Adrien Isabel & Catherine Poitevin

Discover the story of Adrien Isabel/Isabelle & Catherine Poitevin/Potvin, early settlers of New France. From Normandy peasant and Parisian Fille du roi to Île-d'Orléans landowners.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Adrien Isabel & Catherine Poitevin

Founders of the Isabelle Line in North America

Adrien Isabel (or Isabelle), son of Jean Isabel and Marie Adam, was born around 1638 in the parish of Saint-Étienne in Reux, Normandy, France. He had two known brothers: Jean (date of birth unknown) and Michel (born in 1645).

Location of Reux in France (Mapcarta)

Located in the present-day department of Calvados about 70 kilometres west of Rouen, Reux is a small rural commune with fewer than 500 inhabitants, called Reuxois.

The church of Saint-Étienne in Reux where Adrien was likely baptized exemplifies the architectural evolution typical of Norman parish churches. The structure blends Romanesque and Gothic elements: its square tower with carved modillons represents the oldest section, dating to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, while the main body was constructed during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and features a Renaissance west portal. The timber-framed porch and ancient yews distinguish the exterior, and the building commands views over the Touques valley with the austere, substantial character common to rural churches in the region. It received historic monument protection in 2015.

Église Saint-Étienne in Reux (photos by ChBougui, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Life in Rural Normandy

Economic hardship in Adrien's homeland helps explain why he would eventually seek opportunities across the Atlantic. In the mid-seventeenth century, Reux was a small agricultural village in Normandy's Pays d'Auge. Daily life revolved around subsistence farming: peasants cultivated cereals, tended livestock, and owed dues to seigneurial landlords and tithes to the parish church. The region was still recovering from the economic stagnation and population losses of the late Middle Ages, compounded by outbreaks of plague (notably in 1622 and 1636) and the devastations of the Thirty Years' War, which brought taxation and troop movements even into Normandy. Social mobility was limited—land was scarce, inheritances divided properties into ever-smaller plots, and younger sons of farming families often had little chance to establish themselves locally.

For the Isabel brothers, New France represented opportunity. The French crown and trading companies were actively recruiting settlers to strengthen the colony against English and Dutch rivals and to supply manpower for fur-trade networks. Inducements included paid passages, land grants (concessions in seigneuries), and sometimes financial aid for marriage. Ports such as Honfleur, Dieppe, and La Rochelle provided the embarkation points for hundreds of migrants, and families from the Calvados region are well represented among early colonists. Economic pressures at home, limited prospects for inheritance, and the lure of land ownership and advancement overseas all helped push young men to "take service" in Canada.

The exact date of Adrien's departure from France is unknown, but he was in Canada by 1664. His brother Michel also emigrated to New France, first mentioned in the colony in 1666.

A Shaky Start in New France

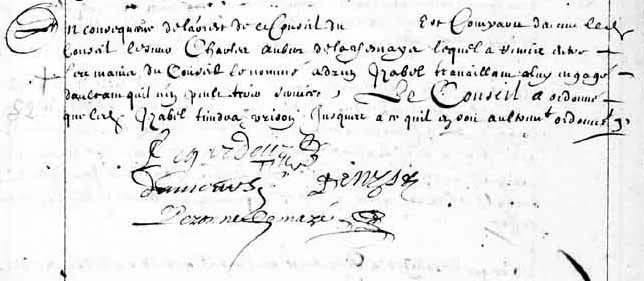

The transition from Normandy to the New World was far from smooth for Adrien. He likely arrived in Canada as an engagé (indentured servant), with employment already secured with Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye, a wealthy merchant and seigneur. However, their working relationship appears to have soured for unknown reasons. On January 7, 1665, a Sovereign Council ruling ordered that Adrien be imprisoned at the request of his master, de La Chesnaye, who claimed he could not be of service to him. De La Chesnaye handed Adrien over to the authorities, with the council ordering him kept in prison until otherwise ordered.

