A French-Canadian Easter

Today's Easter celebrations tend to focus on modern traditions rather than religious ceremony. Think Easter egg hunts, chocolate bunnies, glazed ham and family dinners. Did any of these traditions exist 100 or 200 years ago? What was Easter like for our ancestors centuries ago?

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

A French-Canadian Easter

Similar to Christmas, today's Easter celebrations tend to focus on modern traditions rather than religious ceremony. Think Easter egg hunts, chocolate bunnies, glazed ham and family dinners. Did any of these traditions exist 100 or 200 years ago? What was Easter like for our ancestors centuries ago?

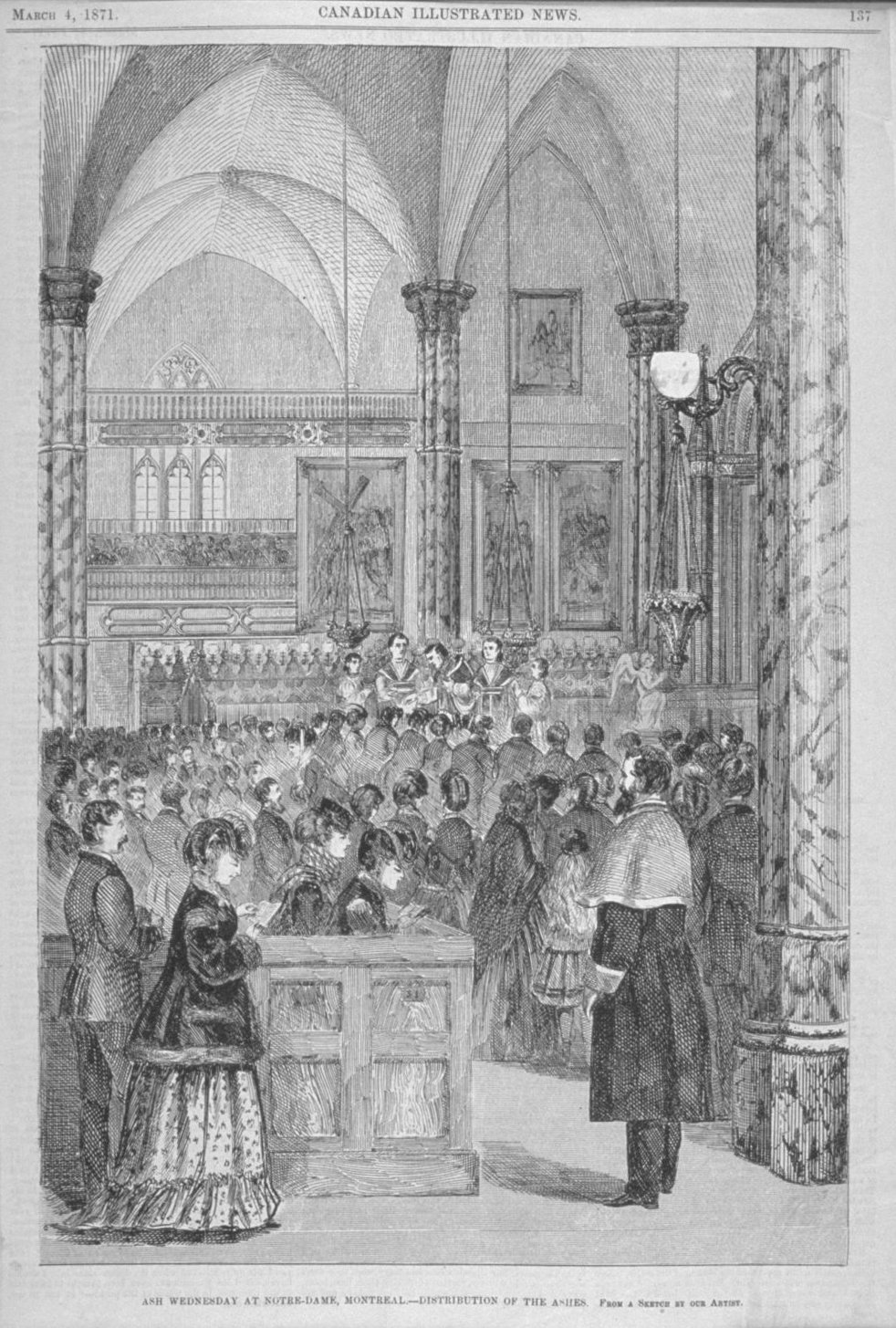

“Ash Wednesday at Notre-Dame, Montreal," illustration in Canadian Illustrated News, 4 Mar 1871, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

For our ancestors, Easter was a religious holiday. For Christians, Easter is only part of a celebration that begins with Lent ("Carême" in French) on Ash Wednesday and ends on Easter Sunday. In certain parts of French-speaking Canada, lent was interrupted midway by "Mi-Carême,” or mid-Lent, which has its origins in France. Each of these events had their own traditions.

