Pointe-Gatineau

Dive into the fascinating French-Canadian history of Pointe-Gatineau, Québec, a village shaped by fur traders, lumberjacks and log drivers. Don’t forget to check out the photo gallery!

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Pointe-Gatineau, Québec

1876-1974

Pointe-Gatineau got its name based on geographical location: the village was located south of the confluence of the Gatineau and Outaouais (or Ottawa) rivers. Its early history was shaped by two distinct industries – the fur trade and the lumber industry. Today, Pointe-Gatineau is part of the City of Gatineau, fourth-largest in the province of Québec.

Coureurs des bois and Fur Traders

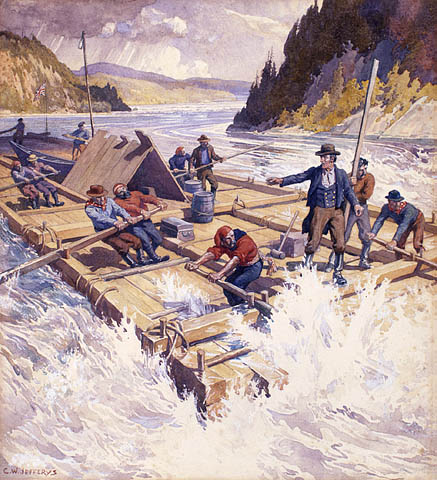

“Voyageurs and Raftsmen on the Ottawa about 1818”, circa 1930 painting by Charles William Jefferys, Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 2955901.

Commercial activity tied to the fur trade took place along the Outaouais river. It acted as a sort of a highway used by native peoples and those of European descent, since it linked the Saint-Lawrence with the west, all the way to the Great Lakes. The Algonquin people became intermediaries in the fur trade, positioning themselves strategically where the Gatineau river meets the Outaouais. They would buy furs from the Huron, who lived near Georgian Bay, and sold them to the French who came from Montreal. In order not to become redundant, the Algonquin strongly discouraged the French from venturing any further west. They maintained this position for several decades, but conflict with between the Iroquois (allied with the English) and the Huron along the Gatineau eventually dispersed the Algonquin further north.

The location of Pointe-Gatineau, however, did not diminish in importance. Historians believe that a fur trading post was erected here in the 17th century, not far from the location of the present-day church, and remained in existence for at least 20 years.

