Guillaume Labelle & Anne Charbonneau

An in-depth genealogical biography of Guillaume Labelle and Anne Charbonneau, early settlers of Montréal and Île-Jésus in New France. This page examines their French origins, migration to Canada, marriage, landholdings, and descendants, documenting the beginnings of the Labelle family line in North America.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Guillaume Labelle & Anne Charbonneau

The Founding Couple of the Labelle Family in North America

Guillaume Labelle, son of Jean Labelle and Marie Loue, was born around 1649 in the parish of Saint-Éloi in Tonnetuit, Normandy, in northern France. Today, Tonnetuit—historically also written Tontuit or Tontuil—forms part of the commune of Saint-Benoît-d’Hébertot, in the department of Calvados, Normandy. The former parish church of Saint-Éloi was destroyed or demolished in 1830.

Located approximately 12 kilometres south of Honfleur and the English Channel, Saint-Benoît-d’Hébertot is a small rural commune with fewer than 500 residents, known as Bénédictains and Bénédictaines.

Location of Saint-Benoît-d'Hébertot in France (Mapcarta)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (December 2025)

Life in Tonnetuit was likely shaped by agriculture, parish routine, and the seigneurial system. Most boys contributed to farm labour from a young age, with little opportunity for formal schooling. Daily life was physically demanding, closely tied to the local community, and structured by the church calendar. Economic prospects were limited by land scarcity and inheritance practices that favoured older sons. Growing up amid the lingering instability and periodic hardship of the mid-17th century, Guillaume would have faced few avenues for advancement, making emigration to New France, where land and opportunity were more attainable, a plausible path as he approached adulthood.

Emigration to New France

Guillaume’s arrival in New France can most plausibly be placed in 1667. He does not appear in the 1666 or 1667 censuses, suggesting that he arrived after those enumerations were taken. He is, however, clearly present in Montréal by May 11, 1668, when he received the sacrament of confirmation from Monseigneur de Laval. Transatlantic crossings took several weeks and depended on the summer sailing season, making it impossible for him to have left France in the spring of 1668 and reached Montréal by early May. His confirmation therefore indicates that he was already in the colony by the previous year, supporting 1667 as the most likely year of arrival.

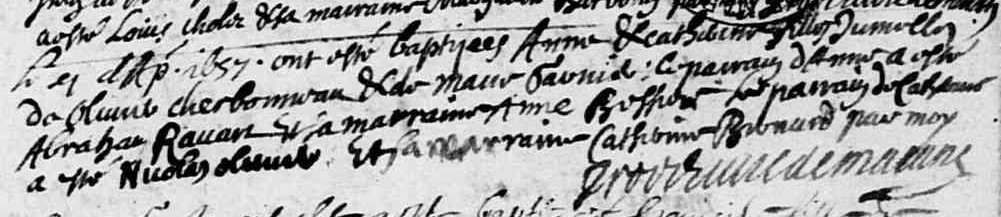

Anne Charbonneau, daughter of Olivier Charbonneau and Marie Marguerite Garnier, was baptized alongside her twin sister Catherine on April 11, 1657, in the church of Saint-Étienne in Marans, Aunis, France.

1657 baptism of Anne and Catherine Charbonneau (Archives de la Charente-Maritime)

Location of Marans in France (Mapcarta)

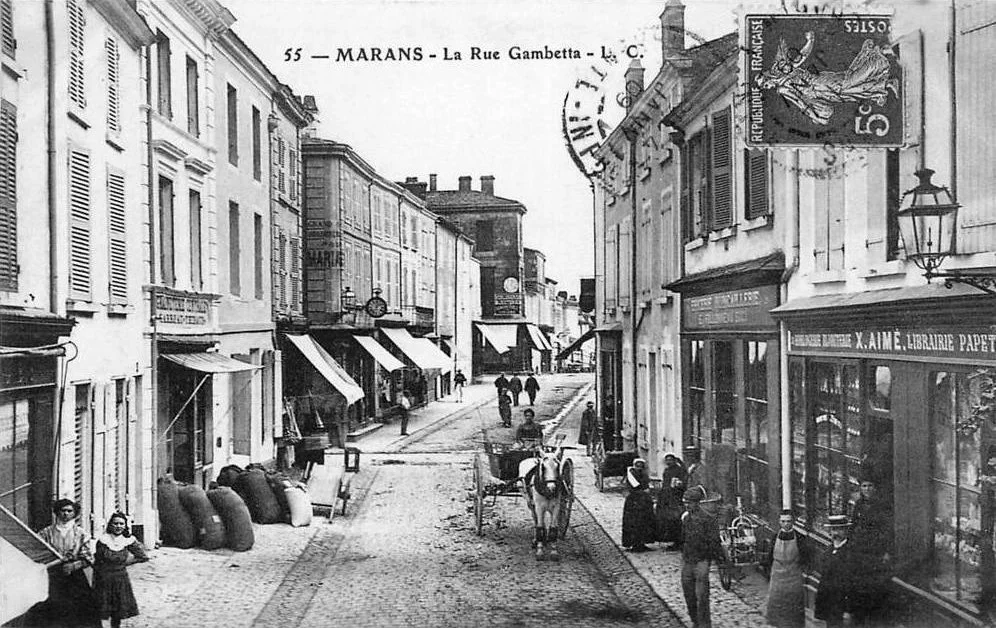

Located approximately 22 kilometres northeast of the port city of La Rochelle, Marans lies today in the department of Charente-Maritime. It is a rural town of fewer than 5,000 residents, known as Marandais and Marandaises.