Lent

Beginning on Ash Wednesday, Lent was a solemn 40-day period of fasting, abstinence, prayer and penitence. Fasting meant eating the equivalent of a single meal during the day, with a frugal diet in the morning and evening, and no snacking between meals. The most pious would weigh their food. Children were exempt from fasting, as were the sick and the elderly.

Abstinence meant that meat was strictly forbidden. The devoutly religious would deprive themselves of other vices as well: they would refrain from smoking, consuming sugar (even in coffee) and swearing. Some children were prohibited from eating any sweets or candy.

The local priest has arrived unannounced at a parishioner's home only to catch the family in the forbidden act of eating meat during Lent. Captured in “Breaking Lent (or A Friday's Surprise)”, circa 1847 painting by Cornelius Krieghoff, Art Gallery of Ontario.

Transgressions were taken very seriously. On October 26, 1670, a man named Louis Gaboury was condemned for having eaten meat during Lent without the permission of the church. "He was condemned to pay for a cow and a year's profit of it, in addition, to be tied to the public post for three hours' time, and then to be led to the front door of the chapel of l'île d'Orléans where, kneeling, hands clasped, head bare, he will ask God, the king and the justice for forgiveness."

Mid-Lent

Dating back to the Middle Ages, Mi-Carême celebrations took place in the middle of Lent, on the Thursday of the third week. Depending on time and place, mid-Lent could last from one day up until one week. The festivities were a way of breaking the fast of Lent and having some fun with friends and neighbours. It was very popular in the 19th century, then slowly declined after the First World War. Celebrations normally involved donning masks and costumes, and going from house to house to entertain residents. They would sing and dance, while people around them tried to guess their identities. Once masks were removed, the visitors typically had a bite to eat and something to drink before moving onto the next house. [Newfoundland readers will find this tradition very similar to mummering. Mid-Lent festivities were also comparable to those of Mardi Gras.]

“La mi-carême au ‘Montagnard’ “ (Mid-Lent at the "Montagnard" hockey club) by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte. Published in Le Monde illustré, Vol. 17, no 882 (30 Mar 1901), p. 802. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Mid-Lent, an example of a cultural transfer from Europe to America, is a celebration that uses the power of the mask in a collective ritual of derision. During this celebration, the mask protects, liberates, guarantees anonymity, transforms, frightens and allows confusion.”

Mi-Carême "runners" in Chéticamp, mid-1930s. Mi-Carême Interpretive Centre.

Mi-Carême is still celebrated today in some Québec villages: L’Isle-aux-Grues, Natashquan and Fatima (Îles-de-la-Madeleine). It is also celebrated in the Acadian villages of Saint-Joseph-du-Moine, Magré and Chéticamp.

“A group of residents of Saint-Louis de Gonzague dressed up for Mi-Carême,” 1937 photo by Sister Marie-de-l'Eucharistie (Elmina Lefebvre), Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Watch this video to see how Mi-Carême is celebrated in Chéticamp (in French with English subtitles).

Holy Week

Palm Sunday ("Dimanche des Rameaux," or "Pâques Fleuries"), the day when Jesus entered Jerusalem, marks the beginning of Holy Week. Parishioners were expected to go to church for confession and take communion. For our French-Canadian ancestors, this had to be done by Quasimodo, the Sunday following Easter Sunday. It was important not to wait until the very last minute to do so, lest they would be accused of carrying out "Pâques de renard" (a fox's Easter). This is a Québec expression which translates to fulfilling Easter duties like a fox. In other words, to be cunning or be fearful as a fox.

During Palm Sunday mass, the priest would bless the "palms" brought to the church by parishioners. Since palms weren't readily available in Canada, people from the countryside normally brought fir or spruce branches, from which cones were removed and tied together with a ribbon, along with paper flowers. In bigger villages and in town, these branches were purchased and then divided into smaller bunches and put in every room in the home. They replaced the ones put there a year prior, which would now be burned. They were affixed to crucifixes or placed above doorways. These branches or "palms," a symbol of the protection of God, were meant to bring good luck to the family, protect them from bad weather, fire and disease, as well as bless the deceased.