A River of Many Names

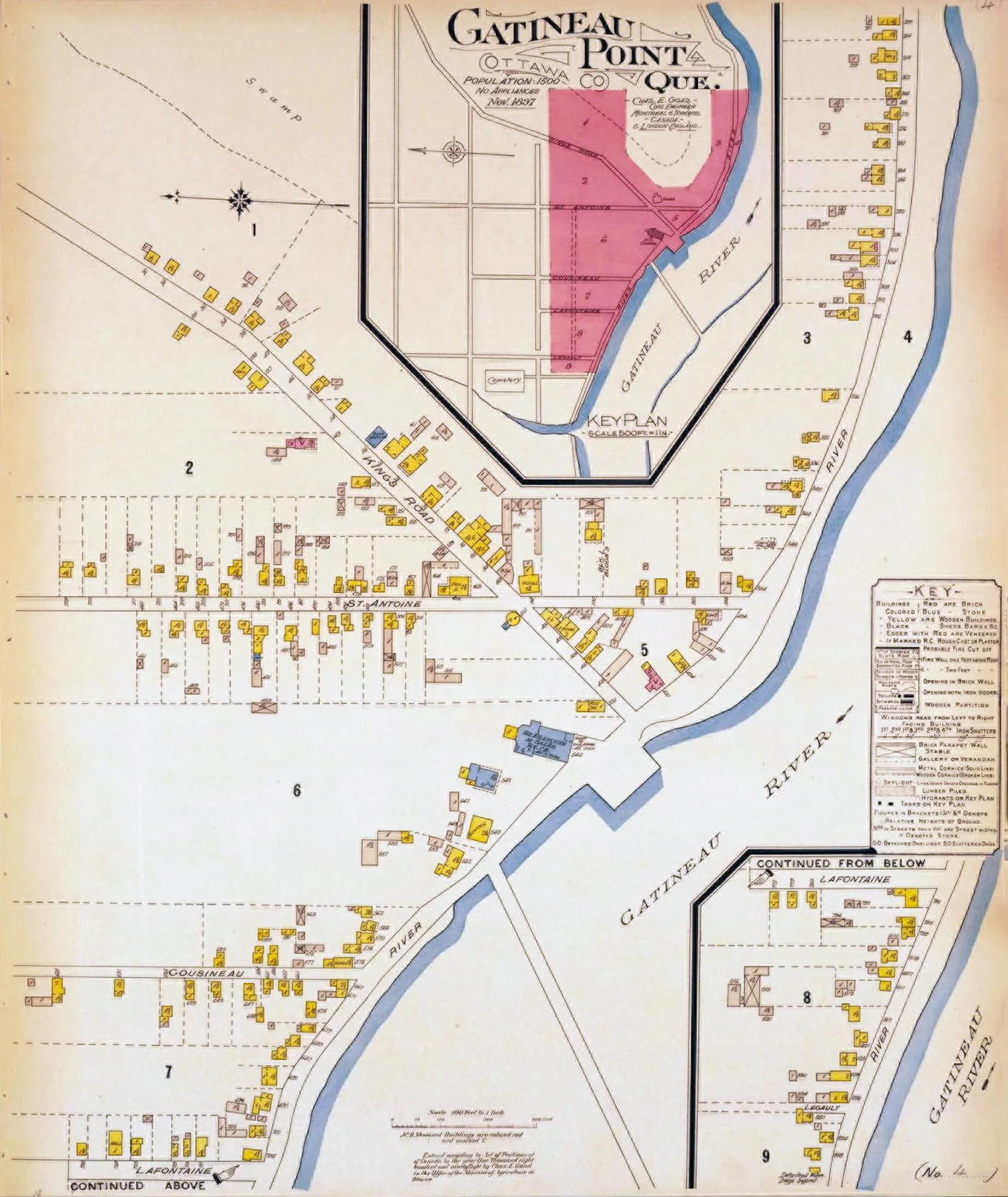

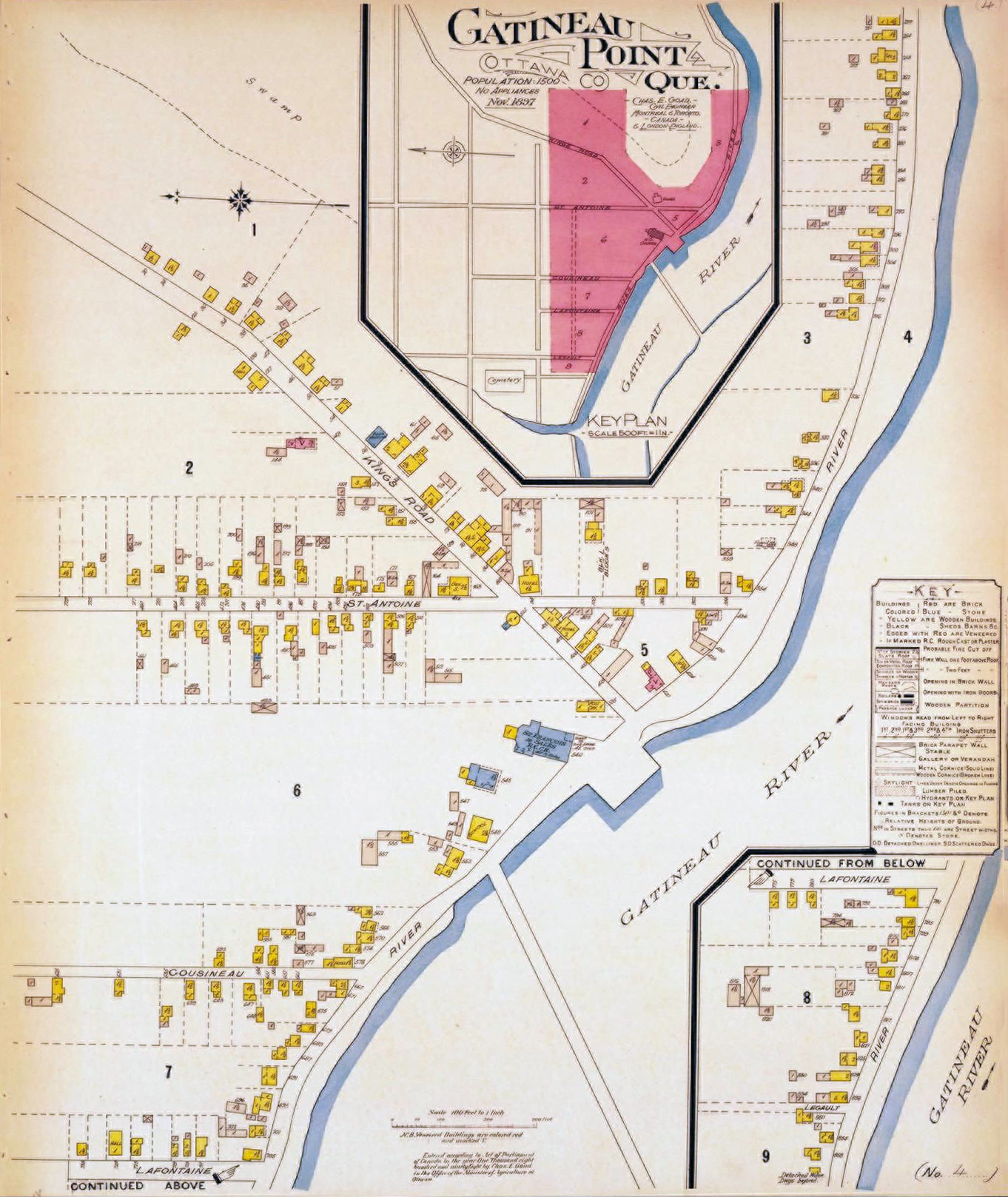

“Gatineau Point, Que.”, 1897 map by Charles Edward Goad, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2246699).

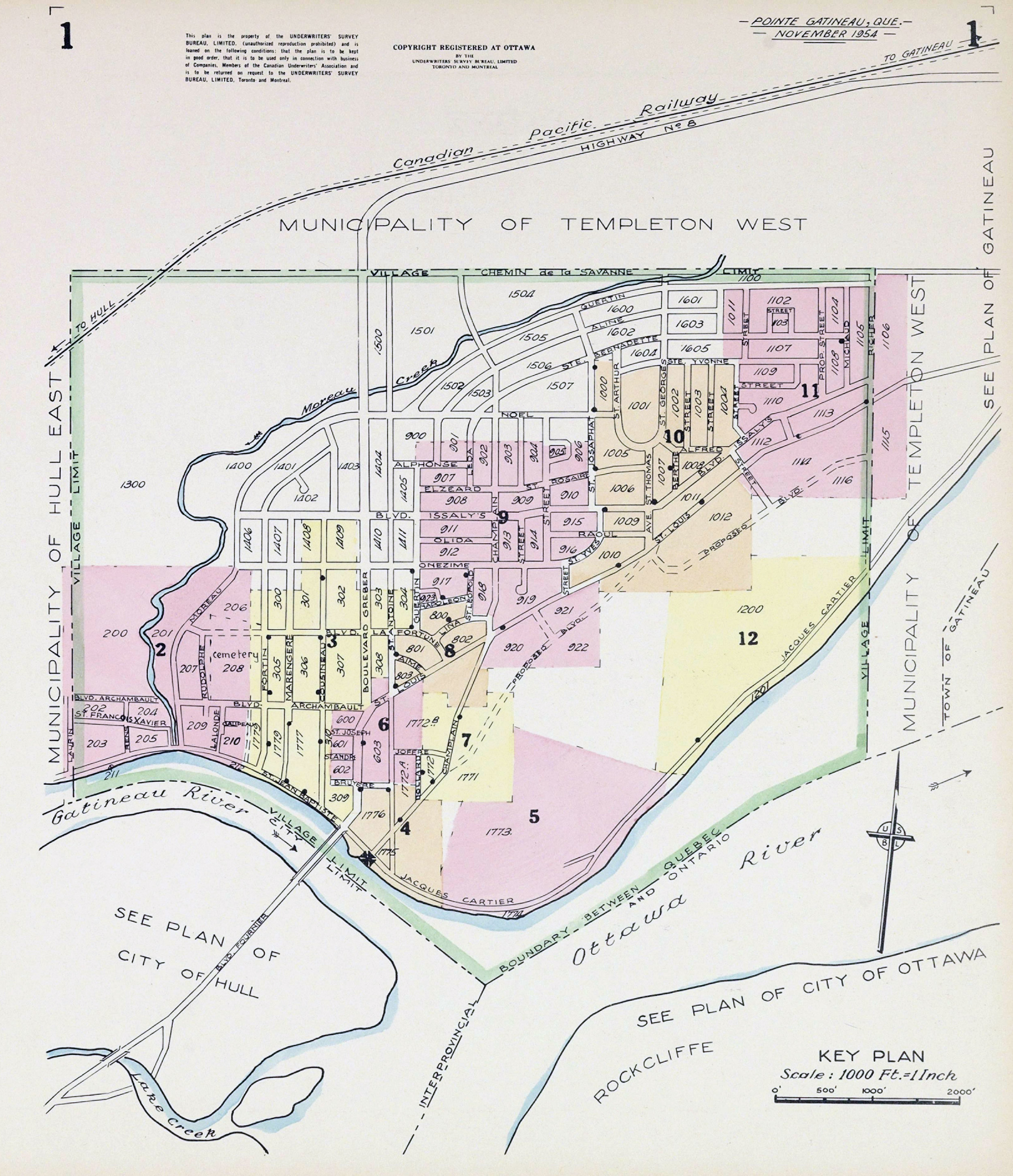

Since its permanent settlement nearly 200 years ago, Pointe-Gatineau has had many names. People in the area first called it the “Long Point de la rivière Gatineau” (the long point of the Gatineau river), which was eventually shortened to “Pointe-de-la-Gatineau” (Point of the Gatineau), then “Pointe-à-Gatineau” (Point at Gatineau), then finally Pointe-Gatineau, the name under which the village was incorporated in 1876. Its anglophone residents, however, generally referred to it as Templeton, which was actually the county in which Pointe-Gatineau was located.

Which leads us to another question. How did the Gatineau river get its name? We unfortunately can’t answer that question with certainty, but historians have offered us several possible explanations. The first possible origin comes to us from the soldier Nicolas Gastineau, whose name appears for the first time in New-France in 1648. Originally from Paris, Gastineau becomes a fur trading clerk for the Compagnie des Cent Associés in Trois-Rivières. We know that the river was part of the fur trading route long used by missionaries and coureurs des bois, but no concrete evidence has been found to suggest that Gastineau himself ever travelled down the Gatineau river. That said, a local legend claims he drowned in the river. Notarial records do confirm Gastineau’s sons were in the Pointe-Gatineau area in the latter part of the 17th century.