This legal trouble reveals the precarious position of engagés in New France. Men such as Adrien signed binding contracts, often for three years, in exchange for passage to Canada, food, lodging, and modest wages. In return, they were expected to provide steady and obedient labour in whatever tasks their employer required, whether agricultural work, construction, or service in trade. Any refusal or inability to perform these duties could quickly escalate into a legal matter, since the colony's survival relied heavily on a small pool of workers. By stating that he could "draw no service" from Isabel, Aubert de La Chesnaye effectively accused his servant of failing to meet the obligations of his contract—whether through refusal, negligence, conflict, or other behaviour that made him unproductive.

The Sovereign Council’s decision to imprison Isabel until further notice demonstrates the strict enforcement of authority and discipline in the young colony. Labour shortages meant that every man's work was deemed vital, and open resistance could not be tolerated. Adrien's case illustrates the vulnerability of engagés, who, once transported to Canada, had little recourse if disputes arose with their employers. Their contracts placed them in a position of dependence, and in conflicts such as this one, the courts almost invariably sided with the master.

1665 ruling ordering the imprisonment of Adrien Isabel (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

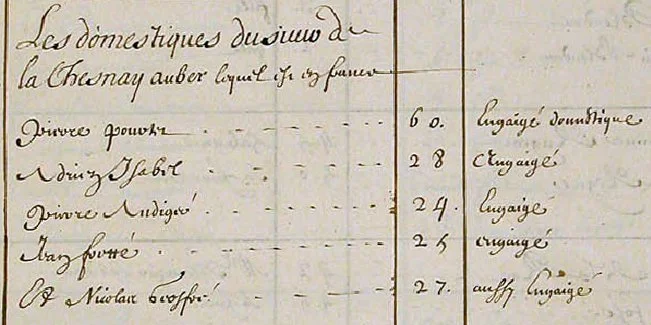

Despite this rocky beginning, Adrien's situation eventually stabilized. While the length of his imprisonment is unknown, he appears to have reconciled with his master. By 1666, "Adrien Izabel" was recorded as an engaigé in de La Chesnaye's household in Québec.

1666 census of New France listing the servants of de La Chesnaye (Library and Archives Canada)

Land Concession

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (September 2025)

Adrien's fortunes began to improve significantly the following year when he gained his independence from servitude. On June 22, 1667, Adrien received a land concession located on the south side of Île-d'Orléans from François de Laval, the first bishop of New France. Measuring three arpents of frontage, the land bordered the St. Lawrence River, the lots of Estienne Bellinier and Pierre St-Denis Jr., and "the path which will cross the island from point to point." Adrien agreed to pay 20 sols in rente and 12 deniers in cens per arpent of frontage on each feast day of Saint Martin (November 11, plus three live capons (or 30 sols each, at the discretion of the seigneur). Adrien also promised to grind his grain at the seigneurial mill. He did not sign the concession document, drawn up by notary Paul Vachon.

Rather than immediately settling on his newly acquired property, Adrien focused on earning money through contract work. On October 30, 1667, he agreed to clear land on the côte de Lauson for Étienne Landeron for 70 livres, with the agreement describing him as a resident of côte de Lauson. Notably, he was able to sign this contract.