Holy week revolved around fasting, praying and attending services, even more so than during Lent, and especially during holy days. Holy Thursday mass was a grandiose event, with organ music, the procession to the altar, singing and bell-ringing. Church bells were quiet from Holy Thursday to Holy Saturday, respecting the last moments of Christ, before returning triumphantly on Sunday to celebrate his resurrection. On Thursday night, family members would take turns to pray the Blessed Sacrament.

The altar observed during a religious ceremony held on Holy Thursday by the Fathers of the Most Blessed Sacrament. The priests and the faithful are gathered for prayer. Photo by Claude Décarie, April 1947. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

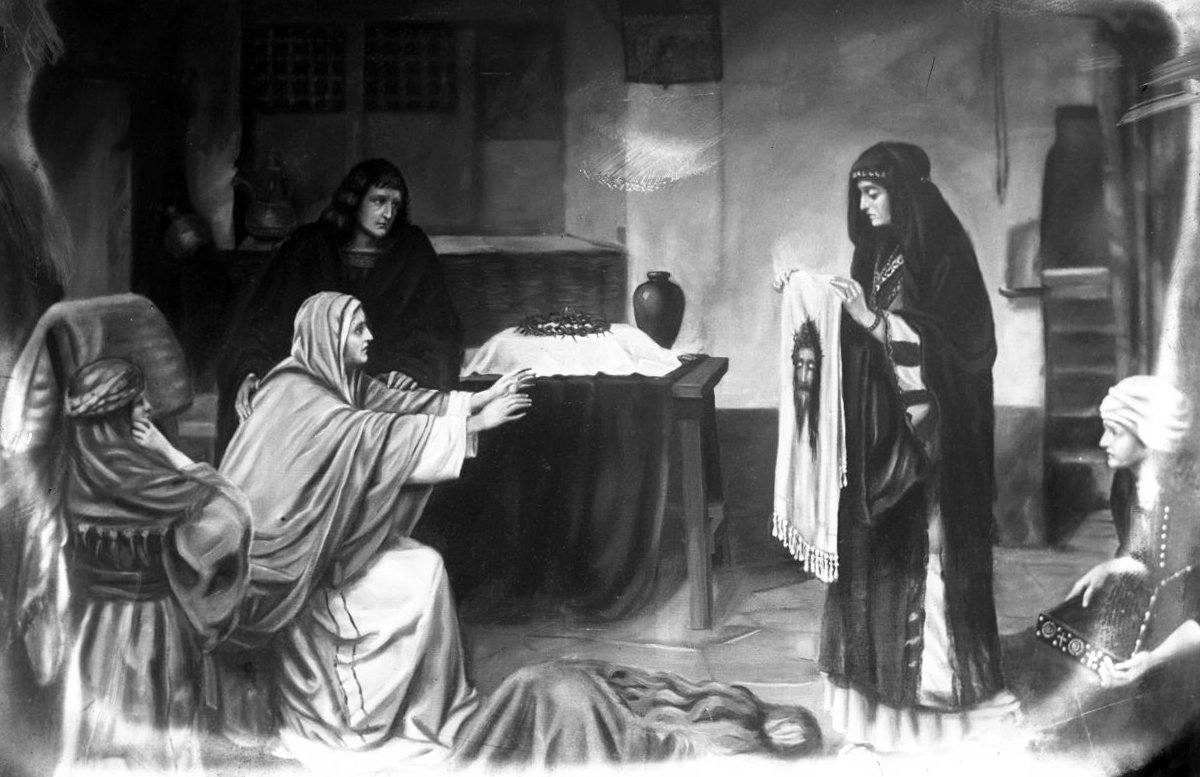

Good Friday, on the other hand, was a sombre affair. It was a day of mourning, recalling the death of Christ. One was not supposed to work except to accomplish the bare essentials and most shops would be closed until mass was over. Morning mass on Good Friday was a long ceremony. The priest would recite the Passion of the Christ. The faithful would also walk the Way of the Cross (or “Stations of the Cross”), commemorating the path taken by Jesus, wearing the cross, to Mount Calvary on the way to his crucifixion. This was normally a path set up with 14 stations in the church nave, each with an image or painting, where a prayer would be recited. At three o'clock, the moment of Christ's death, those who could not make it to the church for the Stations of the Cross prayed silently at home or recited their rosary.