Postcard of Marans, 1900 (Geneanet)

Postcard of Marans, 1909 (Geneanet)

A New Home in New France

When she was still a toddler, Anne’s parents decided to seek a better future by leaving France for Canada. In the spring of 1659, Olivier Charbonneau and his young family left Marans and travelled to La Rochelle, where they joined a group of labourers hoping to cross the Atlantic. Unable to pay their passage, Olivier turned to Jeanne Mance, who advanced the cost of the voyage and arranged for the family’s belongings to be secured in a sturdy chest. After several weeks of delay, their ship, the Saint-André, finally sailed in July. The crossing was marked by storms, illness, food shortages, and prolonged hardship at sea. In early September, the survivors reached Québec, and soon afterward continued on to Ville-Marie [Montréal], where Anne would spend her childhood in a small but growing colonial settlement.

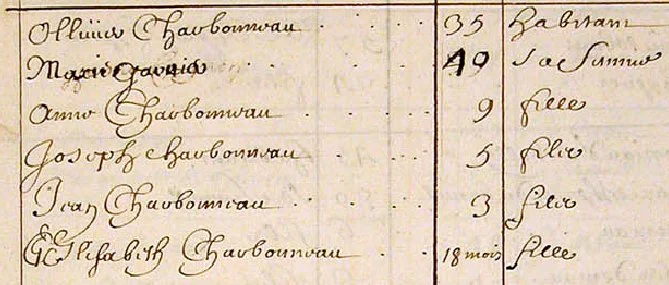

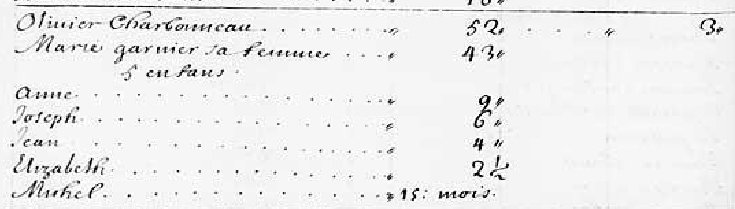

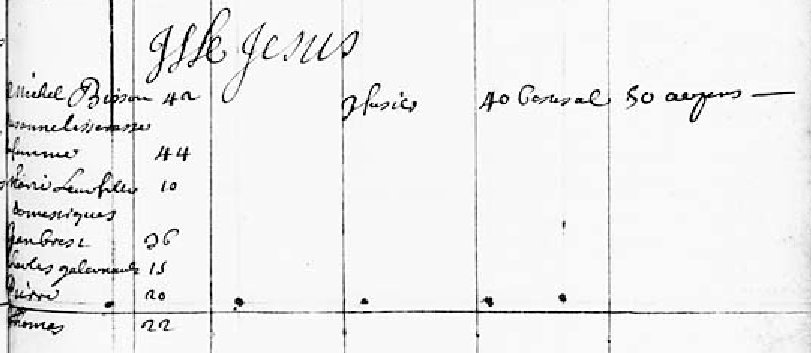

The Charbonneau family appears in the 1666 and 1667 censuses of New France, living in Montréal. Olivier and Marie were recorded with their children, including nine-year-old Anne, and were noted as holding three arpents of “valuable” land, meaning land that had been cleared or placed under cultivation.

1666 census of New France (Library and Archives Canada)

1667 census of New France (Library and Archives Canada)

Legal Age to Marry and Age of Majority

In New France, the legal minimum age for marriage was 14 for boys and 12 for girls. These requirements remained unchanged during the eras of Lower Canada and Canada-East. In 1917, the Catholic Church revised its code of canon law, setting the minimum marriage age at 16 for men and 14 for women. The Code civil du Québec later raised this age to 18 for both sexes in 1980. Throughout these periods, minors required parental consent to marry.

The age of majority has also evolved over time. In New France, the age of legal majority was 25, following the Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris). This was reduced to 21 under the British Regime. Since 1972, the age of majority in Canada has been set at 18 years old, although this age can vary slightly between provinces.