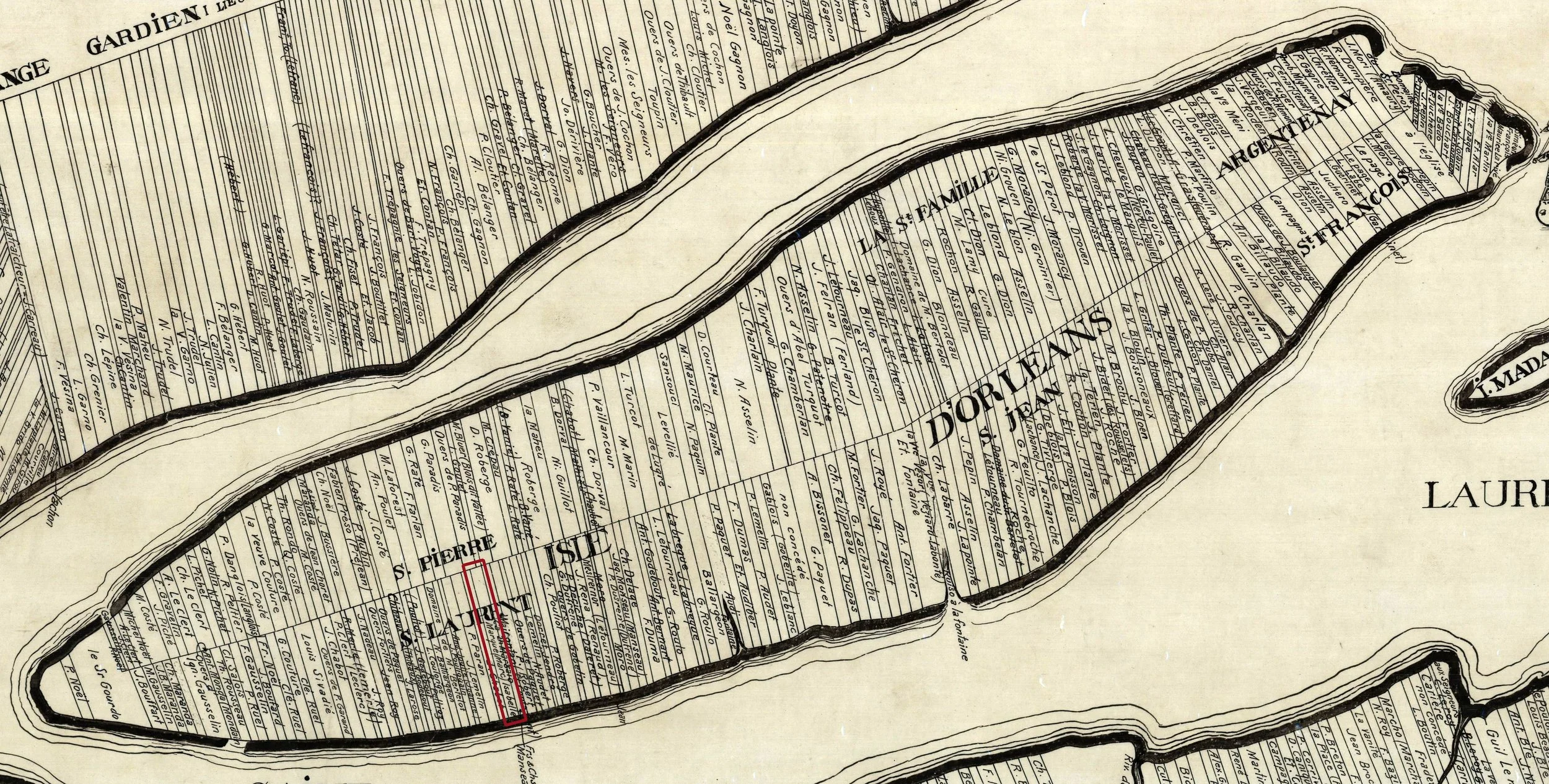

A map of Île-d’Orléans drawn up in 1709 by Gédéon de Catalogne and Jean-Baptiste Decouagne shows Adrien’s land concession, passed down to his son Marc after his death.

1709 map of Île-d’Orléans, with the Isabel land in red (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Catherine Poitevin, daughter of Guillaume Poitevin and Françoise Macré, was born around 1641 in the parish of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs in Paris, France.

Catherine’s mother’s name remains uncertain since her baptism record no longer exists. Her surname appears variously as Caillebries (first marriage contract), Macré (first marriage record), and McRae (according to the PRDH database).

The parish of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs was located just north of the medieval walls of Paris, in today’s 3rd arrondissement. Originally founded as a chapel in the twelfth century by the Benedictine monks of the neighbouring Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs, it grew into a substantial parish church over the following centuries. By the seventeenth century it was one of the larger parishes of Paris, serving artisans and tradesmen in a rapidly urbanizing district. The church itself combined Gothic and Renaissance phases of construction, with major works continuing into the early modern period.