Several superstitions were specific to Good Friday, to reinforce fasting and penitence:

Anyone undertaking work of any kind on Friday will have bad luck.

Metal must not penetrate soil on Good Friday, so clearing land, farming, etc. should be avoided.

Looking at oneself in a mirror will bring bad luck.

Clothing washed on Good Friday will never truly be clean.

Maple trees must never be tapped, as blood will flow instead of sap.

Some superstitions brought good luck:

Bread and pastries baked on Good Friday will not mould and will heal mild illnesses like colds and whooping cough.

A baby weaned on Good Friday will grow healthy and have a prosperous life.

A boy wearing long pants on Good Friday will have a happy household.

Holy Saturday was generally a quiet day. The church was cleaned, and the tabernacle emptied. In the evening, however, the Easter vigil took place. It was the biggest celebration of the year, in honour of Christ's resurrection. The priest would bless the new fire and the water that would baptize newborns. Sometimes a baptism was celebrated. The end of Holy Saturday officially marked the end of Lent.

Painting representing Holy Saturday, by Sister Marie-de-l'Eucharistie (Elmina Lefebvre), 1912. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Easter Water & Holy Sunday

Another tradition still practised in some parts of Québec, is the collection of "Easter water" at dawn on Easter Sunday morning, before sunrise. This water needed to be taken from a stream or small river. It was said to have magical properties; palms blessed with the water would be used to bless one's home. Similar to holy water, Easter water was also thought to heal the sick and protect the home and family from bad weather. It was also thought to ward off evil spirits. The tradition can be traced back to New France and is still practised today in some smaller villages.

Easter at Boucherie Fortunat Octeau, Chicoutimi, around 1920. “Joseph-Fortunat Octeau prepares traditional Easter ham for his customers. His shop on rue Racine, like most shop windows of the time, is adorned with paper flowers, a traditional decoration for Easter week.” Wikimedia Commons.