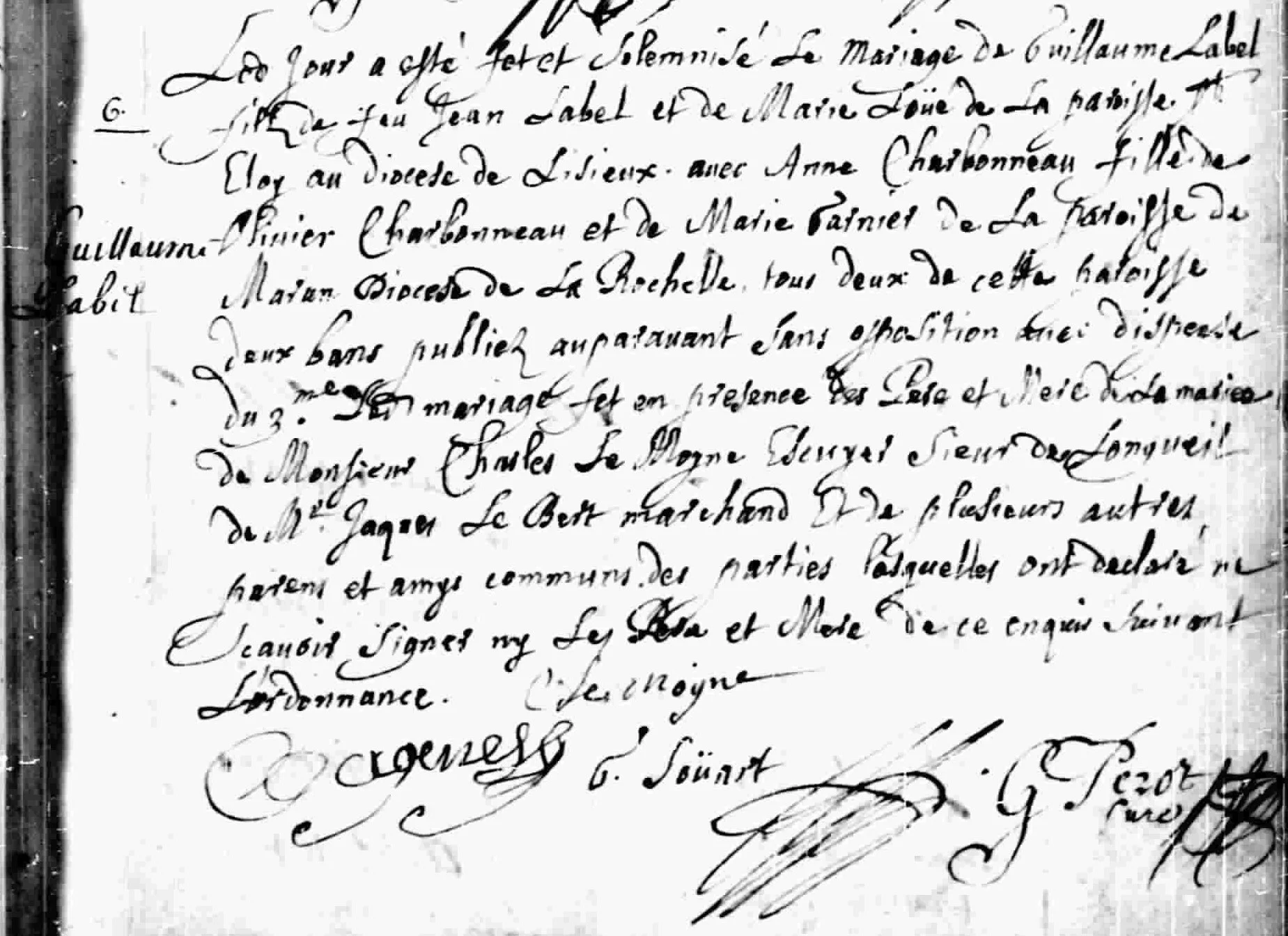

The contract identifies Guillaume as an habitant of the island of Montréal, “from the parish of St Eloy in Normandy near Lysieux, son of the late Jean Labelle and Marie Loue.” Anne is described as a resident of Montréal, the daughter of Olivier Charbonneau, an habitant, and Marie Garnier. The document was witnessed by a notable group of relatives, neighbours, and prominent figures. Guillaume’s witnesses were Jacques Leber, his wife Jeanne LeMoyne, and their son Louis Leber, as well as Jean Petit, tailor. Anne’s witnesses included her parents; her uncle Simon Cardinal (husband of Michelle Garnier); her uncle Pierre Goguet (husband of Louise Garnier); her cousin Jacques Cardinal; her cousin Mathurin Thibodeau (husband of Catherine Avrard); Marie Thibodeau, daughter of Mathurin and Catherine; Charles Le Moyne, sieur de Longueuil, and his wife Catherine Thierry dite Primeau; and François Dollier de Casson, Sulpician priest. The official witnesses were Jean Gervaise and François Bailly dit Lafleur.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (December 2025)

The contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. The dower was set at 300 livres, and Anne’s parents gifted the couple three blankets, four chickens, and 60 livres. Several of the witnesses signed the act, but neither the bride nor the groom was able to do so.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children. The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him.

The marriage ceremony took place the following day, November 23, 1671, in the Notre-Dame chapel in Montréal. Charles Le Moyne, sieur de Longueuil, and Jacques Leber served as witnesses, along with many relatives and friends.