Another possibility comes from the indigenous Anishinaabe people of the Ottawa valley, who had multiple names for the river: Tenàgàdino Zìbì, Tenàgàdin Zìbì and Tenakatin Zìbì (various spellings). Zìbì is the Anishinaabemowin word for “river”.

Other possible indigenous origins for the name Gatineau can be found on hand-written maps from a fur trading merchant and a schoolmaster, who called the river Nàgàtinong and d'Àgatinung respectively.

In 1783, a handwritten report sent to the governor of Québec refers to the river as “Lettinoe”. A transcription error, perhaps. It will take several decades before the modern spelling of Gatineau appears on a map. In 1821, a map showing Nepean land concessions was produced, including the “Gatineau River”. To learn more about the origins of the name Gatineau and the validity of each origin story, read this article by Rick Henderson (in French).

Lumberjacks and Log Drivers

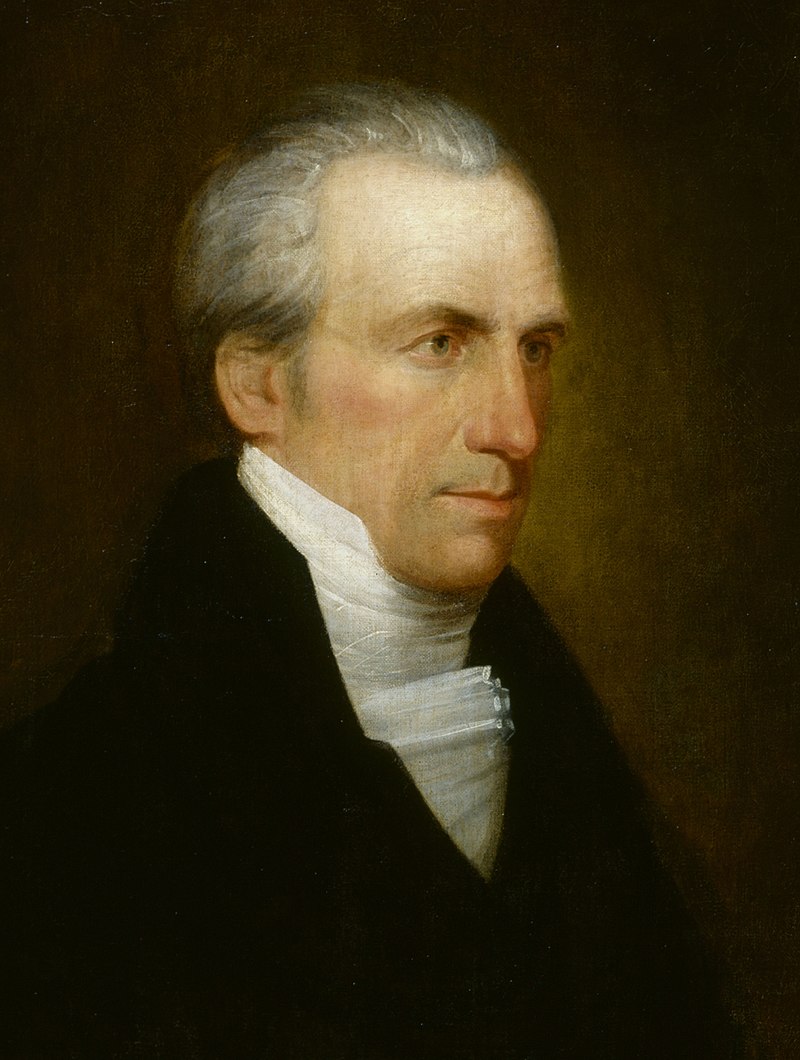

“Portrait de Philemon Wright”, 1810 painting by John James, Wikipedia Commons

In the 18th century, forests in southern portion of Québec along the St-Lawrence were gradually being depleted. Enterprising men began to look westward for new, unsettled territory. One of these men was Philemon Wright. Born in 1760 to Thomas Wright and Elizabeth Chandler in Woburn, Massachusetts, Philemon explored the Ottawa Valley between 1796 and 1799 during multiple voyages. On his last trip back to Woburn, Wright convinced 4 other families and a few dozen men to travel north and settle the area near the current-day Chaudière Falls. Gideon Olmstead, Asa Townsend and London Oxford (the first free black man in the Ottawa-Hull area) were the first owners of property in Waterloo Village, which would come to be called Gatineau Point.

Wright’s settlement became known as Wright’s Town, which eventually became Hull. Soon the town had a lumber mill, a foundry, shops, a bakery, a tannery, a brewery and distillery (fun fact: Wright was one of the first to sell hops to John Molson in Montreal). Numerous farms were also established, including the Columbia Farm located near the Columbia Pond (better known today as Lac Leamy).

During this time, the demand for lumber to build British ships was ever-increasing. Wright saw another opportunity – floating lumber along the Ottawa River all the way to Québec city, a 300-kilometre journey. In July of 1806, the first raft (christened “Columbo”) with 700 oak pieces and 900 planks and beams arrived in Québec, piloted by Wright himself. The timber industry in the Ottawa Valley was born.

Lumberjacks and log drivers moved into the area, including the land that would eventually become Pointe-Gatineau. There, the first lumber workers to cut trees were of Irish origin: Asa Townsend, Gédéon Olmstead, Otes Thomas, Jonathan Simonds and Dudley Moore. However, they appear to have been temporary workers – they didn’t stay put.