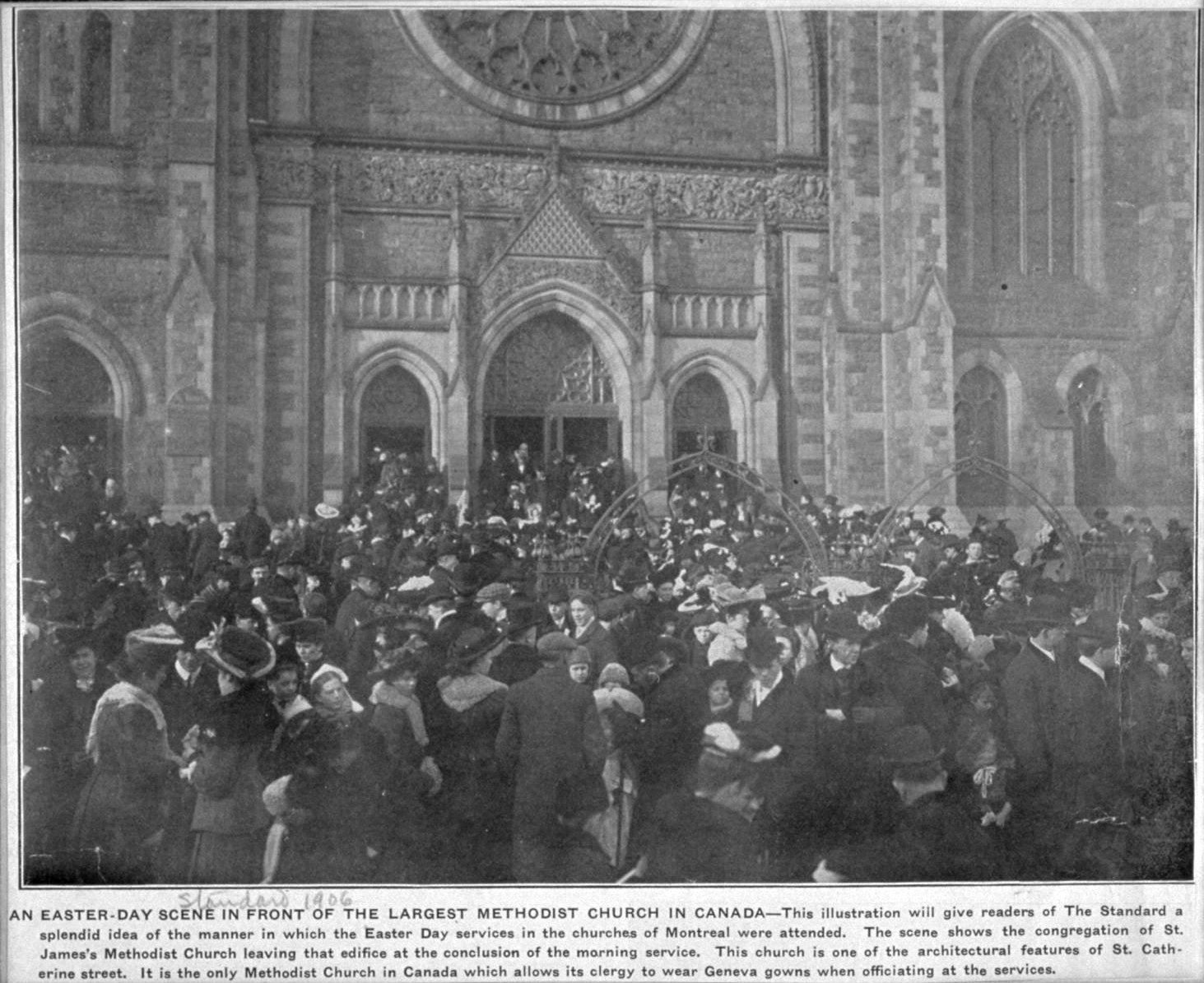

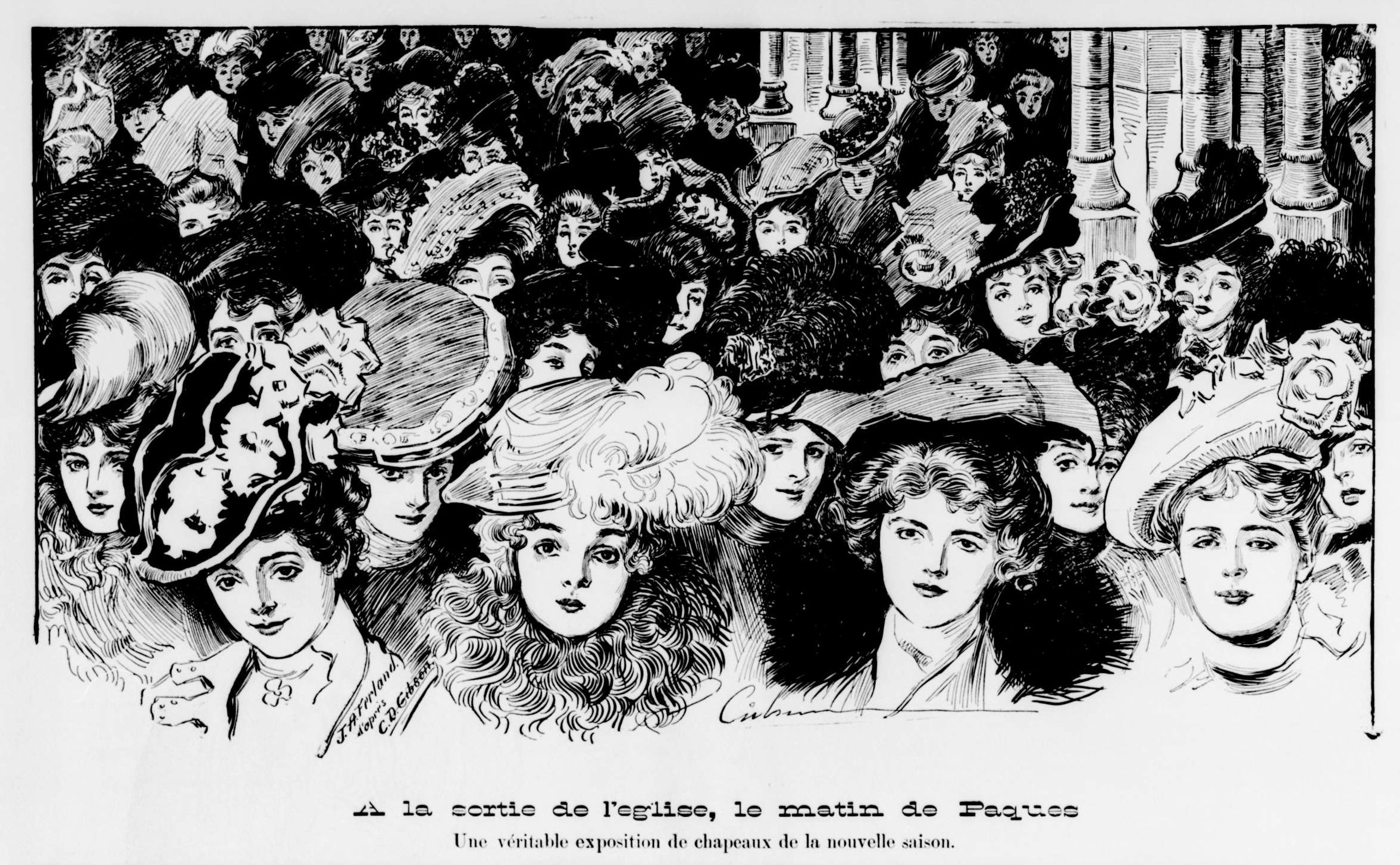

Many markets reopened on Easter Sunday, marking the beginning of spring. Shops, stalls and even horses would be decorated with paper flowers. Many of our so-called modern traditions may have pagan roots, relating to springtime and renewal (eggs, flowers, chicks, rabbits). In this spirit of "renewal," many also donned new clothing and, especially for women, new hats. And finally, on Sunday evening, the resurrection of Christ was celebrated with a family dinner. After a long period of fasting, this meal would be particularly bountiful. In French-speaking Canada, pork was the meat of choice: from smoked bacon roasted in a pan centuries ago, to today's pre-cooked ham prepared in an oven. When eaten in the spring, ham was said to bring good luck. In anglophone households, lamb was the meat of choice, as Jesus was called the "Lamb of God."

Easter day crowd in front of St. James Methodist Church, St. Catherine Street, 1906. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Modern Traditions & Symbols

"Mademoiselle Gravel", a young orphan with an Easter basket as an accessory. 1917 photo by Sister Marie-de-l'Eucharistie (Elmina Lefebvre). Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