1671 marriage of Guillaume and Anne (Généalogie Québec)

Guillaume and Anne had at least twelve children:

Antoine (1674–aft. 1681)

Marie Françoise (1676–1678)

Marie (1678–1702)

Charles (1679–1740)

Marie Madeleine (1681–1760)

Pierre (1684–1769)

Joseph (ca. 1686–1750)

Jacques (1688–1748)

Jean François (ca. 1690–1742)

Catherine (1692–1767)

Joachim (ca. 1695–1764)

Marie Angélique (1697–1772)

Land Transactions

Just six days after his wedding, Guillaume purchased a 60-arpent land concession in a location called “Bois-Brûlé” on the island of Montréal from Louis Marié dit Sainte-Marie for 150 livres. The concession measured three arpents of frontage, facing the St. Lawrence River, by 20 arpents deep. It bordered the concessions of joiner Claude Raimbault and a man named Lamothe. Guillaume agreed to pay the seigneurs an annual cens of six deniers for each of the 60 arpents, plus a rente of one and a half minots of wheat, due on the feast day of Saint Martin. The agreement was drawn up in the study of notary Bénigne Basset dit Deslauriers on the morning of November 29, 1671. The official witnesses were Jean Gervaise and François Bailly dit Lafleur. [Bois-Brûlé was a local place-name on the côte Saint-François in the east end of the island of Montréal (later associated with Longue-Pointe), named for land cleared by burning. In modern terms, it corresponds broadly to the Longue-Pointe / Anjou sector of Montréal.]

Guillaume was involved in two additional land transactions the following year. On the afternoon of November 30, 1672, he purchased another 60-arpent concession on côte Saint-François from surgeon René Sauvageau, sieur de Maisonneuve. Guillaume was described as an habitant residing on the island of Montréal. The concession measured three arpents of frontage, facing the St. Lawrence River, by 20 arpents deep, bordering the concession of Claude Desjardins. The land included “a cabin covered with planks and a shed made of stakes in the ground.” Guillaume agreed to pay the seigneurs an annual cens of six deniers per arpent, along with a rente of three capons, payable on the feast day of Saint Martin. The purchase price was 500 livres, of which 55 livres were to be paid in “one hundred good covering planks.” Notary Basset drafted the agreement in Montréal. Sauvageau signed the act; Guillaume could not.

Four days later, on December 4, 1672, Guillaume and Louis Marié dit Sainte-Marie cancelled their earlier agreement concerning the Bois-Brûlé concession. The cancellation was recorded by notary Basset in Montréal.

Guillaume returned to notary Basset’s study on October 21, 1674, alongside René Sauvageau, from whom he had purchased land two years earlier. Having failed to meet his financial obligations, Guillaume faced eviction. He instead offered to clear three arpents of trees from Sauvageau’s land across from Pointe-aux-Trembles. The two men reached an agreement allowing Guillaume to remain on the property until 1676, provided he continued to fell trees as required.

Île-Jésus

The Labelle family’s connection to Île-Jésus began in 1675. On October 29, Guillaume and his father-in-law, Olivier Charbonneau, entered into a three-year lease for the seigneurial farm on Île-Jésus, an agreement drawn up by notary Thomas Frérot on behalf of Monseigneur de Laval. At the time, the farm already included 45 arpents of cleared and cultivated land. In exchange for the lease, Guillaume and Olivier committed to delivering 60 minots of wheat and 20 minots of peas each year, while the seigneur supplied four draft oxen and poultry. The two men worked the farm until the lease expired in October 1678.

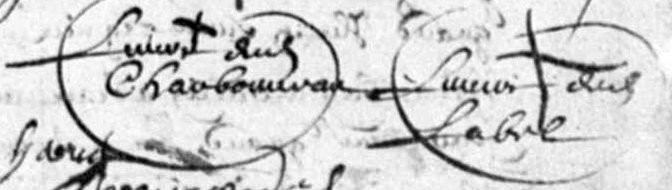

Marks of Guillaume and Olivier on the 1675 lease (FamilySearch)

Three years after first settling on Île-Jésus, on August 7, 1678, Guillaume received a 60-arpent land concession in the seigneurie du Bon Pasteur. The act was drawn up by notary Thomas Frérot on behalf of Marguerite Bourgeoys and the Congrégation Notre-Dame de Montréal, owners of the seigneurie. The wooded concession measured three arpents of frontage on the Rivière des Prairies by 20 arpents deep and bordered the land of his brother-in-law Joseph Charbonneau. Guillaume agreed to pay an annual rente of three livres, along with two sols of cens and 22 minots of wheat, due on All Saints’ Day (November 1).