Church of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs, 1630 drawing by Étienne Martellange (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

In the late 1660s, Catherine was recruited to emigrate to New France as a Fille du roi. She arrived in Canada in 1669, though her exact arrival date and ship remain unknown.

"The Arrival of the French Girls at Quebec," watercolour by Charles W. Jefferys (Wikimedia Commons)

Marriage and Children

On September 28, 1669, notary Romain Becquet drew up a marriage contract between Adrien and Catherine. Adrien was about 31 years old, described as a resident of Île-d’Orléans, the son of Jean Isabel and Marie “Adan” from the parish of “Renon.” Catherine was about 28, the daughter of Guillaume “Potevin” and Françoise “Caillebries,” from the parish of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs in Paris. The contract followed the norms of the Coutume de Paris. Adrien endowed his future wife with a customary dower of 300 livres [the dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife should she outlive him]. For her part, Catherine brought goods valued at 500 livres to the marriage, half of which would enter the community. The couple also received "the sum of 50 livres that His Majesty gave them in consideration of their marriage"—a sum typically given to Filles du roi upon their wedding.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. When a couple married, whether or not they had a marriage contract, they were subject to the "community of goods," meaning all property acquired during marriage by either spouse became communal. Upon the parents' death (assuming the couple had children), community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. When the community dissolved due to one spouse's death, the surviving spouse received half the community property, with the other half divided equally among the children. Upon the surviving spouse's death, their share was then divided equally among the children. Inventories were drawn up after a death to itemize all goods within the community.

The contract was signed in the home of Dame Bourdon (Anne Gasnier, wife of Jean Bourdon), who was responsible for recruiting and housing the Filles du roi in Québec. Both Adrien and Catherine signed the contract, alongside several other witnesses.

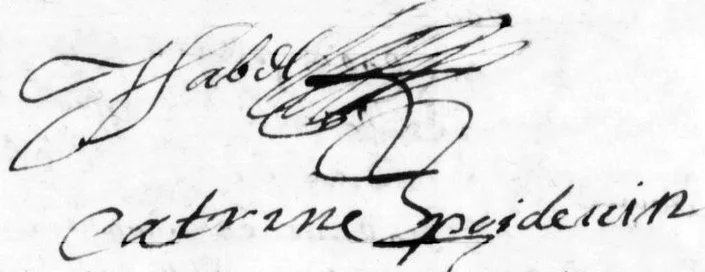

Signatures of Adrien and Catherine in 1669

Twelve days later on October 10, 1669, Adrien and Catherine married in the parish of Sainte-Famille on Île-d’Orléans. This record correctly identifies Adrien’s place of origin as Reux, and his mother’s name as Adam. Michel Isabel, Adrien’s brother, was present at the ceremony, as was Antoine Cassé.

Adrien and Catherine had four children, all baptized in the parish of Sainte-Famille:

Adrien (1670–1670)

Jean Pierre (1672–aft. 1681)

Marc (1674–1730)

Catherine (1676–aft. 1681)

Until his death, no other notarial or court documents mention Adrien.