In more contemporary times, ham is still eaten in French-Canadian households, normally spiced with cloves, with maple syrup (or cider) and pineapple (certainly not something they had in New France!) More closely associated with British tradition, hot cross buns are normally eaten on Easter Friday. Easter also means chocolate and Easter eggs. Most families participate in an Easter egg hunt, with actual eggs soon replaced with those of the candy or chocolate variety.

The Easter Bunny is said to have been introduced to the United States by German immigrants in the 1700s, who spoke of a magical rabbit able to lay eggs. The children of the German immigrants in Pennsylvania would prepare nests for the Easter bunnies to lay their eggs in on Easter Sunday morning. Coloured eggs eventually morphed into sweets and chocolates, and the tradition soon spread across the country, and across the border into Canada. The exact origins of this legend are unclear, but rabbits do symbolize fertility due to their prolific breeding and thus, new life. The Catholic Church believes that the Easter Bunny's origins are even older. The ancient Greeks thought that rabbits could reproduce as virgins. In medieval times, the rabbit became associated with the Virgin Mary, symbolizing her virginity.

Eggs have been used throughout history in springtime to celebrate the new season. In Mesopotamia, Christians are said to have dyed eggs after Easter. The tradition was taken up by Orthodox churches and it soon spread throughout Europe, becoming closely associated with Easter celebrations. As eggs were forbidden during Lent, they would be decorated and painted, and eaten on Easter to celebrate the end of the fasting period.