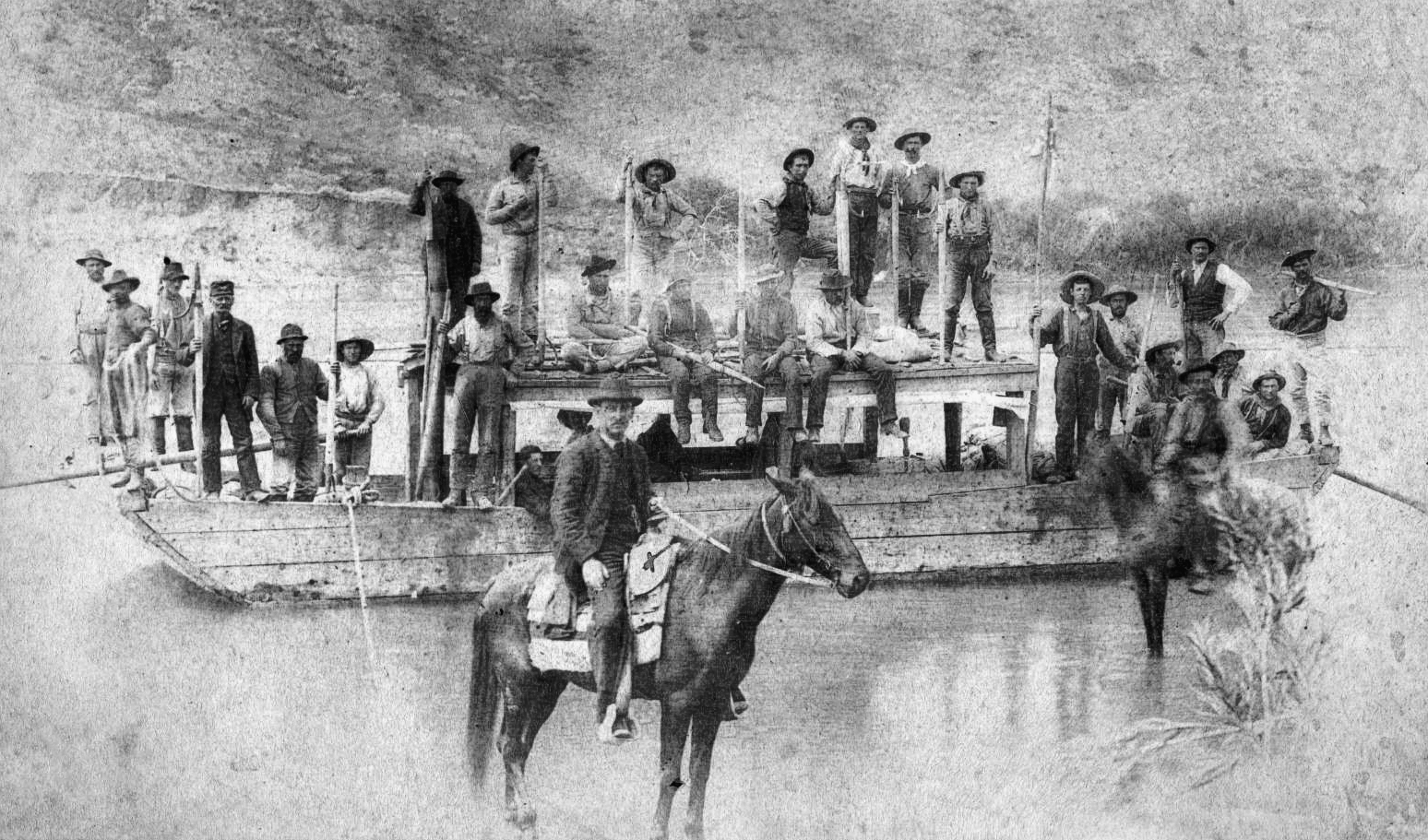

"The first lumber raft down the Ottawa river, 1806", 1806 watercolour by Charles William Jefferys, Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No 2835241.

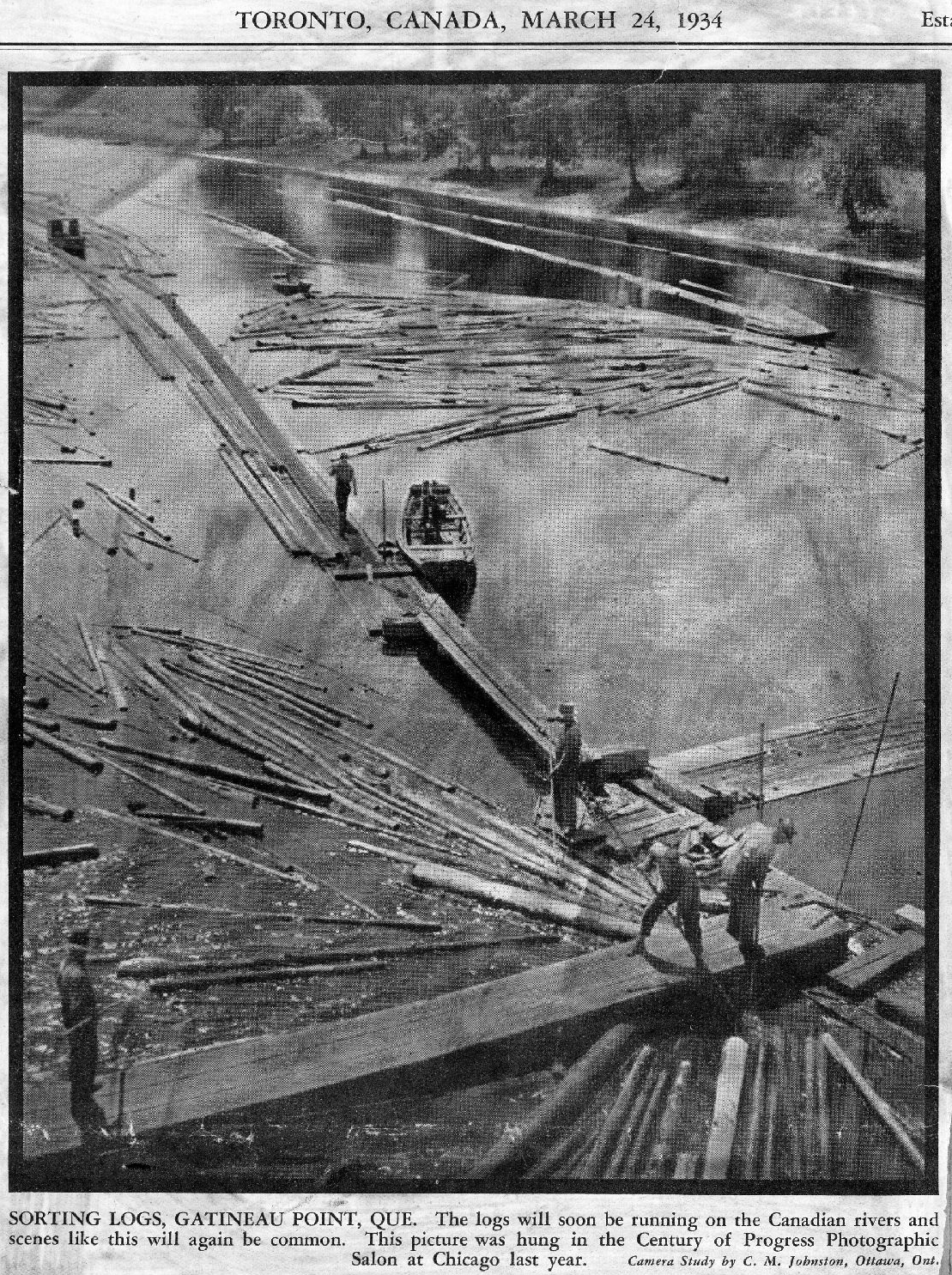

The first man to settle at the “Long Point Range” was Pierre Papin, who established himself there in the spring of 1830, and was followed later that year by more men and their families: the Ouimet, Lorrain, Sanscartier, Lafontaine, Cousineau and others. By 1838, there were a dozen French-Canadian families and one Irish-Canadian family living at Pointe-Gatineau. Trees were chopped down in the wintertime, then squared and floated by log drivers to Québec City in the Spring. Eventually lumber mills were built in Hull and Ottawa, which meant that logs weren’t floated all the way to Québec city. Before long, enterprising men in Pointe-Gatineau decided to build their own mill there. Around 1860, two steam-powered mills existed – one belonging to Pierre Charette and one to the Withcomb and Currier company.

Another somewhat surprising industry sprung up around this time – shoemaking. Log drivers required special footwear and soon there were four successful shoemaking companies set up to meet this need. Also crucial to the economy were the numerous farms in the area, producing several types of grain and fruit.

By the turn of the century, other industries set up shop in the area. Mica Laurentides was established in 1906, Eskimo Lubricating Company in 1938 and Rainbow Plastic Products in 1939. However, by far the most important company to open its doors was the International Paper Company in 1926, located in nearby Templeton-Ouest. This was the catalyst for the creation of the Village of Gatineau in 1933, which had an immensely positive impact on Pointe-Gatineau and its residents.

Bridging the Gap

One problem facing the inhabitants of Pointe-Gatineau was isolation, as the road to Hull was long and arduous. A ferry service was petitioned for and obtained in 1845, linking Pointe-Gatineau to New Edinburgh (not yet part of Ottawa at that time). Once in New Edinburgh, ferry passengers could take a tramway or a horse to Ottawa. By 1868, ferries were steam-powered.