Death of Adrien Isabel

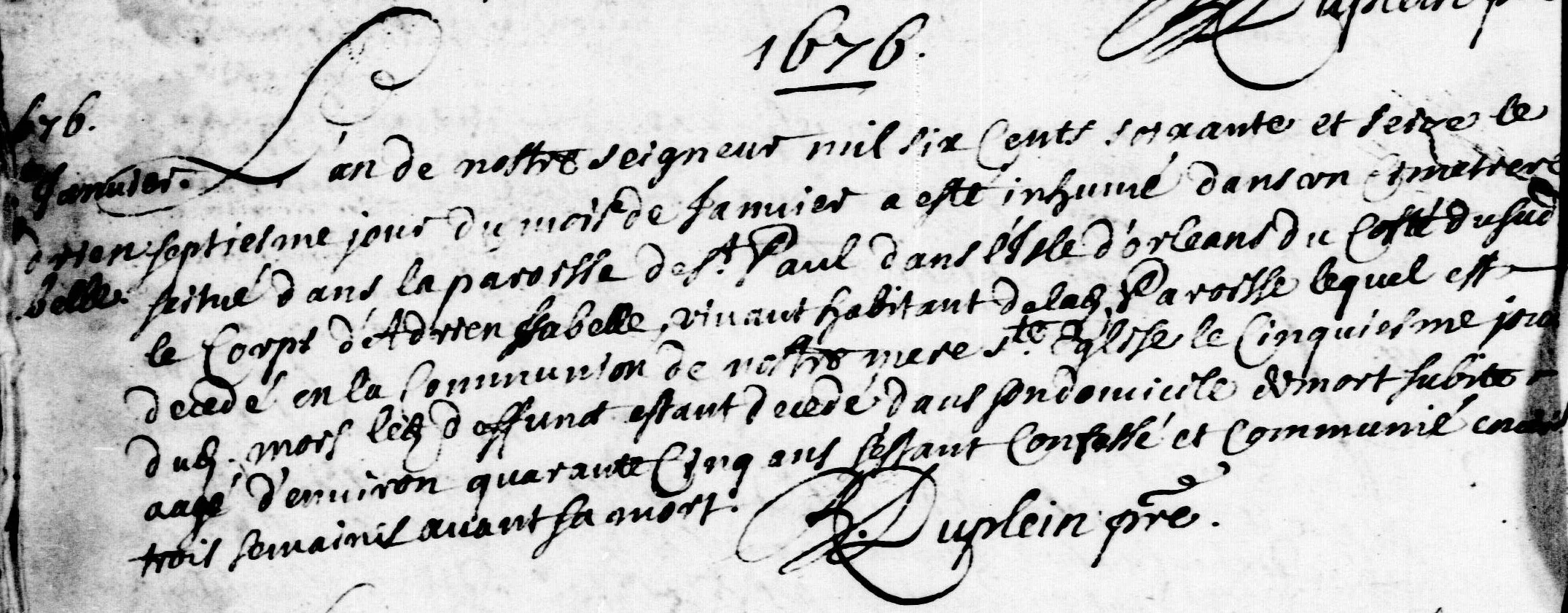

Adrien's life in New France ended abruptly when he died on January 5, 1676, at about 38 years of age. He was buried two days later in the parish of Saint-Paul on Île-d’Orléans. [The burial record erroneously states he was about 45.]

The translated burial record provides details about his final days:

“In the year of our Lord one thousand six hundred and seventy-six on the seventh day of January was buried in a cemetery located in the parish of Saint-Paul on Île-d'Orléans on the south side, the body of Adrien Isabelle, an habitant of the said parish, who died in communion with our Holy Mother Church on the fifth day of the said month, the said deceased having died suddenly at his home at the age of about forty-five, having confessed and received communion [illegible] three weeks before his death.”

1676 burial of Adrien Isabel (Généalogie Québec)

Following colonial custom, an inventory of Catherine and Adrien's community of goods was drafted by notary Paul Vachon on June 20, 1676. The 10-page document enumerates all of the couple's possessions, including the Île-d'Orléans property (where 10 arpents of land had been cleared) and a small house measuring 14 feet wide. [Unfortunately, the images of Vachon's documents at FamilySearch are rather blurry, and the document is missing from Vachon's inventory at BAnQ (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec).]