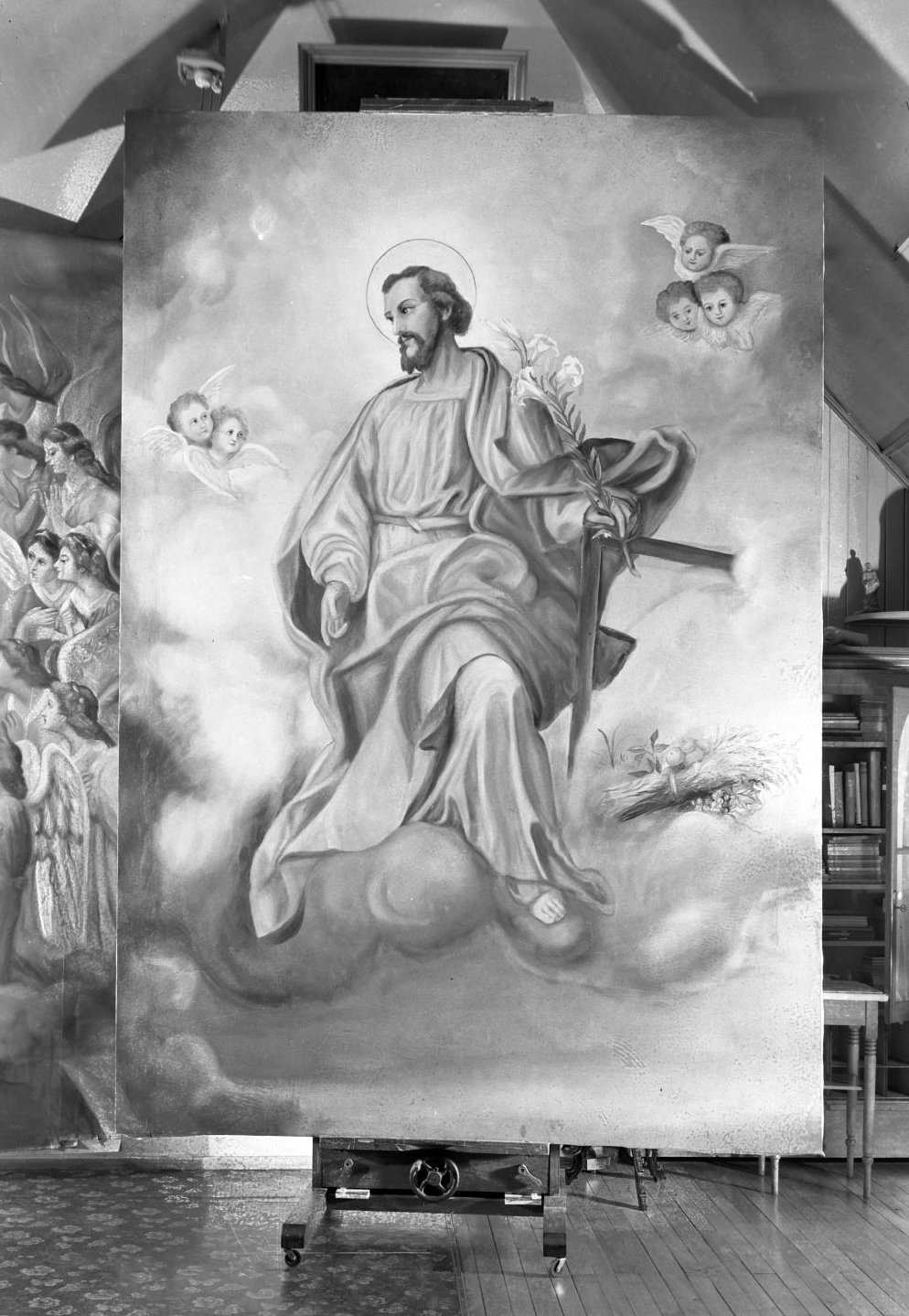

Painting representing "Saint-Joseph with lilies," work of Sister Marie-de-l'Eucharistie (Elmina Lefebvre). Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Lilies are also closely associated with Easter, symbolizing the purity of Christ and rebirth. According to legend, lilies sprung up in the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus went to pray the night before his crucifixion. Native to Taiwan and Japan, lilies were brought to England in the late 18th century. By the 20th century, they had made their way to North America to become the unofficial flower of Easter.