By 1885, talks were under way regarding the construction of a bridge to link Pointe-Gatineau to Rockliffe. However, given the depth of the river and the strength of the currents at this location, it was determined that a bridge here was not feasible. Thus, a bridge was constructed linking Pointe-Gatineau to Hull in 1895. The bridge, later christened Lady-Aberdeen, crossed the Gatineau river near the St-François-de-Sales church. Due to political squabbling between municipalities over who should cover expenses, the bridge often became unusable and too dangerous to cross because of damage and other wear-and-tear. This situation culminated in an incident where International Paper employees, trying to get to work, broke the chains from the bridge in an attempt to cross. Authorities realized the importance of having a reliable bridge for Pointe-Gatineau residents and a new bridge was constructed in 1932.

“Pont de la Pointe Gatineau sur la rivière Gatineau à Pointe-Gatineau”, 1946 photo by Olivier Desjardins, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3026950).

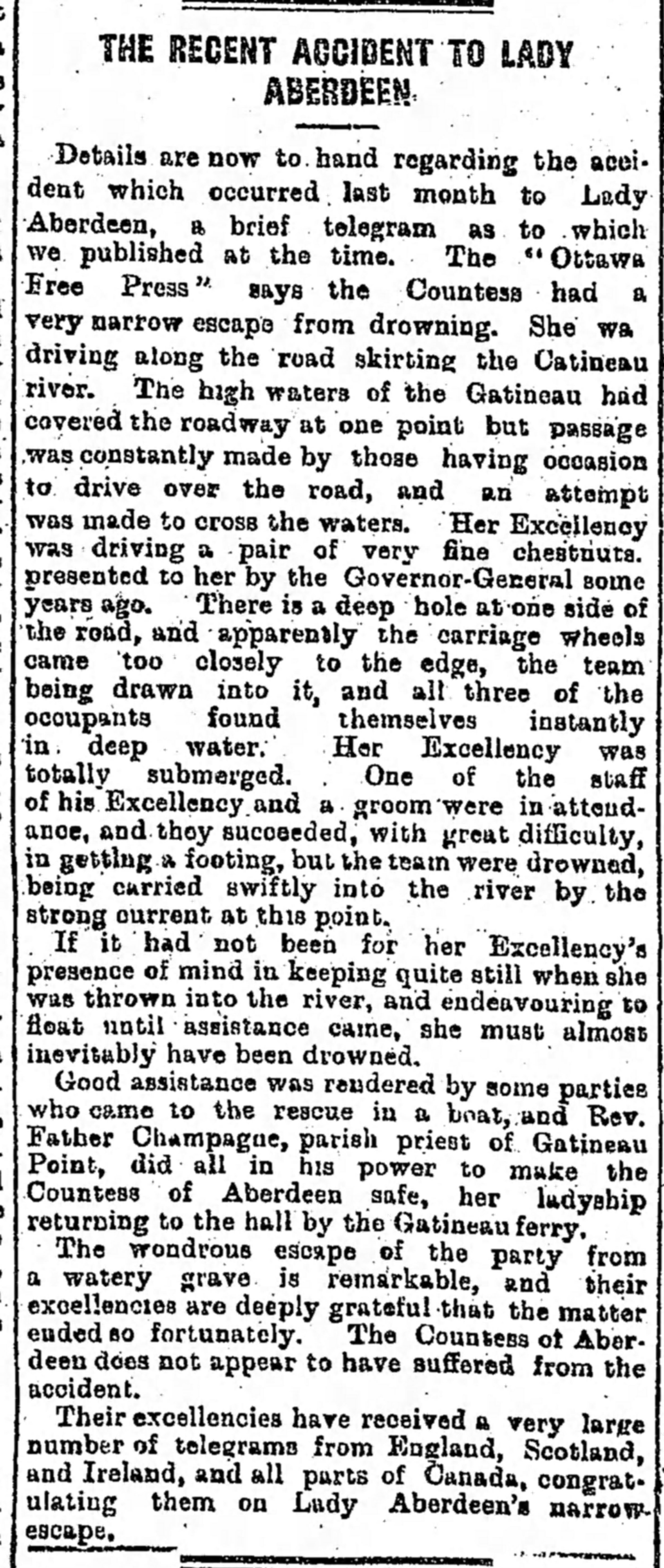

Rescuing Lady Aberdeen

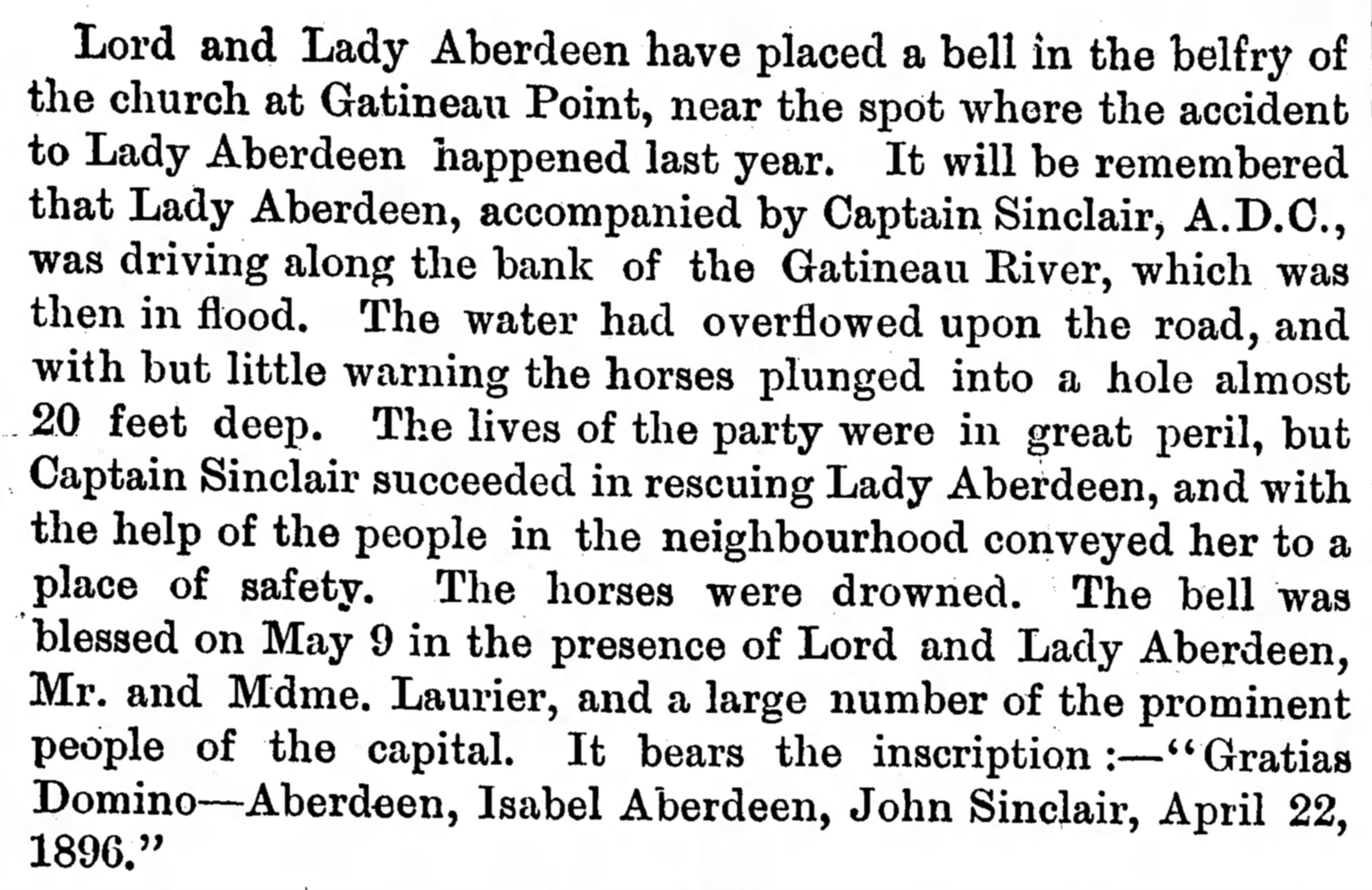

Lady Aberdeen, born Ishbel Marie Marjoribanks, and married to the Earl of Aberdeen, John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, had developed a friendship with the priest at St-François-de-Sales in Pointe-Gatineau, Isidore Champagne. She travelled there often to visit him – both shared an interest in music and Champagne was known to be a very talented musician. On one faithful day in 1896, Lady Aberdeen was returning from a visit to Champagne aboard her horse-drawn vehicle, when her horses, frightened by rising river waters, plunged headfirst into a hole nearly 20 feet deep, taking the countess, the carriage, the coachman and the captain with them. Nearby residents of Pointe-Gatineau Charles Carrière, Bénoni Tremblay et Félix Bigras witnessed the accident and jumped in to save the three victims.

To express her gratitude to the men who came to her rescue and the village of Pointe-Gatineau, Lady Aberdeen gifted the St-François-de-Sales parish with a new church bell in 1896 weighing 1,464 pounds.

Above: “Archie Gordon, his cousin Cosmo Gordon, and Lady Aberdeen”, 1894 photo by William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No 3422863.

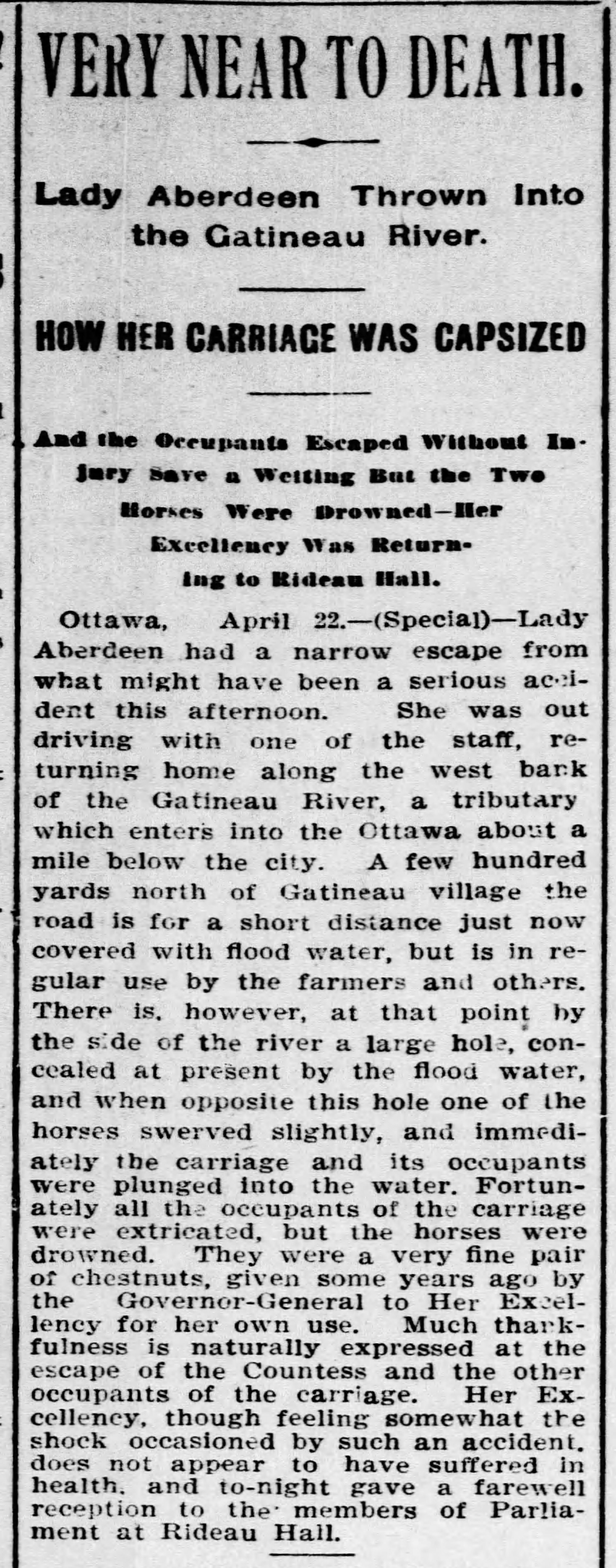

Right: 23 Apr 1896 article appearing in the Windsor Star

Natural Disasters

“Pointe-Gatineau”, 1947 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique.