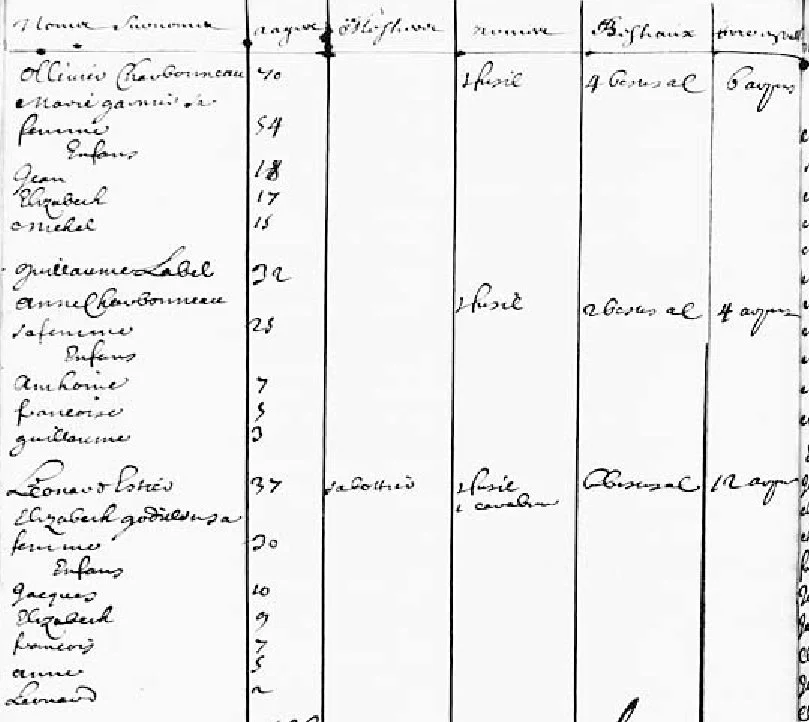

In 1681, another census was undertaken in New France. It shows that only four families were living on Île-Jésus: those of Guillaume Labelle, Olivier Charbonneau, Michel Buisson, and Léonard Éthier. Guillaume, aged 32, and his wife Anne, 25 [sic], were living on the island with their three children: Antoine, Françoise, and Guillaume [sic; likely Marie]. The household owned four arpents of “valuable” land, meaning land that had been cleared or placed under cultivation, as well as one gun and two head of cattle.

Île-Jésus households in the 1681 census (Library and Archives Canada)

On September 14, 1682, master candle-maker Gilles Carré sold Guillaume seeds of wheat. In return, Guillaume agreed to deliver [nine?] minots of wheat to Carré on the next All Saints’ Day.

Conflict with the Iroquois

From the late 1680s through the end of the century, the French settlements on Montréal, Île-Jésus, and their hinterlands lived in an atmosphere of intermittent violence and shifting diplomacy with the Iroquois Confederacy (particularly the Mohawk). Although earlier peace agreements in the 1660s and early 1670s had brought a measure of calm, hostilities intensified again in the 1680s as competition over the fur trade and territorial influence in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence region drew the Iroquois into renewed raiding and warfare against French colonial communities and their Indigenous allies. One of the most dramatic of these assaults was the Lachine massacre of August 1689, when a large band of Mohawk warriors attacked the farming settlement near Montréal, killing residents, taking captives, and burning homes. While not every year saw open battle, the threat of raid or reprisal shaped daily life for habitants and soldiers alike throughout the 1690s.

By the late 1690s, however, the climate began to shift. Broader developments in Europe, including the Peace of Ryswick (1697), reduced external pressures on Indigenous alliances, and colonial and Indigenous leaders increasingly saw negotiated peace as preferable to endless warfare. Diplomatic efforts involving French officials, representatives of the Iroquois Confederacy, and leaders of many other First Nations culminated in the Great Peace of Montréal, signed on August 4, 1701. This landmark treaty brought a formal end to decades of intermittent conflict associated with the Beaver Wars in the St. Lawrence Valley and established frameworks for peaceful coexistence and alliance that allowed communities on Île-Jésus, Montréal, and beyond to pursue settlement, agriculture, and commerce with greater security.

"The Lachine Massacre," by Jean-Baptiste Lagacé (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

During the 1690s, the Labelle family likely left Île-Jésus due to the ongoing Iroquois conflict and the dangers of remaining in a small, undefended seigneurie. Most other residents of Île-Jésus appear to have done the same. In October 1692, Guillaume spent the entire month at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Québec, suggesting that the family was likely living in the area at that time.

Guillaume’s name also appears as an employee in the account books of the clergy who operated a farm at Saint-Joachim, near Beaupré, east of Québec. These were the same clergy—the Séminaire de Québec—who owned the seigneurie of Île-Jésus. After the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701, the Labelle family returned to their land on Île-Jésus.

On the afternoon of February 7, 1707, Guillaume and Anne waived their rights to a portion of land on Île-Jésus that Anne had inherited from her father, transferring it to her brother Jean Charbonneau. In exchange, Jean agreed to assume his parents’ outstanding debts and all future seigneurial obligations associated with the land. The agreement was drawn up by notary Nicolas Senet dit Laliberté in Guillaume and Anne’s home.