A Second Marriage for Catherine

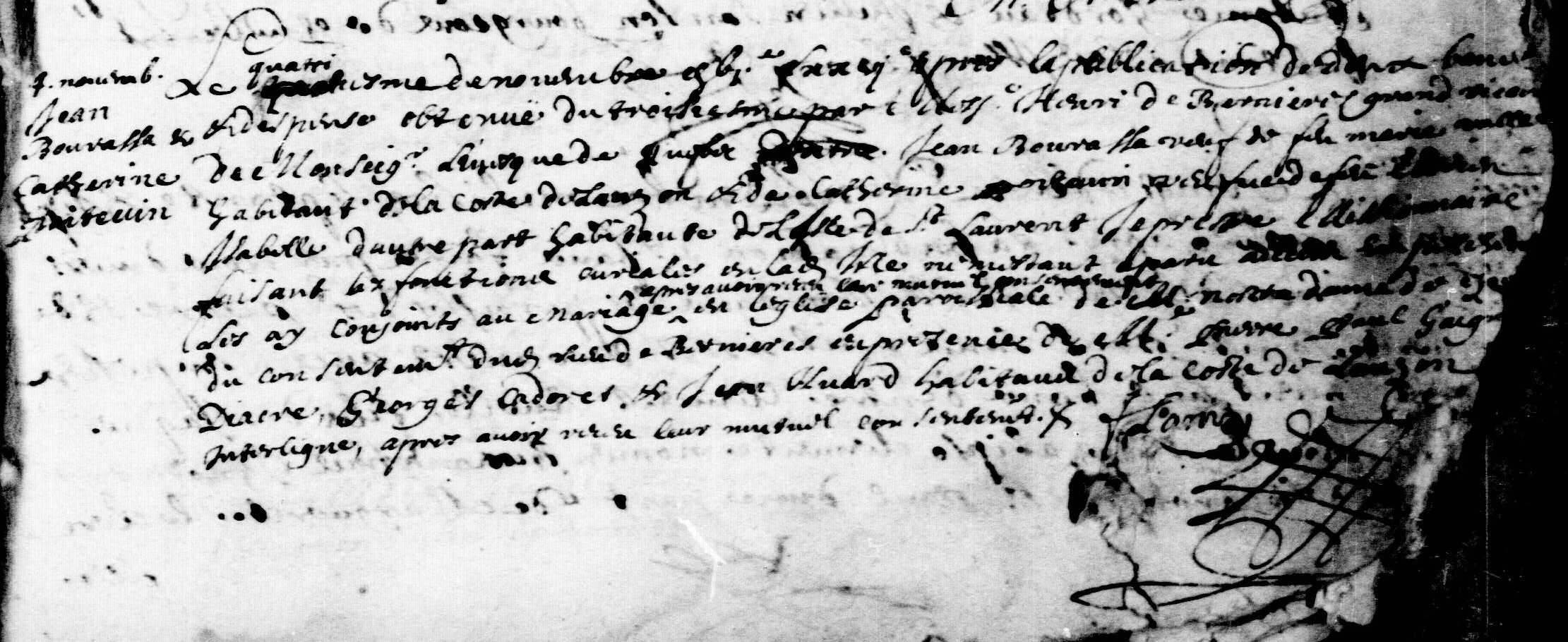

On October 25, 1676, notary Gilles Rageot drafted a marriage contract between Catherine and Jean Bourassa. He was the 42-year-old widower of Marie Pierrette Vallée and a resident of the côte de Lauson. She was approximately 35, a resident of the parish of Saint-Paul on Île-d’Orléans. Catherine signed the document in a shaky hand.

[Although Catherine “signed” her name on several documents in New France, the evidence suggests that she had only learned to reproduce her signature rather than being fully literate. Her handwriting is unsteady, and the spelling of her name varies from one document to the next, indicating that she likely could not read or write beyond this basic ability. In the seventeenth century, this was not unusual; many women (and men) in the colony were taught only to make a recognizable mark of their name, while broader literacy skills remained rare.]

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with ChatGPT (September 2025)

Ten days later on November 4, 1676, Catherine and Jean were married in the parish of Notre-Dame in Québec. Their witnesses were Pierre Paul Gaignon [Gagnon], Georges Cadoret, and Jean Huard.

1676 marriage of Jean Bourassa and Catherine Poitevin (Généalogie Québec)

Catherine and her children moved to live with her new husband on the côte de Lauson. In the decade following her marriage, she had four more children with Jean: René, Marie Anne, Marie Jeanne, and François.

The couple also managed Catherine's inheritance from her first marriage. On September 8, 1680, Catherine and Jean leased the Isabel land on Île-d'Orléans to Jean Jouanne, in a notarial record penned by Pierre Duquet de La Chesnaye.