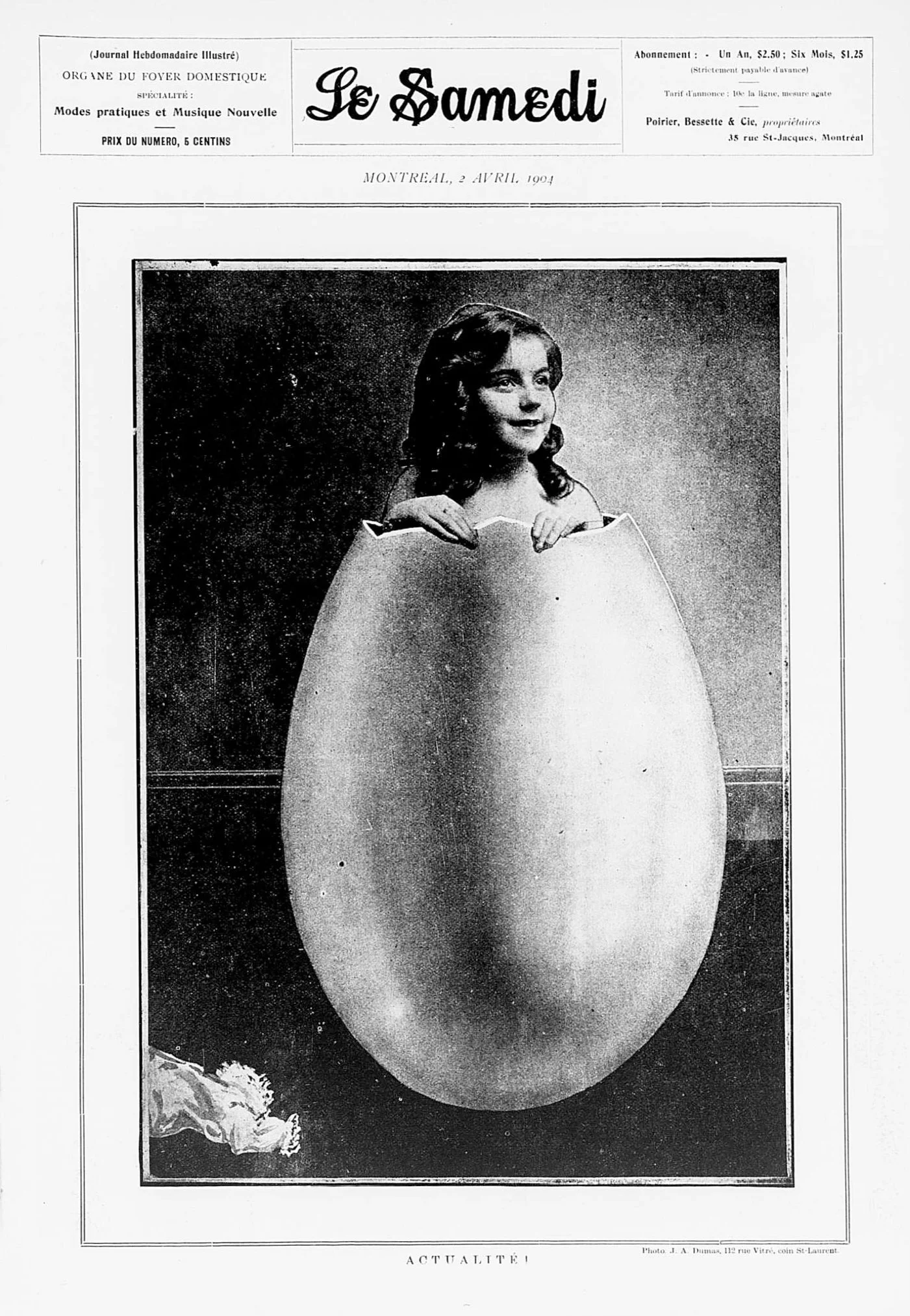

Easter Edition of Le Samedi, April 1904. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Easter postcard featuring two girls in white tops with peaked hoods and knee-length pants, holding a lantern. Postmarked April 22, 1905. Toronto Public Library.

Illustration in the newspaper Le Soleil, March 29, 1902. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Bérangère Landry, "Vous prenez t’y des mi-carêmes," 2001, Cap-aux-Diamants, (64), 20–25. Digitized by Érudit (https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/8385ac).

Philippe Fournier, La Nouvelle-France au fil des édits (Septentrion, Québec : 2011), 116.

Laura Neilson Bonikowsky, "Easter in Canada," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada. Article published 4 Feb 2013; last edited 1 Feb 2017. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/easter-in-canada. Bonikowsky,

Anne-Marie Desdouits, "Au rythme des fêtes et des saisons," Entre sainteté et superstitions no 26, summer 1991. Digitized by Érudit. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/cd/1991-n26-cd1043582/7855ac.pdf.

Pierre Lahoud, "Se fêter," Continuité no 127 (2010), pages 28–31. Digitized by Érudit. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/continuite/2010-n127-continuite1508106/62623ac/

Barbara Le Blanc, "Se masquer à la mi-carême : perspectives de renouveaux communautaires," 2008, Port Acadie, (13-14-15), 335–342. Digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/038438ar).

About Catholics, "Lent in the Catholic Church" (https://www.aboutcatholics.com/beliefs/lent-in-the-catholic-church/).

Le Réseau de diffusion des archives du Québec, "De coutume en culture" (http://rdaq.banq.qc.ca/expositions_virtuelles/coutumes_culture/avril/paques/coutume_culture.html).

History.com, "Easter Symbols and Traditions" (https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/easter-symbols), published 27 Oct 2009, last updated 24 Mar 2021.