Death of Guillaume Labelle

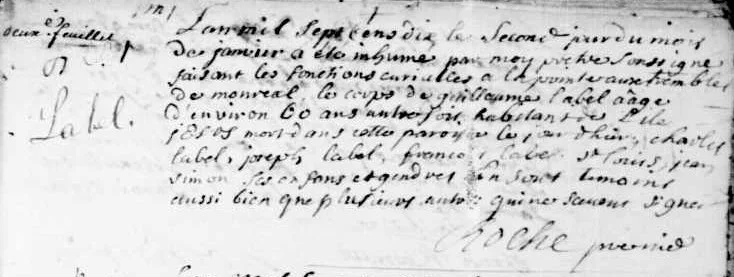

Guillaume Labelle died at the age of approximately 61 on January 1, 1710, in Pointe-aux-Trembles. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Enfant-Jésus. His sons Charles, Joseph, and Jean François attended the burial, as did his sons-in-law Louis Filiatrault dit St-Louis and Jean Simon dit Léonard, among many others. The burial record states that Guillaume was about 60 years old and identifies him as a former habitant of Île-Jésus.

1710 burial of Guillaume (Généalogie Québec)

Second Marriage of Anne Charbonneau

On the afternoon of February 15, 1711, notary Nicolas Senet dit Laliberté drew up a marriage contract between Anne Charbonneau and Pierre Guédon (or Guindon) at Anne’s home on Île-Jésus. Pierre was the 48-year-old widower of Catherine Bresa dite Lafleur and, like Anne, a resident of the island; Anne was 53. Pierre’s witness was Pierre Nadon. Anne’s witnesses included her children Pierre, Joseph, Jacques, and Marie Madeleine (with her husband Louis Filiatrault dit St-Louis); her daughters-in-law Jeanne Boulard and Marguerite Lamoureux; her sister Elisabeth (with her husband Joseph Barbeau); and her niece Marie Cyr (with her husband François Coron).

The contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. The pre-fixed dower was set at 150 livres. The official witnesses were Léonard Simon and Pierre Drouillard, who signed the act, along with Filiatrault dit St-Louis and the notary. The bride and groom, as well as the remaining witnesses, declared that they did not know how to sign.

On the afternoon of June 3, 1716, Anne and her son Pierre exchanged their adjoining plots of land on Île-Jésus. The agreement was drawn up by notary Michel Lepailleur de LaFerté in his Montréal study.

On March 8, 1724, Anne and Pierre transferred a plot of land on Île-Jésus to Anne’s surviving children, her grandson Jean Migneron, and Jacques Desnoyers, widower of her granddaughter Marie Anne Migneron. The land measured three arpents of frontage by 20 arpents deep and adjoined the lands of Pierre Labelle and notary François Coron. It derived from Anne’s community of property with her late husband Guillaume Labelle. In return, the children and grandchildren agreed to provide Anne with 15 minots of wheat annually, beginning the following year and continuing until her death. Upon her death, they also undertook to have four masses each said for the repose of her soul. The agreement was drawn up by notary François Coron in his study on Île-Jésus.

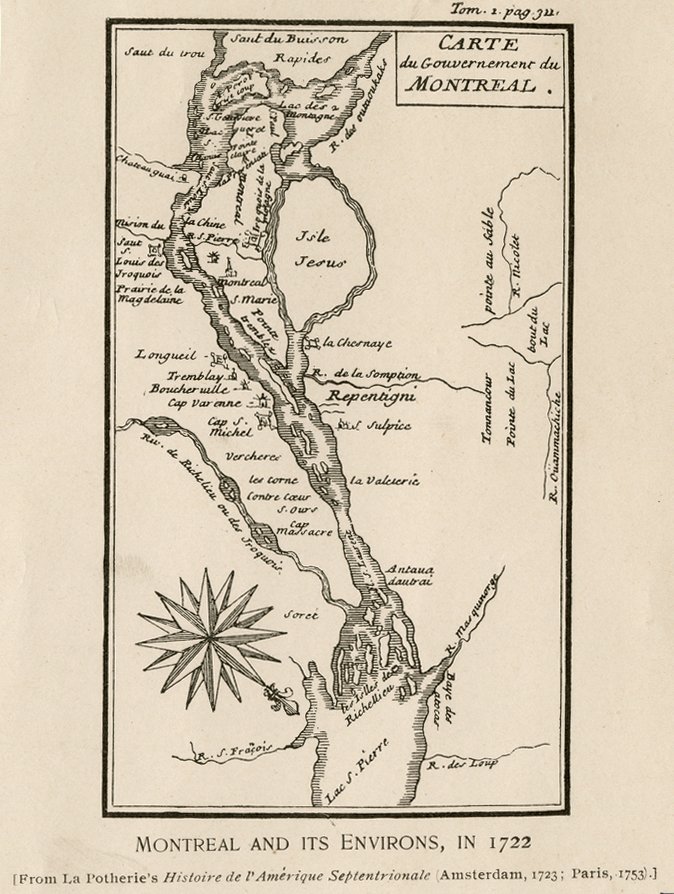

Map of the Government of Montréal showing Île-Jésus, 1722 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