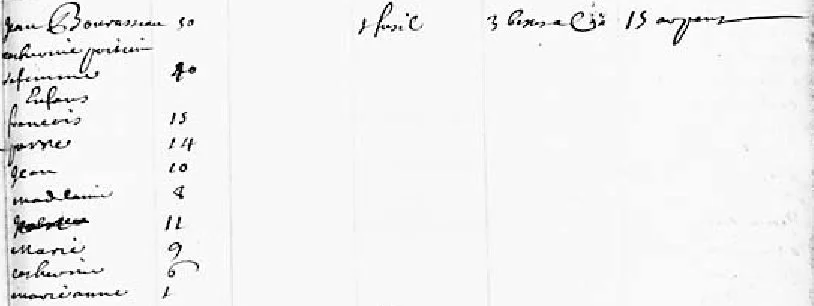

By 1681, the blended family was well-established. Catherine and Jean appeared in the New France census living in the seigneurie of Lauson with their eight children. They owned 15 arpents of “valuable” land (cleared and under cultivation), three head of cattle and one gun.

1681 census of New France for the “Bourasseau” family (Library and Archives Canada)

Catherine’s Final Years

Advancing age brought increasing hardships for the elderly couple. On June 15, 1711, Catherine and Jean gave their son François a plot of land located in the seigneurie of Lauson, which came from the community of goods between Jean and his first wife. The land measured four arpents of frontage, facing the St. Lawrence River, by 40 arpents deep. It included a "small half-timbered house measuring fifteen feet wide by eighteen feet long, covered with planks, and half a barn shared with [Louis] Marchand, with an ox, a cow, a heifer, and a two-year-old bull, two pigs for wintering, and the few pieces of furniture and utensils that remain, having burned down last year."

This donation, recorded by notary Louis Chambalon, reveals the harsh realities facing the aging couple. The document indicates that Jean, considering “his advanced age,” and Catherine, “who for several years has been severely disabled and deprived of her sight,” could no longer maintain the land, which Jean called “very unproductive, of little value and subject to thirty livres of rent, in addition to the cens and seigneurial rentes.” In exchange for the property, François agreed to pay all cens and rentes going forward and to feed, house, clothe, and care for his parents "in sickness and health" in his home until their deaths. He also agreed to arrange for their burials and to have masses said for the repose of their souls. Jean was 77 years old at this time; Catherine was about 70.

Death of Catherine Poitevin

Catherine's story concludes in the shadows of incomplete records. No burial record has been found for her. Given her declining health as described in the 1711 donation—particularly her blindness and severe disability—she likely died within a few years thereafter.

A Family Legacy

Adrien Isabel and Catherine Poitevin represent the determination and resilience that characterized New France's early settlers. Their story—from Adrien's difficult beginnings as an indentured servant to his transformation into a landowner, and Catherine's journey from Paris as a Fille du roi to widowed mother managing colonial life—illustrates the challenges and opportunities that defined the colonial experience. Though Adrien's life was cut short at 38, their union produced four children and established the Isabel/Isabelle family line in Canada. Catherine's subsequent remarriage and her struggle with blindness in old age remind us of the precarious nature of colonial existence, where survival often depended on family networks and community support. Together, they embody the courage required to build new lives in an untamed land, leaving a legacy that would endure for generations.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Journées Européennes du Patrimoine – Visite de l'Église Saint Etienne à Reux," Tourisme Normandie (https://www.normandie-tourisme.fr/agenda/journees-europeennes-du-patrimoine-visite-de-leglise-saint-etienne-a-reux/ : accessed 19 Sep 2025).

Brian M. Nolan, “The Poor Country People of Seventeenth Century France,” We Are Vincentians (https://vincentians.com/en/the-poor-country-people-of-seventeenth-century-france/ : accessed 18 Sep 2025).

