRE (d. 1648),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/legardeur_de_repentigny_pierre_1648_1E.html : accessed 19 Aug 2025), University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–.

Dollier de Casson, Histoire du Montréal, 1640-1672, digitized by Wikisource (https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Dollier_de_Casson_-_Histoire_du_Montr%C3%A9al,_1640-1672,_1871.djvu/2 : accessed 19 Aug 2025), page 42.

Yvon Sicotte, Base de données – Les Premiers Montréalais (https://lespremiersmontrealais.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/7-3-1-les-immigrants.pdf : accessed 24 Aug 2025), entry for Jacques Archambault, page 8.

Marcel Fournier, Les Premiers Montréalistes : 1642-1643 (Montréal, Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo Inc., 2013), 31.

"Archambault, Jacques," Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec (https://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=14712&type=pge : accessed 20 Aug 2025).

E.-Z. Massicotte, "La milice de 1663," Le Bulletin des recherches historiques, volume XXXII, number 7, July 1926.

Michel Langlois, Montréal 1653 : La Grande Recrue (Sillery, Les éditions du Septentrion, 2003), 68.

"La verbalisation des premières rue de Montréal," Le Bulletin des recherches historiques, vol. XXXVIII, number 10, 610-619, Lévis, Oct 1932, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2657386 : accessed 22 Aug 2025).

Brigitte Maillard, “Chapitre 4. Le régime seigneurial : droits fonciers et pouvoirs financiers,” Les campagnes de Touraine au XVIIIe siècle, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 1998, digitized by OpenEdition Books (https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.17124 : accessed 19 Aug 2025).

Mathias Tranchant, “La place du sel dans l’économie rochelaise de la fin du Moyen Âge,” Le sel de la Baie, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2006, digitized by OpenEdition Books (https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.7618 : accessed 19 Aug 2025).