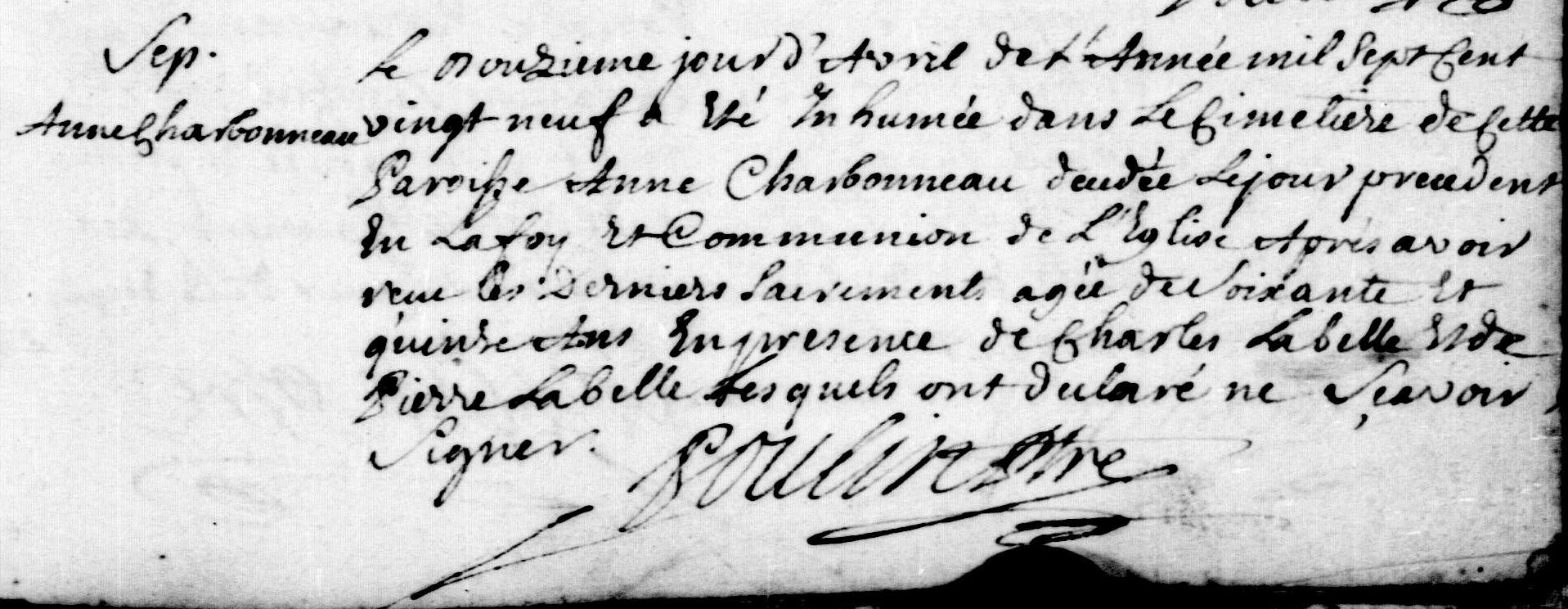

Death of Anne Charbonneau

Anne Charbonneau died at the age of 72 on April 11, 1729. She was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-François-de-Sales on Île-Jésus. Her sons Charles and Pierre attended the burial. [The burial record incorrectly indicates that she was 75 years old.]

1729 burial of Anne (Généalogie Québec)

The Quiet Foundations of a Lasting Legacy

Guillaume Labelle and Anne Charbonneau stand at the beginning of a family line that would spread across North America over the centuries that followed. Their lives reflect the realities of early New France: migration across the Atlantic, settlement on contested land, years shaped by work, family responsibility, and uncertainty, and a steady commitment to building a future in a new colony. Through marriage, landholding, and the raising of a large family, they laid durable foundations on Montréal and Île-Jésus. From this single household grew generations of descendants, making Guillaume and Anne not only early settlers of New France, but the shared ancestors of all Labelles in North America.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“GG 2/Marans/Collection communale/Baptêmes/1623–1661," digital images, Archives de la Charente-Maritime (http://www.archinoe.net/v2/ark:/18812/dacb270dd3fc14abf93598aabdbc30d4 : accessed 18 Dec 2025), baptism of Anne Cherbonneau, 11 May 1657, Marans (St-Etienne), image 74 of 113.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/47362 : accessed 18 Dec 2025), marriage of Guillaume Labelle and Anne Charbonneau, 23 Nov 1671, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/11962 : accessed 19 Dec 2025), burial of Guillaume Labelle, 2 Jan 1710, Montréal, Pointe-aux-Trembles (St-Enfant-Jésus); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/22670 : accessed 19 Dec 2025), burial of Anne Charbonneau, 12 Apr 1729, Laval (St-François-de-Sales); citing original data: Institut généalogique Drouin.