"Histoire de Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs," Paroisse Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs (https://asaintnicolas.com/paroisse/saint-nicolas-des-champs/histoire-de-saint-nicolas-des-champs/ : accessed 18 Sep 2025).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/142348 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), marriage of Adrien Isabelle and Catherine Poitevin, 10 Oct 1669, Ste-Famille (Île d'Orléans).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/32915 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), burial of Adrien Isabelle, 7 Jan 1676, Ste-Famille (Île d'Orléans).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/99712 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), marriage of Jean Bourassa and Catherine Poitevin, 4 Nov 1676, Ste-Famille (Île d'Orléans).

"Archives de notaires : Paul Vachon (1655-1693)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4215634?docref=01uRrHMM_5ze6yiNPiVNOQ : accessed 18 Sep 2025), land concession to Adrien Izabel, 22 Jun 1667, images 1078-1079 of 1180.

"Actes de notaire, 1644-1693 // Paul Vachon," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS56-V7BR-1?cat=koha%3A1170052&i=3005&lang=en : accessed 18 Sep 2025), inventory of the community of goods of Catherine Poitevin, widow of Adrien Izabel, 20 Jun 1676, images 3006-3016 of 3433; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Archives de notaires : Gilles Rageot (1666-1691)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4083918?docref=9npNq_8WTO0dHjrGS7D2Hg : accessed 18 Sep 2025), land clearing contract between Etienne Landeron and Adrien Isabel, 30 Oct 1667, image 322 of 1224.

"Archives de notaires : Romain Becquet (1665-1682)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064889?docref=l28YGiW4zeOxEtZSUKBVOw : accessed 18 Sep 2025), marriage contract between Adrien Isabel and Catherine Potevin, 28 Sep 1669, images 976-977 of 1081.

"Archives de notaires : Gilles Rageot (1666-1691)," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4083920?docref=GhEAwWldCDv3x5--4LxOIQ : accessed 18 Sep 2025), marriage contract between Jean Bourassa and Catherine Poittevin, 25 Oct 1676, images 30-31 of 1252.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 18 Sep 2025), " Bail à ferme d'une terre située en l'île St Laurans; par Jean Bourasseau et Catherine Poictevin, son épouse, épouse antérieure de Adrien Isabel, à Jean Jouanne, de l'île St Laurans.," notary P. Duquet de Lachesnaye, 8 Sep 1680.

"Fonds Conseil souverain - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/399532 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), "Arrêt qui ordonne l'emprisonnement d'Adrien Isabel, engagé, sur la demande de son maître, le sieur Charles Aubert de LaChesnaye, qui dit ne pouvoir en avoir service," 7 Jan 1665, reference P1,S28,P281, Id 399532.

“Fonds Cour supérieure. District judiciaire de Québec. Insinuations - Archives nationales à Québec,” digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/81832 : accessed 19 Sep 2025), "Donation d'une terre sise et située en la seigneurie de Lauzon, dépendante de la communauté qui a été entre Jean Bourassa et feue Marie Vallée (Perrette Vallée), par Jean Bourassa, habitant demeurant en la seigneurie de Lauzon, et Catherine Poitevin, sa seconde femme, laquelle est infirme et privée de la vue depuis quelques années; à François Bourassa, leur fils; ladite donation est passée pardevant maître Chambalon, notaire royal en la Prévôté de Québec," 15 Jun 1711, reference CR301,P702, Id 81832.

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 18 Sep 2025), household of Aubert de La Chesnaye, 1666, Québec, page 32 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 19 Sep 2025), household of Jean Bourasseau, 14 Nov 1681, Lauzon, page 218 (of PDF), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/fr/repertoire/isabelle/-isabel : accessed 18 Sep 2025), entry for MICHEL ISABELLE / ISABEL (person #380042), updated on 15 Sep 2016.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/10668 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), dictionary entry for Catherine POTVIN, person 10668.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/2885 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), dictionary entry for Adrien ISABELLE and Catherine POTVIN, union 2885.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/4556 : accessed 18 Sep 2025), dictionary entry for Jean BOURASSA and Catherine POTVIN, union 4556.