Before the construction of locks on the Outaouais river at Témiscamingue in 1911 and the hydroelectric power station at Hull in 1920, flooding was an annual event that Pointe-Gatineau residents dreaded. Every spring, as water descended from the north after the snow melt, waters in the Gatineau river would rise substantially. The worst flooding to hit the city occurred in 1876. That year, only the portion of land containing the church, the presbytery and some 15 houses were untouched by flood waters. About 200 houses had to be abandoned. Some 30 houses were completely swept away, as well as the city’s wooden sidewalks and small bridges. The hydroelectric dam built at Carillon in 1964 also helped to alleviate the flooding.

Worship & Education: the Parish of St-François-de-Sales

The first church in Pointe-Gatineau was constructed in 1836, at the corner of Saint-Antoine and Champlain. At this time the village did not have its own resident priest and the church building was quite modest in size. Four years later, a slightly larger wooden church was erected on the site of the present-day church and blessed by Montreal Archbishop Ignace Bourget.

In 1848, there were 140 Catholic families living at Pointe-Gatineau and 50 Protestant families. Within 20 years, there were over 400 families in the parish. Given the upward trajectory of the population, a new stone church was built in 1886 and still stands today. The first resident priest of St-François-de-Sales was French Archbishop Joseph-Gaspard-Suzanne Guinget.

Around the same time as the first church was built, the first primary school in the county of Templeton also opened in 1839. Two thirds of the school books were in English, catering to the mostly Irish population living in the area. Around 1848, a Catholic boys’ high school was also opened. 1872 saw the arrival of the Soeurs Grises-de-la-Croix (the Grey Nuns), today the Congrégation des soeurs de la Charité d'Ottawa (the Sisters of Charity of Ottawa), to teach boys and girls. Between 1875 and 1879, there were 4 or 5 nun teachers. In 1885, a new school building was erected, which would become the Saint-François-de-Sales convent a year later. By 1897, only girls were accepted at the school. In 1905, a new school called Saint-Antoine was opened for boys by the Frères de l’Instruction chrétienne (Brothers of Christian Instruction). Up until 1961, these two religious orders were responsible for the education of children in Pointe-Gatineau.

1952 wedding of my grandparents, Raymond Berlinguette & Gisèle Charron at St-François-de-Sales, 1952 photo scanned and restored by author Kim Kujawski. Also pictured are Irène Lalande and Wilfrid Berlinguette (to the left of the groom) and Philorum Charron and Mélina Millaire, to the right of the bride.