"Registre des confirmations 1649-1662," digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/membership/fr/fonds-drouin/REGISTRES : accessed 18 Dec 2025), confirmation of Guillaume la Belle, Montréal, 11 May 1668; citing original data: Registre des confirmations, Diocèse de Québec, Registres du Fonds Drouin.

“Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968,” digital images, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_31480073?usePUB=true&_phsrc=uiD2634 : accessed 19 Dec 2025), Hôtel-Dieu patient list, entry for Guillaume Labelle, 1 Oct 1692; citing original data: Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin.

“Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-ND5L?cat=koha%3A426906&i=784&lang=en : accessed 18 Dec 2025), marriage contract of Guillaume Labelle and Anne Charbonneau, 22 Nov 1671, images 785-787 of 3072; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NDPD?cat=koha%3A426906&i=804&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), sale of a land concession by Louis Marye dit Ste Marie to Guillaume La Belle, 29 Nov 1671, images 805-807 of 3072; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NCH4?cat=koha%3A426906&i=1444&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), sale of a land concession by René Sauvageau to Guillaume Labelle, 30 Nov 1672, images 1445-1447 of 3072; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NCQC?cat=koha%3A426906&i=1458&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), cancellation of a land sale agreement between Louis Marie dit Ste Marie and Guillaume Labelle, 4 Dec 1672, image 1459 of 3072; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1657-1699 // Bénigne Basset," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-NFM5?cat=koha%3A426906&i=2149&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), agreement between René Sauvageau and Guillaume Labelle, 21 Oct 1674, images 2150-2152 of 3072; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1669-1678 // Thomas Frérot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-D3WX-V?cat=koha%3A644971&i=883&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), farm lease by François de Laval to Guillaume Label and Olivier Charbonneau, 29 Oct 1675, images 884-889 of 3153; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1669-1678 // Thomas Frérot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-D376-S?cat=koha%3A644971&i=904&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), land concession by the Congrégation Notre-Dame de Montréal to Guillaume Label, 7 Aug 1678, images 905-907 of 3153; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1677-1696 // Claude Maugue," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-GS6X-3?cat=koha%3A427707&i=2436&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), sale of wheat seeds to Guillaume Label by Gilles Carré, 14 Sep 1682, image 2437 of 2531; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Actes de notaire, 1704-1731 // Nicolas Senet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-W37Q-B?cat=koha%3A529332&i=2564&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), waiver of inheritance rights by Guillaume Label and Anne Charbonnot in favour of Jean Charbonnot, 7 Feb 1707, images 2565-2566 of 3215; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1704-1731 // Nicolas Senet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTW-ZSWF-X?cat=koha%3A529332&i=18&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), marriage contract of Pierre Guesdon and Anne Charbonnot, 15 Feb 1711, images 19-20 of 3212; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1701-1732 // Michel-Laferté Lepailleur," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5K-MVXC?cat=koha%3A538127&i=1637&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), land exchange between Anne Charbonneau and her son Pierre Labelle, 3 Jun 1716, image 1638 of 3111; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1721-1732 // François Coron," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5V-ZSVC?cat=koha%3A481227&i=691&lang=en : accessed 19 Dec 2025), agreement between Anne Charbono and Pierre Guindon, and Anne’s children and grandchildren, 8 Mar 1724, images 692-693 of 3191; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 18 Dec 2025), household of Ollivier Charbonneau, 1666, Montreal, page 125 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 18 Dec 2025), household of Olivier Charbonneau, 1667, Montreal, page 176 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 19 Dec 2025), household of Guillaume Label, 14 Nov 1681, Île-Jésus, page 128 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/3815 : accessed 18 Dec 2025), dictionary entry for Guillaume LABELLE and Anne CHARBONNEAU, union 3815.

Gérard Lebel, Nos Ancêtres 10 (Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, Revue Sainte Anne de Beaupré, 1985), 39-44.

Gérard Lebel, Nos Ancêtres 14 (Ste-Anne-de-Beaupré, Revue Sainte Anne de Beaupré, 1987), 116-119.

Archange Godbout, Les passagers du Saint-André : La Recrue de 1659 (Société généalogique canadienne-française, Montréal, 1964), page 9.

Cornelius J. Jaenen and Andrew McIntosh, "Great Peace of Montreal, 1701," The Canadian Encyclopedia (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/peace-of-montreal-1701 : accessed 19 Dec 2025), article published 7 Feb 2006, last edited 13 Nov 2019.

Jacqueline Sylvestre, "L’âge de la majorité au Québec de 1608 à nos jours," Le Patrimoine, Feb 2006, volume 1, number 2, page 3, Société d’histoire et de généalogie de Saint-Sébastien-de-Frontenac.

François Plourde, "Le ruisseau Molson au début de la colonisation de la Longue-Pointe, deuxième partie," Patrimoine naturel de l’est de Montréal (https://ruisseaumolsonreferences.blogspot.com/2018/06/le-ruisseau-molson-au-debut-de-la_11.html : accessed 19 Dec 2025).