Pointe-Gatineau officially became a city on 10 June 1959. In 1975, with a population of 15,608, it was amalgamated into the City of Gatineau. In 2002, the cities of Gatineau, Hull, Buckingham, Aylmer and Masson-Angers were merged to become the new City of Gatineau.

Photo & Image Gallery

![Postcard of Pointe-Gatineau, 190[?]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bb6661d8dfc8c1836526d3a/1554314383812-NHGTIWHS39FVK7RPV47O/1900c+Gatineau+Point+Ottawa.jpg)

Want to start researching your own family roots? Contact us today!

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you!

Sources:

Anna Desmarais, “The Capital Builders: Lady Aberdeen, a feminist for Canada”, 26 Jun 2017, The Ottawa Citizen (https://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/the-capital-builders-lady-aberdeen-canadian-feminist)

Rick Henderson, “« Gatineau » : Pagayer à travers la toponymie d'une rivière”, 20 Jun 2020, Capital Chronicles (https://www.capitalchronicles.ca/post/gatineau-pagayer-%C3%A0-travers-la-toponymie-d-une-rivi%C3%A8re). Originally published in Up the Gatineau!, Société historique de la vallée de la Gatineau, vol. 46.

Vito Pilieci, “The Capital Builders: The founding of the Ottawa we know today was largely thanks to an American”, updated 18 Jul 2017, The Ottawa Citizen (https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/the-founding-of-the-ottawa-we-know-today-was-largely-an-american-family-affair)

“Ville de Pointe-Gatineau (1876-1974) – Historique”, Ville de Gatineau (https://www.gatineau.ca/docs/guichet_municipal/archives/docs/pg_hist.htm)

“Ville de Gatineau”, Histoire du Québec (http://histoire-du-quebec.ca/gatineau)

Photo Credits:

"The first lumber raft down the Ottawa river, 1806", 1806 watercolour by Charles William Jefferys, Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No 2835241 (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayItem&rec_nbr=2835241&lang=eng&rec_nbr_list=2835241,2897203).

“Portrait de Philemon Wright”, 1810 painting by John James, Wikipedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philemon_Wright_color.jpg).

“Voyageurs and Raftsmen on the Ottawa about 1818”, circa 1930 painting by Charles William Jefferys, Library and Archives Canada (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2019-04-01T23%3A11%3A49Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=2955901&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng), MIKAN 2955901. Description: “Philemon Wright's first timber raft went down the Ottawa River from Hull to Montreal in 1806. There is a drawing by Jefferys of this event, published in "The Picture Gallery of Canadian History", entitled: "The First Raft on the Ottawa, 1806." The date appearing in the title has historically been part of the title given to the painting. The two paintings in this collection (1973-16-1 and 1973-16-2) were murals in the Chateau Laurier in Ottawa, part of a series of four images depicting important events in the history of the Ottawa River.”

“Travailleurs forestiers (draveurs) sur un bac et homme à cheval sur les rives de la rivière Outaouais”, circa 1890 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3263208).

“L. to R.: Archie Gordon, his cousin Cosmo Gordon, and Lady Aberdeen”, 1894 photo by William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No 3422863 (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayItem&rec_nbr=2835241&lang=eng&rec_nbr_list=2835241,2897203).

“Gatineau Point, Que.”, 1897 map by Charles Edward Goad, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2246699).

“Gatineau Point, Ottawa”, 190[?] postcard (unknown artist), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2247500).

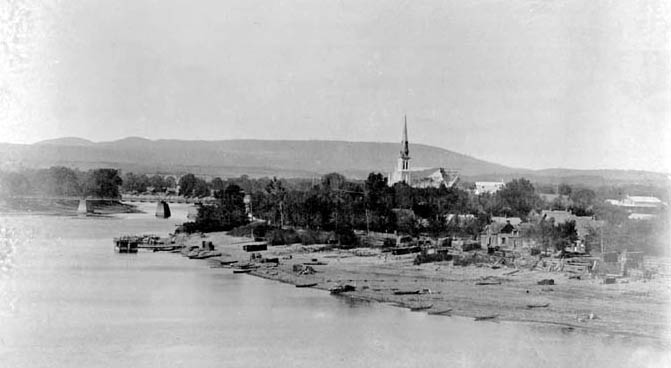

“Gatineau Point”, 1902 photo by James Ballantyne, Library and Archives Canada (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2019-04-01T23%3A25%3A54Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=3265309&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng), MIKAN 3265309.

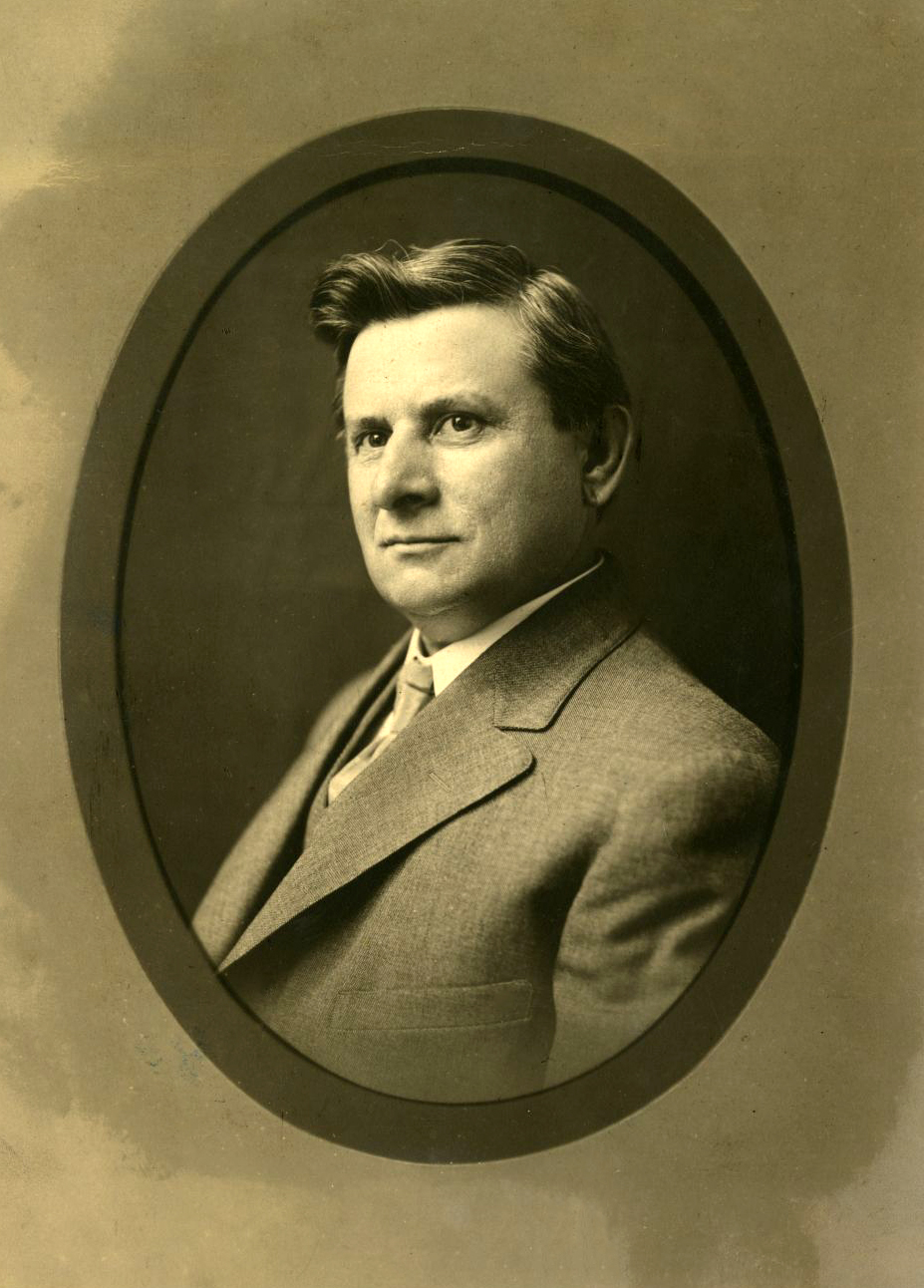

“L. N. Villeneuve, de Pointe-Gatineau” , circa 1904 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3026950).

“Collège Saint-Alexandre de Pointe-Gatineau”, 1920 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3074005).

“Sorting timber, Gatineau Point, P.Q.”, 1934 photo by Clifford M. Johnston, Library and Archives Canada (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2019-04-01T23%3A22%3A44Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=3372639&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng), MIKAN 3372639

“Timber boom, Gatineau Point, P.Q.”, 1935 photo by Clifford M. Johnston, Library and Archives Canada (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2019-04-01T23%3A23%3A48Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=3372643&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng), MIKAN 3372643

“Coupure de presse - Sorting logs, Gatineau Point, Quebec”, 1934 newspaper article (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3333236. Description: “The logs will soon be running on the Canadian rivers and scenes like this will again be common. This picture was hung in the Century of Progress Photographic Salon at Chicago last year.”

“Rivière Gatineau: érosion à Pointe-Gatineau”, 1938 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3328798).

“Pointe à Gatineau, comté de Hull”, 1941 photo by Herménégilde Lavoie, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3021401).

“Poste de pompiers à Pointe-Gatineau, Hull”, 1944 photo by Ernest Lavigne, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3013595).

“Pont de la Pointe Gatineau sur la rivière Gatineau à Pointe-Gatineau”, 1946 photo by Olivier Desjardins, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3026950).

“Pointe-Gatineau”, 1947 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3331763?docref=RtvtKTNeZ2VTxnqlSIJtUg).

“Pointe-Gatineau”, 1947 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3331763?docref=TUQ0733mvg-KZHWIyeDM6w).

“Pointe-Gatineau”, 1947 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3331762).

“Pointe-Gatineau”, 1947 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3331762?docref=akNuGbwsJwqKEYCMDa0-vA).

“Familles délogées à Pointe-Gatineau”, 1947 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3331767?docref=WfTKu0GQZgCWmPPVc7U56A).

“Pont Moreau sur la rivière Moreau à Pointe Gatineau. Comté de Hull”, 1950 photo by C.-R. Yespelkis, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3052748).

Wedding of my grandparents, Raymond Berlinguette & Gisèle Charron at St-François-de-Sales, 1952 photo scanned and restored by author Kim Kujawski.

“École, Pointe-Gatineau, comté de Gatineau”, 1952 photo by Delvica Allard, Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3472295).

“Insurance plan of the village of Pointe Gatineau, Que. [document cartographique] Underwriters' Survey Bureau, Limited”, 1954 insurance plan created by the Underwriters’ Survey Bureau (Toronto), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2244125).

“Équipe de ballon-balais de Pointe-Gatineau”, 1962 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3126143).

“Promesse des Guides : Presbytère St-Francois de Sales, Pointe-Gatineau”, 1962 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3125424).

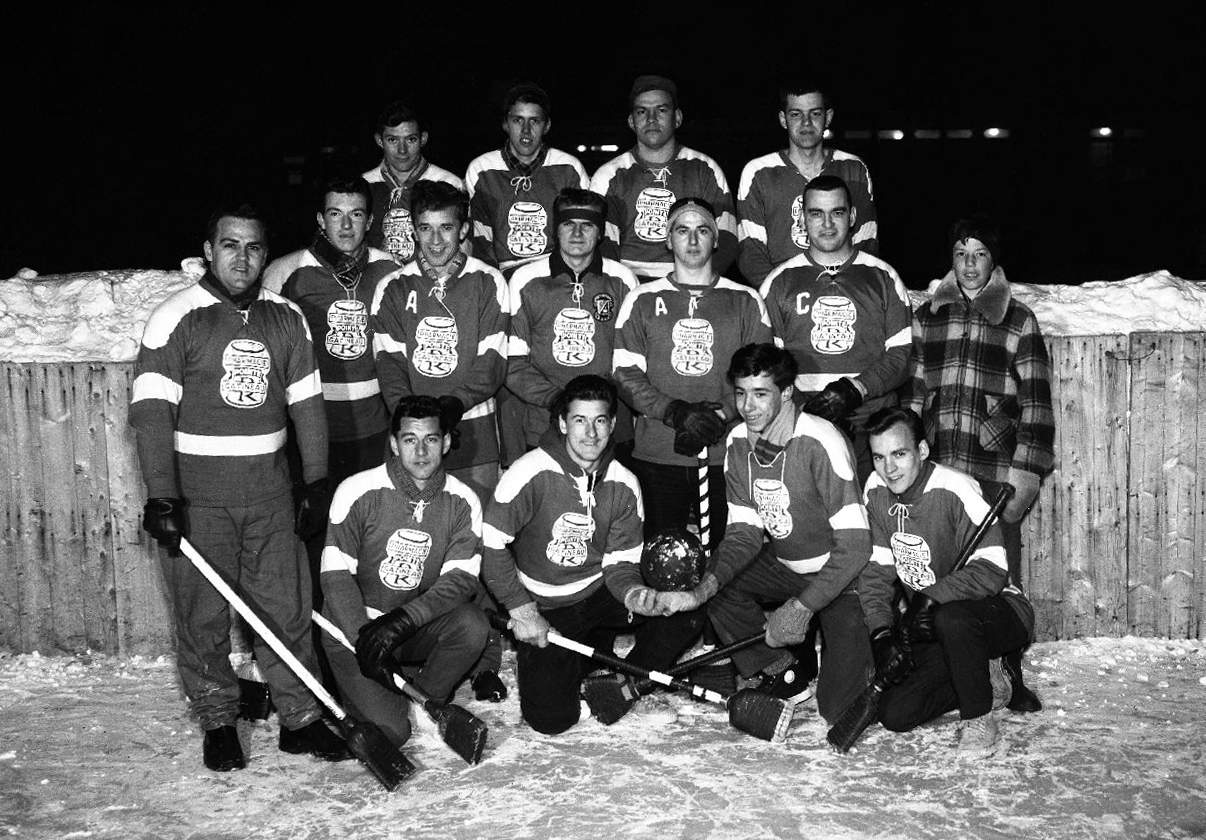

“Équipe de hockey Saint-Rosaire de Pointe-Gatineau”, 1963 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3126043).

“Carnaval de la paroisse Saint-Rosaire de Pointe-Gatineau”, 1963 photo (unknown photographer), Bibliothèque et archives nationales, BAnQ numérique (http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3125845?docref=IZM7847MMJkWJii0jnrU3g).

“Ottawa River and Gatineau Point, P.Q. from Government House Gate, Ottawa, Ont.”, undated photo (unknown photographer), Library and Archives Canada (http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/ourl/res.php?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&url_tim=2019-04-01T23%3A17%3A56Z&url_ctx_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=3372622&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fcollectionscanada.gc.ca%3Apam&lang=eng), MIKAN 3372622.